Taking a Deeper Look into Momentive, Part 2

Why the Choice Between Prime and Treasury Rate Matters

Many bankruptcy practitioners have focused on the recent decisions in Momentive[1] that forced secured creditors to refinance prepetition loans at below market interest rates. Most of these practitioners’ publications focus on the courts’ findings and the potential implication on future matters. However, three interesting questions are not addressed in most (if any) of these publications.

The first part of this article addressed two questions:

The first part of this article addressed two questions:

- How much economic value was taken from the secured creditors if one believes they should have received the market rate of interest?

- Is there a limit to the amount of implied lender’s costs, profits, and fees that should be removed from the market interest rate when determining the cramdown interest rate?

This second part addresses the third question:

- Could future courts use the same methodology employed in Momentive yet arrive at the market interest rate by making a reasonable change in one or two assumptions?

Determination of the Cramdown Rate in Momentive

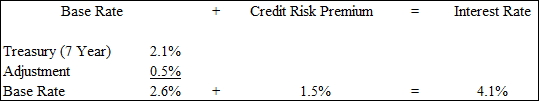

The bankruptcy court arrived at a cramdown rate of approximately 4.1% as of August 26, 2014 for the first lien debt.[2] This interest rate had two components: (1) a base rate of 2.6%, and (2) a credit risk premium of 1.5%. See Figure 1.

Base Rate

The base rate was also comprised of two components: (a) the seven-year treasury rate (which was 2.1% at the time), and (b) an adjustment of 0.5%. According to the bankruptcy judge, the seven-year treasury rate of 2.1% was “materially” lower than the prime rate of 3.25%, which he characterized as “a somewhat anomalous result”. The adjustment of 0.5% was an attempt to bridge the gap between the treasury rate (which includes no credit risk) and the prime rate (which includes some credit risk).[3]

The need to reconcile the seven-year treasury rate with the prime rate arises because the Supreme Court used the prime rate in Till whereas the debtor proposed to use the seven-year treasury rate in Momentive. The debtor in Till was a married couple (the dispute was over the cramdown loan on a used truck). The debtor in Momentive was a large corporation (the dispute was over cramdown loans with a $1.35 billion face value). It made sense to start with the prime rate in Till and the seven-year treasury rate in Momentive.

Credit Risk Premium

The credit risk premium of 1.5% was based on the analysis presented by the debtor. The bankruptcy judge also observed that the 1.5% premium was within the one to three percent range generally used (circa cases thru 2004) according to the plurality’s opinion in Till.

Comparison of Interest Rates

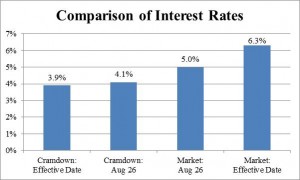

Figure 2 shows the relevant interest rates for the first lien debt. As of August 26 (the date of the bench ruling), the difference between the cramdown rate (4.1%) and the market rate (5.0%) was 90 basis points. As of October 24, 2014 (the “Effective Date” of the debtor’s reorganization plan), the difference between the cramdown rate (approximately 3.9%) and the market rate (approximately 6.3%) was 240 basis points.

The cramdown rate presumably decreased from 4.1% (as of August 26) to 3.9% (as of the Effective Date) due to the decline in the seven-year treasury rate.[4]

The market rate is implied from the valuation performed by the debtor for fresh start accounting purposes. See the first part of this article for further discussion.

Roadmap to Reconcile the Cramdown and Market Rate as of August 26

The cramdown rate needs to be increased by 90 basis ponts (from 4.1% to 5.0%) to reconcile with the market rate as of August 26.

Credit Risk Premium

There is an easy way to increase the cramdown rate by 90 basis points. We can increase the credit risk premium from 150 basis points to 240 basis points and note that the revised credit risk premium is still within the 100 to 300 basis points range referenced in Till. However, we will not do that. The bankruptcy judge believed the 150 basis points credit risk premium was appropriate and we will not second guess that decision, which was based on debtor-specific and credit-specific factors.

