Case Study

Changing Assignments from Fairness Opinion to Business Valuation

Commercial damages matters can be challenging and require a flexible mind when “wrapping your brain” around the issues and facts of a particular case. Beginning in the first quarter of 2019 and running through October 2020, I had an assignment which began with a simple fairness opinion letter and ended with my testifying at trial to defend my valuation of the business. This article will review the changes in my assignment, the decision to value the business, the Daubert challenge brought by the opposing side, and testifying via Zoom at the trial. In the end, this case is an example of how remaining flexible can allow an expert to fulfill the assignments needed to meet an attorney’s case strategy and maintain the expert’s integrity in the analysis and conclusion.

Beginning in the first quarter of 2019 and running through October 2020, I had an assignment which began with a request for a simple fairness opinion letter and ended with my testifying at trial to defend my valuation of the business. This article will review the changes in my assignment, the decision to value the business, the Daubert challenge brought by the opposing side, and testifying via Zoom at the trial.[1]

General Facts of the Case

Late in the first quarter of 2019, I was contacted by a law firm for whom I had provided several commercial damages analyses. These cases had included lost profits, business interruption, and business destruction (therefore business appraisals). In the current case, a bank had brought a lawsuit against a business owner for default and non-payment on approximately $5,000,000 in debt. As a part of the litigation, the business owner had countersued claiming misrepresentation and fraud by the bank. The attorneys retaining me were representing the former business owner.

The facts appeared straight forward. The business was a manufacturer and distributor of LED lights. The company did not own the manufacturing facilities only the intellectual property related to the lights’ design. Their supply chain stretched to China. The demand for LED lights remained high during the time of the alleged wrongful acts and tariffs imposed on Chinese goods during that period did not appear to reduce the import of LED lights manufactured in China.

The business began operations in 2012 with annual sales of $834,933 and operating income of $32,886. In 2015, the owner brought in new management to stimulate company growth. By its last full year of operation in 2017, the business had $17,904,707 in sales and an operating income of $3,705,296. To achieve this rapid growth, the business increased its borrowing to allow for additional working capital and increased inventory.

At the beginning of 2018, an investment capital firm signed a letter of intent (LOI) offering $35,000,000 for the business, debt free, cash free. Due diligence took place during the first quarter of 2018. The purchasing firm anticipated completing its due diligence and negotiating its final purchase price at the start of the second quarter 2018. The completion of the due diligence was delayed and the prospective purchaser requested an extension of due diligence for the second quarter.

During this time, the bank and the business’ relationship deteriorated. The bank moved the company’s debt to its destressed loan department. It had also “turned off” the company’s bank sponsored credit cards. Due to the delays in completing the purchase agreement, on 6/1/2018, the bank forced the business into receivership. While in the business was in receivership, the investment capital firm made a cash offer of $12,000,000 for the assets of the business. The bank refused the offer, and the business was liquidated.[2]

Because the liquidation of the business did not satisfy the outstanding debt, the bank sued the owner (who had personally guaranteed the loan) and the owner in turn sued the bank for its part in the failure of the sale of his business.

Initial Assignment

My initial assignment was to offer a fairness opinion letter stating the initial LOI of $35,000,000 was fair. To provide a fairness opinion letter, the expert reviews the LOI being made for a particular enterprise and that business’ financial records. It does not require a full business appraisal; however, the analysis (in my opinion) requires much of the same analyses applied when valuing a business. The expert should keep in mind this is an offered purchase price and the prospective buyer may change the offered price or even walk away from the proposed transaction based on what is found during the due diligence process. Therefore, the fairness opinion reflects an opinion regarding the current price offered based on current information. In the end, a letter provided by the expert states the offer is fair from a financial point of view (provided the financial record review supports such an offer).

The data available for this analysis was the most I ever received in a commercial damages case. There were detailed financial records; income statements, balance sheets, sources, and uses tables. In addition, the business had hired a merger and acquisition firm to review its operation and provide suggestions for operational improvement and projections for the next two to three years. The consulting firm’s report was shared with the investment capital firm seeking to buy the business. The prospective buyer also hired a consulting firm to perform its own analysis of the business. The second firm also provided a detailed analysis and five-year projections for the firm. Both sets of information were made available to me.

In the end, I felt the offer was in excess of the fair market value of the firm. However, e-mails showed this was a strategic purchase for the investment capital firm. Therefore, I felt they were offering more for this business because it fit in their strategic plan. They did not look at this business as a stand-alone firm but valued it from where the business fit in their portfolio. On 5/8/2019, I provided a fairness opinion letter stating the offer was fair from a financial point of view.

Second Assignment

After forwarding my fairness opinion letter, I did not receive any communication from the hiring attorneys for about three months. When I was finally contacted, the attorneys felt a more detailed analysis was needed. They requested an updated fairness opinion letter and a business appraisal to support my fairness opinion. This led to a discussion regarding my opinion that the purchaser had offered more than the company was worth and I believed my fair market value would reflect a lesser amount. They understood and asked me to move forward with my opinion.

In the interim, the business owner and the director of the investment capital firm had been deposed. This provided a historical perspective of the events leading to the failed sale.

