Proponents of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Always Want More Cowbell

The More Cowbell skit can be repurposed to explain debates over the efficient market hypothesis. Many proponents of the efficient market hypothesis may initially find it annoying that nonbelievers do not share their view. However, believersâ faith in the efficient market hypothesis is dependent on nonbelievers continuing to try, but inevitably failing, to âbeat the market.â The efficient market hypothesis only works when investors can be âfree ridersâ that enjoy the fruits of nonbelieversâ labor, which make the market efficient. Thus, believers in the efficient market hypothesis should always want âmore cowbell,â which in this context is nonbelievers who try to âbeat the market.â This is the first of a two-part article. This article addresses the efficient market hypothesis. The second article is titled: The Debate Over the Efficient Market Hypothesisâ Effect on Contested Valuations.

Summary/Introduction

Many fans of pop culture are familiar with Saturday Night Liveâs âMore Cowbellâ skit. Will Ferrellâs character (a member of the Blue Oyster Cult) annoyingly plays a cowbell during the bandâs recording of âDonât Fear the Reaper.â After the other band members complain, Christopher Walkenâs character (a successful music producer) counterintuitively proclaims: âI got a fever! And the only prescriptionâŚis more cowbell!â The previously annoyed band members, after hearing the music producerâs counterintuitive yet presumably informed and expert view, decide they want more cowbell too.

The More Cowbell skit can be repurposed to explain debates over the efficient market hypothesis. Many proponents of the efficient market hypothesis may initially find it annoying that nonbelievers do not share their view. However, believersâ faith in the efficient market hypothesis is dependent on nonbelievers continuing to try, but inevitably failing, to âbeat the market.â  The efficient market hypothesis only works when investors can be âfree ridersâ that enjoy the fruits of nonbelieversâ labor, which make the market efficient. Thus, believers in the efficient market hypothesis should always want âmore cowbell,â which in this context is nonbelievers who try to âbeat the market.â

This is the first of a two-part article. This article addresses the efficient market hypothesis. The second article is titled: The Debate Over the Efficient Market Hypothesisâ Effect on Contested Valuations.

Overview of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

The efficient market hypothesis (setting aside issues related to inside information)[1] posits that attempts to âbeat the marketâ are destined to fail. Failure is inevitable because there are potential market participants trying to profit on both sides of a transaction and their efforts cancel each other out.  This results in a net loss for active investors as the costs they incur while trying to âbeat the marketâ exceed the excess returns generated from this endeavor.

Burton Malkiel provided one of the most colorful and famous descriptions of the efficient market hypothesis. He stated, in his book A Random Walk Down Wall Street: âA blindfolded monkey throwing darts at a newspaperâs financial pages could select a portfolio that would do just as well as one carefully selected by experts.â Perhaps nothing captures the essence of being unable to âbeat the marketâ better than the inability to beat a dart-throwing monkey in a security-picking contest.

Dependency on âInsaneâ Investors

A common clichĂŠ is the so-called definition of insanity: repeating the same mistakes yet expecting different results. The efficient market hypothesis is predicated on the assumption that there are many investors who continue to try, but consistently fail over the long-term, to âbeat the market.â It seems fair to say that proponents of the efficient market hypothesis have a symbiotic relationship with people they believe are âinsaneâ under this definition of âinsanity.â

âLow Costâ vs. âSearch for Alphaâ Investing Strategies

Perhaps the best way to classify someoneâs view on the efficient market hypothesis is to identify how they invest their money. Strong believers in the efficient market hypothesis are expected to invest in low cost index funds to obtain market-level returns at the lowest possible cost. Strong disbelievers in the efficient market hypothesis are expected to invest in higher cost (i.e., actively managed) strategies with the expectation that above market returns on a cost-adjusted basisâi.e., alphaâcan be achieved. Investors who are less dogmatic, hedge their bets and fall somewhere in between these two ends of the continuum.

