Valuation Guidelines for Mineral and Renewable Interests

A Data Analytics Approach

The valuation of minerals and renewables falls outside the usual guidelines of real property appraisal, where real property broadly defined includes land, everything permanently attached to it, at, above, and below the earth’s surface and all the interests, benefits, and rights inherent in the ownership collectively referred to as “the bundle of sticks”. This is because most appraisers commonly value land, houses, ranches, surface structures, and businesses. Sub surface real property appraisals is more specialized where appraisers usually value royalty income based on production from reservoirs beneath the surface. This article provides an overview of the multiple other factors that are considered when valuing renewable and energy projects.

Common Guidelines

The valuation of minerals and renewables falls outside the usual guidelines of real property appraisal, where real property broadly defined includes land, everything permanently attached to it, at, above, and below the earth’s surface and all the interests, benefits, and rights inherent in the ownership collectively referred to as “the bundle of sticks”. This is because most appraisers commonly value land, houses, ranches, surface structures, and businesses. Sub surface real property appraisals is more specialized where appraisers usually value royalty income based on production from reservoirs beneath the surface. Commonly described as reservoir economic analysis, this valuation practice uses readily available economics software programs. Monthly rates of production, commodity prices, escalation factors, reservoir decline rates, O&M are input variables along with a calculated discount rate used to generate a NPV valuation. Similarly, many of the same production variables that characterize royalty income for mineral valuations can be utilized to model the revenue streams generated by wind turbines. Aside from these usual practice areas, the appraisal profession has seen the growing impact of surface operations that result in environmental hazards, spills, surface destruction, and groundwater contamination.

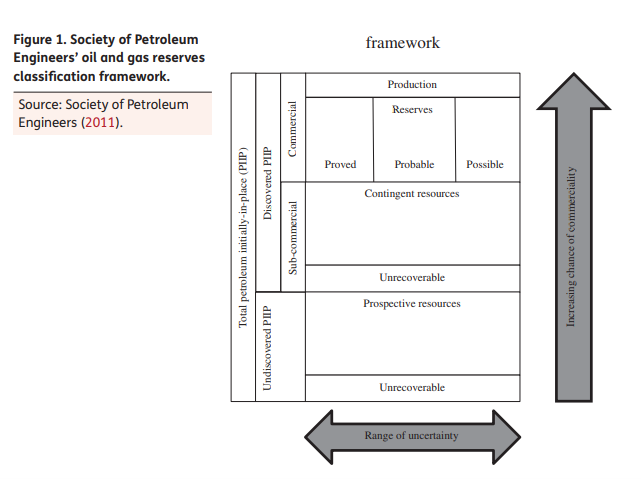

The application of data analytics used in oil and gas reservoir economic analysis provides a useful analogue for renewable economics. These comparisons to mineral analytics can play an important role in developing algorithms used not only for mineral estate valuations but surface estates as well. They both have revenue profiles based on variable production, pricing, and royalty schemes, with applicable discount rates including risk factors. The development of the guidelines for valuing minerals by the Society of Petroleum Valuation Engineers serves comparatively as a blueprint for Wind Valuations. The comparison originates in part from the combination of the two in assessing the value of the land estate and their build up pricing algorithms. For example, the framework for classifying mineral reserves is broken primarily into proved and unproved properties. These categories can be further subdivided into probable and possible. (See Figure 1)

As an analogue, you have proved developed and unproved renewable assets (wind and solar) that exist with surface estates. Unproved are less certain to be developed assets that can be further sub-classified into probable and possible. (Based on wind maps, nearby wind developments, transmission access, production, and investment tax credits, proposed renewable legislation, etc.) As an example, the National Renewable Energy Lab (NREL) has a data base with turbine farm locations. That information plus maps of major transmission lines are good sources to determine accessibility to individual State’s grids and the likelihood (probability) for development of renewable generators on the property.

The steps in appraising a lessor’s interest requires following the standard valuation practice guidelines for the three indicators of value: cost, sales comparison, and income approaches. Depending on the depth and integrity of available data, one of the approaches is chosen to best represent the value of the wind ownership rights. If the property is currently under production, the lessor should have copies of past revenue records in their possession representing their interest based on the royalty terms in the wind lease and the energy production from the turbines on the property. Those terms usually specify royalty payout percentages through the life of the lease and, in most cases, escalators stepping up the royalty every five to seven years to terminus.

Therefore, the dominant approach becomes a NPV analysis of the income streams from the production of the turbines based on contracted prices from a power purchase agreement (PPA) or market rates based on a merchant model. Most wind farms have a PPA for most if not all the energy production from the wind farm usually extending through the first 15 years of the project life. Subsequently, the PPA may be renewed, a new one is acquired, or the production is sold at prevailing market prices. Just as with mineral valuations, a discount rate is determined through a build-up method that incorporates the weighted average cost of capital (WACC), the impact of transmission constraints, commodity pricing, renewable energy certificates and other risk factors such as remaining life of the turbines, repowering considerations, and decommissioning.

