Discounting Lost Profits to Present Value

Ex ante, Ex post, and Hybrid Methodologies

January 2019 will be the twentieth anniversary of one of the seminal articles written on discounting lost profits, Peter Schulman’s Economic Damages: Discounting Concepts and Alternatives. This article addresses the concepts and complexities of discounting lost profits that were discussed in the Schulman article and advances and additional methodology for discounting lost profits.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]Resources:

Taking a Deeper Dive into the Lost Profits “But-For” World

Special Considerations for Lost Profits Calculations

Advanced Concepts in Lost Profits Calculations

The Ins and Outs of Present Value Calculations Review of the Three Commonly Accepted Methods

[/su_pullquote]

January 2019 will be the twentieth anniversary of one of the seminal articles written on discounting lost profits, Peter Schulman’s Economic Damages: Discounting Concepts and Alternatives.[1] This article addresses the concepts and complexities of discounting lost profits that were discussed in the Schulman article and advances and additional methodology for discounting lost profits.

Mr. Schulman began his article with these thoughts, “In computing damages based on lost profits, lost future profits should be discounted to present value. Although the basic concept of discounting is simple, in actual practice, discounting is a ‘math problem,’ rather than a ‘word problem,’ which many lawyers and, indeed, many experts do not understand. When practitioners get past the concepts and begin grappling with the computations, they may discover that discounting is a complex process that poses alternatives which often produce widely divergent results.”[2]

Mr. Schulman’s primary focus was the competing issues of whether to use ex ante or ex post discounting when valuing lost profits. While not taking sides on this issue, his article’s explanation of the differences has been often quoted as one of the clearest and most concise discussion on this issue. In the following sections, we will revisit Schulman’s article, highlight court rulings on this issue, and discuss an additional methodology which has become a topic for discussion and disagreement since Schulman’s publication.

Defining ex ante and ex post

The simple Latin to English translation for ex ante and ex post is “from before” and “from after,” respectively.[3] The Webster Dictionary provides a more detailed meaning. Ex ante is defined as, “based on assumption and prediction and being essentially subjective and estimative.” ex post is defined as, “based on knowledge and retrospection and being essentially objective and factual.”[4]

For the issues discussed by Schulman, ex ante and ex post related to the date for discounting. The question was whether damages were to be discounted ex ante, that is to the date of breach (wrong doing), or ex post, that is to the date of judgement (trial).

Pros and Cons for ex ante and ex post

Schulman noted proponents for ex ante discounting argue, “Lost future profits are those that presumably would have been earned by the plaintiff after the date of breach or other injury. Lost future profits should be discounted as of the date of breach to take into consideration, among other things, the risk that the plaintiff could have earned less than the estimated pecuniary losses. In fact, in many cases, the plaintiff could have earned substantially less.”[5] [6]

The argument against ex ante relates to the inability to make the plaintiff whole, if it is decided the plaintiff was injured by the defendant. “The overriding concept in litigation is that the plaintiff must make itself whole by investing its discounted award at a rate of return equal to the discount rate, thereby replacing its pecuniary losses. A plaintiff can replace its pecuniary losses by investing its discounted award from the date the award is received. It is impossible for a plaintiff to recover the pecuniary losses if damages are discounted to the date of breach, because the plaintiff cannot go back in time and invest the award between the date of breach and the date of trial or recovery.”[7]

Schulman reports the supporters for ex post discounting state, “In theory, ex post damages permit the plaintiff to ‘make itself whole’ by investing the discounted lost future profits (those projected after the date of trial) at a rate of return presumed to be equal to the discount rate, thereby replacing the pecuniary losses. In fact, proponents of ex post damages would argue that ex post discounting is a conservative method and militates to the defendant’s benefit because the date of trial is assumed to the date of recovery, which is never the case. As a result, even if the plaintiff invests the discounted award at a rate of return equal to the discount rate, it will receive less than its pecuniary losses.”[8]

Opponents of using the ex post methodology argue by not discounting the losses to the date of breach, the plaintiff will be over compensated. “Undiscounted damages are based on estimates of what would have happened ‘but-for’ the defendant’s alleged wrongful conduct. Such computations are, at best, rough estimates, and the plaintiff could have earned less than the estimated undiscounted damages. Discounting the entire amount of damages rather than a portion following the trial date takes into consideration the risk that the plaintiff’s actual losses could be less than the estimated losses. To award a plaintiff an undiscounted award for the estimated losses between the date of injury and the date of trial would be unjust enrichment to the plaintiff and unfair to the defendant.”[9]

In the end, it is the court that will decide if the methodology used is appropriate for a specific case. It appears many courts have relied on the concept of the Wrongdoer’s Rule for assessing arguments over which method should be used. This rule gives benefit of the doubt to plaintiff, leaving the defendant with the burden of explaining why the methodology used is inappropriate.