Which View is Correct? The 2013 Nobel Prize Perspective

The 2013 Nobel Prize in Economics went to both the founder (Eugene Fama) and a leading critic (Robert Shiller) of the efficient market hypothesis.[2]Â Awarding the prize to both, at the same time, was contemporaneously characterized as âunlikely,â[3] âseemingly contradictory,â[4] âshows a certain flair for irony;â[5] and was âlike giving a prize to the Yankees and the Red Sox.â[6] Â It seems fair to say that the selection of these economists for the Nobel Prize suggests the debate over the efficient market hypothesis may be unsettled.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (the group that awards the Nobel Prize), in the press release announcing the recipients, stated:

There is no way to predict the price of stocks and bonds over the next few days or weeks. But it is quite possible to foresee the broad course of these prices over longer periods, such as the next three to five years. These findings, which might seem both surprising and contradictory, were made and analyzed by this yearâs Laureates, Eugene Fama, Lars Peter Hansen, and Robert Shiller.[7]

Warren Buffet: Do As I Say, Not As I Do

Many consider Warren Buffet to be the best example of someone who can consistently âbeat the market.â Mr. Buffet has famously made many more âwinningâ than âlosingâ investment-related decisions during his long tenure at the helm of Berkshire Hathaway. This track record may make him the patron saint for value investing.

Mr. Buffett also appears to encourage this characterization as evidenced by the structure of Berkshire Hathawayâs annual report. Immediately after the table of contents, without any introduction, is a table that compares the annual percentage change in (a) Berkshire Hathawayâs book value per share, (b) Berkshire Hathawayâs market value per share, and (c) the S&P 500 with dividends included for every year between 1965 and 2016. There is no need to âtellâ readers about Berkshire Hathawayâs strong performance when it is more compelling to âshowâ them.

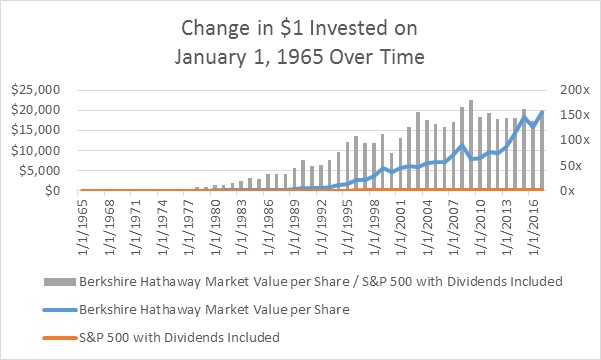

As shown in Figure 1, $1 invested in Berkshire Hathaway stock on January 1, 1965 bought approximately $20,000 worth of Berkshire Hathaway stock as of December 31, 2016 whereas $1 invested in the S&P 500 index returned less than $130 during the same period.[8] Â Thus, an investment in Berkshire Hathaway was worth greater than 150x more than an investment in the S&P 500 at the end of this 52-year period.

Figure 1[9]

This is a clear-cut case of a firm âclobbering the marketâ over a sustained period. This is not just a victory for active management. This outcome is like the Bears beating the Redskins 73 to nothing in the 1940 NFL Championship Game, or Secretariat winning the Belmont Stakes by 31 lengths, which espn.com ranked as the worst (or best, depending on perspective) two blowouts in sports history.[10]

Nevertheless, Mr. Buffet believes it is extremely difficult to identify someone who is expected to consistently âbeat the marketâ as he and his colleagues have done during his long and successful career. Mr. Buffet consistently advocates for investors to choose low cost index funds because they are expected to outperform actively managed funds on a cost-adjusted basis. He also âputs his money where his mouth isâ in at least two important ways.

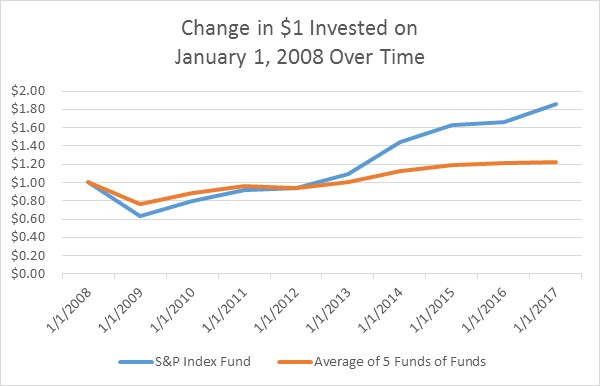

First, Mr. Buffet made a public bet, which put some money on the line but seems to be more about âbragging rights.â He wagered that no investment professional could identify at least five hedge funds that could outperform the low-cost Vanguard S&P 500 index fund over a 10-year period. Only one person took the other side of that wager: Ted Seides. Mr. Seides picked five funds-of-funds. It is now nine years into that bet with only one year to go. As shown in Figure 2, it seems extremely likely that Mr. Buffet will win this bet.

