Using the Option Pricing Method Changes the Standard of Value

Does the IRS or Anyone Care? (Part I of II)

In part one of this two-part article, the author presents the two methods for allocating value to common stock for 409a valuations, and then show how they affect the pricing of common stock. By way of background, to meet FMV, the standard of value requires measuring value under the representation of a hypothetical willing buyer and a hypothetical willing seller, both with equal knowledge of the facts, that engage in an arm’s-length transfer. Yet, the Option Pricing Method (OPM) used to price common stock is based on a model of marketable securities. For private companies needing a 409a valuation, how is it that the OPM is used to measure their non-marketable asset? Can this method meet our Fair Market Value standard? Do we run the risk of having OPM valuations thrown out of court?

[su_pullquote align=”right”]Resources:

Review of the Standards and Premises of Value—What They Mean and When They Are Used

Business Valuation Reports and the Internal Revenue Service

Valuation of Equity Securities of Privately Held Companies

Understanding Option Valuation Theory—Valuing Employee Stock Options

[/su_pullquote]

In part one of this two-part article, we present the two methods for allocating value to common stock for 409a valuations, and then show how they affect the pricing of common stock.

Since the creation of qualifying stock options in 1981, the IRS has required that the strike price for stock options be priced at or above the fair market value (FMV) of the underlying stock to qualify as deferred compensation and avoid a taxable event. With the thrust of 409a valuations being defensibility for the IRS, FMV compliance is fundamental. So, an expert that applies the wrong standard of value can be sure that the Tax Court will disregard their valuation.

To meet FMV, the standard of value requires measuring value under the representation of a hypothetical willing buyer and a hypothetical willing seller, both with equal knowledge of the facts, that engage in an arm’s-length transfer. Yet, the Option Pricing Method (OPM) used to price common stock is based on a model of marketable securities. For private companies needing a 409a valuation, how is it that the OPM is used to measure their non-marketable asset? Can this method meet our Fair Market Value standard? Do we run the risk of having OPM valuations thrown out of court?

Stock Valuation Methodology

The first step in any common stock valuation is to value the company as of the current date. Then the classes of equity are defined and value is apportioned to these equity blocks. (We note here that some 409a valuation reports do not even employ this valuation step, but instead determine implied equity value from a single, recent round of financing.)

First Determine Fair Value

Fair Value for this purpose is the undiscounted FMV of the entire company. A FMV business valuation addresses the “current value” of a business at the valuation date. If a recent round of financing is available, of course this is used as a key benchmark, but other methods are also used to triangulate on a value—primarily the Market Approach, capitalization of cash flow and discounted cash flow. We can also add a projection of potential future exit proceeds and discount that value to present, depending on the conditions.

This baseline business valuation is based on a control interest and it defines what the entire company is worth on the valuation date. The next step is to allocate the total equity to individual classes, and this allocation by OPM is the topic of interest.

“Current Value” Allocation of Equity

After determining total equity available to the owners, establishing what each ownership class gets paid in the hypothetical sale follows. These values are found from an accounting of a company’s outstanding higher equity instruments, including:

- Conversion rights of debt instruments

- Conversion rights of higher forms equity

- Outstanding options

- Vested options

- “In the money” options on the grant date

This waterfall analysis assesses convertible notes, preferred stock(s), and restricted stock in order to determine the equity value remaining in the common stock. Waterfall analysis refers to the order in which cash proceeds from a sale are distributed to different classes of equity based on the contractual obligations of the original investment.  Traditional waterfall structure pays the convertible debt first, preferred equities next, with the common stock being valued at the excess worth over these higher priority obligations of the firm.

Common stock price is then determined by dividing its value by the number of common shares. The most common measure of share price used for option grants is based on a fully diluted value. Management policy defines whether fully diluted value includes the entire set of authorized options, or only the issued options.

