Analyzing Lost Earning Capacity for the Self-Employed

Income of Partners and Owners of Pass-through Entities (Part I of II)

This is a two-part article where the author discusses the methodology for assessing the lost earning capacity of a self-employed person. This, basically, is the same as that for a traditional wage and salary worker. Even though the methodology is the same, assessing the data for the self-employed is different. The loss calculations are not just based on W-2’s or payroll stubs as may be used for traditional wage and salary employees. Data from differing Internal Revenue Service forms used for reporting business income must be reviewed. In addition, there are nuances when assessing a person who is self-employed that must be considered. This article provides an overview for analyzing the lost earning capacity of the self-employed and discusses why this category of work provides unique assessment situations.

The methodology for assessing the lost earning capacity of a self-employed person is, basically, the same as that for a traditional wage and salary worker. In an injury case, the expert examines data to determine lost past and future annual earnings through the injured person’s projected worklife, assumes a growth factor, considers fringe benefits, and if required, adjusts for income taxes. Any projected earnings loss is then offset by the mitigating income the injured person is assumed to be able to achieve and the remaining future losses are discounted to present value.1

The methodology for assessing the lost earning capacity of a self-employed person is, basically, the same as that for a traditional wage and salary worker. In an injury case, the expert examines data to determine lost past and future annual earnings through the injured person’s projected worklife, assumes a growth factor, considers fringe benefits, and if required, adjusts for income taxes. Any projected earnings loss is then offset by the mitigating income the injured person is assumed to be able to achieve and the remaining future losses are discounted to present value.1

[su_pullquote align=”right”]Resources:

Elements of Lost Profits and Introduction to Lost Profits

Special Considerations for Lost Profits Calculations

The Ins and Outs of Present Value Calculations Review of the Three Commonly Accepted Methods

Foundations of Financial Forensics Workshop

[/su_pullquote]

Even though the methodology is the same, assessing the data for the self-employed is different. The loss calculations are not just based on W-2’s or payroll stubs as may be used for traditional wage and salary employees. Data from differing Internal Revenue Service forms used for reporting business income must be reviewed. This data provides a basis for proving the self-employed’s earning capacity.

In addition, there are nuances when assessing a person who is self-employed that must be considered. This article provides an overview for analyzing the lost earning capacity of the self-employed and discusses why this category of work provides unique assessment situations.

Self-Employed

The Internal Revenue Service says to be considered self-employed:

- You carry on a trade or business as a sole proprietor or an independent contractor,

- You are a member of a partnership that carries on a trade or business, and

- You are otherwise in business for yourself including a part-time business.2

A more general definition for self-employed is:

“Self-employed is a situation in which an individual works for himself or herself instead of working for an employer that pays a salary or wage. A self-employed individual earns their income through conducting profitable operations from a trade or business that they operate directly.”3

Assessing the lost earning capacity of an injured self-employed person brings an expert to the point where personal damages and commercial damages touch. For most self-employed individuals, the profits of their business are their earnings. When the self-employed is injured, often the revenue and profits of the business decrease. In turn, this means the reported earnings of the self-employed decrease.

The decline in profits may be for only a short period of time or permanent. This is because the injury to the owner may cause the business to be damaged for a short (or long) period of time, or destroyed. Because the source of earnings is from the business, it is important for any expert calculating the lost earning capacity of a self-employed person to keep in mind the claim is for personal damages. The claim is not for lost profits due to an injury to the business. Although, in reality, both a lost earning capacity and lost profits claim would use much of the same data, the emphasis and wording must remain on lost earning capacity.

Income/Expenses

Self-employed individuals range from those who “own their job” to those who own and operate businesses with numerous employees. They range in professions from painters and electricians to attorneys and physicians. Depending on the type of work and size of business, the self-employed may report income on a variety of IRS forms.

Perhaps the most commonly used form for reporting self-employed income is Schedule C (Profit and Loss from Business). This form is attached to the form 1040 income tax return filed by the taxpayer. Schedule C shows the revenue generated by the business expenses deducted and the net income for the business. The self-employed worker pays personal income taxes on any profits generated.

In addition, the self-employed also files a Schedule SE that calculates the self-employment tax due on this income. The self-employment tax is paid to Social Security and Medicare. Because the self-employed person is not only employee but also employer, the self-employment tax calculates the payment of both the employee and employer portions of FICA.4

The IRS definition of self-employed includes participation in a partnership. If the self-employed person participates in a partnership, he or she will receive a K-1 that is tied to the revenue, expenses, and profits (losses) reported on a form 1065, partnership income return. This partnership may be for a limited partnership, limited liability company, or limited liability partnership. A K-1 will provide the amount of non-passive income earned by the self-employed along with the level of ownership he or she has in the partnership. The non-passive income will be reported on the Schedule E attached to the self-employed person’s form 1040. In addition, a Schedule SE should also have been filed with the form 1040 showing the self-employment taxes paid on this K-1 income.