“In cases of ex ante and ex post, the courts can use the Wrongdoer’s Rule in siding with the plaintiff’s measure of damages. Because both approaches yield arguably reasonable results, defendants carry the burden of showing why the plaintiff’s analysis is not appropriate for a specific case. This approach is especially relevant when the defendant’s own acts have precluded an accurate understanding of the but-for world (e.g., cases of antitrust and breach of contact).”[10]

Examples of ex ante and ex post

The difference in these two concepts is perhaps best demonstrated by “running the numbers.”

Assume Company A and Company B have a contract in which Company A is to provide services to Company B for a ten-year period. Before the contract begins, Company B breaches the contract and Company A sues for damages. Based on a review of the contract, the estimated revenue Company A was to generate, and the anticipated expenses that would have incurred to generate those revenues, it is determined Company A would have generated profits of $10,000 per year. Further, assume that due to Company A’s efforts it will be able to partially mitigate (offset) its loss for the last five years of the loss period. It is projected Company A’s annual lost profits over the final five years of the lost period will be $5,000 per year. Finally, assume the trial for this litigation will take place at the start of year six in the loss period. This means there are five years of losses estimated prior to the date of trial and five years of losses projected after the date of trial.

For this example, the loss figures have been kept very straight forward. No growth factor has been included. No adjustment for changes in annual costs, up or down, have been considered. These calculations are merely to provide a simple example of the differences in ex ante and ex post calculations.

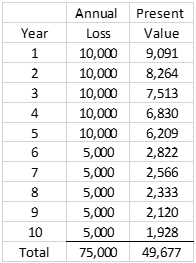

Should an expert choose the ex ante methodology, the ten-year lost profits would be discounted to the date of the breach. This would show ten years of discounting. For this example, a 10% discount rate has been assumed. The resulting lost profits figure is $49,677.

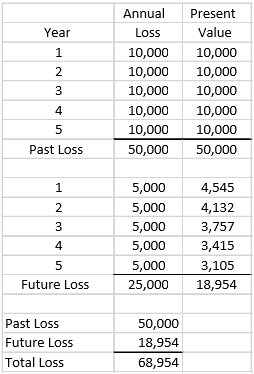

Should an expert choose the ex post methodology, the final five years of the loss period would be discounted to the date of trial. Therefore, the five years of loss between the date of breach and the date of trial would not be discounted and the five years after the date of trial to the end of the loss period would be. Again, a 10% discount rate has been assumed for this example. The resulting lost profits figure is $68,954.

This is a 28% difference in lost profit results between the ex ante and ex post calculations.

Harmonizing these two methodologies is virtually impossible. “The mathematics underlying time value of money concepts make it difficult, and, perhaps, impossible to reconcile the conflicting arguments in support of and against ex ante and ex post damages because the time between the date of breach and date of recovery is lost forever. In other words, a plaintiff cannot invest its recovery until it is received, which is frequently after all or a portion of the loss has been sustained.”[11]

Schulman’s conclusion is a reminder to experts that our calculations are estimates and cannot be sum certain. We calculate a loss based on something that did not happen and assume payment will be made to the injured party on a date when the funds will not be received.

Reality vs. Theory

A review of financial litigation literature shows ex post is the most commonly used methodology. In its review of state and federal cases, Robert Dunn’s Recovery of Damages for Lost Profits reports, “Only one case appears to have discounted future lost profits ex ante, to the date of breach of contract.”[12]

In the oft quoted Energy Capital Corp case, the Court of Appeals stated, “Almost all of Energy Capital’s lost profits would have been earned after the date of judgement. [cite omitted] Accordingly, we hold that the trial court did not err in discounting Energy Capital’s lost profits to the date of judgement instead of the date of breach.”[13]

This does not mean ex ante cannot be used when discounting lost profits. It merely shows the ex post method is the most commonly used methodology and the one most often seen by the courts.

A Hybrid Methodology

Since Schulman’s article, a third option has been discussed in financial literature. This third methodology is a hybrid approach which encompasses a combination of the ex ante and ex post methodologies.

