Case Study—Royalties and Lost Profits from Intellectual Property Infringement

Theory into Practice

In our literature and at professional conferences, we often discuss the theoretical aspects of our work. For lost profits this includes discussions on the best method for valuing lost profits (before and after, yard stick, but for) or the optimal discount method (ex ante, ex post, or hybrid). Occasionally, these become academic debates with little impact on our “real life” work. This year, I received an assignment that allowed me to apply some of these theoretical ideas to real life circumstances. This case involved stolen intellectual properties and three separate loss categories: lost royalties, lost profits, and unjust enrichment. This article will discuss my approach in assessing these damages, my testimony, and the outcome of the case.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]Resources:

Foundations of Financial Forensics Workshop

Financial Litigation Specialty Webinars

Business and Intellectual Property Damages

[/su_pullquote]

The Case

From the beginning, this case was more complex than most.[1] The plaintiff in this matter was XIP, LLC (XIP). The owner of XIP, through another one of his organizations, Micrin Technologies (Micrin), had manufactured and sold a line of generator interface panels, power distribution units, power supplies, and radio frequency products for cellular towers. The owner created XIP in 2013 to become the owner of Micrin’s drawings, intellectual property, and proprietary information.

Prior to assigning the drawings, intellectual property, and proprietary information to XIP, the owner allowed one of Micrin’s employees to use the drawings and other assets to complete an order with AT&T. Micrin had incurred financial problems that prohibited it from being able to complete the order. This “one off” agreement called for a royalty of $3.00 per unit to be paid for each unit needed to fulfill the AT&T order. The agreement between the owner of Micrin and the employee took place in 2010.

The employee created a company called CommTech which completed the order. After completing the AT&T order, CommTech began selling products based on Micrin’s drawings, intellectual property, and proprietary information to the entire cellular tower industry. It sold products based on Micrin’s drawings from 2011 through 2013.

In 2013, CommTech was sold to a firm which provided a broader array of products to the cellular industry.[2] The new owner wanted the CommTech line of products to further expand its line of products and increase its market share in the cellular tower industry.

That same year, the owner of XIP created Roam Technologies (Roam). This business was managed by one of his sons and obtained exclusive rights to the XIP drawings, intellectual property, and proprietary information. Roam agreed to pay XIP a royalty of 5 percent of sales for products manufactured with XIP’s drawings and intellectual property.

In 2013, XIP sued the former employee of Micrin Technologies, CommTech, and the firm that purchased the CommTech business. Later, Roam and the owner of XIP became part of the lawsuit as third-party defendants. This was because XIP sued CommTech and the former Micrin employee and in turn, CommTech and the former Micrin employee sued XIP, Roam, and the owner of both companies.

Assignment

To begin this assignment, I met with the attorneys representing XIP. At that meeting, I requested various financial documents, both for XIP, CommTech, and the purchaser of CommTech. The purchaser of CommTech was a multi-billion-dollar firm with multiple lines of products. I specifically requested only data related to the sale of products relating to this lawsuit.

Soon after our meeting, ROAM became a party to the lawsuit. On notification of ROAM’s addition, I requested financial data from its inception to the current time.

After reviewing the financial data and current pleading for the case, I met with the owner of XIP and his son, the operator of Roam. From these meetings, it was determined that I would pursue three areas of loss. First, was the royalties XIP should have received from the sale of the products directly related to XIP’s drawings, intellectual property, and proprietary information. These royalties should have been paid by CommTech and the purchaser of CommTech. Second, was the lost profits incurred by Roam. These losses were based on Roam having exclusive rights to produce these products and therefore, sales made by the other entities based on XIP’s drawings should have been Roam’s sales. Third, was disgorgement of profits from CommTech and the purchaser of CommTech.

This assignment followed the path laid out in forensic financial literature.

“Remedies for such infringements are the same. To determine damages, lost reasonable royalties, plaintiff’s lost profits, and /or the defendant’s profits from unjust enrichment may be calculated.”[3]

“Lost profits are one way to measure a plaintiff’s actual damages. Actual damages include lost profits, a reasonable royalty, and corrective advertising.”[4]

Discovery

Discovery and the exchange of documents became a problem in this case. The purchaser of CommTech was very forthcoming with their data. By the time I was hired for this assignment, they had ceased manufacturing and selling products related to XIP. They provided several pages of spreadsheets showing annual sales by product (those products related to XIP’s drawings and information) and the cost of goods sold for each item.

