Commercial Damages and Lost Profits

Case Study of a Real Estate Developer

For most lost profits cases, the losses begin at the date of the harmful act and end when the injured party is returned to the position it would have had ‚Äúbut for‚ÄĚ the alleged damaging act of the defendant. However, not every lost profit matter is a breach of contract where beginning and ending dates can be easily defined. Sometimes losses may not occur until a period in the future. This situation requires the expert to assess the facts of the case and anticipate the market and economic environment when calculating these future losses. In this article, the author recounts the approach taken in a case where damages occurred long after the harmful act and the Daubert issues that arose in the case.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]Resources:

Commercial Damages and Lost Profits

Anticipating Daubert Challenges

Avoid the Hot Seat‚ÄĒ11 Common Pitfalls in Lost Profits and Business Damages Analysis

[/su_pullquote]

For most lost profits cases, the losses begin at the date of the harmful act and end when the injured party is returned to the position it would have had ‚Äúbut for‚ÄĚ the alleged damaging act of the defendant.¬† However, not every lost profit matter is a breach of contract where beginning and ending dates can be easily defined.¬† Sometimes losses may not occur until a period in the future.¬† This situation requires the expert to assess the facts of the case and anticipate the market and economic environment when calculating these future losses.

Regardless when the loss is to have been incurred, the expert‚Äôs approach to the loss calculation remains the same.¬† It is an assessment of lost net profits.¬† The calculation of the net lost profits is ‚Äúgenerally computed by estimating the revenues (gross and net) that would have been earned ‚Äėbut for‚Äô the alleged acts reduced by avoided costs (or incremental costs) that did not occur because of the subject lost revenues.‚ÄĚ[1]

However, it has been recognized that the calculation of lost profits for delayed loss periods creates more difficult assignments for experts.  The National Academy of Sciences reference guide for Estimating Economic Damages states:

‚ÄúProjecting lost revenues can be straightforward if the disrupted revenue stream occurs immediately following the bad act and the firm recovers relatively quickly.¬† More complex cases can arise if the effect is delayed or the recovery is slow, intermittent, or nonexistent.¬† ‚ĶThe projection of the revenue stream is likely to be the most controversial part of any damages estimate in a business case because it requires so many assumptions on the part of both experts with respect to the other players in the market and customer demand.‚ÄĚ[2]

Recently, I was involved in a matter that required making a calculation for lost profits that would have occurred long after the alleged harmful act.  This is a matter in which I prepared a report, was deposed, faced a Daubert challenge, and ultimately testified at the trial.  This article will review my process of applying standard methodology to this unique situation.

Case Facts

The plaintiff in this case was a real estate developer in the Dallas Fort Worth Texas market.¬† He had begun his career with a large residential home builder.¬† In 1987, he left his employment with this large developer/builder to begin his own developing company.¬† He would purchase raw land, subdivide the land, put in streets, utilities, and improvements, and then sell the lots to home builders or individuals who wanted to build in his development.¬† By 2006, he had developed more than 900 lots in 24 different developments in the Northeastern part of Tarrant County Texas.[3] ¬†His developments were primarily for ‚Äúluxury‚ÄĚ homes with prices of finished houses beginning in the $800,000 price range.[4]

The defendant in this case was a well-known international bank and one of its former loan officers.  In 2006, the plaintiff had five real estate projects in various stages of development.  The plaintiff borrowed money from a regional Texas bank to refinance his loans on three of these projects.  The two other projects were financed through another lending institution.  After 2006, the regional Texas bank was acquired by a national bank which ultimately merged with a larger international bank.

By the beginning of the great recession in 2008, the plaintiff had sold more than fifty percent of the lots in two of the developments and approximately one third of the lots in the other that had refinanced through the defendant.

Between 2006 and 2009, the plaintiff sought several extensions on these loans.  The bank agreed to these extensions until December 2009.  While negotiating the December 2009 extension, the bank loan officer assured the plaintiff his loans would be renewed and extended.  However, at that same time, the bank was negotiating to sell the loans to a national builder.

In January 2010, the plaintiff’s loans were sold to this national builder who demanded payment along with default interest payments.  In April 2010, the national builder foreclosed on all three developments and the three entities representing the plaintiff’s three developments went into bankruptcy.[5]

The properties were taken by the national builder via foreclosure and/or credit bid at the bankruptcy hearing.  Through this process, the defendant maintained a default claim against the plaintiff.  The plaintiff then sued the bank and loan officer for fraud.[6]

A series of trials and appeals began.  Ultimately, the case was returned for trial.  However, due to Texas law and an appellant court ruling, the plaintiff could not argue for lost profits from the three developments whose loans had been purchased.  Only claims for out of pocket expenses could be made.  Legal interpretations of the appellant court’s ruling said lost profits from development projects that would have been started and completed after the foreclosure on the three properties could be included in the out of pocket expenses.

