Residency and Domicile Determinations

for State Income Tax Purposes

How will the SALT limits impact growth? Demographic trends? In this article, the author looks at current data, considers these issues and other tax matters that complicate residency choices and options.

A few years ago Fox News Channel’s commentator and nationally syndicated radio talk show host (both based in New York), Sean Hannity, threatened that he was going to leave New York, a high personal income tax state, for Florida and Texas, no personal income tax states…and that was when there was a full federal itemized deduction for state and local income taxes, state and local property taxes, and sales taxes (SALT). The 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA) limits the SALT deduction to an amount not exceeding $10,000.

The limitation of the SALT deduction is quite controversial and had faced strong resistance from Congressmen representing California, Connecticut, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Nebraska, New York, New Jersey, Vermont, and Wisconsin, who had argued that their states could see a mass exodus of business and employees. That anticipated mass exodus eventuality could substantially reduce state tax revenues and cause concern about their ability to pay the interest and principal on their outstanding Municipal Bond issuances and limit the market for new issues. The Municipal Bond markets could become chaotic.

As noted above, capping the SALT deduction at $10,000 and severely limiting mortgage interest deductions (for one qualified residence and one additional residence) to a $750,000 maximum mortgage on which interest is deductible could have a material adverse effect on the housing market in general—particularly in the high tax states in the northeastern region, the west coast (particularly California) and portions of Oregon, and western Washington State (Pierce and King County), as well as the “rust belt.”

University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) economist and professor in the Department of Public Policy, Michael Stoll, avers that, “The data collected by United Van Lines aligns with longer-term migration patterns to southern and western states, trends driven by factors like job growth, lower costs of living, state budgetary challenges, and more temperate climates…Unlike a few decades ago, retirees are leaving California, instead, choosing other states in the Pacific Northwest and Mountain West. We’re also seeing young professionals migrating to vibrant, metropolitan economies, like Washington, D.C. and Seattle.”

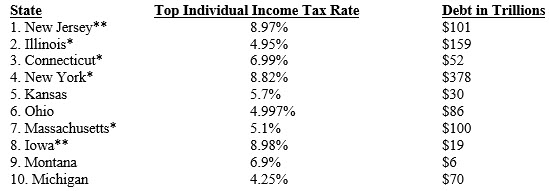

Here are the top ten states, ranked in order, experiencing a net decline in population:

*imposes an estate tax; **imposes an inheritance taxi mposes an estate tax; **imposes an inheritance tax

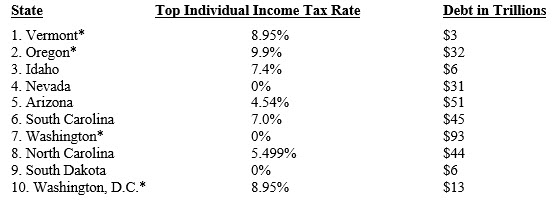

Here are the top ten states, ranked in order, experiencing a net increase in population:

*imposes an estate tax

Three of the above top ten inbound population states have a 0% income tax rate; this may indicate a growing population exodus from high (6% +) personal income tax rate states:

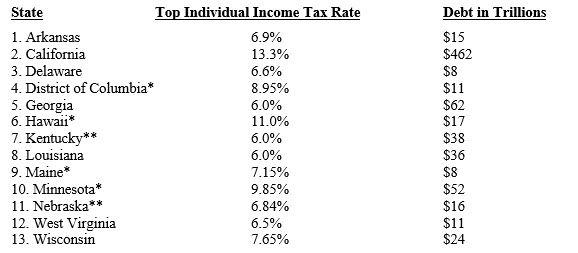

*imposes an estate tax; **imposes an inheritance tax

Many cities and other local jurisdictions also have an income tax that must be paid in addition to the federal and state tax levies. e.g., New York City imposes a personal income tax rate up to 3.876% in addition to the state levy.