Base Rate

Another way to increase the cramdown rate by 90 basis points is to increase the base rate. Recall that the bankruptcy judge made a subjective adjustment by increasing the seven-year treasury rate by 50 basis points. We will consider the possibility that a larger adjustment could/should have been made.

The difference between the prime rate (3.25%) and the seven-year treasury rate (2.10%) was 115 basis points on August 26. The bankruptcy judge essentially split-the-baby when he added 50 (out of 115) basis points to the seven-year treasury rate. If the bankruptcy judge used the full spread of 115 basis points, the cramdown rate would have been 4.75%, which is only 25 basis points away from the market rate of 5.00%.

Why did the bankruptcy judge essentially split-the-baby by only using 50 out of the 115 basis points difference between the prime rate and seven-year treasury rate? He explained that this “material” difference was “somewhat anamolous.”  The implication appears to be that the 115 basis points spread was abnormally high and that a normal spread should be used.

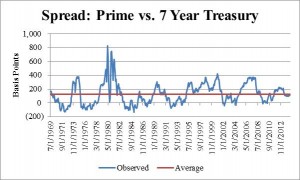

To test the implication the spread between the prime rate and seven-year treasury rate was abnormally high as of August 26, we will examine the historical relationship between the prime rate and seven-year treasury rate. Unfortunately, references to this data are not contained within the Momentive opinions. Thus, we will review data that is available on the Federal Reserve’s website.

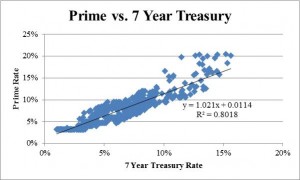

Scatter Plot and Linear Regression

We will start our analysis by reviewing a scatter plot and linear regression that uses all of the relevant data that is available on the Federal Reserve’s website (i.e., 542 monthly observations over a 45-year period).[5] As shown in Figure 3, there is a high correlation (r-squared of 0.80)[6] between the prime rate and seven-year treasury rate. Notably, the y-intercept (the predicted prime rate when the treasury rate is 0%) is 1.14% and there is an upwards slope (the predicted prime rate increases at a greater rate than the increase in the seven-year treasury rate). These observations suggest that the 50 basis points adjustment to the seven-year treasury rate in Momentive was too low. More specifically, the predicted adjustment is 118 basis points, not 50 basis points, when the seven-year treasury rate is 2.1%, which it was on August 26.[7]

Figure 3[8]

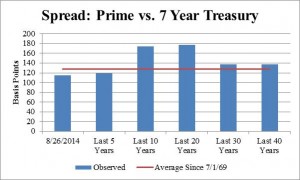

Average Spread

We will next review the historical spread over different time periods. As shown in Figure 4, the 115 basis point spread that existed on August 26 was lower than the historical average of 128 basis points. Thus, a compelling argument could be made for not splitting-the-baby (i.e., take 50 out of the 115 basis points spread) and instead adding to the 115 basis point spread that existed on August 26.

Figure 4[9]

It is now not difficult to arrive at an adjustment to the seven-year treasury rate that results in the (near) market rate. Use of the historical average spread of 128 basis points increases the cramdown rate to 4.88%, which is almost equal to the market rate of 5.00%. The remaining 12 basis points (which requires a 140 basis points increase to the seven-year treasury rate) could be justified because it results in a spread that remains lower than the average spread that prevailed over the preceding 10-year and 20-year periods and is in-line with the average spread that prevailed over the preceding 30-year and 40-year periods.

