Valuing Stand-Alone Ancillary Service and Technical Component (ASTC) Enterprises under Hypothetical Conditions

In this article, Robert Cimasi and Matthew Wagner provide a roadmap of the valuation and legal issues valuation professionals confront valuing a medical practice that also provides ancillary and technical component (ASTC) services. The fact that the ASTC services are often integrated with the professional services of a practice does not restrict the ASTC service line from having value separate and aside from that of the practice enterprise. The authors share their views on how to value the hypothetical ‚Äúcarve-out‚ÄĚ ASTC, including what approaches to consider.

Fair market value engagements of business enterprises that are developed in accordance with professional valuation standards, e.g., The Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP),[1] require concise statements as to the assumptions utilized regarding the hypothetical transaction environment that is implicit in the definitional requirements of fair market value, and which impacts on the value of an ownership interest in the subject property.¬† These statements include the standard of value (in this case, fair market value), which answers the question, ‚ÄúValue to whom?‚ÄĚ as well as the premise of value, which further clarifies the facts and circumstances of the transaction conditions to be considered for the engagement.¬† However, under certain facts and circumstances, aspects of the transaction may arise that require the valuation analyst to utilize a hypothetical condition, (as allowed by professional valuation standards), in determining the highest and best use of the subject property interest.¬† The highest and best use ‚Äú‚Ķis that use among possible alternatives which is legally permissible, socially acceptable, physically possible, and financially feasible, resulting in the highest economic return.‚ÄĚ[2]

Fair market value engagements of business enterprises that are developed in accordance with professional valuation standards, e.g., The Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP),[1] require concise statements as to the assumptions utilized regarding the hypothetical transaction environment that is implicit in the definitional requirements of fair market value, and which impacts on the value of an ownership interest in the subject property.¬† These statements include the standard of value (in this case, fair market value), which answers the question, ‚ÄúValue to whom?‚ÄĚ as well as the premise of value, which further clarifies the facts and circumstances of the transaction conditions to be considered for the engagement.¬† However, under certain facts and circumstances, aspects of the transaction may arise that require the valuation analyst to utilize a hypothetical condition, (as allowed by professional valuation standards), in determining the highest and best use of the subject property interest.¬† The highest and best use ‚Äú‚Ķis that use among possible alternatives which is legally permissible, socially acceptable, physically possible, and financially feasible, resulting in the highest economic return.‚ÄĚ[2]

USPAP defines a hypothetical condition as ‚Äú‚Ķa condition, directly related to a specific assignment, which is contrary to what is known by the appraiser to exist on the effective date of the assignment results, but is used for the purpose of the analysis.‚ÄĚ[3] ‚ÄúHypothetical conditions are contrary to known facts about physical, legal, or economic characteristics of the subject property; or about conditions external to the property, such as market conditions or trends; or about the integrity of data used in an analysis.‚ÄĚ [4],[5]

The use of a hypothetical condition, under the concept of the highest and best use, is illustrated below, using the example of the determination of fair market value of a cardiology physician practice that has an in-office diagnostic imaging ancillary service line.

The standard of value most often utilized in performing healthcare valuation engagements is that of fair market value, which has a distinct and separate meaning in healthcare, in contrast to its definition in the context of valuation in other industries.

The standard of fair market value is defined as the most probable price that the subject interest should bring if exposed for sale on the open market, but exclusive of any element of value arising from the accomplishment or expectation of the sale.  This standard of value assumes an anticipated hypothetical transaction, in which the buyer and seller are each acting prudently with a reasonable equivalence of knowledge, and that the price is not affected by any undue stimulus or coercion.[6]

Implicit in this definition are the following further assumptions:

- The hypothetical transaction contemplates a universe of typical potential purchasers for the subject property and not a specific purchaser or specific class of purchaser;[7]

- Buyer and seller are typically motivated;[8]

- Both parties are well informed and acting in their respective rational economic self-interests;[9]

- Both parties are professionally advised and the hypothetical transaction is assumed to be closed with the typical legal protections in place to safeguard the transfer of ownership of the legal bundle of rights which define and encompass the transacted property or interest; [10]

- A sufficiently reasonable amount of time is allowed for exposure in the open market; [11]

- A reasonable availability of transactional capital in the marketplace;[12] and,

- Payment is made in cash or its equivalent. [13]

For purposes of healthcare valuation, the definition of the standard of fair market value is both supplemented and further restricted by regulatory edicts, e.g.:

-  The Anti-Kickback Statute, which requires the payment of:…fair market value in arms-length transactions…[and that any compensation is] not determined in a manner that takes into account the volume or value of any referrals or business otherwise generated between the parties for which payment may be made in whole or in part under Medicare, Medicaid or other Federal health care programs.[14] [emphasis added]