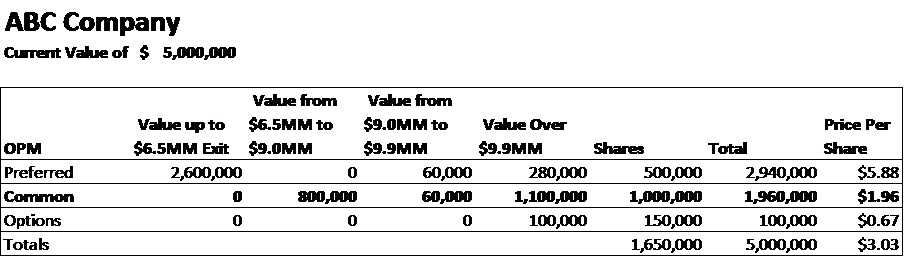

Let’s look at a simple illustration with five million dollars in equity value, preferred stock with a liquidation preference of one million dollars, and some stock options. A waterfall analysis gives:

Because the equity value is above conversion price for the preferred stock, and the options are in-the-money, all classes have value, and the diluted equity is $3.03 per share.

“But Current Value Doesn’t Capture the Future Exit Value!”

Instead of waterfall analysis, proponents of OPM suggest that a “current value” business valuation using the above method misses an element of value, so they allocate value between equity classes differently. They account for the unknowns of a future exit by using a theoretical model to fix the strike price for each equity block.

Applying probabilities from perfect market theory, OPM apportions value at the thresholds that place each equity block in-the-money. It simulates the equity structure as a combination of call options in order to capture futuristic variations of the market using the Merton-Black-Sholes differential equation (M-B-S).

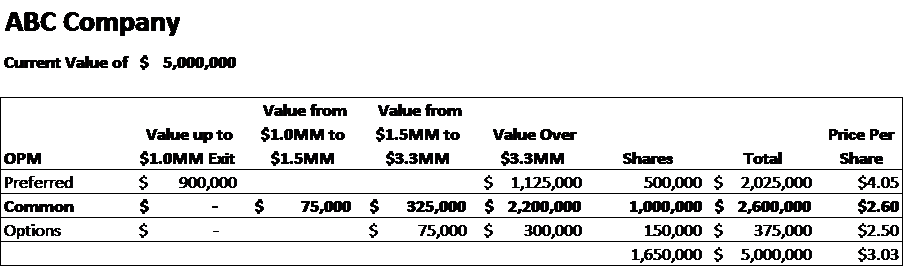

Using the ABC Company again, the participation breakpoints of value are at $1 million, $1.5 million, and $3.3 million. The preferred stock controls pay-out up to a $1 million acquisition, common stock participates above $1 million and the options participate above $1.5 million and the preferred coverts to equity at $3.3 million. An example of the M-B-S calculation results in:

The M-B-S equation back-solves for the pre-defined strike prices (break points in the waterfall) using the four key determinants of an option’s price: call price, volatility, time to expiration, and short-term (risk free) interest rate. Theses metrics come from a comparable public company selected by the valuator to represent the Subject. See that the total equity remains the same, but is simply re-allocated among classes.

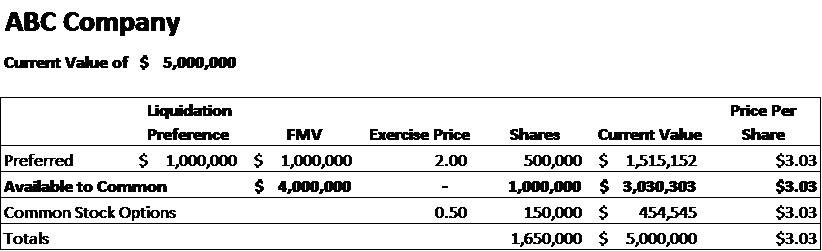

In this example, OPM reduces current value of the common stock 14% from $3.03 to $2.60. Here is a different variation where the preferred claim is greater than equity, so the common stock is underwater at the valuation date, and has zero current value. M-B-S raises the common stock value in this instance. Current value allocates equity this way:

In this case, OPM increases the current value of common stock from $0 to OPM value of $1.96.

Here is the issue: Carrying out the OPM allocation changes the stock strike value from Fair Market Value to a different standard of value—a speculative standard of value. This speculative value is based on introducing a market for the individual equities as if they could be sold in the future separate from the others. This stance switches the actual environment in which the company equities are sold to a unique market of public stocks.

