The Cost to Obtain Liquidity

Studies in the Closely Held Company Valuation (Part II of II)

In the first part of this two-part discussion, the author identified six transaction risk factors attempting to sell a controlling (including 100 percent) interest in a closely held company. Those included: 1) an uncertain time horizon to complete the offering or sale; 2) “Make ready” accounting, legal, and other costs to prepare for and execute the offering or sale; 3) risk as to the eventual sale price; 4) uncertainty as to the form (e.g., stock or cash) of transaction sale proceeds; 5) inability to hypothecate the subject equity interest; and 6) investment banker or other brokerage fees. Risk factors one through five were summarized in the article “Measuring the DLOM for a Closely Held Company Controlling Interest” in the May 26, 2016 issue of QuickRead. A summary of risk factor six—investment banker or other brokerage fees—is presented here.

Valuation analysts (analysts) often value a controlling interest in a closely held company for various taxation, transaction, financing, accounting, and litigation reasons. Depending on the business valuation methods applied and the valuation variables selected, the analyst may initially conclude the value of the subject close company on a marketable (as if traded on a stock exchange) basis. If this is the case, the analyst may consider a valuation adjustment to this initial value indication in order to conclude the value of the illiquid close company. This discussion considers one of the factors analysts typically consider to measure the discount for lack of marketability (DLOM) related to the valuation of a controlling (including 100 percent) interest in the close company.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]Resources:

Business Valuation Certification and Training Center

Advanced Valuation: Applications and Models Workshop

On-Demand Webinar: Liquidity Discounts: Option Based Methods

[/su_pullquote]

This factor relates to the investment banker or other brokerage fees associated with the sale of the closely held company. This factor is often measured by empirical data, often called “cost to obtain liquidity studies.”

Part one of this two-part discussion presented in the May 26, 2016 issue of QuickRead, summarized the following topics:

- Various empirical and theoretical models analysts use to estimate the DLOM;

- Application of the DLOM to the closely held company valuation; and

- Factors analysts consider in the DLOM selection.

The appropriate DLOM valuation adjustment is a function of both:

- The business valuation methods applied and the valuation variables selected; and

- The level of value that is the objective of the subject business valuation.

The DLOM value decrement related to the closely held company is due to the following two factors:

- The absence of a ready private placement market; and

- Flotation costs (which would be incurred in achieving liquidity through a public offering).

As mentioned in the first part of this two-part discussion, the business owner faces the following transaction risk factors when attempting to sell a controlling (including 100 percent) interest in a closely held company:

- An uncertain time horizon to complete the offering or sale;

- “Make ready” accounting, legal, and other costs to prepare for and execute the offering or sale;

- Risk as to the eventual sale price;

- Uncertainty as to the form (e.g., stock or cash) of transaction sale proceeds;

- Inability to hypothecate the subject equity interest; and

- Investment banker or other brokerage fees.

Risk factors one through five were summarized in the article “Measuring the DLOM for a Closely Held Company Controlling Interest” in the May 26, 2016 issue of QuickRead. A summary of risk factor six—investment banker or other brokerage fees—is presented below.

One analyst consideration in the DLOM estimation for a closely held company valuation is the cost to obtain liquidity studies. These DLOM measurement studies only apply to the analysis of controlling ownership interests. This is because the cost to obtain liquidity studies are based on transactions of closely held company controlling interests.

The Cost to Obtain Liquidity Studies

The data that analysts often consider to estimate a controlling interest DLOM are summarized below.

Transaction Costs

The various transaction costs related to the closely held company sale include the following:

- Auditing and accounting fees. These fees are incurred in preparing financial statements and related information for potential buyers and/or underwriters.

- Legal costs. These costs are incurred in preparing documents, investigating contingent liabilities, and negotiating warranties.

- Administrative costs (i.e., opportunity costs). These costs are related to the time committed by company owners and managers to deal with accountants, lawyers, potential buyers, and/or their representatives.

- Transaction and brokerage costs. These business broker, investment banker, or other transaction intermediary costs are sometimes referred to as “flotation costs.” When these transaction costs are expressed as a percentage of the sale price, the percentage cost is referred to as the “gross spread.”

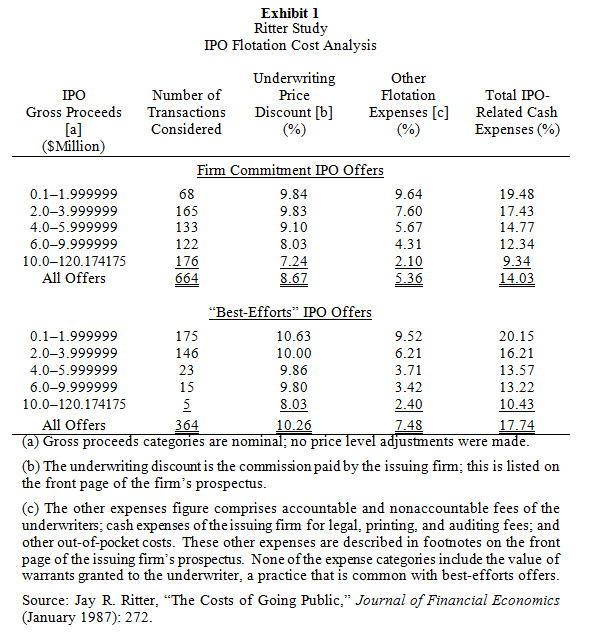

In a study published in 1987, Jay Ritter analyzed the flotation costs typically incurred by the security issuer in an IPO.[1] These flotation cost data are summarized in Exhibit 1.