Environmental Impacts

Aside from these usual practice areas, the appraisal profession has seen the growing impact of surface operations that result in environmental hazards, spills, surface destruction, and groundwater contamination. The appraisal of properties impacted by environmental contamination requires extensive analysis to determine what impact remediation of the property would affect the feasibility of site development or redevelopment during remediation and use after remediation. In these appraisals, both NACVA and USPAP are consistent with promulgated standards and competency rules where the appraiser must be aware of, understand, and correctly employ recognized methods and techniques to produce a creditable appraisal. Accordingly, the appraiser must have the requisite knowledge of such appropriate methods but need not be an expert on the scientific aspects but utilize technical data and analysis prepared by other specialized evaluators and environmental engineers.[1]

Now, with the expansion of renewable incentives and corporate sustainability initiatives, contamination of property may be impacted from externalities that not only include wind turbines but solar power generators, power grid substations, overhead transmission lines as well as oil and gas infrastructure. Guidance for the proper valuation of properties impacted by environmental contamination including externalities is specified by USPAP, Advisory Opinion 9 where the difference between the unimpaired and impaired values of the property being appraised is provided by the following formula:

Impaired Value = Unimpaired Value – Cost Effects – Use Effects – Risk Effects

This difference can be due to the increased risk and/or costs attributable to the property’s condition, where environmental risk is defined as: the additional or incremental risk of investing in, financing, buying and/or owning property attributable to its environmental condition.

Diminution of Value

In the past few years, as the development of wind farms has become more widespread, more rural land appraisals have been on property with turbines sited on, adjacent to, or within eyesight of the subject property. For those landowners fortunate enough to have wind farms developed on their property, any perceived nuisances are outweighed by royalty income just as pumpjacks and oil and gas pipelines represent welcomed cash crops. But for other outlying landowners, there can be perceived uncertainties affecting their land’s environmental attributes resulting in a diminution of value (property value diminution).[2]

For some of those landowners, many resent the environmental impacts: noise pollution that is created by the spinning turbine blades that create a humming vibration or sound; shadows and a flicker effect from the blades spinning through the sun’s rays; health impacts created by the turbine warning lights; and finally, the impairment of the visual attributes of the land’s topographical vistas. Depending on the siting of the turbines (usually placed on higher ground to take advantage of the wind power dynamics), turbine placement can become more visibly distracting to otherwise protected views. In addition, overhead power lines linking the turbines to substations (power transformers) are additional distractions. These environmental externalities could eventually have economic consequences for any future estate planning contemplating the sale or transfer of interests not only of the subject property but adjacent properties as well.

When the appraiser addresses the diminution of value of a contaminated property (in this case externally from turbines) the appraisal must take into consideration cost, use, and risk effects to satisfy USPAP Standards Rule 1-4.[3] Use effects are those impacting the economics of the property usually near proposed developments. While most wind farms are sited in rural settings, more are approaching more densely populated housing areas especially in the Northern part of the country. In those areas, class action lawsuits have necessitated developers to provide price guarantees to protect proximate owners from diminution of values. And in scenic areas of the Texas Hill Country, there has been significant resistance to wind development where the use effects are perceived to be significantly impacted by turbine siting.

In accordance with Standards Rules 1-2(e) and 1-3(b),[4] the appraiser must consider all relevant factors in developing an opinion of the highest and best use of the property in its impaired condition. For example, in addition to scenic obstruction from turbine siting, there have been case studies of Texas rural ranch areas specifically known for prized white tail deer habitats that are now perceived by trophy hunters to be impacted or stigmatized by condensed turbine placement. The resulting impact on valuations can be a significant diminution in value or discount. More so than the impairment of common ranch land where in some cases the diminution of value is limited to none.

Summary

Real property is commonly defined by a set of ownership rights referred to as a collection or bundle of sticks with each stick identified as a right. The valuation of these rights is guided by specific standards and principles of appraisal practice. Due to the parallels in production variability, the impact of commodity prices, inflation, project duration, royalty algorithms, and more, comparisons can be modeled to utilize available data analytics to understand attributes and develop valid economic valuations.

[1] Appraisal Standards Board, Advisory Opinion 9, “The Appraisal of Real Property That May Be Impacted by Environmental Contamination, “USPAP” Advisory Opinions, 2012-2013 ed. (Washington, DC: The Appraisal Foundation, 2012), Standards Rule 1-1(a), Lines 55–61.

[2] Ibid., Lines 74–76

[3] Ibid., Lines 168–174

[4] Ibid., Lines 149–151

Frank Horak has over 30 years’ experience in energy, economics, and valuation. His experience began as an engineering intern at Texas Instruments Inc. and Boeing Aerospace. He had a broad range of financial consulting engagements with Arthur Andersen & Co., Price Waterhouse, and several other management consulting firms.

Subsequently he played a lead role in the concept development, management, and oversight of venture-based technology projects including energy economics, portfolio valuation modeling, and renewable energy development.

Mr. Horak was an Acting Director of Real Estate and a lecturer in finance and accounting at the Graduate School of Business at the University of Texas at Austin. He also has been a guest lecturer at the Schools of Law at The University of Texas and University of Houston. He is a frequent speaker on the valuation of minerals and alternative energy assets and interests.

Mr. Horak can be contacted at (512) 470-1771 or by e-mail to Frank@AstekEnergy.com.