For this second assignment, I first completed a business appraisal of the now defunct company. The date of estimate was 12/31/2017. The LOI was made on 2/1/2018. For the LOI, the prospective buyer relied on historical data for the period ending 11/30/20017. However, due diligence ran through the first quarter into the second. By that time, the year-end data had been made available to the prospective purchaser.

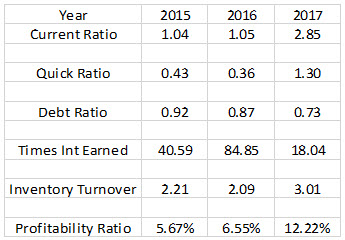

Various ratios confirmed the success and increased debt strain brought about by the rapid growth of the company.

The current and quick ratios showed an improvement in the ability of the business to pay its current liabilities. The growth in the current assets improved the debt ratio even with the growth in the firm’s debt. But the times interest earned figure showed the increase in the cost to service the debt. The inventory turnover and profitability confirmed the sales growth had been beneficial for the business. It was not growth for growth’s purpose but growth to enhance profits.

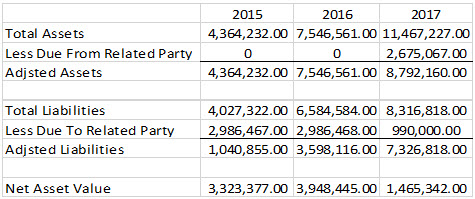

All three traditional approaches were considered for valuing the business: asset approach, income approach, and market approach.[3] After adjusting the balance sheet for “due to” and “due from” related parties’ items, the net asset value based on book value appeared this way.

The market approach was problematic. Research showed the following firms to be leaders in the LED lighting field:

- Phillips Electronics, NV

- Cree Corporation

- Osram Opto

- Digital Lumens, Inc.

- General Electric

- Toshiba Corp

- Digital Plc

- Cooper Industries, Plc.[4]

Unfortunately, most of these corporations provide several products and services in multiple markets. Their corporate filings did not segregate their LED lighting sales and profits.

Further research provided four firms listed as being LED lighting development, manufacturing, and sales companies.

- Leddar Tech

- Rambus

- Enlighted

- LIFX[5]

Only two of the researched companies (Cree Corporation and Rambus) were listed on stock exchanges in the United States. On further review, Rambus reported being heavily weighted in the semi-conductor business. Again, the sales and profits for the two different segments were combined and not separated. This left only one data point for the market approach—the financial information for Cree Corporation.

As I learned in my introductory econometrics class, one data point does not make a trend. My report explained this lack of market data and why I chose to not determine a fair market value of the business based on the market approach.

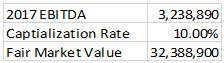

For the income approach, the LED lighting business’ 2017 EBITDA was determined.[6] That figure was $3,238,590. The business was projected to continue its rapid growth over the next five years. The company had settled a lawsuit in 2017. The settlement payment was $470,000. For future years, it was assumed the need for capital expenditures to keep up with the grow was $470,000. This meant $470,000 added back in for the removal of the one-time settlement cost and $470,000 taken out to reflect necessary capital expenditures.

The capitalization rate to be applied to the EBITDA became controversial. The consulting firm hired by the seller projected a 45% increase in sales and 58% increase in operating income in 2018. The consulting firm hired by the purchaser was almost as aggressive in their projections.

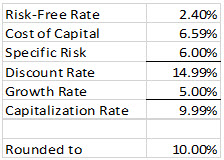

To arrive at a capitalization rate, I used the build-up method for determining the discount rate and from that figure subtracted a 5.0% growth rate. The discount rate included a risk-free rate that was based on the current yield on ten-year constant maturity U.S. Treasury Bonds. To that was added a cost of capital rate based on data from Aswath Damodaron’s Cost of Capital data.[7] A specific risk factor of 6.0% was added to complete the build-up.

I described the specific risk this way: “[A]n additional 6.0% has been added for risk specific to [the company]. At the end of 2017, [the business] was a firm that in six years had gone from $834,933 in sales and $32,886 in operating profit to $17,904,707 in sales and $3,705,296 in operating profit. [The consulting firm’s] memorandum projected more than $25 million in sales and $5 million in operating profit in 2018. This firm has increased its debt to help it grow. Debt service payments (interest and principal) erode cash flow. While [the company’s] financials showed the company’s ability to currently service its debt, the impact on its cash flow should be included in the risk premium. Because [the business] did not manufacture the product itself, risk related to its supply chain must be considered. Conversely, by not manufacturing [this enterprise] was more flexible to design, inventory, and sell updated products without retooling or holding on the large amounts of stale inventory. This too was taken into consideration when setting the specific risk premium.”

This explanation was important because it showed the specific company risks considered when arriving at the specific risk factor. This was important in refuting the opposing sides argument that no company related risk factors were included in my capitalization rate. These risk factors were discussed at length during my cross-examination.

The resulting capitalization rate was 10%.