According to ATTOM Data Solutions, https://www.attomdata.com/data/, U.S. homeowners paid property taxes of some $278 billion in 2016; on average, each of the country’s 84 million single-family homeowners paid an effective 1.15% tax rate on the “full fair market/appraised” value of their residence or about $3,300 in property taxes. Thirty-two of the 586 total counties collected annual property taxes averaging $7,000 or more. According to the report, there were nine counties in the country with a population of at least 100,000 that had average annual property taxes of more than the SALT federal deductibility limit of $10,000: Westchester, Rockland, and Nassau counties in New York; Essex, Bergen, Union, and Morris counties in New Jersey; Marin County, California; and Fairfield County, Connecticut.

Alaska (no state sales tax imposition but cities and localities may impose such taxes [1.89% top rate in 2018]) Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon are the only five U.S. states that do not impose “sales” and/or sales and use taxes. The 45 states and Washington, D.C. that do impose such taxes (there are roughly 10,000 sales tax jurisdictions in the U.S.) have, in general, extraordinarily complex and near indecipherable rules and regulations. New York, for example has this as an explanation for its imposts: “Sales of tangible personal property are subject to New York sales tax unless they are specifically exempt. Sales of services are generally exempt from New York sales tax unless they are specifically taxable.” The five states with the highest combined state and local sales tax rates are: Arkansas (11.5%); Louisiana (11.45%); Alabama (11%); Washington (10.4%); and Tennessee (9.25%).

Among major cities, Long Beach (3%), California (7.25%) [total 10.25%], and Chicago (4%), Illinois (6.25%) [total 10.25%], impose the highest combined state and local sales tax rates; they are closely followed by Montgomery (6%), Alabama (4%) [total 10%], and Baton Rouge and New Orleans (5%), Louisiana (4.45%) [totals 9.45%].

Business entities that are “online” sellers of goods and services conceivably must comply with sales tax laws in the 45 states and Washington, D.C. having sales tax laws—and with the local jurisdictions who may impose additional levy on additional products as well. It had long been argued that invoicing for and collecting and remitting the sales tax impositions was an extraordinary burden that must be shouldered by online sellers of goods and services that have a physical presence or other nexus (connection) in the sales tax imposing jurisdiction.

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) in Quill Corp. v. North Dakota, 504 U.S. 298 (1992) asked Congress to find a solution to the problem of sales taxing remote sales from retail purchases made over the Internet or other e-commerce means unless the seller had a physical presence in the sales taxing state jurisdiction. The Quill Corp. decision effectively prevented states from interfering with interstate commerce by preventing states from collecting sales tax unless authorized by the United States Congress.

The Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 made permanent the ban on federal, state, and local taxation of e-mail and internet access originally enacted in the 1998 Internet Tax Freedom Act. Title XI of Pubic Law (PL) 105–277.

The Marketplace Fairness Act of 2017 (MFA), introduced in the Senate on April 27, 2017, would have authorized each member state under the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement (the multistate agreement for the administration and collection of sales and use taxes adopted on November 12, 2002) to require all sellers not qualifying for a small-seller exception (applicable to sellers with annual gross receipts in total U.S. remote sales not exceeding $1 million) to collect and remit sales and use taxes with respect to remote sales under provisions of the agreement, but only if such agreement included minimum simplification requirements relating to the administration of the tax, audits, and streamlined filing.

The bill defined “remote sale” as a sale of goods or services into a state in which the seller would not legally be required to pay, collect, or remit state or local sales and use taxes unless provided by the bill. The bill also prohibited states from beginning to exercise the authority granted by the bill for a specified period after enactment.

The Remote Transactions Parity Act of 2017 (RTPA) was introduced in the House of Representatives on April 27, 2017. This Bill provided that each Member State under the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement was authorized, notwithstanding any other provision of law, to require all remote sellers not qualifying for the small remote seller exception to collect and remit sales and use taxes with respect to remote sales sourced to that Member State pursuant to the provisions of the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement, but only if any changes to the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement made after the date of enactment of the Act, were not in conflict with specified minimum simplification requirements. A state could exercise authority under this Act on the first day of a month beginning 180 days after the state published notice of the state’s intent to exercise the authority under the Act, but no earlier than the date provided in the Bill.