False OPM Assumptions

The primary false assumption of OPM for most companies is the presumption of an exit event at a future date. This is clearly a hypothetical condition added to the problem definition, not a true circumstance.

Second, OPM switches markets. The actual market of buyers for control interests is replaced by public markets for minority interests. Public markets are unique to around 3,700 companies, and do not reflect the 30,000,000 private companies and how they transfer in a sale. Since private common shares are subject to action of the controlling shareholder(s), the characteristics of the M&A market where transfer is expected to occur are lost.

OPM then assumes a variation in possible exit values based on the liquidity of substitute minority interests. It does not address the “why” behind the size of a possible exit event; it simply applies market volatility, or trading variance. Statistically, it adjusts relative values with a log-normal probability distribution. This substitution has no identifiable connection to the company’s ability to achieve performance levels that would warrant a range of exit values.

The fourth false assumption is that by simply keeping the total equity fixed, that the result of OPM supports a FMV standard. But OPM changes this premise, and we will discuss this further.

OPM Impacts on the Valuation Problem

Implicit in OPM are a few changes to the valuation problem. Multiple conflicts exist with OPM and current valuation.

Change in Valuation Subject

Comparing discrete equity blocks relative to one another has the effect of shifting the subject of valuation from the company to the discrete classes of equity. Â OPM has the effect of de-linking the equity interests from each other as it shifts the subject of valuation to partial interests.

Applying simple probability theory separates equity classes but leaves them otherwise undifferentiated. In fact, these interests have features beyond their trading value. They are not homogenous, but have differing control capacities and ability to be sold. Some interests have strategic influence, some do not. Some have dividends, some do not. This diversity is an important value consideration. So, moving to the equity block as the subject of valuation becomes a much more complex problem than simply applying market volatility. Using a simple formula adjustment begs the question, even if it is calculus.

Shift in Valuation Date

Applying probabilities based upon a future liquidity event, moves the valuation date from the present to an arbitrary future date.

Market

Another alteration is replacement of the hypothetical FMV prudent investor having the capability to acquire the company, with a faceless market. OPM itself is an attempt to move the analysis from FMV to market value. Real transaction data for private companies is lumpy, intermittent. For most, price is stable for periods of time, not fluctuating as OPM suggests.

Common Sense

In the actual market, company sales of equity are often made to early stage angel investors and venture capital companies. These prudent, knowledgeable investors avoid common stock. They buy preferred stock with hedges against business failure, dividends, and board seats. This pattern points to a reduction in value for common stock and a premium for the preferred interests. OPM often has the opposite effect, which runs counter to common sense.

Accounting Practice

As the focus switches to the exit event, we also mismatch future values with present values. This violates accrual accounting principles. In accrual systems, revenue is recognized when it is earned. This is a foundational practice used to avoid misrepresentations. The fact is that no future value can be earned, so OPM violates core accounting principles necessary to avoid distortions of fact.

Even if we believe the equity values found with OPM are germane, the shift to equity blocks and future possibilities demands better definition and more sophisticated scrutiny than OPM alone. Once we shift to partial interests, we must also deal with other features of the securities. So, another important consideration is the type II error—the omissions of OPM.

In part two of this article, we look at OPM’s omissions, regulatory issues, setting of strike prices, and the effect on stakeholders.

James A. Lisi is a partner and valuation expert at American ValueMetrics Corporation with over twenty-five years in executive and strategic positions in Fortune 100, Private Equity and his own personally held businesses. His opinions of value are analytically sound, market based, and highly defensible—presented in formats and methodologies that are highly respected by the Tax Court and investors alike. He has been valuing businesses with American ValueMetrics for more than twelve years and is a member of the National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA), holding the Certified Valuation Analyst (CVA) designation. He is a California state-appointed member of the California Coastal Loan Committee, a member of Premier Professionals of Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara Professional Advisors, Rotary International, and the California Coast Venture Forum.

Mr. Lisi can be reached at (805) 797.1710 or by e-mail to jim@sbvaluations.com or james.lisi@americanvaluemetrics.com.