The multiple to EBIDTA applied by the prospective purchaser was five. However, their five times EBITDA multiple was based on the EBITDA projected by its consulting firm. The resulting EBITDA was nearly twice my EBITDA figure.

The resulting value from the 10 times EBITDA applied to my estimated EBITDA was $32,388,900.

This was the fair market value I reported for this business.

As a part of this second assignment, I updated my fairness opinion report. To my initial opinion, I added the definitions for fair market value, investment value, enterprise value, and liquidation value. This gave a foundation for my testimony as to why there was a $3,000,000 difference between my fair market value and the LOI business value. The fact the fairness opinion letter was written about an offer from a specific buyer as opposed to a hypothetical buyer provided the foundation for why the prospective purchaser would offer more than my fair market value.

Daubert Challenge

As to be expected in a commercial damages case, the opposing side filed a Daubert challenge to exclude me.[8] The expert hired by the bank’s attorney argued my report was greatly flawed and did not provide relevant or reliable information for the trier-of-fact.[9] Most of the arguments put forth in the motion to exclude were common differences between experts that provide for cross-examination fodder.[10]

Because of the COVID-19 restrictions, the judge held a Zoom hearing to hear the arguments. I was not asked to attend; however, I provided a 12-page declaration reviewing my report and refuting the expert’s criticism.

Civil Courts in Texas have not been allowed to hold jury trials since April 2020.[11] Because this was a bench trial, the judge ruled that she would hear testimony from all experts and give their testimony the weight she felt it deserved.

Trial

To use a young person’s term, the trial was a “major beating.” Being a Zoom trial, testimony was limited to only four to five hours per day. The trial lasted over two months. I testified toward the end of the trial providing my direct testimony on a Friday. I returned on a Tuesday (Monday was a holiday) and was cross-examined that morning.

Little questioning was directed at my fairness opinion letter. However, I was asked about its content. Most of the time was spent on my business appraisal. The opposing side quizzed me as to my knowledge of business valuation standards and literature and why I relied on Revenue Ruling 59-60. Their hardest attack was against my capitalization rate and why I used a 10 times EBITDA multiple as opposed to the five times EDITBA applied by the prospective purchaser and its consulting firm.

This gave me an opportunity to discuss the large growth factors used by the prospective buyer for projecting the EBITDA and how their projected greater EBITDA made for a greater business value. It also gave me an opportunity to discuss a linear 5.0% growth rate as opposed to the prospective buyer’s double digit growth rates for short term followed by lesser growth rates, which based at current growth rates would be less than 5.0%.

The cross-examination provided a “teaching moment” allowing me to explain why my analysis made sense. This focused not only on the capitalization rate but also why one specific buyer might pay more than a hypothetical willing buyer. The judge appeared to accept my reasoning. There was no redirect, and the judge had no questions.

It is my understanding the opposing side did not call their expert as a rebuttal witness. The next week, the judge asked each legal team to provided briefs regarding certain legal issues relating to the case. As of the writing of this article, she has provided a verdict in this matter.

Conclusion

This case began as a simple assignment to provide a fairness opinion letter, but that assignment changed over time. This was not the first time I had been asked to provide a fairness opinion letter in a litigious situation. In prior cases, that was the extent of my work. As this litigation progressed, the need for additional work grew. I was asked to provide a business appraisal along with an updated fairness opinion letter. This request met the attorney’s case strategy.

Allyn Needham, PhD, CEA, is a partner at Shipp Needham Economic Analysis, LLC, a Fort Worth-based litigation support consulting expert services and economic research firm. Prior to joining Shipp Needham Economic Analysis, he was in the banking, finance, and insurance industries for over twenty years. As an expert, he has testified on various matters relating to commercial damages, personal damages, business bankruptcy, and business valuation. Dr. Needham has published articles in the area of financial and forensic economics and provided continuing education presentations at professional economic, vocational rehabilitation, and bar association meetings.

Dr. Needham can be contacted at (817) 348-0213, or by e-mail to aneedham@shippneedham.com.

[1] Revenue Ruling 59-60, Internal Revenue Service, www.irs.gov

[1] UMB Bank, N.A. v Kobi Electric, LLC, et. al., 017-299994-18, Tarrant County, Texas

[2] If you are perplexed by this series of events, so was I. Unfortunately, no documents or trial testimony provided insight as to the bank’s motives for forcing the firm into receivership nor rejecting the $12,000,000 cash offer.

[3] Revenue Ruling 59-60, Internal Revenue Service, www.irs.gov

[4] LED Lighting Market Size, Trends, Growth, Industry Report 2018–2025, Grand View Research

[5]Yahoo finance, Company Profile, https://finance.yahoo.com

[6] Earnings before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization (EBITDA)

[7] Cost of Capital, Aswath Damodaron, New York University, www.nyu.edu

[8] In Texas courts, a Daubert challenge is referred to as a Robinson challenge, named after the case in which the State Supreme Court first agreed to move from the Frye standard to the Daubert standard.

[9] The expert is an active NACVA member.

[10] As an example, using EBIT instead of EBITDA and not including large enough risk premium in the capitalization rate.

[11] This ban has been extended through the end of January 2021.