Both the MFA and the RTPA legislative proposals would have allowed states to require sellers not having any physical presence or other nexus to the sales taxing jurisdiction to collect sales taxes on online and catalog sales delivered to residents within their borders.

SCOTUS in South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc., 585 U.S. (2018), argued on April 17, 2018, and decided June 21, 2018, is a case in which the Court held by a five to four majority that states may charge tax on purchases made from out-of-state sellers, even if the seller does not have a physical presence in the taxing state. The five justice majority decision overturned Quill Corp. v. North Dakota (1992), which had held that the Dormant Commerce Clause (an inferred restriction prohibiting a state from passing legislation that improperly discriminates against interstate commerce) barred states from compelling retailers to collect sales or use taxes in connection with mail order or Internet sales made to their residents unless those retailers have a physical presence in the taxing state. The majority opined that the physical presence rule decided in Quill Corp. v. North Dakota was “unsound and incorrect” in the current age of Internet services.

As noted above, both the MFA and the RTPA legislative proposals have been languishing in Congress in one form or another for more than twenty years. Will Congress now awaken to the serious economic consequences of South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc., and pass any federal legislation? Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) believes that the federal government should wait for the states to act before acting on online sales tax legislation. Durbin opines that, “As far as I’m concerned—I can’t speak for anyone else—this notion of preempting the states at this point I think is a serious mistake…We tried for years, literally for years, to set a federal standard here and all of the people who are squawking and screaming now about the Supreme Court decision resisted.”

Congress seems, at best, reluctant to propose, debate, and pass any federal legislation to provide taxpayers with guidance and certainty in this grave matter of the taxation of interstate commerce. It seems that the sales tax revenue opportunities for states has provided them with the impetus to move forward with remote seller legislation at a lightning fast clip.

So, as can be seen, although we have the South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc., decision from SCOTUS, many questions remain. A great number of states have already enacted laws, generally with an October 1, 2018 effective date, to require online sellers to collect sales tax even where there is no physical presence or other nexus to the state. Several other states are either considering or are in the process of enacting such laws.

As various levels of government try to figure about what the South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc., online interstate sales tax decision looks like in practice, it leaves a lot of uncertainty for sellers and their accountants on how to move forward.

As noted earlier, the 2017 TCJA $10,000 limit on federal income tax deductions for state and local income taxes, sales taxes, and property taxes has state and local taxing authorities scrambling to reset their tax policies with an eye toward preserving their business and individual tax base, raising sufficient revenues to maintain operations, and pay for the interest and principal payments due on their outstanding Municipal Bond obligations. A rising federal deficit may further complicate the prospect of future federal tax relief.

On January 26, 2018, New York Governor, Andrew Cuomo, announced the formation of a coalition with New Jersey and Connecticut (now joined by Maryland) to sue the federal government and challenge the TCJA limitation on the deductibility of SALT to $10,000. The New York average SALT deduction in 2015 was $22,169; the New Jersey average SALT deduction in 2015 was $17,850; the Connecticut average SALT deduction in 2015 was $19,665; and the Maryland average SALT deduction in 2015 was $12,931. (California average SALT deduct in 2015 was $18,438.)

The cause for action is the argument that TCJA “preempts the states’ ability to govern by reducing the ability to provide for their own citizens, and unfairly targets New York and similarly situated states in violation of the Constitution.”

The lawsuit follows on the heels of Governor Cuomo’s (former California Governor, Jerry Brown, has floated similar ideas) proposals to have citizens make “charitable contributions” for governmentally provided goods and services.

Recharacterizing personal income taxes as “charitable contributions” is one idea, another is repealing the personal income tax and imposing a flat “payroll tax” on the employers.

New York Governor Cuomo’s proposals, however, are fatally flawed. It is well established law that a “payment of money generally cannot constitute a charitable contribution if the contributor expects a substantial benefit in return.” United States v. American Bar Endowment, 477 U.S. 105, 116-17 (1986). Generally, where some benefit is received in return, “[t]he taxpayer…must at a minimum demonstrate that he purposefully contributed money or property in excess of the value of any benefit he received in return.”

