Fair Market Value Considerations for Rural Health Clinics

Reimbursement Environment (Part III of V)

The U.S. government is the largest payor of medical costs, through Medicare and Medicaid, and has a strong influence on healthcare reimbursement. In 2017, Medicare and Medicaid accounted for an estimated $705.9 billion and $581.9 billion in healthcare spending, respectively. The prevalence of these public payors in the healthcare marketplace often results in their acting as a price setter and being used as a benchmark for private reimbursement rates. This is particularly true for RHCs, which tend to serve a disproportionately large Medicare population. This third installment in the five-part series on RHCs will focus on the RHC reimbursement environment.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]Resources:

Fair Market Value Considerations for Rural Health Clinics (Part I of V)

Fair Market Value Considerations for Rural Health Clinics Competition (Part II of V)

[/su_pullquote]

The U.S. government is the largest payor of medical costs, through Medicare and Medicaid, and has a strong influence on healthcare reimbursement. In 2017, Medicare and Medicaid accounted for an estimated $705.9 billion and $581.9 billion in healthcare spending, respectively.[i] The prevalence of these public payors in the healthcare marketplace often results in their acting as a price setter, and being used as a benchmark for private reimbursement rates.[ii] This is particularly true for rural health clinics (RHCs), which tend to serve a disproportionately large Medicare population.[iii] This third installment in the five-part series on RHCs will focus on the RHC reimbursement environment.

Medicare Reimbursement of RHCs

Medicare reimburses RHCs on an all-inclusive rate (AIR) for “medically-necessary primary health services and qualified preventative health services furnished by an RHC practitioner.”[iv] The AIR for RHCs is typically calculated by dividing total allowable costs (i.e., costs reasonable and necessary, including practitioner compensation, overhead, and other costs applicable to the delivery of RHC services) by the total number of visits.[v] This AIR calculation (which, of note, only reimburses for professional services, and not for any facility fees) also takes into consideration productivity, payment limits, and other factors.[vi]

Productivity is calculated in terms of visit numbers; a full-time equivalent (FTE) physician’s productivity standard is 4,200 visits, while each FTE non-physician (i.e., nurse practitioner, physician assistant, certified nurse-midwife) has a standard of 2,100 visits.[vii] For an RHC, physician and non-physician practitioner productivity can be combined,[viii] but patient encounters with multiple RHC practitioners or multiple encounters with the same practitioner on the same day only constitute a single visit.[ix] Upon the recalculation at the end of the cost reporting year, if there are fewer visits based on these productivity standards, the AIR rate is lowered.[x]

The 2019 RHC payment limit per visit is $84.70, an increase of 1.5% from the 2018 payment.[xi] An RHC that is an integral part of a hospital (including critical access hospitals) can receive exemptions to the payment limit (i.e., receive a higher payment) if: the hospital has fewer than 50 beds; or, the hospital’s average daily patient census count of those beds does not exceed 40 and meets other additional requirements.[xii]

In addition to the services reimbursed under the AIR, RHCs can also bill Medicare for chronic care management services (determined under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule [MPFS]), which rate was approximately $42 in 2017, as well as for the facilitation of telemedicine services.[xiii] Of note, RHCs may not provide telemedicine services, but they may serve as the originating site (which is reimbursable under the MPFS).[xiv]

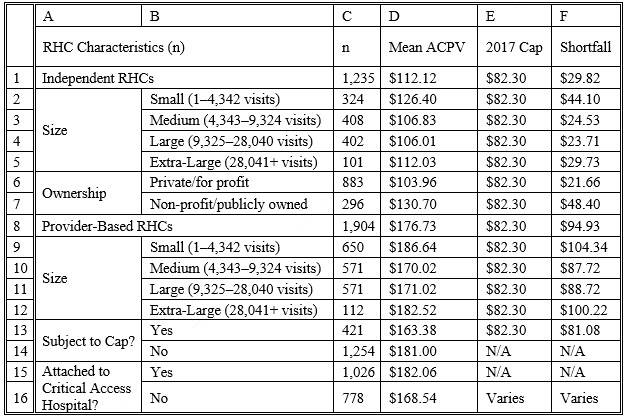

It is important to note that the current RHC payment cap is not enough to cover the average cost per visit to an RHC, i.e., the reimbursement that the RHC receives is less than what it cost them to provide the service, as set forth in Table 1.

Table 1: RHC Mean Adjusted Cost Per Visit (ACPV)[xv]

Medicaid Reimbursement of RHCs

Medicaid reimburses for RHC visits under a prospective payment system (PPS).[xvi] Under the PPS methodology, the state calculates a per-visit rate based on reasonable costs for an RHC’s first two years of operation, increasing the baseline rate each year by the Medicare Economic Index (MEI).[xvii] Alternatively, the RHC may seek an agreement with the state’s Medicaid program under which the RHC receives reimbursement through an alternative payment methodology (APM), which payments would be at least as much as the PPS rate.[xviii] Each state has its own method of applying either the PPS or the APM.[xix]

Like the rest of the U.S. healthcare delivery system, RHCs are moving from volume-based to value-based reimbursement (VBR). Especially considering that 43% of RHCs that are operating at a loss and are at risk for closure,[xx] these entities must be creative in their efforts to stay financially viable during this rapid sea change resulting from payment reform. In one example, five states (Colorado, Hawaii, Michigan, Nevada, Oklahoma) and Washington, DC were selected to participate in the National Academy for State Health Policy’s (NASHP) 2016 Value-Based Payment Reform Academy for federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and RHCs in order to transform how care is delivered at these organizations.[xxi] RHCs are also involved in other VBR initiatives, such as Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) accountable care organizations (ACOs) and APMs under the Quality Payment Program (QPP).[xxii]

Conclusion

The market for rural health services is expected to experience increasing demand in the coming years, due to an aging U.S. population and a greater number of insured individuals due to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA).[xxiii] Both of these factors may increase the number of people seeking healthcare services. As demand increases, the supply of physicians is anticipated to decrease, due to an imbalance between the number of these physicians who are moving toward retirement and the number of residents that are entering these fields.[xxiv] While this may lead to a shortage of primary care services, especially in areas that are already underserved, because RHCs are required to be staffed by midlevel providers at least 50% of the time, RHCs may be relatively immune to the physician manpower shortage.