This result is not surprising because the two approaches (base rate plus a credit risk premium and the market rate) should be reconciable. In fact, the plurality in Till made this exact point when it stated:

if all relevant information about the debtor’s circumstances, the creditor’s circumstances, the nature of the collateral, and the market for comparable loans were equally available to both debtor and creditor, then in theory the formula [base rate plus a credit risk premium] and the presumptive contract [market] rate approaches would yield the same final result.[10]

Volatility of Spread

The above discussion suggests that the spread is fairly stable. The r-squared between the prime and seven-year treasury rate is fairly high (0.8%) and the average premium over several time periods is fairly tight (ranged from 120 to 180 basis points as shown in Figure 4).

However, those observations, which are across long time periods, do not identify the volatility within the long time period. As shown in Figure 5, the spread sometimes dips below zero and at other times approaches 400 basis points. During one extreme period the spread exceeded 800 basis points. Any analysis of the spread should consider the spread that existed on the relevant date.

Roadmap to Reconcile the Cramdown and Market Interest Rate as of the Effective Date

It is much more difficult to reconcile the difference between the cramdown and market rates as of the Effective Date. We now need to increase the cramdown rate by 240 basis points, not 90 basis points. Because the bankruptcy judge already increased the seven-year treasury rate by 50 basis points, we need to see if there is a credible way to increase the seven-year treasury rate by 290 basis points.

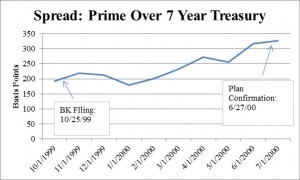

Spread as of the Relevant Date in Till

There is a surprisingly simple way to (superficially) accomplish this goal: use the spread that prevailed on the confirmation date in Till. As shown in Figure 6, the spread was over 300 basis points at that time. Thus, the credit risk premium discussed by the plurality in Till was applied to the prime rate at a time when the prime rate was abnormally high. Thus, there were effectively two credit risk premiums:

- the “official” version (in the case of Till, the 100 to 300 basis points range) and

- the “unofficial” version (in the case of Till, the difference between the prevailing and normal spread between the prime and seven-year treasury rate).

Any analysis of Till that ignores the “unofficial” credit risk premium may understate the appropriate adjustment to the seven-year treasury rate.

Figure 6[11]

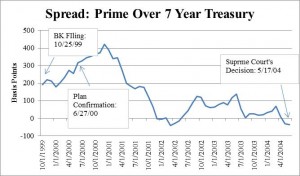

Spread During the Course of Till

However, anyone who goes down this path should be aware of the change in the spread during the course of Till. As shown in Figure 7, the spread peaked at over 400 basis points and then declined to less than zero by the time the Supreme Court issued its decision. Thus, the Supreme Court was addressing a time period with historically high spreads (because it was a retrospective analysis) at a point in time when the spread was historically low. This nuance was not addressed by the Supreme Court in Till.

Figure 7[12]

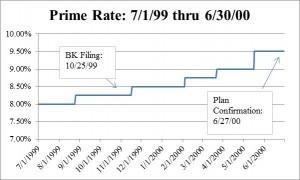

Was the Wrong Prime Rate Used in Till?

Another approach is to establish that the prime rate used in Till was too low. In Till, the 9.5% cramdown rate was determined as follows: 8.0% (prime rate) [13] plus 1.5% (credit risk premium). However, as shown in Figure 8, the prime rate was 9.5%, not 8.0% on the plan confirmation date. Notably, the prime rate was never 8.0% (or for that matter below 8.25%) at any point in time between the debtor’s bankruptcy filing and the confirmation of its reorganization plan.

Figure 8[14]

It is not clear why an 8.0%, and not a 9.5% prime rate was used in Till. However, the secured creditor’s testimony on the appropriate interest rate was proffered by fact witnesses who made subprime loans.[15] Thus, it is possible that the wrong prime rate was used in Till and the secured creditor (who was arguing for a much higher interest rate based on the subprime debtor’s lack of creditworthiness) did not identify this mistake.