Internal Revenue Code Regulations Section 1.170A-1(h) provides that no portion of the payment in consideration for goods or services is a contribution or gift unless the taxpayer can prove that he or she: 1) intends to make a payment in an amount that exceeds the fair market value of the goods or services; and 2) actually makes such a payment. A gift is a transfer that: 1) is voluntary, and 2) is motivated by a “detached and disinterested generosity.” Commissioner v. Duberstein, 363 U.S. 278, 285 (1960). Rev. Rul. 86-63, 1986-1 C.B. 88 provides that, “Where consideration in the form of substantial privileges or benefits is received in connection with payments by patrons of fund-raising activities, there is a presumption that the payments are not gifts.”

Another untenable proposal of New York Governor Cuomo would have a “payroll tax” supplant the state income tax—a flat rate of tax on the employer to replace a graduated income tax rate on “net” taxable income of the employee. However, New York Senate Republican Majority Leader, John Flanagan, said, “Just the notion of a payroll tax scares me…I don’t see an appetite for doing something like that.”

The “charitable contribution” ploy is clearly not legitimate, and the payroll tax idea is incredibly complex in implementation and not even legislatively supported.

U.S. Census records show more than one million people moved out of the New York area to other parts of the country since 2010, a rate of 4.4 percent—the highest negative net migration rate among the nation’s large population centers.

On January 14, New York Governor, Andrew M. Cuomo, said that New York could raise about $300 million in annual revenue from the taxation of recreational marijuana and that he would propose a regulatory framework as part of his January 15 budget initiatives. However, the New York Governor may have to learn a hard lesson from the state of California where the sale of recreational marijuana has been legal for a little longer than a year now. The Los Angeles Times reports that retailers and growers have been hampered by a complex system of regulations, high taxes, and the large number of cities within the state that have decided to outright ban marijuana/cannabis retail operations. As a result of regulatory compliance costs and high taxes with the resultant high retail cost, it seems that many recreational marijuana/cannabis users continue to patronize the unregulated and untaxed illicit marketplace.

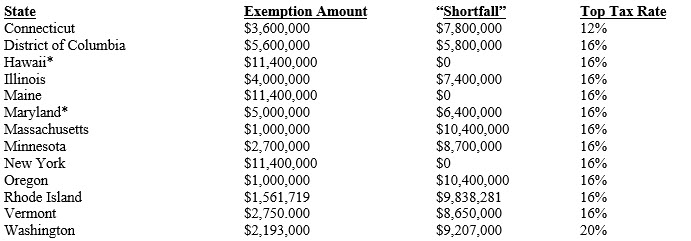

However, even if the impact of the SALT limitation can be attenuated and taxpayers assuaged, it remains of paramount importance to also note and plan for, if necessary, the fact that as of January 1, 2019, eighteen states and the District of Columbia impose an estate tax, an inheritance tax (sometimes collectively called death taxes), and/or both. Consequently, prudence dictates that it is imperative to plan for state “death tax” exposure as well as for federal transfer tax purposes. In most states that collect “death taxes” there is a significant shortfall between the 2019 federal estate tax exemption of $11.4 million ($22.8 million for marrieds) and the state estate tax exemption.

In the states imposing “death taxes” planning is problematic because the wills and trusts of residents, as well as nonresidents who own real estate in these states, must recognize that there may well be a significant difference between the federal and state exemption amounts. Additionally, it must be recognized that federal estate tax law allows “portability” (a surviving spouse may use unused portions of the deceased spouse’s exemption amount) whereas estate tax exemptions are generally not “portable” between married couples in states imposing “death taxes.”