In most industries, any shortage may lead to rising prices. However, in the healthcare industry, the federal government has some power to set prices through the Medicare program. Further, with respect to Medicare reimbursement, because RHCs are reimbursed on an AIR, even if there is a shortage of primary care services in the next several years, prices (i.e., RHC reimbursement) may not rise to reflect this shortage.

Although RHCs are (purposely) not profitable ventures (as illustrated in the above table), they provide an invaluable service to patients in rural areas who may not otherwise have access to primary services. Due in part to the relative dearth of RHCs in medically underserved areas, free-standing RHCs may consequently be potential acquisition targets by entities such as critical access hospitals or other non-profit healthcare enterprises that are seeking to meet their charitable mission and increase access and quality of care in their communities.

Todd A. Zigrang, MBA, MHA, ASA, CVA, FACHE, is president of Health Capital Consultants, where he focuses on the areas of valuation and financial analysis for hospitals and other healthcare enterprises. Mr. Zigrang has significant physician-integration and financial analysis experience and has participated in the development of a physician-owned, multispecialty management service organization and networks involving a wide range of specialties, physician owned hospitals as well as several limited liability companies for acquiring acute care and specialty hospitals, ASCs, and other ancillary facilities.

Mr. Zigrang can be contacted at (800) 394-8258 or by e-mail to tzigrang@healthcapital.com.

Jessica Bailey-Wheaton is Vice President and General Counsel for Heath Capital Consultants, where she conducts project management and consulting services related to the impact of both federal and state regulations on healthcare exempt organization transactions, and provides research services necessary to support certified opinions of value related to the Fair Market Value and Commercial Reasonableness of transactions related to healthcare enterprises, assets, and services. She is a member of the Missouri and Illinois Bars and holds a J.D., with a concentration in Health Law, from Saint Louis University School of Law.

Ms. Bailey-Wheaton can be contacted at (800) 394-8258 or by e-mail to jbailey@healthcapital.

[i] “National Healthcare Expenditure Fact Sheet” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2019, https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nhe-fact-sheet.html (Accessed 5/14/19).

[ii] “Physician Panel Prescribes the Fees Paid by Medicare” By Anna Wilde Mathews and Tom McGinty, The Wall Street Journal, October 26, 2010, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704657304575540440173772102 (Accessed 1/16/14).

[iii] “Modernizing Rural Health Clinic Provisions: Policy Brief and Recommendations” National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services, December 2017, https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/rural/publications/2017-Rural-Health-Clinic-Provisions.pdf (Accessed 12/28/18), p. 3.

[iv] “Rural Health Clinic” MLN Fact Sheet, ICN 006398, January 2018, available at: https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/RuralHlthClinfctsht.pdf (Accessed 12/14/18), p. 1.

[v] “Chapter 13- Rural Health Clinic (RHC) and Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) Services” in “Medicare Benefit Policy Manual” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid, 2018, https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/bp102c13.pdf (Accessed 12/14/18).

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] “Billing Information for Rural Providers and Suppliers” Medicare Learning Network, January 2018, https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/RuralChart.pdf (Accessed 12/14/18).

[x] Ibid.

[xi] The payment cap is updated annually by the Medicare Economic Index (MEI). “Update to Rural Health Clinic (RHC) All Inclusive Rate (AIR) Payment Limit for Calendar Year (CY) 2019” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid, October 12, 2018, https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/MM10989.pdf (Accessed 3/7/19).

[xii] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid, 2018.

[xiii] National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services, December 2017, p. 5.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Ibid, p. 6–7.

[xvi] “Rural Health Clinics (RHCs)” Rural Health Information Hub, https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/rural-health-clinics (Accessed 12/14/18).

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] “Rural Hospital Closures to Ninety-Eight” By Jessica Seigel, National Rural Health Association, February 20, 2019, https://www.ruralhealthweb.org/blogs/ruralhealthvoices/february-2019/rural-hospital-closures-rise-to-ninety-seven (Accessed 3/7/19).

[xxi] “Steps to Engage Rural Health Clinics in Medicaid Value-Based Purchasing Initiatives” By Rachel Donlon, National Academy for State Health Policy, December 2017, https://nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Rural-Health-Clinic-Fact-Sheet.pdf (Accessed 5/14/19).

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] “Since Obamacare Became Law, 20 Million More Americans Have Gained Health Insurance” By Bloomberg, Fortune, November 15, 2018, http://fortune.com/2018/11/15/obamacare-americans-with-health-insurance-uninsured/ (Accessed 5/23/19).

[xxiv] “The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2016 to 2030” Submitted by IHS Markit Limited, for the Association of American Medical Colleges, March 2018, https://aamc-black.global.ssl.fastly.net/production/media/filer_public/85/d7/85d7b689-f417-4ef0-97fb-ecc129836829/aamc_2018_workforce_projections_update_april_11_2018.pdf (Accessed 12/28/18).