Intangible Property and Property Tax Appraisals

Part I of III

This article is the first of a three-part series on intangible property and property tax appraisals. Valuation analysts are often retained by industrial and commercial companies to assist with state and local property tax planning, compliance, and controversy matters. Often, analysts are retained by the legal counsel for the corporate taxpayers. This is particularly the case when the property tax matter involves an assessment appeal or litigation regarding the amount of the property assessment. The articles in this series focus on the valuation of intangible property within the context of ad valorem property tax disputes.

Introduction

Valuation analysts (hereinafter “analysts”) are often retained by industrial and commercial companies to assist with state and local property tax planning, compliance, and controversy matters. Often, analysts are retained by the legal counsel for the corporate taxpayers. This is particularly the case when the property tax matter involves an assessment appeal or litigation regarding the amount of the property assessment. This discussion focuses on the valuation of intangible property within the context of ad valorem property tax disputes. State and local assessment authorities often apply the unit principle of valuation to appraise industrial and commercial taxpayer property for ad valorem property tax purposes. The unit principle of valuation does not necessarily mean that the property is centrally assessed (i.e., assessed by a state-wide government agency). County and local assessors also apply the unit principle of valuation. The application of the unit principle (in contrast to the summation principle) of property valuation is primarily a function of the type of taxpayer and the type of taxpayer property.

Assessment authorities often apply the unit valuation principle to what are called utility-type properties. As will be described below, utility-type properties are not always public utilities. But these industrial and commercial and taxpayers often have certain characteristics that are similar to those of public utilities.

The issue with the application of the unit valuation principle is that the concluded unit value typically includes both (1) the value of the taxpayer’s tangible property (e.g., real estate and tangible personal property) and (2) the value of the taxpayer’s intangible property (e.g., working capital accounts, individual intangible property, general business goodwill). In many taxing jurisdictions, intangible property is not subject to property taxation. In such taxing jurisdictions, analysts and tax assessors have to (1) identify any intangible property included in the total unit value and (2) subtract that nontaxable property value from the total unit value. The result of that subtraction procedure is the value of the taxpayer’s taxable property. This intangible property identification and valuation process is the topic of this discussion.

This discussion is presented in three installments. Part one considers the following topics:

- Unit valuation definitions and principles

- Unit valuation principle standards and procedures

- Identification of intangible property

- Attributes of intangible property

- Part two considers the following topics:

- Intangible property valuation standards and procedures

- Extraction of the intangible property from the total unit value

- Illustrative example of a typical intangible property extraction method

- State and local assessment authorities often object to the analyst’s valuation of exempt intangible property. Part three recommends analyst best practices responses to assessor objections regarding intangible property valuations.

Unit Valuation Definitions

This discussion considers the identification, valuation, and extraction from the total unit value of exempt intangible property to conclude a taxable unit value for ad valorem property taxation purposes. Each of the clauses in the previous sentence is significant.

The first word to consider is identification. There is no single generally accepted list of all intangible property. Both analysts and tax assessors typically consider generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), income taxation, and authoritative appraisal literature as sources for intangible property listings. While there is not one single listing, there are general criteria for what is—and what is not—considered to be intangible property. These general criteria are discussed below.

The second word to consider is valuation. The appropriate standard of value applicable to any property tax assessment or appraisal is determined by the state statute. The standards of value included in the various state statutes may be similar; but there could be subtle differences between the different value definitions. Analysts and tax assessors typically value the taxpayer’s intangible property as part of the total unit of property. The definition of the subject unit’s highest and best use (HABU) is an important consideration in every property tax valuation.

The next word to consider is extraction. In taxing jurisdictions where intangible property is exempt from property taxation, the taxpayer’s intangible property value should be removed from the total unit value. The residual amount (i.e., total unit minus intangible property) generally indicates the value of the unit taxable property. The typical intangible property extraction formula is:

taxpayer’s total unit value

– exempt property value

= taxpayer’s taxable unit value

There are several generally accepted methods to make this exempt property extraction calculation. This discussion focuses on the most common of these methods: the direct extraction method.

The next phrase to consider is exempt property. The determination of what is (what is not) exempt property is an issue of state statute. The determination of what is and (what is not) exempt intangible property is also an issue of state statute.

The various statutory exempt intangible property listings may be descriptive, comprehensive, or illustrative. That is, some statutory listings just provide general descriptions of what an intangible property is. Some state statutes provide a specific list of six or eight or ten exempt intangible property types. And many state statutes indicate that intangible property “such as the following” (and include several examples) are exempt from property taxation. Unfortunately, these illustrative lists often create more controversy than they resolve. That is because they leave unanswered the question of what other intangible property are “like” the listed intangible property.

The next word to consider is intangible. The definition of intangible is something that cannot be seen or touched. The value of intangible property comes from the ownership rights associated with the property—not from the tangible elements of the property.

