Imagining a World with A (Mostly) GAAP-Based Income Tax

Part I of II

This is the first of a two-part article related to the proposed (mostly) GAAP-based income tax in the (perhaps fatally wounded) Build Back Better Act. While the Build Back Better Act may be dead, the GAAP-based income tax is a polarizing concept that may be resurrected soon. The first part focuses on why there is a push by someâand pushback by othersâon such a tax. The second part imagines some changes that may occur in a world where big companies pay taxes based (mostly) on GAAP income.

This is the first of a two-part article related to the proposed (mostly) GAAP-based income tax in the (perhaps fatally wounded) Build Back Better Act. While the Build Back Better Act may be dead, the GAAP-based income tax is a polarizing concept that may be resurrected soon. The first part focuses on why there is a push by someâand pushback by othersâon such a tax. The second part imagines some changes that may occur in world where big companies pay taxes based (mostly) on GAAP income.

Introduction

While the only guarantees in life may be death and taxes, there will always be debates over how much big companies should pay in income taxes. The proposed Corporate Profits Minimum Tax (CPMT) replaces most of the tax code with GAAP financial reporting in certain situations. Proponents of the proposed CPMT contend some big companies shirk their civic responsibilities by legally taking advantage of the tax code to report substantially lower pre-tax income to the IRS than they report in their GAAP-based financial statements. Opponents counter that it is better to change the tax codeâif the goal is to make these companies pay more in income taxesâthan to effectively replace it with GAAP financial reporting.

Why Is There a Difference Between Tax Accounting and GAAP?

A company keeps two sets of books because they are used for different purposes. One set is used to raise revenue and provide incentives or disincentives via income taxes. The other set is used for communicating a companyâs performance to other stakeholders. Having two sets of books can cause a company to report income that is significantly higher for one set than the other at a point in time.

There are three reasons why income can be different between the two sets of books:

- Permanent differences, which never reverse over time. Some permanent differences provide tax incentives, such as tax-free municipal bonds, which are not taxed (due to the tax incentive) but are included in GAAP income (because the income is real). Other permanent differences provide tax disincentives, such as penalties and fines, which are not deductible for tax purposes (otherwise the government would effectively pay part of these penalties and fines) but are an expense for GAAP purposes (because the company in fact paid these expenses).

- Temporary differences, which always reverse over time. These differences are also due to incentives and disincentives built into the tax code. For example, depreciation is often recognized at a faster rate for tax purposes than GAAP purposes (GAAP depreciation is theoretically based on expected economic obsolescence) to encourage investment and mitigate bias against capital expenditures.[1]

- Other differences, which can be due to a variety of reasons. Prominent examples include employee stock options and goodwill. Employee stock options use different valuation methodologies (forward looking for GAAP; backward looking for tax) and valuation dates (when issued for GAAP; when exercised for tax). Goodwill is not amortized and is subject to impairment tests for GAAP whereas goodwill may or not be amortized and is not subject to impairment tests for tax.

Origins of the GAAP-Based Income Tax

The concept of using GAAP financial reporting for income tax purposes is not new. In fact, it was tried in the late 1980s in connection with the sweeping tax overhaul of 1986, under the creatively named Business Untaxed Reported Profit (BURP) adjustment. If companies reported higher pretax income under GAAP reporting than the tax code, they had to spit up 50% of the difference due to the BURP adjustment.[2] The BURP adjustment was short lived as it was only effective for three years: 1987â1989.[3]

The debate over the BURP adjustment in the 1980s was like the current debate over the proposed CPMT. Proponents think certain companies are using tax loopholes to not pay their âfair share.â (Perhaps proponents should call it âFinally a Realistic Taxââor âFARTââas a more interestingly named replacement for BURP.) Critics counter that using GAAP reporting for tax purposes may result in many negative consequences.

BURP 2.0: the Proposed CPMT

Proponents of the CPMT have effectively resurrected the BURP concept. The proposed CPMT is an alternative minimum tax (AMT) for corporations that is outside of the traditional income tax system. The proposed CPMT applies a lower tax rate (15% instead of 21%) to a potentially broader base (âadjusted financial statement incomeâ[4],[5] instead of tax reporting income). Only about 200 companies are expected to be affected[6] because the proposed CPMT is limited to companies that generate an average of $1 billion in âadjusted financial statement incomeâ over an applicable three-year period.[7]