Iowa (15%), Kentucky (16%), Maryland (10%), Nebraska (18%), New Jersey (16%), and Pennsylvania (15%) impose an Inheritance Tax in 2019—the tax is imposed only on estate assets that pass to someone who is subject to the inheritance tax. Surviving spouses are completely exempt from the tax. Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, and New Jersey completely exempt transfers to surviving children and grandchildren. Nebraska and Pennsylvania subject property that passes to children, grandchildren, brothers, sisters, nieces, nephews, and/or friends to their inheritance taxes.

States, along with the District of Columbia (D.C.) imposing an Estate tax in 2019 are:

(*provides for exemption portability)

Here is a simple and straightforward example that will illustrate the need for domicile planning: assume a single Connecticut state resident/domiciliary dies on January 31, 2019 with an adjusted gross estate of $11,400,000. Applying the federal exemption amount results in a taxable estate of $0 and therefore no federal estate tax is imposed. Applying the Connecticut exemption of $3,600,000 results in a taxable estate of $7,800,000 and a Connecticut estate tax of $842,400.

Here is a not so simple and straightforward example that will illustrate the need for domicile planning: assume a widowed Connecticut resident/domiciliary dies on January 31, 2019 with an adjusted gross estate of $22,800,000 and that the previously deceased spouse had no taxable estate assets and did not use their unified credit. As we will see later in this discussion, for federal estate tax purposes, decedents dying in 2019 and thereafter, the surviving spouse is entitled to the unused unified credit of the previously deceased spouse. There is no portability concept for the Connecticut unified credit amount.

Applying the federal exemption amount $22,800,000 (total of both unified credits) results in a taxable estate of $0 and therefore no federal estate tax is imposed. For Connecticut, on the other hand, applying the allowable exemption of only $3,600,000 (there is no portability of the previous decedent’s credit amount) results in a taxable estate of $19,200,000 and a Connecticut estate tax of $2,764,800.

What follows is a brief overview of the various determinants used in establishing one’s residency status for state income tax purposes. Residency and domicile are generally factual determinations arrived at after considering all the facts and circumstances unique to each taxpayer. The discussion is limited to the rules and policies of New York.

It is noted at the outset that the determination of one’s “principal residence” for purposes of the statutory exclusion of $250,000 ($500,000 for married taxpayer’s filing jointly) provided in Internal Revenue Code §121 may be of critical consideration before one seeks to change one’s state of residence. Additionally, it must be noted that relocation costs and “moving expense” deductions that were previously allowable are now repealed by TCJA and are no longer allowable for federal income tax purposes.

New York State Tax Law at §601 imposes a personal income tax on “resident individuals” as that term is defined at §601(1) as someone:

(a) who is domiciled in this state, unless he maintains no permanent place of abode in this state, maintains a permanent place of abode elsewhere, and spends in the aggregate not more than 30 days of the taxable year in this state, or

(b) who is not domiciled in this state but maintains a permanent place of abode in this state and spends in the aggregate more than 183 days of the taxable year in New York.

The definition of “resident” for New York City income tax purposes, pursuant to the New York City Administrative Code §11-1705(b), is identical to that for state income tax purposes, substituting the term “city” for “state.”

The significance of classification of “resident” versus “non-resident” is non-residents are income taxed only on their income sourced or derived from New York sources and only estate on their property sited within New York whereas residents are income taxed on their income derived from all sources and estate taxed on all of their estate.

Domicile means the place where one has one’s true, fixed, permanent home and principal living establishment, and to which, whenever they are absent, they intend to return.

Residency is defined as the location of one’s main home. It is where one returns when one comes back from vacation or from a temporary job or business trip. It is where one holds a valid driver’s license, where one’s mail is sent, where one’s immediate family lives, where one enrolls one’s children in school, and where one is registered to vote. The preponderance of connections to a place determines the state of residency.

The size of one’s house or its comparative fair market value may not be determinative of domicile or residency. For example, one could own a substantial house in a resort or vacation community and use it only “in season” and then as a residence used to facilitate entertainment of friends, clients, and other business associates. The New York State Department of Taxation and Finance has issued a personal income tax advisory opinion (TSB-A-11(5)(I) holding that a taxpayer who occupied a summer beach community home in a Cooperative Association pursuant to a proprietary lease from the Association, having no heating system in place and the use of which was limited by Association rules to a five-month period, did not maintain the co-op as a “permanent place of abode” for “substantially all of the taxable year.” The taxpayer was not considered a statutory resident of New York merely by virtue of his proprietary lease of the summer home.