In the property tax discipline, the word “intangible” should be used as an adjective—not as a noun. As will be mentioned below, there are subtle (but important) differences between intangible property, intangible attributes, intangible influences, etc. However, these differences are lost if all of these intangible components are referred to as “an intangible”.

The next word to consider is property. The word property is a legal term. Property is typically considered a bundle of rights defined by federal or state statute.

The word asset is an accounting term. Assets are generally reported on an entity’s balance sheet prepared in accordance with GAAP. The asset recognition criteria are determined by the Financial Accounting Standards Board Statement of Concepts Number 6 (FASB CON 6).

Therefore, not all property types are reported as GAAP assets. And not all GAAP assets are considered to be legal property. It is important to note that the subject of a property tax appraisal is property—not assets. This statement is true whether the property tax appraisal is a unit principle valuation or a summation principle valuation.

The next phrase to consider is total unit value. The taxpayer’s total unit includes all of the property types encompassed in the unit valuation. Depending on the unit valuation methods applied by the analyst or the assessor, these property types include the following:

- Working capital accounts

- Real estate

- Tangible personal property

- Intangible personal property

- Regulatory and other accounts

- Intangible investment attributes

Some of these various property types may not be subject to property taxation in a particular taxing jurisdiction. Since property tax in all jurisdictions is imposed only on property actually in place, the total unit should only include property in existence on the valuation date.

The next phrase to consider is taxable unit value. The taxable unit should include only the property types that are subject to taxation in the taxing jurisdiction. There may be numerous types of statutory exemptions in the jurisdiction, including some (or all) of the taxpayer’s intangible property. The total unit value less the exempt property value equals the taxable unit value. Again, the taxable unit should only include property (tangible or intangible) actually in place on the valuation date.

The next word to define is ad valorem. Ad valorem is a Latin word meaning “according to the value”.

The applicable standard of value for property tax purposes is determined by state statute. In any property tax valuation, analysts and tax assessors should apply the same standard of value to all of the property types included in the total unit. All of the taxpayer property types should be appraised based on each property’s contribution to the total unit value. All of the taxpayer’s property types should be appraised based on the HABU concluded for the total unit.

The last term to consider is property taxation. The tax (and the appraisal itself) should be based on the value of the taxpayer’s property. That is, a property tax is not a tax on:

- Asset value,

- Income value,

- Business value, or

- Property owner value.

Fundamentals of the Unit Principle Valuation

The unit principle of property valuation is not unique to property taxation. For example, application of the “unit rule” is required for all property appraisals developed in compliance with both the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP) and the Uniform Appraisal Standards for Federal Land Acquisitions (UASFLA).

The unit principle of valuation appraises a bundle of different types of property as a single “unit”. In the case of a property tax valuation, some of the property types included in the taxpayer unit valuation may not be subject to property tax in the subject taxing jurisdiction. The ultimate objective of the unit principle valuation developed for property tax purposes is to appraise the taxpayer’s taxable unit of property.

Most taxpayers subject to the unit principle of valuation own utility-type property. These properties are special-purpose and typically income-producing. These properties are physically, functionally, and economically integrated. These properties operate as an integral component of a going concern business enterprise. That is, these properties generate business operating income—not property rental income. When such properties sell, they typically sell as a bundle (or unit) of property. And they typically transfer as part of the sale of the overall business enterprise.

Typical examples of such taxpayers (and such utility-type properties) include: railroads, airlines, interstate pipelines, electric generation and distribution properties, telecom properties, cable TV systems, water and wastewater systems, and many others. Other examples of properties that may be subject to the unit principle of property valuation includes: mines, marinas, racetracks, hospitals, nursing homes, and many others.

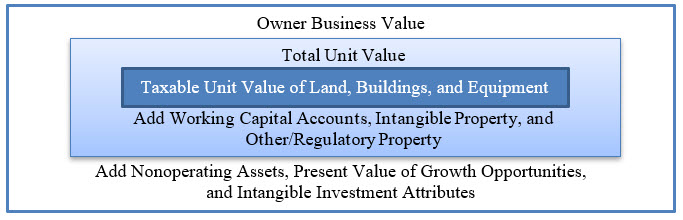

For many utility-type property owner/taxpayers, Figure 1 illustrates the typical differences between the owner’s total business value, the total unit value, and the taxable unit value.

Figure 1: Relationship of Owner Business Value, Total Unit Value, and Taxable Unit Value

The objective of the unit principle of property valuation is to conclude the value of the unit (or bundle) of property subject to taxation. If the unit value includes other property categories (such as intangible property or intangible attributes), then adjustments may have to be made to the unit value conclusion.

For most utility-type property owner/taxpayers (in a jurisdiction that does not tax intangible property), Figure 2 indicates the typical relationship between the various property categories that may be captured in the unit principle valuation.