In the Franconia Associates case, the court applied a 14% discount rate to the post judgement lost profits when discounting them back to the date of judgement. Pre-judgement, post breach lost profits were discounted to the date of breach at nine percent. The court said the nine percent discount rate reflected the risk component in the 14% discount rate.[14] [15]

This court appeared to be following the concept discussed by the Court of Appeals in the Energy Capital case. “When calculating the value of an anticipated cash flow pursuant to the DCF [discounted cash flow] method, the discount rate performs two functions: (i) it accounts for the time value of money; and (ii) it adjusts the value of the cash flow stream to account for risk.”[16]

The Franconia Associates court appears to have included both elements (time value of money and risk) when discounting future losses to the date of judgment (ex post) but included only the risk element when discounting past losses back to the date of breach (ex ante).

The adjustment in these discount rates for the time value of money is consistent with financial theory and allows for both the ex ante and ex post methodology to be considered. Losses from the date of trial (judgement) through the end of the loss period are future losses. These losses need to be discounted by a rate that includes the time value of money and appropriate risk factors. Losses from the date of breach through the date of trial are past losses (losses incurred prior to the date of trial). There is no need to include the time value of money because the losses have already occurred. However, the risk for generating those lost profits still existed when the losses were incurred. Therefore, the risk factors and the discount rate they create could still be considered when determining the value of these past losses.

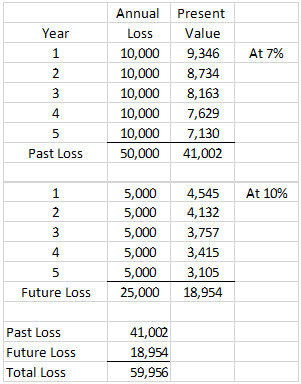

The example used earlier in this article showed the differing results from applying ex ante or ex post when calculating lost profits. Using the same assumptions and discount rate, this hybrid methodology is considered. The only additional assumption to be added is the risk-free rate (time value of money) of three percent. This means the assumed risk factor is seven percent. That rate has been used to discount the pre-judgement, post breach lost profits to the date of breach. The resulting lost profits figure is $59,956.

As expected, this loss figure falls between the ex ante and ex post loss figures, slightly closer to the ex post results.

Time Value of Money and Risk Factors

Although ex ante and ex post methodologies call for the determination of a discount rate, the introduction of the hybrid methodology requires an expert to turn from when to begin discounting to address the time value of money and risk adjustments affecting the discount rate. Ultimately, it will be the time value of money factor that will be the difference between the hybrid past loss discount rate and the future loss discount rate.

The issue of the time value of money and risk adjustment has been discussed by this author in a prior QuickRead article. That article noted commercial damages literature discussing three methods for determining the appropriate discount rate: safe rate of return, rate of return from investing the award, and rate of return commensurate with the risk in receiving the lost profits.

“Most commonly, experts determine a discount rate that is commensurate to the risk that would have been assumed by the injured company to achieve the future lost profits. The greater the risk relating to the company achieving the projected profits, under normal circumstances, the greater the discount rate. Many experts use a Build-up Method for determining this discount rate. The build-up begins with a risk-free rate and adds various risk premiums that, when totaled, provide the discount rate. These risk premiums may include market risk, financial risk, sales risk, product risk, and many others.”[17]

Using the Build-up method would be beneficial when utilizing the hybrid methodology. The article defines the time value of money as the risk-free rate. It recommends using the yield on U.S. Treasury securities maturing at the end of the recovery (loss) period as the risk-free rate to be applied. This risk-free rate becomes the time value of money component to which risk factors are added.

If the build-up approach has been used, the full discount rate may then be used to discount future lost profits to the date of trial (judgement). The same build-up rate less the risk-free rate can then be used to discount post breach, pre-judgement losses back to the date of breach.

The Book of Wisdom

For a business valuation, information known after the date of valuation is generally not considered. This is because it is assumed the willing buyer and willing seller would have made their decisions in arriving at the fair market value for the business based on the information available through the date of sale (or in a litigious situation through the date of wrongful act). For calculating lost profits, an expert is expected to apply facts that occur after the date of breach.

This use of hindsight in assessing lost profits was addressed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1933. “[A]t times the only evidence available may be that supplied by testimony of experts as to the state of the art, the character of the improvement, and the probable increase of efficiency or savings of expense… This will generally be the case if the trial follows quickly after the issue of a patent. But a different situation is presented if years have gone by before the evidence is offered. Experience is then available to correct uncertain prophecy. Here is a book of wisdom that courts may not neglect. We find no rule of law that sets a clasp upon its pages, and forbids us to look within.”[18]

Courts have gone on to express that relying on these post breach events lessens speculation and brings into better focus the initial elements of the loss claim.[19] These post breach changes may be negative or positive. They may provide a better opportunity for generating a profit than had been anticipated at the time of the alleged wrongful act or less. It is this post breach knowledge that the courts expect an expert to use in assessing and refining the lost profit estimates.