- The Stark Law, and accompanying regulations, which provide definitional guidance related to fair market value, including the following:The anticipated hypothetical transaction would be conducted in compliance with ‚ÄúStark I & II‚ÄĚ legislation, prohibiting physicians from making referrals for ‚Äúdesignated health services‚ÄĚ reimbursable under Medicare, to an enterprise with which the referring physician has a financial relationship.[15]¬† ‚ÄúStark II‚ÄĚ defines ‚Äúfair market value‚ÄĚ as ‚Äúthe value in arm‚Äôs length transactions, consistent with the general market value‚Ķ‚ÄĚ[16]

- The Internal Revenue Code (IRC) and accompanying Treasury Regulations, IRS revenue rulings, and other IRS pronouncements, which provide guidance pertaining to determining fair market value for transactions involving tax-exempt organizations, e.g.:the general rule for the valuation of property, including the right to use property, is fair market value (i.e., the price at which property or the right to use property would change hands between a willing buyer and willing seller, neither being under any compulsion to buy, sell or transfer property or the right to use property, and both having reasonable knowledge of relevant facts).[17]

In addition to the threshold of fair market value, transactions in the healthcare industry are also scrutinized as to whether they meet the regulatory threshold referred to as commercial reasonableness.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has interpreted the term ‚Äúcommercially reasonable‚ÄĚ to mean that an arrangement appears to be:

…a sensible, prudent business agreement, from the perspective of the particular parties involved, even in the absence of any potential referrals[18]

The Stark II, Phase II commentary also notes that:

An arrangement will be considered ‚Äėcommercially reasonable‚Äô in the absence of referrals if the arrangement would make commercial sense if entered into by a reasonable entity of similar type and size and a reasonable physician of similar scope and specialty, even if there were no potential DHS referrals.[19]

Additionally, commentary published by the 2006 American Law Institute suggests that:

Each financial and contractual connection between hospitals and physicians should be scrutinized to ensure that goods or services changing hands are being provided at fair market value, and at a level no more than necessary for the business purposes of the arrangement.[20]

While the standard of value for healthcare related valuation engagements is typically set forth by legal and regulatory edicts, determining the premise of value for an engagement should be based on the most probable transactional facts and circumstances for the subject property interest within the context of the current transactional marketplace as of the valuation date.  For example, when valuing a physician practice, once adjustments are made to reflect the economic operating expense burden related to the fair market value physician compensation necessary to support the forecasted productivity and revenue stream, there is often insufficient net cash flow to support the value of the invested capital of the enterprise in its entirety.  This results in no economic return to capitalize into enterprise value.

In those instances, the highest and best use of the assets of the practice enterprise may not be reflected in a transaction utilizing the typically employed premise of value in use as a going concern, but rather, might more appropriately be reflected under the premise of value-in-exchange, i.e.: (1) as an orderly disposition of an assemblage of assets; (2) as an orderly disposition of assets, without assemblage; or, (3) as a forced liquidation.

Dr. Pratt points out that the concept of highest and best use drives a selection of the valuation premise, which may apply under the standard of fair market value:

Each of these alternative premises of value may apply under the same standard, or definition, of value.¬† For example, the fair market value standard calls for a ‚Äėwilling buyer‚Äô and a ‚Äėwilling seller.‚Äô¬† Yet, these willing buyers and sellers have to make an informed economic decision as to how they will transact with each other with regard to the subject business.¬† In other words, is the subject business worth more to the buyer and the seller as a going concern that will continue to operate as such, or as a collection of individual assets to be put to separate uses?¬† In either case, the buyer and seller are still ‚Äėwilling.‚Äô¬† And, in both cases, they have concluded a set of transactional circumstances that will maximize the value of the collective assets of the subject business enterprise.[21] [Emphasis added]

Reilly and Schweihs echo Dr. Pratt’s comments in reference to intangible assets, stating that:

…[t]he selection of the appropriate premise of value may be dictated by the highest and best use of the subject intangible asset.  The highest and best use of an intangible asset is typically defined as the reasonably probable and legal use of the intangible asset that is physically possible, appropriately supported, financially feasible, and results in the highest use.[22] [emphasis added]

Assume the cardiology practice referred to above is being valued, one potential asset of a cardiology practice may be the ancillary services and technical component (ASTC) service line, unit of the practice is comprised of diagnostic imaging tests that are performed by providers of the subject practice, in contrast to the core professional services of the business.  This ASTC service line may be valued as a stand-alone enterprise, under the premise of value in use as a going concern, utilizing a hypothetical condition (as defined below).