The self-employed may have created an S corporation which files a form 1120S or, if the business is large enough, a corporation which files a form 1120. If the self-employed works for a corporation he or she owns, they will receive a W-2 to report annual earnings. Any profits generated by the corporation is taxed and paid by the corporation through its form 1120 filing. However, if the self-employed owns or is part owner in an S corporation, more than likely he or she will receive a W-2 reflecting wages and salary and a K-1 showing non-passive income from the corporation.

Therefore, it is important for an expert to understand the structure of the self-employed person’s business. The structure of the business will direct that expert to the forms needed for assessing the self-employed’s earnings. For a sole proprietorship, a series of Schedule C’s will provide the trend in annual revenue, expenses, and income generated by the injured person. A Schedule SE will also provide information as to the self-employment tax paid by the self-employed. At least a portion of the self-employment tax (the portion normally paid by the employer) may be included by some experts as an additional work related expense.5

For a self-employed in a partnership (e.g., an accounting or law firm), the self-employed person’s K-1 will show his or her income stream. This non-passive income will also be reflected on the Schedule E. This provides for a good crosscheck on information. In addition, the Schedule E may also show if the self-employed person’s spouse is a partner. If so, this may require additional research to determine the level of work performed by the spouse to generate the income reported on the K-1’s. Again, the Schedule SE should be reviewed to determine the self-employment taxes paid on this income.

If the self-employed business is structured as an S corporation, both W-2’s and K-1’s should be sought. The W-2 will show the portion of earnings that are wages and salary. The other income will be reflected in the K-1. If the person was truly self-employed in this S corporation business, then his or her time and effort went to generating the income reported on the K-1. And, it is the combined total (W-2 and K-1) which properly reflects the earning capacity of the self-employed person.

Many S corporations are no larger than businesses shown on Schedule C’s or small partnerships. Although there is more recordkeeping involved with an S corporation, there is a good reason for a self-employed person to create one. That reason involves self-employment taxes. For standard wage and salary employees, FICA (Social Security and Medicare) taxes are paid by the employee and the employer on the employee’s W-2 income.6 For the self-employed, they are the employee and employer; therefore, they pay both portions of the tax, hence the term self-employment tax. No FICA taxes are paid on the K-1 non-passive income from an S corporation.

As an example, for a self-employed person earning $200,000 and reporting income on a Schedule C, his or her total self-employment (FICA) tax would be $20,050.30.7 If the same person created an S corporation, paying himself or herself $50,000 in W-2 wages and $150,000 in K-1 non-passive income, the total self-employment tax would be $7,064.78. This is a savings to the self-employed of nearly $13,000 in FICA taxes.8

The participation of a spouse may or may not be reflected in the tax information forwarded to an expert. In a Schedule C filing only one self-employed person is listed. The spouse’s contribution is usually not reflected. Under most circumstances, the income reported by the self-employed includes the earnings generated by both.

As an example, an electrician may work out of his truck and provide the source of revenue for his sole proprietorship. His wife operates the office from their home; answering the phone, mailing invoices, collecting payments, paying bills, and keeping the business’ books. Her work contribution is not reported in the Schedule C. Therefore, it is important for an expert to understand the contribution, if any, made by the self-employed person’s spouse.

The facts and circumstances of each case may determine if the self-employed person’s earnings should be reduced by the spouse’s work contribution. The number of hours worked, the cost to hire an employee to perform the same work, and if the self-employed could have performed the same work but allocated that work to the spouse are only a few of the factors to be considered. It is possible the self-employed’s income could be reduced by the amount of wages that would have been paid to an employee to perform the spouse’s work. And, the spouse then claim lost earnings in the amount deducted because the spouse lost income when the self-employed was injured and the business closed. This means both spouses have lost income due to the injury.9

Spouses may also work and contribute to the success and income generation of a partnership and/or S corporation. However, a spouse may be a part owner (especially in an S corporation) and not perform any work. In reviewing K-1’s, an expert should determine if the self-employed person’s spouse has any ownership and if so, the amount of time spent working at the business. If there is little or no participation, it could be argued the spouse’s K-1 income is part of the self-employed person’s earning capacity because the self-employed person generated that income. This is an issue best addressed with the hiring attorney prior to including in any analysis.

The review of Schedule C’s, K-1’s, and/or W-2’s should provide a clear picture of the earning capacity of the injured self-employed. But sometimes the results show a level of income below what could be earned working as a wage and salary employee. As an example, an independent long-haul truck driver may show an annual average income of only $20,000 on his Schedule C’s. While at the same time, the average for the employees working in the same position as traditional employees are earning $41,000.10

In this situation, an expert could provide a range of lost earning capacity with one based on remaining an independent long haul truck driver earning $20,000 per year and the other based on becoming a long haul trucker for a trucking company earning $41,000 per year. The assumption of becoming an employee of a trucking company is based on the reasonable (economic) man theory. Wanting to maximize his earning capacity, the self-employed will make the economic decision to give up being self-employed to make more money as an employee.