I was hired in 2016 to estimate lost profits for the projects that had not occurred since the foreclosure in 2010.  After the foreclosure, the plaintiff had not begun a single development.  He had not pursued any projects because of his developments’ bankruptcies and the multimillion dollar default claims that had been made against him.

It became my assignment to determine what he would have done developing properties in Tarrant County, Texas were it not for the alleged harmful act of the bank officer and the bank.[7]

Analysis

Thousands of pages of documents were exchanged between the opposing sides.  Most helpful in assessing future profitability were credit reports prepared by three banks from 2006 through 2009.  One of the banks was not involved in the lawsuit.  It had made a loan on one of the other two projects being developed by the plaintiff in 2006.  The other two banks preparing the credit reports were affiliated.  One credit report was for the initial refinancing of the loans in 2006, when the lender was a regional Texas bank.  The second report was for one of the extensions of the loans after the bank had been purchased by a national bank.

These reports provided great insight as to the lenders’ research, analysis, and confidence in the plaintiff’s ability to profit from his developments and repay his loans.  They also contained projections provided by the plaintiff as to the ongoing sale of the lots in the developments covered by these loans.  These projections ultimately played a prominent role in my calculations.

After reviewing the initial data, I met with the plaintiff.  This meeting gave me an opportunity to not only better understand how the plaintiff’s operations worked, but also understand his investor group and borrowing philosophy.  We were able to discuss his plans after the completion and selling of the developments in question and when he planned to retire.

This meeting led to another exchange of financial documents and research on real estate lot availability in the market served by the plaintiff.  Much of the real estate data were gathered and maintained by one of the plaintiff’s real estate partners.

After reviewing this new data, I again met with the plaintiff.¬† At this meeting, I was able to ‚Äúfine tune‚ÄĚ my analysis, focusing on data to be used in assessing the profits from future developments.¬† I also spoke with the plaintiff about how he profited from his developments.

After our second meeting, I spoke with the plaintiff on several occasions by telephone to clarify information.  By the end of this series of meeting and phone calls, I had a clear vision of how the plaintiff’s operations had worked.

Historically, the plaintiff would find a piece of raw land that fit in the plaintiff’s parameters for a residential development.  He would negotiate a purchase price and make an earnest money payment to hold the land.  The plaintiff would then contact a group of investors with whom he had worked for several years to solicit money to purchase the land.  As many as ten to fifteen investors would participate in any one development.  Several of the investors were limited partners in all his developments.  But, some names would change from project to project.

With investors on board and after using their money to purchase the land, the plaintiff would go to a bank and borrow funds to develop the property; platting and zoning the land then putting in water, sewer, utilities, streets, bridges, fountains, and trees.  Under normal circumstances, lots would be sold as the development was completed.  The first 70% of the lots sold repaid the loan (principal and interest) and covered expenses incurred for maintaining and managing the property.  The plaintiff owned a management firm that was the general partner for each project.  Through the general partner, he received a salary for managing the development.

Investors (including the plaintiff) were paid for their limited partnership interests from the proceeds of the remaining 30% of the lots.  The plaintiff, through several limited partnerships and family trusts, held 42.5% of the limited partnership interest in his developments.

This historical pattern of purchase the land, develop it, sell the lots and then move to the next project did not hold true during the great recession.  All five of the plaintiff’s developments suffered financial problems.  For one development, he was able to sell the lots to another developer/builder.  In another, he arranged for an investor to purchase the plaintiff’s loan from the bank and ultimately take control of the developed lots.  With those situations managed, that left the three loans that were the center of this lawsuit.

The plaintiff argued, if the bank had not deceived him, he could have planned for other investors to either purchase the loans or the lots.  However, when the bank sold the loans to the national builder, the new owner did not want to sell, but agreed it would only if the principal and default interest at a rate of 18% were paid.  It was the accumulation of this default interest that greatly increased the size of the default claims.

Researching External Causality

After considering this information, I recommended a loss period from 2010 through 2017.  This placed the loss period after the alleged harmful act but not immediately thereafter.  While eight years in length, the loss period only provided for a short period of loss in the future for which any discounting to present value would be required.[8]  The plaintiff and his attorneys agreed with my recommendation.  So, I moved forward by assessing outside influences which may have impacted the success or failure of residential real estate developments during the loss period.

My review began with publications from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas that focused on the state and more importantly, the Dallas Fort Worth market.  Texas and the Dallas Fort Worth area came out of the recession in late 2010.  The Dallas Fort Worth area had constant growth early in the loss period.  Oil prices were very high at that time.  This fueled some of the growth, more so in Texas than in the Dallas Fort Worth area.

