The Z-Score Revisited

Uses of the Z-score in litigation and insolvency matters

Dr. Edward Altman’s Z-score turned 45 years old this month. For the operations-focused valuation analyst, the Z-score is just as relevant today as it was when Dr. Altman introduced it in September 1968. The key to its enduring success is that it is based on fundamental financial ratios that represent value drivers, even in today’s changing market.

Z-Score

One of the most useful financial and managerial tools available to consultants is the Z-score, a formulation of key financial ratios first presented in the Journal of Finance by Dr. Edward Altman (Altman) in September 1968. The specific purpose of the Z-score was to develop a set of traditional financial ratios that could be used together as an assessment technique to investigate corporate performance in context with bankruptcy prediction. Forty-five years later, Altman’s original multiple discriminant model is still being used and has evolved from its original public manufacturing company model into two revised versions for private firm analysis (manufacturing and non-manufacturing) and onto an advanced model referred to as Altman’s Zeta factor. In fact, during the same period, analysts and consultants have found other uses for the Z-Score. It is those uses and the information provided by the ratios and model that should be of interest to valuation analysts and clients.

Overview

Any valuation analyst unfamiliar with the Z-score should take the time to personally research and review its history and development. For the purpose of this article, it’s sufficient to say that the model consists of a summation of either four or five financial ratios that are assigned different weighting that results in a value for performance interpretation and prediction of financial distress. The common financial ratios and factors include working capital/total assets (X1), retained earnings/total assets (X2), earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT)/total assets (X3), equity/book value of total debt (X4), and sales/total assets (X5). There is nothing new about these ratios except what the valuation analyst can do with them in concert, and as a diagnostic tool.

Z-score Application and Care

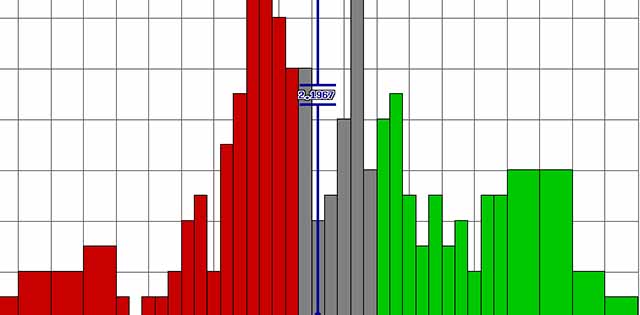

The first and most obvious use of Altman’s Z-score by valuation analysts is certainly in the area of financial benchmarking. A meaningful financial analysis requires the valuation analyst to compare and assess a subject company’s financial performance and condition against some benchmark(s) or composite peer group. A subject company Z-score should validate an analyst’s assessment of where the company rates within its peer group. For those using RMA and its valuation edition, the analyst can further compare Z-scores between the subject and composite peer group. Taken a step further, the valuator can break the analysis down by quartile and note the subject company’s relative position within the composite. I would suggest that this approach would serve to bolster any conclusion or opinion the analyst might draw from use of the direct market data method, should that valuation method be considered in the valuation engagement.

As useful as the Z-score model may be as part of the valuation analyst’s financial analysis and ratio measurement, a certain amount of caution and common sense must be exercised. First, like other financial ratios, the Z-score is constructed and dependent upon accounting data, which is subject to different reporting conventions, objectives, accuracy, and manipulation. Based upon the analysis and engagement specifics, the valuation analyst must determine whether to use reported financial data or normalized financial data or both in the application of the Z-score model. Valuation of professionally managed firms that mirror the operation, reporting, and controls of public companies do not present a problem in the application of the Z-score. It is usually the smaller, more closely-held firms, and minority interest valuations that create the challenge in application of the model.

A second use of the Z-score by the valuation analyst is in support of valuation approach and method. In valuation, there are two fundamental premises of value—going concern and as in liquidation. The value of a subject company is supposed to be the higher of the two values determined under the two premises. This approach is advanced through the appraisal concept of highest and best use, which requires the valuation analyst to consider the optimal use of the assets being appraised under current market conditions. If a business will command a higher price as a going concern, then it should be valued as such. Conversely, if it will command a higher price if liquidated, then it should be valued “as if in orderly liquidation.”

As previously discussed, care must be exercised with the accounting and financial data used in the Z-score model. Before using the Z-score to support a “as in liquidation” premise, the valuation analyst needs to understand the nature and limitations of the model. In effect, the valuator is applying the acid test with the model when predicting the likelihood of financial distress and possible bankruptcy.

The weakness of the model is that it is static in nature, meaning that it measures a single point in time. The model weakness, as discussed in other research papers by Tyler Shumway in 1999, Sudheer Chava and Robert Jarrow in 2004, and later by Dr. Altman, is basically the difference between a static model and dynamic model and is beyond the point of this writing. To address and overcome the inherent weakness of the Z-score model, the valuation analyst must consider multiple period testing to prove and support financial distress or an existing trend. That should not come as a surprise as independent credit organizations, such as the Credit Research Foundation, include multiple period tests of the Z-score in their credit model, as well as for the DuPont Model. In two litigation related valuations, I found myself at odds with the opposing expert over the premise of value and valuation approach. In those two engagements, I provided the solution and support by multi-period testing at dates other than year end. As a valuation analyst and model advocate, I have no issues with the Z-score as predictor of financial distress as long as multiple periods are considered.

A final use of the Z-score model is corporate turnaround. This application may be of limited use to most valuation analysts. However, for those in practice management or offering operational consulting as an adjunct service, it is an extremely effective diagnostic and management tool. Note the word diagnostic. I used the Z-score model in every corporate turnaround project that I managed. It’s simply treatment and reversal of corporate decline by the numbers. From a financial perspective, the consultant addresses the four or five ratios with whatever operational changes, processes, controls, and systems he or she deems necessary. The consultant then uses the model to assess financial and operational progress through interval (multi-period) testing. From a personal perspective, I like to test the Z-score on a bi-weekly and monthly basis and incorporate it into a rolling 13-week forecast. The Z-score is not an end-all corporate turnaround tool, but it does represent a valuable and credible diagnostic aid for the turnaround and restructuring consultant. If this is not convincing enough, one can be sure that creditors and credit bureaus are running the Z-score on any company financial statements made available.

Summary

Dr. Edward Altman’s Z-score turned 45 years old this month. For the operations-focused valuation analyst, the Z-score is just as relevant today as it was when Dr. Altman introduced it in September 1968. The key to its enduring success is that it is based on fundamental financial ratios that represent value drivers even in today’s changing market.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://m.c.lnkd.licdn.com/mpr/mpr/shrink_200_200/p/1/000/01a/3ed/2456370.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Jeff Harwell, CVA, MAFF, CMEA, is principal of Harwell & Company, a Dallas/Fort Worth-area valuation analyst, economic damage, and litigation support firm. Mr. Harwell received his BBA. from the University of Texas at Arlington and his MBA from the Neeley School at Texas Christian University. He currently serves on the National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA) Standards Committee, as well as NACVA’s State Chapter Committee. Mr. Harwell’s clients include attorneys, business owners, and CPAs. Mr. Harwell can be reached at jharwell@bfval.com[/author_info] [/author]