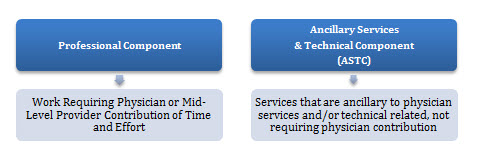

Of note is that there are two general types of services provided by a physician practice: (1) professional services; and, (2) ancillary & technical component services (Figure 1).¬† Professional services are those that require a physician‚Äôs or midlevel provider‚Äôs (MLP) contribution of time and effort.¬† In contrast, ASTC services are services that do not require a professional provider‚Äôs work input, but which may, nevertheless, be performed by the physician, MLP, or a staff technician, e.g., performing the technical aspect of diagnostic imaging tests.¬† These services are referred to as ‚Äútechnical‚ÄĚ because they are technologically intensive in nature, and the provision of these ASTC services may require significant capital equipment and an appropriately trained technical staff.¬† ASTC services are referred to as ‚Äúancillary‚ÄĚ because they are not directly related to the provision of professional services, but can assist in the provision of those services. [23]

Figure 1: Types of Services Provided by Physician Practices

The fact that the ASTC services are often integrated with the professional services of a practice does not restrict the ASTC service line from having value separate and aside from that of the practice enterprise within which it is apart.  The transactional marketplace provides many examples of service lines, or business units, within large corporations that are commonly valued separately and sold as though they were independent, stand-alone entities.  However, in healthcare, the appraisal of a service line that is integrated into a physician practice needs to address two controlling issues:  (1) under professional valuation standards, the disclosure of the use of a hypothetical condition is required to value an existing ASTC service line that is integrated with a physician professional practice, as a hypothetical, stand-alone, enterprise;[24] and (2) significant attention must be paid to ensure that the transaction does not run afoul of the specific regulatory restrictions pertaining to the valuation of healthcare enterprises (as briefly mentioned above, and as further discussed below).

The hypothetical, stand-alone, ASTC enterprise (also referred to as a ‚Äúcarve out‚ÄĚ ASTC enterprise) is typically valued using two approaches, i.e., the Market Approach and the Income Approach.¬† The Market Approach relies on: (1) recent sales of similar ASTC related businesses with homogenous badges of comparability to the subject ASTC enterprise; and/or, (2) guideline publicly traded ASTC related businesses with homogenous badges of comparability to the subject ASTC enterprise, to ascertain an indication of value.

The Income Approach utilizes some form of discounted future net economic benefit generated by the subject ‚Äúcarve out‚ÄĚ ASTC enterprise to derive an indication of value.¬† Note that, the Cost Approach is typically not utilized to value ‚Äúcarve out‚ÄĚ ASTC enterprises, since the purpose of splitting out the ASTC enterprise from the practice in its entirety is premised on the assumption that the ASTC enterprise generates sufficient net cash flow, that when capitalized, produces an indication of value in an amount which is higher than the sum of the individual ASTC-related tangible and intangible assets, indicating that the highest and best use of the ‚Äúcarve out‚ÄĚ ASTC enterprise can be found under the premise of value in use as a going concern, in contrast to the premise of value in exchange, i.e.: (1) as an orderly disposition of an assemblage of assets; (2) as an orderly disposition of assets, without assemblage; or, (3) as a forced liquidation.

When using an Income Approach to value a ‚Äúcarve out‚ÄĚ ASTC enterprise, the net economic benefit related to the ownership of the ASTC enterprise must be isolated from the net economic benefit associated with the ownership of the residual professional practice.¬† This ability to isolate the ASTC enterprise net economic benefit is part of the hypothetical condition relied upon under professional valuation standards, (further discussed below).

Isolation of the net economic benefit to be produced by the subject ‚Äúcarve out‚ÄĚ ASTC enterprise includes the following:

- Identifying the procedures to be included in the ‚Äúcarve out‚ÄĚ ASTC service line;

- Separating out the technical only, ASTC revenue stream generated by the services to be included in the ‚Äúcarve out‚ÄĚ ASTC service line from the revenue stream of the professional enterprise;

- Determining the most probable economic operating expense burden that would be incurred to produce the technical only ASTC revenue stream. For example, the economic operating expense burden related to the trained and assembled workforce utilized exclusively by the ASTC service line (e.g., nuclear technicians, echo technicians, etc.), would be entirely allocated to the ASTC service line.  However, it is likely that many operating costs are shared by both the professional and the ASTC enterprises, making it often difficult and sometimes impossible to appropriately allocate expenses.  In those instances, benchmarking analysis is recommended in order to distinguish the most probable economic operating expense burden to be incurred by the ASTC enterprise in the future; and,