In 2014, oil prices began a precipitous decline.  Houston, Midland, Odessa, and several other Texas cities were greatly impacted by this.  Because of the diversification of industries in the Dallas Fort Worth area, their local economy continued to expand.  By the end of the loss period, the Dallas Fort Worth market had outperformed all of Texas.

Additional research was made into the micro market served by the plaintiff’s developments.  This area was called the Grapevine Colleyville area.  The plaintiff worked, almost exclusively, in Colleyville.  For this research, I relied on local newspaper and magazine articles discussing development in that area, Chamber of Commerce information, and the Fitch Ratings report on Colleyville.[9]  I also relied on data found in three appraisals (one for each project) purchased in 2009 by the bank for assessing the value of its collateral for the three loans.

All the data pointed to continued growth during the projected loss period.  The data specifically supported growth in the Colleyville area which had been the location of the plaintiff’s most recent five developments.

This information was used for the early sections of my report.  It highlighted the good economic climate during the loss period.  This was an effort to reduce any concern that outside economic factors would have prevented the plaintiff from moving forward with new projects.

Lost Profits Calculations

The lost profit analysis was pieced together with data from the bank credit reports and the plaintiff’s future profit projections that had been provided to the bank in 2006 as a part of their credit analysis.

The plaintiff’s projections were critical.  In 2006, there was no concern of the recession that would begin in 2008.  The plaintiff’s calculations were based on his years of experience and his anticipation of an expanding market.  The market for selling lots in 2006 was like the economic environment found in the Colleyville area from 2010 through 2017.  Therefore, I relied on the plaintiff’s expertise in the real estate development field, which had been well noted and praised in the bank credit reports, to supply a basis for the profits to be generated by future projects.  This was the argument made to the court and the jury for relying on the plaintiff’s projections.

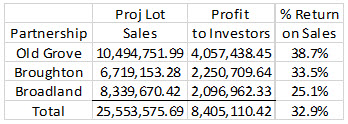

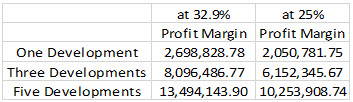

A review of these projections provided the following profit to investors:[10]

For my initial calculations, the average return to investors of 32.9% was used in determining lost profits.

In our meetings, the plaintiff had said he assumed a minimum 25% profit margin when making his projections.  He stated this was the minimum profit margin acceptable to lenders.  Although he testified of profit margins greater than 25%, the 25% profit margin was used for a second set of calculations which provided a range of lost profits.

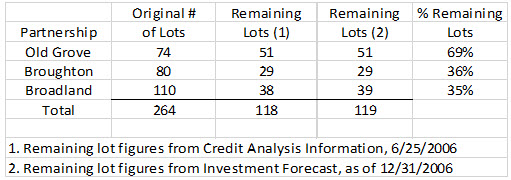

The anticipated lot sales from the 2006 projections reflected only the remaining lots at the time of refinancing.  A review of the bank credit reports showed the following historical data:

The variance of one lot in Broadland did not affect the percentage remaining figure.

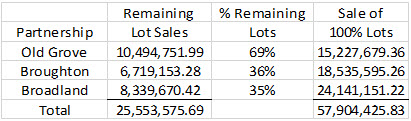

Because the developments during the loss period would be total developments and not partial, the development values were increased to reflect full developments.  That calculation appeared this way:

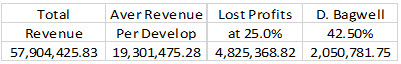

Based on this data, the average revenue per development was determined.  When the total 100% lot sales were divided by three, the average revenue per development was $19,301,475.28.  To this revenue amount, the 32.9% and 25% profit margins were applied.  This provided the profits for all investors.  The plaintiff had 42.5% ownership of the limited partnership and therefore received 42.5% of the profit distribution.  The calculation of his share of the lost profits was presented this way to the jury.

At 32.9% profit margin:

At 25.0% profit margin:

These figures showed losses based on 2006 market values.  No adjustment was made to these loss figures for increased pricing during the loss period.  During the recession, the value of lots declined in 2009 and 2010.  Although some price inflation could be expected, research was not performed to determine when lot prices grew to exceed 2006 values during the loss period.

