Estate of Aaron U. Jones v. Commissioner

The Court Opens to Tax-Affecting

In Estate of Jones, the court addressed the tax affecting issue along with several other issues discussed in the valuation world today, including the proper approach for valuing an operating timber business (income vs. asset-based), the reliability of management projections, and the appropriate discount for lack of marketability. For the first time in 20 years, a valuation expert who tax-affected the earnings of a pass-through entity has had a receptive audience in the Tax Court. This article summarizes this controversy and highlights the valuation issues.

In Estate of Jones,[1] the court addressed the tax affecting issue along with several other issues discussed in the valuation world today, including the proper approach for valuing an operating timber business (income vs. asset-based), the reliability of management projections, and the appropriate discount for lack of marketability.

With this case, for the first time in 20 years, a valuation expert who tax-affected the earnings of a pass-through entity has had a receptive audience in the Tax Court.

Facts of the Case

In May 2009, Aaron Jones gifted interests in an S corporation and limited partnership as part of a succession plan he initiated in 1996 to his three daughters.

The S corporation included Seneca Sawmill Company (SSC) and Seneca Jones Timber Company (SJTC). SSC was based in Eugene, Oregon. It began operations in 1954. In 1986, it elected S corporation status. The company relied heavily on timber from federal lands until the mid-80s when new environmental regulations put access to this timber at risk.

In response to this threat, Mr. Jones started purchasing his own timberlands. In August 1992, he formed SJTC with the sole purpose to invest in, acquire, and manage timberland real property. The inventory produced by SJTC would be SSC’s inventory.

A critical factor in the court’s determination of the appropriate valuation method was the interdependent relationship between the two companies. These included:

- SSC and SJTC shared headquarters.

- SSC owned a 10 percent interest in SJTC as sole general partner (GP), giving SSC the power to manage and control SJTC. As of May 28, 2009, SJTC was SSC’s largest supplier.

- SSC employed 263 people classified as executive, administrative, or manufacturing employees plus 115 to 120 skilled millworkers, 35 to 40 semiskilled workers, and approximately 20 laborers.

- SJTC had 21 employees on the valuation date, consisting of administrative and forestry staff.

- The two companies’ management teams were identical (and paid by SSC), SJTC relied on SSC for human resources, legal services, and its controller in exchange for a $1.2 million annual administrative services fee.

- Both entities were joint parties to their third-party credit agreements, and SJTX’s product (timber) was continuously used as collateral for bank loans. SSC transferred money to SJTC to repay bank loans taken out against its timber, and, as a result, SSC held a $32.7 million receivable from SJTC on the valuation date.

Notably, at the time of the valuation, there was an economic recession; many similar companies did not survive. SSC’s management team revised their projections for both companies in April 2009 to show more conservative results.

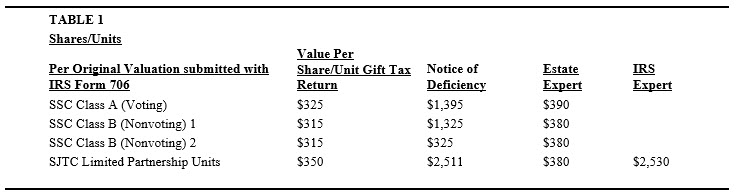

Mr. Jones filed a gift tax return (IRS Form 709) for the 2009 tax year, reporting the total value of approximately $21 million for the daughters’ gifts. In 2013, the IRS issued a notice of deficiency, valuing the gifts at more than $120 million, assessing additional gift taxes of nearly $45 million. Both parties submitted expert reports valuing the transferred SJTC limited partnership units, and the estate’s expert provided a valuation of the transferred SSC stock shares. The IRS did not offer a valuation of SSC’s stock but did submit a rebuttal expert report critiquing the estate’s valuation. Table 1 shows how the various interests were valued on the gift tax return, in the notice of deficiency, and by the parties’ experts.