Figure 2[11]

Second, Mr. Buffet put âhis money where his mouth isâ in his personal will. Mr. Buffett explained in the 2013 Berkshire Hathaway annual report:

My money, I should add, is where my mouth is: What I advise here is essentially identical to certain instructions Iâve laid out in my will. One bequest provides that cash will be delivered to a trustee for my wifeâs benefitâŚMy advice to the trustee could not be more simple: Put 10% of the cash in short-term government bonds and 90% in a very low-cost S&P 500 index fund. (I suggest Vanguardâs). I believe the trustâs long-term results from this policy will be superior to those attained by most investorsâwhether pension funds, institutions, or individualsâwho employ high-fee managers.[12]

Mr. Buffetâs rationalization for the âdo as I say, not as I doâ advice appears to be that he believes he is one of the rarefied few who can repeatedly âbeat the market.â Mr. Buffet says he only identified early on (i.e., in time to substantially profit from the identification) âten or soâ professionals that were âhighly likely to out-perform the S&P over long stretches.â[13] He further states:

There are no doubt many hundreds of peopleâperhaps thousandsâwhom I have never met and whose abilities would equal those of the people Iâve identified. The job, after all, is not impossible. The problem simply is that the great majority of managers who attempt to over-perform will fail. The probability is also very high that the person soliciting your funds will not be the exception who does well.[14]

This is an important observation for proponents of the efficient market hypothesis. Mr. Buffet is perhaps the best person to lead the charge against the efficient market hypothesis. However, he has not assumed the mantle in that debate. To the contrary, he has effectively endorsed the efficient market hypothesis.

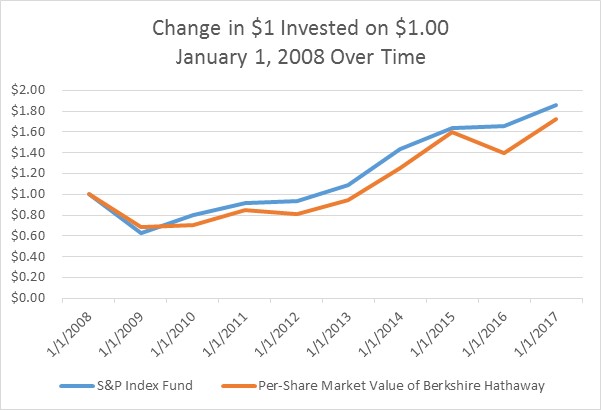

Notably, it is also not clear that Berkshire Hathaway has âbeat the marketâ for a while. More specifically, it is not clear if Berkshire Hathaway would have won the bet shown in Figure 2. As shown in Figure 3, Berkshire Hathaway appears, at least on the surface, to have underperformed relative to the S&P 500 during the nine-year term of the bet.

Figure 3

The discussion regarding Figure 3 is qualified because Berkshire Hathawayâs annual report may state that the change in the market value for its shares understates relative performance because it is on an after-tax basis whereas the change in the S&P 500 is on a pre-tax basis. (âThe S&P 500 numbers are pre-tax whereas the Berkshire numbers are after-tax [emphasis in original].â) However, it is not clear if, or why, that logic applies to Berkshire Hathawayâs market value per share and not just its book value per share. Also, if that logic does apply to Berkshire Hathawayâs market value per share, it is not clear why a similar disclaimer was not made to the data in Figure 2 within Berkshire Hathawayâs annual report.

Rise of the Machines

An increase in automation across many industries and disciplines seems inevitable. This includes the security-picking profession.

BlackRock recently made an announcement that generated several âRise of the Machineâ references. Titles of podcasts or articles include âBlackRock: Rise of the Machines on Wall Street?â in the Wall Street Journal[15] and âAt BlackRock, Machines are Rising Over Managers to Pick Stocksâ[16] in the New York Times.

The New York Times article said:

The initiative is the most explicit action by a major fund management firm in reaction to the exodus of investors from actively managed stock funds to cheaper funds that track every variety of index and investment theme.

The Pendulum

It seems fair to say that the efficient market hypothesisâ efficacy will always be on a pendulum. Active investors will seek to take advantage of perceived market inefficiencies, which subsequently results in fewer market inefficiencies. Active investors will reduce their efforts as the market becomes more efficient, which in turn plants the seeds for more market inefficiencies down the road.

From a practitionerâs perspective, a key issue is the relevant range of the pendulum. It may be fair to determine that a securityâs price is âwrongâ because it is under- or overvalued on an intrinsic value basis. But it is much harder to compellingly argue a securityâs price is âwrongâ by (an) order(s) of magnitude.

The second part of this article will address this topic.