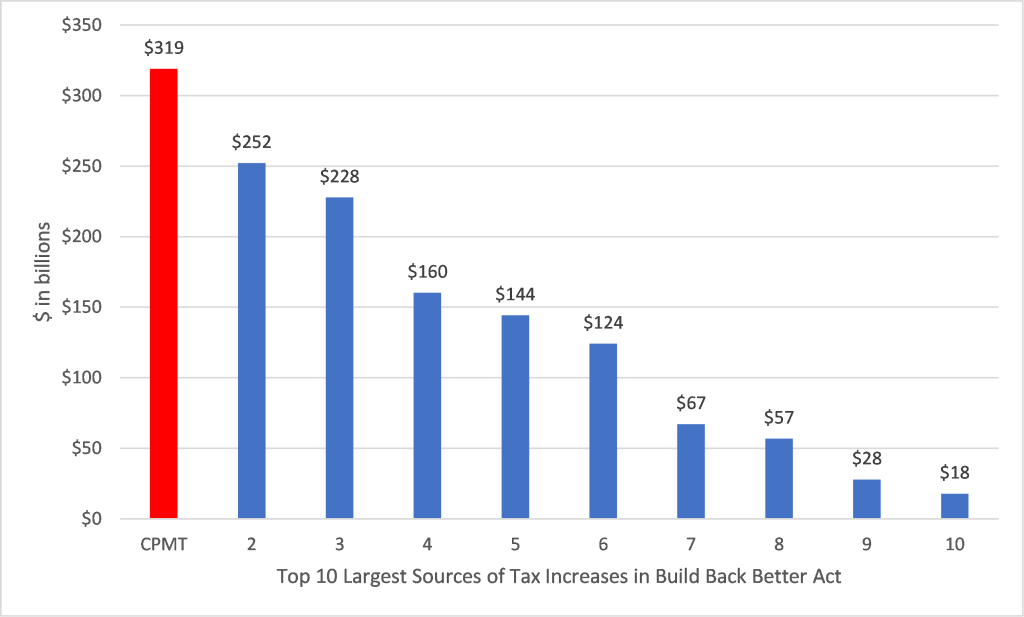

The proposed CPMT appears to be the largest single tax increase within the proposed Build Back Better Act. As shown in Figure 1, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated $319 billion for the proposed CPMT over the 10-year budget horizon, which is $67 billion greater than the next highest tax source of increases.

Figure 1: Taxes Raised Over 10 Year Period in Build Back Better Act[8]

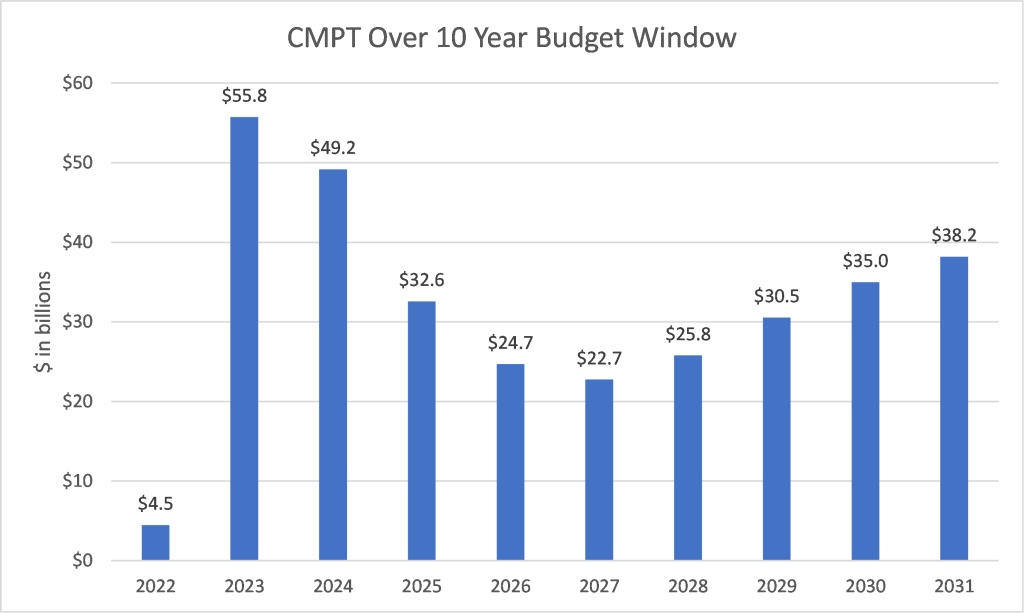

The year-by-year projection shows peak revenue for the proposed CPMT in its first full year of implementation. As shown in Figure 2, the Joint Committee on Taxation projects the proposed CPMT to decline from $55.8 billion in 2024 to $22.7 billion in 2027, then increase to $38.2 billion in 2031.