About the Experts

Robert Reilly was the estate’s valuation expert. With the guideline public company and the discounted cash flow (DCF) methods with a market approach, Reilly valued SJTC and SSC. The IRS’s valuation expert Philip Schwab also valued SJTC as a going concern, using an asset-based approach, specifically the net asset value (NAV) and the guideline public company methods with a market approach. Mr. Reilly concluded that SJTC was worth $21 million on a non-controlling, non-marketable basis and that SSC was worth $20 million on a non-controlling, non-marketable basis. Mr. Schwab concluded that SJTC’s value on a non-controlling, non-marketable base was $140,398,000.

The respondent’s rebuttal expert, John Ashbrook, challenged the valuation of SSC involved Mr. Reilly’s 2009 revised projections and his treatment of SSC’s GP interest in SJTC as well as the intercompany receivable.

Valuation Issues

The court addressed six main valuation issues:

- Whether SJTC should be valued using an income- or asset-based approach

- The reliability of the revised projections used for 2009

- The appropriateness of tax-affecting

- Treatment of intercompany loans

- Treatment of SSC’s 10 percent GP interest in SJTC

- An appropriate discount for lack of marketability

Valuation Approach

The primary dispute between the parties was using an income- or asset-based approach to value SJTC. Consideration was given to the potential impact on the outcome: Mr. Reilly, the estate’s expert, accepted the IRS’s conclusion that SJTC’s timberland assets had a fair market value of $424 million. Using income and market approaches, Mr. Reilly calculated a weighted enterprise value for SJTC of $107 million.

Neither party disputed that SJTC is a going concern. The estate argued that SJTC is an operating company and should be valued based primarily on its earnings from selling logs. The IRS asserted that SJTC is a holding company whose value from its assets and whether or not SJTC is profitable, its primary asset—timberlands—will increase in value. The estate countered that SJTC does not merely buy timberland and hold it, but also has operations including selecting the seeds, planting them properly, safeguarding them, and using sophisticated software to help project long-term sustainability.

The court found that SJTC had characteristics of both an operating and a holding company. Ultimately, the relative weight given to an asset-based approach came down to the likelihood that SJTC would sell its timberlands. The court agreed with the estate that a sale was unlikely, because (1) the block of stockholders of SJTC limited partnership units could not force a sale under the existing partnership agreement, and (2) SSC, as GP had the exclusive authority to direct a sale, would never do so. This conclusion was further supported by the estate’s argument, embraced by the court, that even though SJTC and SSC are separate legal entities, their interdependent relationship should be considered when valuing them. The court explained:

SSC’s continued operation as a sawmill company depended on SJTC’s continued ownership of timberlands, and there was no likelihood that SSC would direct SJTC to sell its timberlands. At the same time, SSC continued operations as a sawmill. Additionally, they had almost identical ownership and shared administrative staff. Therefore, based on the facts above, we conclude that SJTC and SSC were so closely aligned and interdependent that, in valuing SJTC, it is appropriate to take into account its relationship with SSC and vice versa.

The court concluded that “an income-based approach, like Mr. Reilly’s DCF method, is more appropriate for SJTC than Mr. Schwab’s NAV method valuation.”

2009 Projections

The IRS argued that the April 2009 revised projections that Mr. Reilly used were unreliable. SJTC’s management made the projections less than two months after the company’s annual report was issued, out of concern that the company might violate its loan covenants. The court noted that the revised projections, using the same methodology as those included in the annual report, were relied upon for business decisions as of the valuation date. Mr. Schwab, the IRS’s valuation expert, used them in his market-based valuation. He averaged the revised projections with those from the annual report because he thought they “may have represented the worst-case scenario and were overly pessimistic….”

The court went on to conclude that “the only ground for challenging the reliability of the revised projections is that the volatile economic conditions meant that they were not reliable for long. This is precisely why management wanted the revised projections. As they were the most current as of the valuation date, Mr. Reilly’s use was appropriate.”

Tax Affecting

Mr. Reilly tax-affected SJTC’s earnings using a 38 percent rate for combined federal and state taxes to calculate SJTC’s net cash flow and the cost of debt capital to determine the appropriate discount rate. He also considered the benefits of a pass-through entity’s avoidance of a tax on dividends. Mr. Reilly applied a 22 percent premium to SJTC’s weighted business enterprise value to reflect this benefit.