The Ritter study indicates that larger companies generally negotiate lower underwriting fees as a percent of the IPO gross proceeds. More current flotation cost information is presented in a study conducted by Jay Ritter and Hsuan-Chi Chen published in 2000.[2]

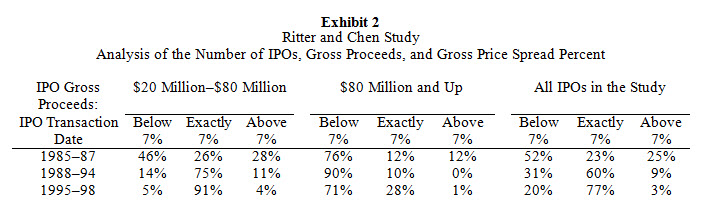

In the “Seven Percent Solution,” the authors examined the price spread (i.e., the underwriter price discount) from 3,203 firm commitment IPOs from January 1985 to December 1998. The selected IPO transactions all had domestic gross proceeds of at least $20 million before the exercise of the over-allotment option. Exhibit 2 summarizes the results from this Ritter and Chen study.

Ritter and Chen concluded that a significant number of IPOs were completed with a gross price spread of exactly seven percent. In the 1985 to 1987 period, 23 percent of all IPOs had a seven percent gross price spread. Of the IPOs analyzed in the 1998 to 1994 period, the amount of transactions with a seven percent price spread increased to 60 percent.

For 1995 to 1998, 77 percent of all IPOs had a gross price spread of exactly seven percent. Ritter and Chen observed that the price spread is larger for smaller companies. This evidence indicates that a reasonable underwriter price discount for an IPO is seven percent for companies with IPO gross proceeds exceeding $20 million.

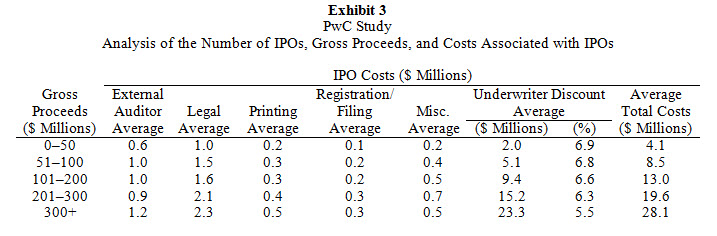

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (PwC) published a study on IPO costs in September 2012.[3] PwC authors Martyn Curragh, Henri Leveque, and Neil Dahr examined both the costs a company incurs to make an IPO and the ongoing costs a company incurs to remain a publicly traded entity. The PwC study analyzed over 380 IPO transactions between January 1, 2009, and June 30, 2012. The PwC study examined the following costs associated with the IPO transactions:

- Underwriter fees; and

- Legal, accounting, and other fees directly attributable to the IPO.

Exhibit 3 summarizes the PwC IPO cost study.

The PwC study concluded that the average cost paid to the IPO underwriter ranged from 5.5 percent of gross proceeds to 6.9 percent of gross proceeds. The PwC study suggests a trend of decreasing costs as a percentage of gross IPO proceeds as the size of the IPO increases. The PwC study quantified additional costs related to an IPO. It suggests that the total costs associated with an IPO, on a percentage of gross proceeds, is actually greater than the 5.5 percent to 6.9 percent demanded by the underwriter.

Each of the above-described cost to obtain liquidity studies concluded that larger companies can negotiate lower underwriter fees, as a percent of the IPO gross proceeds. The PwC study presented evidence that reasonable underwriter fees range from approximately five percent to seven percent, depending on the size of the IPO. The study also concluded that the additional costs associated with an IPO make the total costs, as a percentage of gross proceeds, greater than five percent to seven percent.

The Ritter and Chen study presented evidence that typical underwriter fees are approximately seven percent of the IPO gross proceeds. That study did not analyze companies with IPO gross proceeds of less than $20 million. The Ritter study did analyze companies with IPO gross proceeds under $20 million, indicating costs of over ten percent of the IPO proceeds for smaller transactions.

The seller of a closely held company may also incur other costs in addition to:

- The underwriter fees; and

- The “other costs” described above.

In order to measure the appropriate DLOM, the analyst should consider all costs to sell a controlling interest in the closely held company.

Summary and Conclusion

Analysts often value closely held companies for various taxation, transaction, financing, accounting, and litigation reasons. Depending on: 1) the valuation approach and valuation method applied; and 2) the benchmark valuation variable data used, the analyst may conclude the value of the close company on a marketable basis. That is, the use of capital market data to derive pricing multiplies, discount rates, and capitalization rates concludes the value of the subject company as if it was freely traded on a stock exchange. Since the closely held company is not freely traded, the analyst may need to consider a DLOM valuation adjustment to conclude the value of the subject company.

This discussion summarized the factors analysts typically consider in order to measure the DLOM for a controlling (including 100 percent) interest in a closely held company.

[1] Ibid.: 272.

[2] Chen and Ritter, “The Seven Percent Solution.”

[3] Martyn Curragh, Henri Leveque, and Neil Dhar, et al., “Considering an IPO? The Costs of Going and Being Public May Surprise You,” PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (September 2012), http://www.pwc.com/us/en/transaction-services/publications/cost-of-ipo-september-2012.jhtml (accessed December 4, 2014).

Robert Reilly, CPA, ASA, ABV, CVA, CFF, CMA, CBA, is a managing director of Willamette Management Associates based in Chicago. His practice includes business valuation, forensic analysis, and financial opinion services. Throughout his notable career, Mr. Reilly has performed a diverse assortment of valuation and economic analyses for an array of varying purposes.

Mr. Reilly is a prolific writer and thought leader who can be reached at (773) 399-4318, or by e-mail to rfreilly@willamette.com.