Figure 2: Year-by-Year Projection for Proposed CPMT[9]

Open Letter from Academics

An open letter signed by 264 âaccounting/tax scholarsâ highlights their concerns regarding the proposed CPMT.[10] They observe that there should be differences in pretax income between financial reporting and income tax applications because these applications serve different purposes. More specifically, financial reporting provides information related to a companyâs and its managersâ performance whereas income taxes are designed to raise revenue and encourage or discourage certain behaviors.

These academics believe use of financial reporting for income tax purposes is risky for three stated reasons. First, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) would effectively have some control over how much taxes a company pays. Second, potential politicization of the FASB could result in âlower qualityâ accounting standards and earnings for financial reporting purposes. Third, companies may âalter their reporting and report lower financial accounting earnings than they would in absence of this tax.â

How to Have Your Cake and Eat it Too: More Non-GAAP Measures

To paraphrase Saturday Night Liveâs âMore Cowbellâ skit, big companies want to report higher earnings and pay less taxes and the only prescription in a world with the proposed CPMT is more non-GAAP measures. Non-GAAP measures are a workaround from GAAP requirements because they allow a company to frame its performance in a different light. A company may be able have its cake (pay lower taxes via low GAAP profits) and eat it too (report higher profits via non-GAAP measures) if it can thread this needle.

This development would simultaneously eliminate and preserve the two sets of books. The two sets of books would technically be eliminated if GAAP and tax financial statements are the same. Nevertheless, the differences would be preserved if the âoldâ GAAP type results are reported within non-GAAP measures. As a practical matter, it would change from book #1 (GAAP) and book #2 (tax) to one set of books that has parts A (tax) and B (âoldâ GAAP).

Of course, such a development would neuter the proposed CPMT. Some (e.g., politicians who support the proposed CPMT) would be against such an outcome and others (e.g., politicians who do not support the proposed CPMT) would presumably prefer to just eliminate the proposed CPMT. However, it may be possible to foresee scenarios where the proposed CPMT remains but is rendered ineffective via politicization of the FASB.

It is also possible to foresee some middle ground. Companies already report non-GAAP measures. Perhaps there will be an increase in non-GAAP measures to offset some (but not all) GAAP changes made to result in big companies paying lower income taxes in a world with the proposed CPMT.

Note that this article contains the authorâs opinions, which are not the opinions of the authorâs employer.

[1] The tax code allows operating expenses (e.g., salaries) to be expensed when paid but requires capital expenses to be expensed over several years. As a result, the present value of the tax deduction is lower for capital expenses than operating expenses due to the time value of money.

[2] https://lawecommons.luc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1777&context=luclj at p. 23.

[3] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/before-the-bbb-there-was-the-burp-reviewing-the-u-s-experiment-with-book-taxes-in-the-1980s/.

[4] Some preferences within the tax code will be preserved.

[5] https://www.warren.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/MCG21C14.pdf.

[6] https://www.warren.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/senators-warren-king-and-wyden-announce-updated-proposal-to-prevent-the-biggest-and-most-profitable-corporations-from-paying-nothing-in-federal-taxes.

[7] https://www.warren.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/MCG21C14.pdf.

[8] Data from Joint Committee on Taxation, âEstimated Budgeted Effects of the Revenue Provisions of title XIII â Committee on Ways and Means, of H.R. 5376, The âBuild Back Better Act,ââ November 4, 2021, https://www.jct.gov/publications/2021/jcx-45-21.

[9] Data from Joint Committee on Taxation, âEstimated Budgeted Effects of the Revenue Provisions of title XIII â Committee on Ways and Means, of H.R. 5376, The âBuild Back Better Act,ââ November 4, 2021, https://www.jct.gov/publications/2021/jcx-45-21.

[10] https://tax.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Academic-Accounting-and-Tax-Open-Letter-on-Corporate-Profits-Tax.pdf.

Michael Vitti, CFA, joined Kroll(formerly Duff & Phelps) in 2005. Mr. Vitti is a Managing Director in the Morristown, NJ office and is a member of the Expert Services practice. He focuses on issues related to valuation and credit analyses across a variety of contested matters.

Mr. Vitti can be contacted at (973) 775-8250 or by e-mail to michael.vitti@kroll.com.