- Determining the most probable economic capital expense burden that would be incurred to produce the technical only ASTC revenue stream. Since much of the tangible personal property (TPP) of a physician practice is utilized by both the ASTC service line and the residual professional practice (e.g., billing computers, desks, etc.), the forecast of capital expenditures (and the corresponding depreciation projections) for the ASTC service line, should include amounts necessary to reflect the most probable level of economic capital expense necessary to support the revenue stream of the ASTC service line, which can be derived from normative industry benchmark survey data.  This is especially the case when the initial allocation of TPP to the ASTC service line includes only those items that are exclusively utilized in the provision of ASTC related services (e.g., nuclear camera, echo machine, etc.).

Once the net economic benefit of the subject ‚Äúcarve out‚ÄĚ ASTC enterprise has been isolated, the final steps in using an Income Approach are: (a) to develop an appropriate risk adjusted required rate of return to apply to that future net economic benefit stream; and, (b) to determine the types and amounts of any further premiums or discounts (e.g., control premiums, discount for lack of marketability, etc.).

In addition to the isolation of the net economic benefit stream, as mentioned above, there are other underlying assumptions that form the foundation of the hypothetical condition, allowed by professional valuation standards to value a ‚Äúcarve out‚ÄĚ ASTC enterprise as a hypothetical, stand-alone business, under the premise of value in use as a going concern.¬† These assumptions include the following:[25]

- The market service area contains sufficient demand for the technical services of the ASTC service line to support the projected, post transaction volume of procedures of the ASTC service line, as an independent operating enterprise;

- There is a sufficient supply of physician manpower within the geographic proximity limitations of the market service area, separate and aside from those that currently own, or those who are currently employed, by the subject practice, to support the technical services of the ASTC service line, post transaction, as an independent operating entity, in a manner that clearly establishes that there is no remuneration based on the volume or value of referrals from the subject practice physicians;

- The revenue stream from which the economic benefit is derived should be quantifiable and separately identifiable from the revenue stream of the professional component of the subject practice;

- An appropriate economic operating expense burden, accurately allocated between the defined services and revenue of the ASTC service line to be appraised and the residual practice revenue streams, as well as an appropriate economic capital expense burden, should be developed to be applied against the revenue stream of the ASTC service line to arrive at the economic benefit of ownership to be capitalized into Fair market value;

- An appropriate risk adjusted required rate of return for the ASTC service line should be developed that reflects the hypothetical nature of the ASTC service line and the uncertainty related to the projected operations of the ASTC service line, which has been converted from a well-established business with a presumably steady referral stream to a more risky venture with less certain referral patterns. This adjustment is typically reflected in the company specific risk premium component of the cost of equity, which is increased to reflect the uncertainty of the projected cash flows in comparison to those reflected in the historical financials or productivity reports, so that the risk adjusted required return on an equity interest in the subject ‚Äúcarve out‚ÄĚ ASTC enterprise (including all other forms of company specific risk) approximates seed-stage, venture capital (VC) required rates of return (which ex-post VC rates recently have been in the range of 22.5%‚Äď45.0%[26]); and,

- The anticipated hypothetical transaction would be conducted in compliance with the Anti-Kickback Statute, making it illegal to knowingly pay or receive any remuneration in return for referrals.[27]

In summary, a hypothetical condition forms the basis of performing certain valuation engagements in conformance with professional valuation standards.  If appropriately applied, these conditions will provide additional guidance regarding the specific facts and circumstances related to the subject property interest to the intended users of the valuation report.  In the healthcare industry, this is particularly useful given the ongoing reform efforts, dynamic transactional arena, and the concentration and ambiguity of regulatory scrutiny on the underlying transactions that form the basis for the valuation engagements.

Robert James Cimasi, MHA, ASA, FRICS, MCBA, CVA, CM&AA, serves as Chief Executive Officer of Health Capital Consultants (HCC), a nationally recognized healthcare financial and economic consulting firm headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri, serving clients in 49 states since 1993. Mr. Cimasi has over 30 years of experience in serving clients, with a professional focus on the financial and economic aspects of healthcare service sector entities including: valuation consulting and capital formation services; healthcare industry transactions including joint ventures, mergers, acquisitions, and divestitures; litigation support & expert testimony; and, certificate-of-need and other regulatory and policy planning consulting. Mr. Cimasi can be reached at (414) 994-7641 or at RCimasi@healthcapital.com.