The IRS challenged tax-affecting, arguing that SJTC was a partnership and not subject to entity level tax. There was no evidence that SJTC would convert to a C corporation in the near future. The estate responded that a zero-tax rate at the entity level would overstate the value of an interest in SJTC and that a hypothetical willing buyer and seller would take into account both the partners’ tax liabilities and the benefit of avoided dividend taxes.

The court found that Mr. Reilly had more accurately considered the tax consequences of SJTC’s pass-through status for a willing buyer and seller. It also distinguished its previous decisions rejecting tax-affecting as limited to the particular facts of those cases. While not exact, Mr. Reilly’s tax-affecting analysis was “more complete and more convincing than the respondent’s zero tax rate.”

Although the court’s discussion of tax-affecting focused on SJTC, Mr. Reilly’s tax-affected SSC’s earnings used the same method, with the exception that a different rate was used to capture the dividend tax avoided adequately. The court accepted the tax-affecting of SSC for the same reasons.

Intercompany Loans

Mr. Reilly excluded SSC’s receivable and SJTC’s offsetting liability, taking into account the intercompany interest income and expense. The IRS argued that Mr. Reilly eliminated the debt to avoid leaving SJTC with a negative value. In fact, the IRS claimed, it should have been treated as a nonoperating investment asset and added to SSC’s value. The court rejected this argument. The size of the intercompany debt was directly related to the connection between the companies and, therefore, the debt was an intercompany clearing account, not an investment in a separate company.

SSC’s GP Interest

The IRS contended that SSC’s control over SJTC by virtue of its 10 percent GP interest should be reflected in its value and that Mr. Reilly understated it by limiting it to expected distributions. The court concluded that the GP interest was an operating asset, and the controlling interest ensured the two companies operated as a single business. For that reason, Mr. Reilly’s treatment of GP’s interest in SJTC was appropriate.

Discount for Lack of Marketability

The two experts were only 5 percent apart on the discount for lack of marketability: Mr. Reilly used a 35 percent rate, and Mr. Schwab used 30 percent. The court disagreed with the IRS’ claim that 35 percent was excessive and that Mr. Reilly failed to adequately explain how he arrived at that figure, noting the appendix in Mr. Reilly’s report that described his reasoning in detail with empirical models and restricted stock studies. The court accepted Mr. Reilly’s 35 percent discount, finding it to be better supported and explained than Mr. Schwab’s 30 percent rate.

Observations

Most valuation experts tax-affect earnings of pass-through entities. The Tax Court may now be more receptive to the idea, while the consensus is that there is no clear-cut guidance on a specific rate or approach to use. Like most valuation concepts, the application of tax-affecting depends highly on the particular facts and circumstances of each valuation engagement. Estate of Jones demonstrates the importance of competent, expert testimony to explain in detail (1) the reasons for tax-affecting, (2) the methods and calculations used to adjust earnings, and (3) the benefits as well as the costs associated with pass-through status.

The full article was published in The Value Examiner January/February 2020 issue.

Kimberly Tavares, CVA, is the founder of PacWest Accounting, Inc., a full-service accounting/litigation support firm that provides outsourced CFO advisory services as well as business valuation and forensic accounting services. She has served as an expert witness in San Diego and Orange counties in California. She has more than 18 years of experience preparing valuations in numerous industries, including technology, construction, health care, professional services, trucking, and manufacturing. Ms. Tavares graduated from California State University Fullerton with a BA in accounting. She is CFO of the Newport Beach Chamber of Commerce Board of Directors, a 2016 NACVA/CTI 40 Under Forty honoree, a nominee for the Connected Women of Influence 2018 President’s Award, and the 2016 and 2018 Orange County Business Journal Women in Business Award.

Ms. Tavares can be contacted at (949) 873-3126 or by e-mail to Kim@pacwestaccounting.com.

[1] T.C. Memo. 2019-101.