The gathering of CommTech data was another issue. By 2017, CommTech had been out of business for four years. The former owner claimed almost all records had been lost or destroyed. CommTech’s initial information showed approximately $13 million in sales from 2011 through 2013.

Records from CommTech’s major customers (e.g., AT&T) were subpoenaed. Copies of purchase orders were reviewed. This information showed over $25 million in sales over that same period.

Finally, 10 boxes of invoices and purchase orders were found in a former CommTech employee’s attic. A review of those records along with the QuickBook records showed sales of over $31 million.

Cost and expense data were even more difficult to find. The opposing economic expert noted his reluctance to use CommTech’s QuickBook data for cost of goods sold due to errors he found with the inputs. Concerns with the general, sales, and administrative costs were also noted.

Lost Royalties

The initial analysis was to determine the value of XIP’s lost royalties. Throughout the life of the XIP’s drawings, intellectual property, and proprietary information, only twice were they allowed to be manufactured and sold by another firm. CommTech was allowed limited usage to complete an AT&T order. The royalty CommTech agreed to pay was $3 per unit sold. Roam, the company owned by XIP’s owner and operated by his son, was given rights to manufacture and sell the XIP products. Roam agreed to pay a royalty of 5 percent of the manufactured products’ sales. Basically, the Roam royalty rate was negotiated between the owner of XIP and the owner of Roam, the same person. I opined that neither of these qualified as an arms’ length deal.

“A single license agreement is usually not sufficient to establish a reasonable royalty because a single license does not show general acquiescence.”[5]

Much like determining fair market value by what a willing buyer and willing seller would negotiate, determining a reasonable royalty rate is based on what a willing licensor and willing licensee would negotiate. Average royalty rates for some industries may be found in accounting or financing publications. Because there were no industry standards for royalties on generator interface panels, a broader set of data were used.

A review of legal and financial literature showed throughout most of the second half of the twentieth century, academics and financial experts relied on a “25 percent rule” as the rule of thumb of royalties. This royalty was 25 percent of profits (although whether gross, operating, or net profits was ill defined). An article by Robert Goldscheider in the Duke Law and Technology Review provided an academic foundation for this using “25 percent of profits” as a reasonable royalty rate.[6]

“The Rule holds that licensees of intellectual property normally deserve the lion’s share of the profit because they usually bear the bulk of the business risk associated with bringing the intellectual property to market.”[7]

KPMG studied the use of the 25 percent rule in 2012. “With the growing and critical importance of intellectual property in our modern societies, it is vital for practitioners to be able to value IP adequately. In this paper, [we] explore the 25 percent rule in the licensing market to determine royalty rates and profitability. Goldscheider defines the 25 percent rule as ‘the licensee paying a royalty equivalent to 25 percent of its expected profit for the product that incorporates the IP at issue.’”

The authors found that the reported royalty rates across industries do not converge with the rates generated by the 25 percent rule, although they tend to fall between 25 percent of gross margins and 25 percent of operating margins.”[8]

Based on these two sources, I chose to apply the 25 percent rule to the estimated operating margins. However, the data from CommTech was too fragmented to determine its operating profits. Therefore, I chose to convert the royalty from 25 percent of operating profits to a percentage of sales.

By the middle of 2018, Roam had become a profitable firm. It has been profitable in 2017 and was continuing to show profits in 2018. Using Roam’s sales and cost figures, I estimated the dollar royalty due for 2017 and the year to date 2018 when a 25 percent rate was applied to Roam’s operating profits. I then divided the royalty dollar amount by the sales for that same period. This resulting in a royalty based on sales of 10 percent. This factor was applied to CommTech’s sales and the CommTech purchaser’s sales.

Of course, not all of the products or services sold by either defendant would have provided a royalty to XIP. My office and the staff of the attorney who hired me worked separately to determine the sales of products covered by XIP’s drawings, intellectual property, and proprietary information. After several weeks of work, we arrived at almost the exact same figures. We were able to reconcile the differences to arrive at a single sales figure for each defendant that was used to estimate the lost royalty.