Conclusion

Debates over the efficient market hypothesis can be quite interesting. Normally, a vigorous and well-prepared rebuttal by highly qualified and motivated people will cast doubt on the validity of the other sideâs argument. But this is no ordinary debate. The debate is akin to fighting the monster in a science fiction movie that feeds off the energy used by the heroes in their attempt to defeat the monster.

The unusual nature of the debate results in a paradox: the more one fights it, the stronger the monster (or efficient market hypothesis) becomes. It is for this reason that believers in the efficient market hypothesis should encourage dissent. Simply put, proponents of the efficient market hypothesis can never have enough cowbell (aka dissent) as their demand for it is insatiable.

[1] Inside information is incorporated in the strong form, but not semi-strong or weak forms, of the efficient market hypothesis.

[2] Lars Hansen also was a recipient of the 2013 Nobel Prize in economics. Dr. Hansenâs selection has been characterized as a âperfect balanceâ between the two extremes represented by Dr. Fama and Dr. Shiller. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-10-14/fama-hansen-shiller-share-nobel-economics-prize-academy-says

[3] https://mobile.nytimes.com/2013/10/15/business/3-american-professors-awarded-nobel-in-economic-sciences.html: âThe two men, leading proponents of opposing views about the rationality of financial marketsâa dispute with important implications for investment strategy, financial regulation, and economic policyâwere joined in unlikely union Monday as winners of the Nobel Memorialize Prize in Economic Science (emphasis added).â

[4] http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2013/10/economics-nobel-prize: âTogether, Meers, Fama, Hansen, and Shiller make a seemingly contradictory group of people to win the prize together. While Mr. Fama has been hailed as the father of the âefficient marketâ hypothesis, Mr. Shiller is famous for knocking holes in the exact same theory. Yet viewed in terms of their contributions, they are a more cohesive group (emphasis added).â

[5] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-10-14/fama-hansen-shiller-share-nobel-economics-prize-academy-says: Andrew Lo, a finance professor at MITâs Sloan School of Management said, âthe Nobel committeeâs decision in giving the award to Fama and Shiller âdefinitely shows a certain flair for irony.â The message, he added is that âfinancial markets can be efficient most of the time, but every once in a while they break down and then we need to develop better analytics to be able to understand them (emphasis added).ââ

[6] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-10-14/fama-hansen-shiller-share-nobel-economics-prize-academy-says: ââItâs like giving a prize to the Yankees and the Red Sox,â [Robert Snow, winner of the Nobel economics prize in 1987] said, comparing the competing theories to the rivalry between the New York and Boston baseball teams. âWhat it suggests is there really isnât a settled doctrineâ in finance (emphasis added).â

[7] http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/2013/press.html

[8] Berkshire Hathawayâs annual report explains that the data understates Berkshire Hathawayâs relative performance. The most recent annual report states: âThe S&P 500 numbers are pre-tax whereas the Berkshire numbers are after-tax. If a corporation such as Berkshire were simply to have owned the S&P 500 and accrued the appropriate taxes, its results would have lagged the S&P 500 in years when that index showed a positive return, but would have exceeded the S&P 500 in years when the index showed a negative return. Over the years, the tax costs would have caused the aggregate lag to be substantial (emphasis in original).â This characterization makes sense for Berkshire Hathwayâs book value per share. It is not clear if, or why, that characterization is meant to apply to Berkshire Hathawayâs market value per share too.

[9] Data from p. 2 of Berkshire Hathawayâs 2016 Annual Report.

[10] http://www.espn.com/moresports/story/_/id/13670468/worst-blowouts-sports-history-ranks-100-most-stunning-routs-nos-25-1

[11] Data from p. 22 of Berkshire Hathawayâs 2016 Annual Report.

[12] Berkshire Hathawayâs 2013 Annual Report at p. 20.

[13] Berkshire Hathawayâs 2016 Annual Report at p. 24.

[14] Ibid.

[15] http://www.wsj.com/podcasts/blackrock-rise-of-the-machines-on-wall-street/0E12B88C-5996-4795-921D-D8EA87192A20.html

[16] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/28/business/dealbook/blackrock-actively-managed-funds-computer-models.html

Michael Vitti, CFA, joined Duff & Phelps in 2005. Mr. Vitti is a managing director in the Morristown office and is part of the Disputes and Investigations practice. He is also a member of the firmâs Complex Valuation and Bankruptcy Litigation group, focusing on issues related to valuation and solvency. Mr. Vitti has 20 years of valuation experience.

Mr. Vitti can be reached at (973) 775-8250 or by e-mail to michael.vitti@duffandphelps.com.