One reason a self-employed person’s income may be less than the standard wage and salary workers’ income could be depreciation. Should the self-employed choose to apply accelerated depreciation, his or her annual income will be lesser or greater than if straight-line depreciation had been used. The impact of the depreciation on the self-employed’s income will depend on if it applies to the early years or toward the end of an asset’s work life.

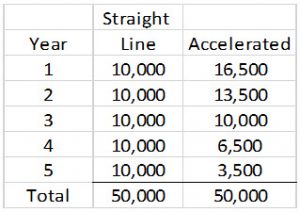

Straight-line depreciation is the method for computing depreciation based on the working life of the asset. The asset’s cost, less expected salvage value, is divided by the number of years the asset is expected to work. Then each year’s value is subtracted from the self-employed business’ revenue. This is the simplest depreciation method.

Accelerated depreciation is any method of depreciation that allows greater deduction in earlier years of life of an asset. “While the straight line depreciation method spreads the cost evenly over the life of an asset, an accelerated depreciation method allows the deduction of higher expenses at first after the purchase, and lower expenses as the depreciated item ages.”11

If the self-employed has applied an accelerated depreciation method on its Schedule C, an adjustment of the deprecation schedule to straight line may provide a more accurate reflection of the ongoing earning capacity of the injured self-employed. Smoothing the depreciation increases the income for the early years of the asset’s life and decreases the income for its later years. Using a straight-line method removes the artificial increases or decreases in annual expenses brought about by applying different deprecation amounts over each year of the asset’s life.

The following table shows the annual difference in depreciation expense for an asset whose purchase cost is $50,000 and has a useful life of five years. This example has assumed no salvage value. It shows both the straight-line depreciation expense and the accelerated depreciation expense based on the sum of the years’ digits method.12

The example shows how the self-employed person’s income would be affected if the expert received a Schedule C for only the first three years of the assets life or the last three years.

A similar adjustment may be made for self-employed persons getting income from partnerships or S corporations. However, this type of adjustment requires a review of the form 1065 or 1120S filed by the business. Any change in the depreciation amount would be reflected as a change in the business income. In addition, a change in the deprecation method would not only impact the business filing (form 1065 or 1120S) but the resulting K-1’s as well. This is a more complicated process than adjusting a Schedule C. Many experts choose not to make adjustments for depreciation on partnership or S corporation returns.

In Part II of this article, the author addresses issues involving fringe benefits, worklife, mitigation, and value of the business.

[1] This article discusses the lost earning capacity of a self-employed person in a personal injury case. Â In most wrongful death matters, the overall assessment would be the same without the consideration of mitigation, but with the inclusion of personal consumption. Â Additional adjustments would have to be made in a death case, those have not been discussed.

[2] Internal Revenue Service, www.irs.gov

[3] Investopedia, www.investopedia.com

[4] The Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA). Â This act provides for the employee and employer contributions to Social Security and Medicare.

[5] This is especially true in jurisdictions where state and federal income taxes must be considered in lost earning capacity calculations.

[6] Generally, each pays 7.65% on the employee’s income with 6.20% going to Social Security and 1.45% going to Medicare.  There is a cap on the Social Security tax, but none on the Medicare tax, www.ssa.gov

[7] Schedule SE, Self-Employment Tax, 2015, www.irs.gov

[8] Although the W-2 would report only a 7.65% payment of FICA taxes by the self-employed, the remaining 7.65% paid by the self-employed would show up as a corporate expense.  This reduces the business’ overall income and ultimately, the self-employed’s earnings.  Therefore, this calculation has included the entire 15.30% FICA tax to reflect the amount being paid by the self-employed person.

[9] In this situation, the spouse should seek re-employment to offset the earnings loss. Â The spouse may not be able to start a new job due to caring for the injured self-employed or because of not being qualified for the prior work performed. Â This requires a more detailed vocational analysis that is not discussed in this article.

[10] Texas Workforce Commission, Labor Market Information, Wages by Profession, www.tracer2.com

[11] Investopedia, www.investodpedia.com

[12] Sum of the years’ digits takes the asset’s expected life and adds together the digits for each year.  If the asset has a five-year useful life, the sum of the years’ digits is 15 (1+2+3+4+5=15).  Each digit is divided by the sum to determine the percentage by which the asset should be depreciated, starting with the highest number (5/15=.33, the first year’s depreciation expense would be 33% of the cost of the asset less salvage value, if any).

Allyn Needham, PhD, CEA, is a partner at Shipp, Needham & Durham, LLC, a Fort Worth-based litigation support consulting expert services and economic research firm. Prior to joining Shipp, Needham & Durham, he was in the banking, finance, and insurance industries for over twenty years. As an expert, he has testified on various matters relating to commercial damages, personal damages, business bankruptcy, and business valuation. Dr. Needham has published articles in the area of financial economics and forensic economics and provided continuing education presentations at professional economic, vocational rehabilitation and bar association meetings.

Dr. Needham can be reached at (817) 348-0213, or by e-mail to aneedham@shippneedham.com.