An expert may use this post breach information to model the projected lost profits or adjust accordingly the risk factor in the discount rate. By modeling the projected income stream and the subsequent losses, the expert may assume a lesser risk factor due to the adjustments for post breach events. On the other hand, the expert may increase the risk factor for changes in competition, market or economic conditions. Or, the risk factor may be decreased due to changes in competition, market or economic conditions.

The use of the post breach Book of Wisdom should assist an expert in bringing into focus the lost profits analysis. Post breach information may be used in determining the discount rate for ex ante use. However, it is this knowledge that has allowed most experts to argue against discounting lost profits that are post breach pre date of trial and discount only future (post date of trial) lost profits. This is the application of the ex post methodology.

Conclusion

The calculation of lost profits is a complicated process in which many factors must be considered. One of those is the methodology to be used for discounting future lost profits. The most commonly discussed methodologies are ex ante and ex post. Although a discussion of both may be found throughout financial literature, only the ex post methodology is commonly used by financial forensic experts.

Recently, a hybrid methodology has gathered support as a means of addressing perceived short comings in the ex ante and ex post methodologies. The hybrid approach, while theoretically sound, creates additional burdens on the expert. Explaining two discount rates to the jury, the use of two discount periods, and having to relate one to the other are only some of the additional topics that will have to be addressed in both direct and cross examination trial testimony.

Whichever methodology chosen, an expert must be prepared to explain its use, first to the hiring attorney and then to the trier-of-fact. The expert must be ready to discuss the reasoning for the choice and why this methodology best fits the facts of this case.

Change is difficult for most people. Attorneys and judges are no different. For those experts wanting to use the hybrid methodology, be prepared for some “push back” and skepticism for its use. However, as in most situations, it will be the expert who understands the “ins and outs” of the methodology being used and how it applies to the case at hand that will be able to use, defend, and be successful with whichever methodology is chosen.

[1] The Colorado Lawyer / January 1999/ Vol. 28, No. 1 / 41–46.

[2] Schulman, 41.

[3] Latin to English, Google Translator.

[4] Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary.

[5] Schulman, 44.

[6] A portion of the argument between ex ante and ex post is the application of pre-judgement interest that would be awarded to the plaintiff as a result of a favorable verdict. Some jurisdictions allow for an expert to calculate pre-judgement interest, others do not. As an example, in Texas, the pre-judgement interest rate is set by the legislature and calculated by the judge. Experts are precluded from providing a pre-judgement interest calculation to the trier-of-fact. Because of the differences in jurisdictions, the issue regarding pre-judgement interest has not been included in this article.

[7] Schulman, 45.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Litigation Services Handbook, The Role of the Financial Expert, 5th Ed., Roman Weil, Daniel Lentz, David Hoffman, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2012, 5.14.

[11] Schulman, 46.

[12] Recovery of Damages for Lost Profits, 6th Ed., Supplemental September 2018, Supplemental Editors, Sharon Rutberg, Wendy J. Malkin, 318.

[13] Energy Capital Corp. v. United States, 302 F.3d 1314, 1330 (Fed. Cir. 2002).

[14] Recovery of Damages for Lost Profits, 6th Ed., Supplemental September 2018, 318.

[15] Franconia Associates v. United States, 61 Fed. Cl. 718 (2004).

[16] Energy Capital Corp., 1333.

[17] The Present Value of Future Lost Profits, and the Time Value of Money, Allyn Needham, QuickRead, 12/15/2016, 4, https://quickreadbuzz.com/2015/12/16/discount-rates/

[18] Sinclair Ref. Co. v Jenkins Petroleum Co., 289 U.S. 689, 698-99, 53 S. Ct. 736, 77 L. Ed. 1449 (1933).

[19] Litigation Services Handbook, The Role of the Financial Expert, 5th Ed., Roman Weil, Daniel Lentz, David Hoffman, John Wiley& Sons, Inc., 2012, 5.11-5.13.

Allyn Needham, PhD, CEA, is a partner at Shipp Needham Economic Analysis, LLC, a Fort Worth-based litigation support consulting expert services and economic research firm. Prior to joining Shipp Needham Economic Analysis, he was in the banking, finance, and insurance industries for over twenty years. As an expert, he has testified on various matters relating to commercial damages, personal damages, business bankruptcy, and business valuation. Dr. Needham has published articles in the area of financial and forensic economics and provided continuing education presentations at professional economic, vocational rehabilitation, and bar association meetings.

Dr. Needham can be contacted at (817) 348-0213, or by e-mail to aneedham@shippneedham.com.