By the time of trial, the CommTech purchaser had settled with XIP. CommTech’s sales of products which would have resulted in royalty payments were estimated to be $17,653,602.20. The lost royalty based on 10 percent of sales was $1,765,360.22. This figure was provided to the trier-of-fact.

Lost Profits

The remaining two analyses, Roam’s lost profits and CommTech’s unjust enrichment, were anchored in lost profit literature.

“In computing lost profits, net profits are the appropriate measure of the loss, but the definition of net profits that is used may not correspond to the net profits that appear at the bottom of an income statement. It may be equal to or lower than the gross margin but often higher than the net margin. However, when such net profits do not eventually equate to cash flow, then the focus of the damage measurement process may shift to cash flows and away from net income.”[9]

Due to the nature of the case, neither analysis was a simple lost sales less avoidable costs equals lost profits calculation. Adjustments were made and the lack of data explained to the trier-of-fact. The detailed explanation of what was and was not included in calculations appeared to help the trier-of-fact in reaching their final decision.

Roam’s Lost Profits

By the time of trial, the purchaser of CommTech had settled with the plaintiffs. Although this defendant was not involved in the litigation come trial, the financial data provided by them was used to estimate Roam’s lost profits.

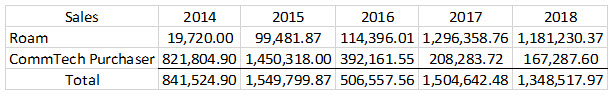

Roam had been given exclusive rights to XIP’s information in 2013, the same year in which the purchaser acquired CommTech from its original owner. Roam did not begin to sell the interface panel until 2014. My calculations assumed all the sales made by CommTech’s purchaser from 2014 through 2018 would have been made by Roam. This was because from 2013 through the end of the loss period in 2018 the interface panels were to be exclusively manufactured and sold by Roam. Any ancillary sales or services relating to the installation of the interface panels were assumed to be tied to the interface panel sales. Without the intellectual property wrongfully acquired in the purchase of CommTech, the CommTech purchaser would have not made any of those sales. Therefore, all of its sales for the interface product, ancillary products and services related to those products were added to Roam’s sales.

From these combined sales, cost of goods sold and expenses were deducted. These expenses were adjusted for the larger sales volume. This was done by assessing the costs of goods sold when Roam had larger sales volume in 2017 and 2018.

This increase in sales occurred while the purchaser of CommTech was shutting down operations related to the interface products. The decline in the purchaser’s sales and increase in Roam’s sales provided anecdotal support to the assumption that Roam would have made the sales the purchaser made in 2014, 2015, and 2016 were it not for the wrongful act.

The figures deducted for general, sales, and administrative expenses were tied to the averages incurred by Roam during its profitable years. I also spoke with the son operating Roam to ensure the business had the capacity to manufacture and install the increased volume.

After Roam’s lost profits were estimated, its actual profits for 2017 and 2018 were subtracted. This appeared to be the cleanest and most straightforward way to address Roam’s profitability during the last two years of the loss period. The resulting lost profit total was $1,040,551.

Unjust Enrichment

This calculation was based on financial literature citing laws which allow “for the recovery of any profits that the defendant made resulting from infringement. This measure of damages is called ‘unjust enrichment’ and focuses on the gain the defendant earned from the infringing activity, rather than the loss the plaintiff suffered.”[10]

The unjust enrichment assessment assumed any sales made by CommTech prior to the company being sold were related to the XIP information. These sales covered the period 2011 through 2013. Secondly, it was assumed none of the ancillary sales would have been made were it not for the sale of the interface panels.

Because of the corrupt data, I relied on two cost of goods percentages reported by CommTech’s economic expert. Without other financial data, my report showed only the gross profits generated by CommTech (sales less cost of goods sold equals gross profits). These figures were provided to the jury with an explanation that not all expenses had been considered. The range of unjust enrichment ran from $9,591,586.86 to $15,956,118.48.