Matthew J. Wagner, MBA, CFA, is senior vice president of Health Capital Consultants), where he focuses on the areas of valuation and financial analysis. Mr. Wagner has provided valuation services regarding various healthcare related enterprises, assets and services, including, but not limited to, physician practices, acute care service lines, diagnostic imaging service lines, ambulatory surgery centers, long-term care enterprises, provider-owned insurance plans, equity purchase options, physician clinical compensation, and healthcare equipment leases. Mr. Wagner can be reached at (314) 994-7641.

[1]     The Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act of 1989 (FIRREA) authorized the Appraisal Subcommittee (ASC) of the Appraisal Foundation, which is made up of representatives of the leading U.S. government agencies and non-governmental organizations empowered to oversee the U.S. mortgage and banking system, to develop USPAP.  Source : History of the Foundation, The Appraisal Foundation, 2014, https://netforum.avectra.com/eWeb/DynamicPage.aspx?Site=TAF&WebCode=History (Accessed 10/20/2014).

[2] ¬†¬†¬† Rickert, Richard. “The Principles and Concepts of Valuation: Theory of Utility and Value, Value Influences, and Value Concepts.” In Appraisal and Valuation: An Interdisciplinary Approach, 55. Vol. I. Washington, DC: American Society of Appraisers, 1987.

[3] ¬†¬†¬† “Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice, 2014-2015 Edition.” The Appraisal Foundation. Accessed September 18, 2014. http://www.appraisalfoundation.org, 25.

[4]     Comments provide clarification to definitions included in the DEFINITIONS section of USPAP. Ibid.,  U-3.

[5]     Ibid.

[6]     Cimasi, Robert James. Healthcare Valuation: The Financial Appraisal of Enterprises, Assets, and Services. Vol. 2. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2014. 18-19.

[7] ¬†¬†¬† Investment Value may be defined as: ‚Äú‚Ķthe specific value of an investment to a particular investor or class of investors based on individual investment requirements; distinguished from market value, which is impersonal and detached.‚ÄĚ Source¬†: “Investment Value.” In The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal, 152. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Appraisal Institute, 2002.

[8]     Revenue Ruling 59-60, 1959-1 C.B. 237.

[9]     Ibid.

[10] Thomas, Rawley, and Benton E. Gup. The Valuation Handbook: Valuation Techniques from Today’s Top Practioners. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2010. 422.

[11] Ibid.

[12] ¬†¬†¬†“ASA Business Valuation Standards.” American Society of Appraisers. Accessed August 29, 2014. Accessed at http://www.appraisers.org/docs/default-source/discipline_bv/bv-standards.pdf?sfvrsn=0.29.p. 27.

[13] Thomas, Rawley, and Benton E. Gup. The Valuation Handbook: Valuation Techniques from Today’s Top Practioners. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2010. 422

[14] ¬† ‚ÄúExceptions,‚ÄĚ 42 C.F.R. 1001.952(d)(5).

[15]   42 U.S.C.A. §1395nn(a) (2006); Social Security Act §1877(a) (2006).

[16]   42 U.S.C.A. §1395nn(h)(3) (2006); Social Security Act §1877(h)(3) (2006).

[17] ¬† ‚ÄúExcess Benefit Transaction,‚ÄĚ Treasury Regulation ¬ß53.4958-4(b)(i) (2002).

[18] ¬† ‚ÄúMedicare and Medicaid Programs; Physicians‚Äô Referrals to Health Care Entities With Which They Have Financial Relationships,‚ÄĚ 63 Fed Reg. 1700 (Jan. 9, 1998).

[19] ¬† ‚ÄúMedicare Program; Physicians‚Äô Referrals to Health Care Entities With Which They Have Financial Relationships (Phase II),‚ÄĚ 69 Fed. Reg. 16107 (Mar. 26, 2004).

[20]   Martin, Alson R. Healthcare Joint Ventures. American Law Institute., American Law Institute, SM047 ALI-ABA 1093 (2006).

[21]   Pratt, Shannon P. Valuing a Business: The Analysis and Appraisal of Closely Held Companies. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008.48.

[22]   Reilly, Robert, and Robert Schweihs. Valuing Intangible Assets. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1999. 62.

[23]   Cimasi, Robert James. Healthcare Valuation: The Financial Appraisal of Enterprises, Assets, and Services. Vol. 2. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2014. 571-72.

[24]    Ibid., 572.

[25]   Ibid., 572-73.

[26] ¬† Everett, Craig R. “2014 Capital Markets Report.” Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Project, 8. 2014.

[27] ¬† ‚ÄúCriminal Penalties for Acts Involving Federal Health Care Programs,‚ÄĚ 42 U.S.C. ¬ß1320a-7b(b).