Often, one may have to prove one’s residency in order to avoid taxation of the same income in multiple states. Here, however, “double” taxation is generally avoided because of an allowance of a credit for taxes paid to other jurisdictions. Although there may be some duplication of taxes imposed, the general effect is that one’s income is taxed at the highest state rate. If there are enough factors to cause one to be deemed resident in more than one state, it would be prudent to assemble enough evidence to be considered a resident in the state that will give one the best tax advantage. (Car registration; voter registration; voting by absentee ballot, if necessary; purchase of property and payment of property taxes; establishment of a bank account; joining a local church or a civic or business organization, etc., are all used as indicia of one’s intention of residency.)

If a taxpayer has two homes and lives in both, the main home is ordinarily the one lived in most of the time. Other factors, however, are relevant in determining which home is the principal residence. Those factors include: place of employment; location of family members’ main home; mailing address used for bills and correspondence; the address listed on your Federal and state income tax returns; the address listed on your driver’s license; the address listed on your car registration; the address listed on your voter registration card; the location of banks used; the location of the taxpayer’s recreational clubs and religious organizations, etc.

Generally, each state may have its own determination of residency for tax purposes. In the state of New York, residence is usually determined by the place where one has the closest ties in comparison with one’s ties elsewhere. In using these factors, it is the strength of the ties, not just the number of those ties that determines residency. A partial list of the factors considered are: amount of time spent in the state versus the amount of time spent out of the state (states like New York deem one to be a permanent resident if more than six months, 183 days per calendar year of physical presence is established); location of spouse and children; location of the principal residence; where the driver’s license was issued; where the vehicles are registered; where professional licenses are maintained; where one is registered to vote; the location of the bank branch holding accounts; the location of doctors, dentists, accountants, and attorneys; the location of the church, temple, or mosque, professional associations, or social and country clubs in which one maintains “resident” memberships; the physical location of real property and investments; and the location of significant social ties.

Residence then is primarily a state of mind as evidenced by one’s actions and by one’s physical presence during a taxable year.

Each taxpayer’s case is different and careful planning and recordkeeping are essential to achieve the residency objective.

James P. Crumlish is a Certified Public Accountant and Chartered Global Management Accountant with offices in Westhampton Beach, NY. He is a business consultant and provides tax and auditing services.

Mr. Crumlish can be contacted at (212) 996-3788 or by e-mail to jamespcrumlish@gmail.com.

© COPYRIGHT 2019 by James P. Crumlish, C.P.A., C.G.M.A and NACVA/CTI. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recorded, or otherwise, without prior written permission from James P. Crumlish, C.P.A., C.G.M.A., the publisher. Protected by U.S. Copyright Law (Title 17 U.S.C. §Section 101 et seq. Title 18 U.S.C. §2319): Infringements can be punishable by up to five (5) years in prison and $250,000 in fines.

The information contained in this article is provided solely for educational and informational purposes and are not presented for the purpose of providing legal advice. The views expressed do not constitute legal advice. The referenced information and exhibits are not the same as legal advice, i.e., the application of law to an individual’s specific set of facts and circumstances. It is recommended that you consult a qualified attorney for assurance that the information and exhibits contained herein, and your interpretation of same, are appropriate to your specific set of facts and circumstances.

Any accounting, business or tax advice contained in this communication, including attachments and enclosures, is not intended as a thorough, in-depth analysis of specific issues, nor a substitute for a formal opinion, nor is it sufficient to avoid tax-related penalties. If desired, James P. Crumlish, CPAs would be pleased to perform the requisite research and provide you with a detailed written analysis. Such an engagement may be the subject of a separate engagement letter that would define the scope and limits of the desired consultation services.