As a practical matter, it could be said that the Supreme Court’s analysis in Till is implicitly comprised of “two wrongs that make a right”. The first wrong was using the prime rate when it was abnormally high (recall that the spread was over 300 basis points when the average spread is closer to 150 basis points). The second wrong was using an 8.0% prime rate when the prevailing prime rate was 9.5% (a 150 basis points mistake in the opposite direction). The net result of these two mistakes is effectively a wash.

Credit Risk Premium

A more reasonable way to reconcile the cramdown and market rates as of the Effective Date is to: (a) use the 140 basis point adjustment to the seven-year treasury rate that we made as of August 26, and (b) increase the credit risk premium from 150 basis points to 300 basis points, which is still within the 100 to 300 basis points range referenced in Till.

It may not be internally inconsistent to say we will not second-guess the 150 basis point credit risk premium as of August 26 yet use a higher credit risk premium as of the Effective Date. As discussed in the first part of this article, the market yield for approximately one month after the bench ruling was generally consistent with the market interest rate referenced in the bankruptcy judge’s opinion as of August 26. The market yield then increased from approximately 5.0% to approximately 6.3%. Something clearly changed during the intervening period. It appears reasonable to infer that perceptions of the debtor’s creditworthiness decreased (and the required credit risk premium increased) between late September and late October.

Conclusion

There has been a longstanding debate over the appropriate method to determine cramdown interest rates. The approach used in Momentive and Till (base rate plus a credit risk premium) is appealing to some in part because it is easy to understand. However, nuances over how to convert the prime rate to the treasury rate make this approach more complicated than it appears on the surface. Addressing these nuances suggests it is possible to arrive at the market interest rate while employing the approach used in Till and Momentive.

[1] The bankruptcy court’s bench ruling was in August 2014 and the opinion was finalized (after the debtor’s reorganization plan was altered to reflect changes prescribed in the bench ruling) in September 2014. The district court’s opinion was in May 2015.

[2] A similar process (with somewhat different assumptions) was used for the 1.5 lien debt. This article focuses on the larger first lien debt due to space limitations.

[3] The bankruptcy judge characterized this as an adjustment to the credit risk premium. However, because the intent of the adjustment is to put the treasury rate and prime rate on a similar basis, we will characterize it as an adjustment to the base rate.

[4] I have not seen the pricing formula used to arrive at 3.88%. However, the prescribed formula is contained in the judge’s opinion and the seven-year treasury rate declined by approximately 20 basis points during the relevant period.

[5] The data discussed in this article is monthly averages for the period July 1, 1969 (the beginning of the data series) through August 1, 2014 (the end of the data series that was available as of August 26, 2014).

[6] A r-squared (coefficient of determination) of 0.80 means 80% of the change in the dependent variable (in this case the prime rate) is predicted by the change in the independent variable (in this case the seven-year treasury rate).

[7] The predicted prime rate is (1.021 * .021) + .0114 = .0328, or 3.28%. 3.28% (predicted prime rate) less 2.10% (seven-year treasury rate) = 1.18%, or 118 basis points.

[8] Data obtained from https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/.

[9] Ibid

[10] Till at 484.

[11] Calculation based on monthly data obtained from https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/.

[12] Ibid

[13] Till at 465.

[14] Data from http://www.fedprimerate.com/wall_street_journal_prime_rate_history.htm.

[15] In re Till, 301 F.3d 583, 585 (7th. Cir. 2002).

Michael Vitti, CFA, joined Duff & Phelps in 2005. Mr. Vitti is a Managing Director in the Morristown office and is part of the Disputes and Investigations practice. He is also a member of the firm’s Complex Valuation and Bankruptcy Litigation group, focusing on issues related to valuation and solvency. Mr. Vitti has more than 19 years of valuation experience.

Mr. Vitti can be reached at: (973) 775-8250 or by e-mail to: Michael.Vitti@duffandphelps.com.

The author is not an attorney and is not offering legal advice. This article is written from a business valuation practitioner’s perspective who works on, among other things, bankruptcy-related matters.