Because the plaintiff had five projects in various stages of completion at the time of the 2010 foreclosures, the lost profits calculations assumed he could have started and completed between one and five developments during the loss period.  The jury was provided with data for the plaintiff’s estimated lost profits from not being able to begin and complete one development, three developments, and five developments.  This data was presented this way:

Daubert Challenge

In Texas courts, a Daubert challenge is called a Robinson challenge.¬† The Robinson case calls for the Daubert standards to be applied in Texas court cases.[11] ¬†Judges vary in wanting ‚Äúlive‚ÄĚ hearings to listen to the expert‚Äôs testimony and cross-examination or written arguments through affidavits before ruling on such a motion.

In this case, the judge asked for written motions, responses, and affidavits.  My affidavit was thirteen pages.  It contained a long review of my report and paragraphs responding to specific points in the defendant’s motion.  After reviewing all the pertinent information, the judge denied the defendant’s motion thus allowing me to testify.

Jury Verdict

The Dallas County jury was well aware of the economic growth in the Dallas Fort Worth metroplex from 2010 through 2017.  They were also aware of the growth in the Colleyville area.  I believe this greatly helped in their understanding the basis for the lost profits calculations.

The jury found in favor of the plaintiff.  They awarded the lost profits at the five developments level with a 32.9% profit margin.  They also awarded damages for additional claims made by the plaintiff.  The damages awarded by the jury were substantial and the defendant has appealed.

Conclusion

This case presented a unique situation for assessing lost profits.  Because of appellant court rulings, lost profits for the three developments related to the loans that brought about the lawsuit could not be considered.  Although the plaintiff’s business had been destroyed, a business destruction valuation was not appropriate.

This was because each development was its own business through a limited partnership.  These limited partnerships were not begun to be long running businesses, but short-term entities alive only long enough to represent one specific real estate development before all the lots were sold.

The plaintiff’s ownership was through his management company that was the limited partnership’s general partner and several limited partnerships and family trusts that owned 42.5% of the limited partnership.  By default, it appeared lost profits was the best way to estimate the plaintiff’s losses.

Communication among the plaintiff, his attorneys, and the expert allowed for a clear understanding of the assumed loss period, data needed for determining lost revenue, and lost profit margins as well as the loss specific to the plaintiff.  It was only through the series of meetings and phone calls this information could be found, examined, and clarified.

This case was time consuming but rewarding.  At trial, the witnesses testifying prior to my testimony laid a solid foundation on which to build my calculations.  Without spending such time with the attorneys and plaintiff, the teamwork in telling the plaintiff’s loss story would not have been possible.

As with any case, an expert can meet the challenge of estimating commercial damages only through good communication, requesting and reviewing critical data, and sharing with attorneys and their client opinions and concerns about the damages model.  Maintaining such open communication will allow an expert to work at his or her optimum level in providing services in any matter.  Following this process should earn the expert respect in the market he or she is striving to serve.

[1] The Comprehensive Guide to Lost Profits and Other Commercial Damages, 3rd Edition, Vol. 1, Nancy Fannon, Jonathan Dunitz, BVR, 2014, page 210.

[2] Ibid, page 500.

[3] Tarrant County is part of the Dallas Fort Worth metroplex market.

[4] A home in this price range would have been considered an upper end, luxury home in the Dallas Fort Worth area at that time.

[5] Limited partnerships had been created for each development.  Therefore, each entity was a stand-alone project.

[6] David Bagwell, et al., v. BBVA Compass and Sam Meade; Marilyn Gardner, Chapter 7 Trustee, et al., Intervening Plaintiffs v. BBVA Compass and Sam Meade, Cause DC-14-00991, Dallas County Texas.

[7] Fort Worth is the county seat for Tarrant County.  Dallas is the county seat for Dallas County.  These two cities are the largest in the Dallas Fort Worth metroplex.

[8] Ultimately, the trial took place in December 2017.  Because the end of 2017 was the close of the projected loss period, no discounting was needed.

[9] Fitch is one of the big three risk ratings companies in the U.S.  Standard & Poors and A.M. Best are the other two.  Fitch provided an analysis of Colleyville in conjunction with the town’s municipal bond offering.

[10] The three limited partnerships show in the Partnership column represent the limited partnership for each of the developments.

[11] E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co v. Robinson, 923 S.W.2d 549 (Tex. 1996).

Allyn Needham, PhD, CEA is a partner at Shipp Needham Economic Analysis, LLC, a Fort Worth based litigation support and economic consulting firm. He has worked as an expert in litigious matters for more than twenty years. Prior to that, he worked in the banking, finance, and insurance industries. As a testifying witness, Dr. Needham has testified on matters relating to lost profits, business valuation, personal damages, and business bankruptcy. Dr. Needham has published articles in the areas of financial and forensic economics and provided continuing education presentations at economic, vocational rehabilitation, and bar association meetings.

Dr. Needham can be contacted at (817) 348-0213, or by e-mail to aneedham@shippneedham.com.