Deposition/Daubert Challenge

I was deposed in this matter. Texas allows for an expert to be deposed for up to six hours on the record. The deposition fell just short of the time limit. Soon after the deposition, the attorneys for CommTech and its original owner filed a motion to exclude or limit my testimony.

The judge in this matter allowed responses only by affidavit. My responding affidavit was twenty-three pages. It covered my report, research providing a foundation for my methodology, a discussion of the data problems (of which the judge was aware), and explanations for each loss calculation. The judge denied the motion to exclude and I was allowed to testify.

Trial

The trial took place over a one-week period in Fort Worth, Tarrant County Texas. On direct, I went through each damage calculation separately, making sure to identify XIP’s loss versus Roam’s loss. We emphasized the lack of financial information and the slow trickle of data had caused me to generate four loss reports.

Cross examination focused mostly on the territory covered in my deposition. Emphasis was placed on my not knowing the industry, not properly applying the findings in the KPMG report, and assuming all the sales generated by CommTech would not have been made were it not for the XIP information. The CommTech economic expert testified the next day providing lesser loss figures to the jury and attempting to discredit my analysis.

The jury returned a verdict in favor of the plaintiffs; XIP, Roam, and their owner. In their award, the jury gave the amounts I estimated for lost royalties and Roam’s lost profits. Some minor reduction was made to the unjust enrichment figures. This was because I had testified not all expenses had been included. The unjust enrichment award was based on the upper end of my reported range.

The defendant’s filed papers with the court to begin the appeals process. Prior to making a formal appeal, the plaintiffs and defendants negotiated a settlement.

Conclusion

This case provided a series of complex issues regarding lost royalties, lost profits, and unjust enrichment. It afforded an opportunity to research financial and legal literature to determine the best theoretical way to assess these losses and make use of this research in a practical way. These calculations were complicated by corrupt or incomplete data.

I found it important to address each loss separately focusing on the data needed for each claim. In addition, communication with the hiring attorneys and their clients was essential in understanding industry standards and issues specific to the case. Preparation prior to deposition and trial also benefitted me in reexamining my thought process and “how I got from here to there.”

In the end, we were able to present a coherent argument to the jury. While the economic expert is only one facet in a trial, the explanation must “dove tail” with the prior testimony and fit within the claims being made regarding a wrongful act.[11] When this takes place, working as an expert in a complex commercial damages case can be beneficial to the client and very fulfilling for the expert.

Allyn Needham, PhD, CEA, is a partner at Shipp Needham Economic Analysis, LLC, a Fort Worth-based litigation support consulting expert services and economic research firm. Prior to joining Shipp Needham Economic Analysis, he was in the banking, finance, and insurance industries for over twenty years. As an expert, he has testified on various matters relating to commercial damages, personal damages, business bankruptcy, and business valuation. Dr. Needham has published articles in the area of financial and forensic economics and provided continuing education presentations at professional economic, vocational rehabilitation, and bar association meetings.

Dr. Needham can be contacted at (817) 348-0213, or by e-mail to aneedham@shippneedham.com.

[1] XIP, LLC v. Michael McGaw, et. al., v. J.K. Henderson, et. al., Cause 348-267268-13, Tarrant County Texas.

[2] The purchaser of CommTech and the intellectual property is not being named because it settled with XIP prior to trial and was not a part of the trial and jury decision.

[3] Litigation Services Handbook, 5th Ed., The Role of the Financial Expert, Weil, Lentz, Hoffman, 2012, 18.35–18.41.

[4] The Comprehensive Guide to Lost Profits and Other Commercial Damages, 3rd Ed., Fannon, Dunitz, 2014, 655.

[5] Ibid., 626.

[6] The Classic 25 Percent Rule and the Art of Intellectual Property Licensing, Goldscheider, Duke Law and Technology Review, No. 006, 2011.

[7] Ibid, 1.

[8] Profitability and royalty rates across industries: Some preliminary evidence, KPMG, 2012, Forward.

[9] Measuring Commercial Damages, Patrick Gaughan, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2000, 200.

[10] The Comprehensive Guide to Lost Profits and Other Commercial Damages, 3rd Ed., Fannon, Dunitz, 2014, 660.

[11] This could be claims being made that a wrongful act occurred or that something else caused the loss claimed by the plaintiff.