Figure 2: Relationship of Owner Business Value, Total Unit Value, and Taxable Value

|

Taxable Unit Value = |

Land, Buildings, and Equipment |

||

|

Total Unit Value = |

Taxable Unit Value |

Plus |

Working Capital Accounts, Intangible Property, and Other/Regulatory Property |

|

Owner Business Value = |

Total Unit Value |

Plus |

Nonoperating Property, Present Value of Growth Opportunities, and Intangible Investment Attributes |

For property tax purposes, it is typically appropriate to develop a unit principle valuation (sometimes called a utility principle valuation) when:

- The property is physically, functionally, and economically integrated

- The property crosses multiple taxing jurisdictions

- The HABU of the property is based on an assumption of one physical unit

- There is a continuous process flow where physical components cannot function independently

- The taxpayer does not maintain financial or operational statements for a smaller unit of property

- The property components operate as a going concern business operation

- The unit derives income through the sale of goods or services—not from property rental income

- The property would sell as one single unit

- Any comparable sales transaction data involve the sales of going concern business units

- There is a statutory requirement to value the subject property by applying the unit valuation principle

When is a Property Appraisal a Unit Principle Valuation?

Tax assessors and analysts may not realize that the appraisal they are developing is based on the unit valuation principle. Assessors and analysts should understand that the property appraisal de facto is a unit principle valuation depending on how the analyst applies the generally accepted property appraisal approaches and methods.

For example, the appraisal is a unit principle valuation if in the application of the income approach appraisal methods:

- The income subject to capitalization is business operating income and not property rental income

- The income subject to capitalization includes some income from future property that is not yet in place on the valuation date

- The capitalization rate is based directly on capital market pricing data or capital market rate of return data

The appraisal is a unit principle valuation if in the application of the market approach appraisal methods:

- The income subject to the market-derived pricing multiples includes business operating income

- The market-derived pricing multiples are extracted from stock market prices

And, the appraisal is a unit principle valuation if in the application of the cost approach appraisal methods:

- Any property economic obsolescence is measured on an aggregate basis

- The property economic obsolescence income metric is business operating income

- Any economic obsolescence comparative benchmark metrics are based on capital market rate of return or capacity data

Generally Accepted Unit Principle Valuation Approaches and Methods

There are generally accepted unit principle valuation approaches and methods. These approaches and methods are listed below:

- Cost approach

- Replacement cost new less depreciation (RCNLD) method

- Reproduction cost new less depreciation (RPCNLD) method

- Historical cost less depreciation (HCLD) method

- Market approach

- Stock and debt method

- Direct sales comparison method

- Income approach

- Yield capitalization method

- Direct capitalization method

There are generally accepted valuation procedures applied within each valuation method. There is a body of literature that documents these generally accepted unit principle valuation approaches and methods. A description of each of these valuation approaches and methods is beyond the scope of this discussion.

The names of the unit principle valuation approaches and methods are very similar to the names of the more familiar summation principle valuation approaches and methods. Analysts should not be confused by these similarities. There are important differences between the two types of property valuations at the procedural (or actual application) level. And there are important differences between the two types of property valuations with regard to the analyst’s selection of the specific valuation variables within each method applied.

When Intangible Property is Included in the Unit Valuation

The value of the taxpayer’s intangible property may be included in the unit principle valuation depending on the analyst’s application of the property appraisal approaches. For example, intangible property may be included in the income approach when either (1) the owner’s business operating income (related to delivering goods and services) is used or (2) the owner’s business cost of capital (WACC) components are used in the yield capitalization method or the direct capitalization method.

Intangible property may be included in the market approach when either (1) the market-driven pricing multiples are extracted from the sales of going concern businesses or (2) the market-derived pricing multiples (or direct capitalization rates) are extracted from capital market data.

Finally, intangible property may be included in the cost approach when either (1) there is economic obsolescence in the total unit or (2) the economic obsolescence measurements analysis does not assign a fair rate of return to the value of the taxpayer unit’s intangible property.

Intangible Property Exemption in the Taxing Jurisdiction

The fundamental question that both the analyst and the tax assessor have to address is: what type of property is considered to be exempt intangible property in the taxing jurisdiction? The answer to the fundamental question depends on the relevant statutory authority, judicial precedent, and administrative rulings. Analysts should understand that, in answering this question regarding intangible property, state and local taxing authorities are not bound by either GAAP authority or federal income tax authority.

The criteria for exemption from state and local property taxation may vary by jurisdiction. And, depending on the jurisdiction, the exempt intangible property may include both intangible personal property and intangible real property.

The next question that the analyst and the tax assessor have to address is: does the unit valuation include the value of any intangible property? Intangible property values should be removed from the unit value if and only if two conditions are met: (1) the intangible property category is exempt from property taxation in the subject jurisdiction and (2) the intangible property value is encompassed in the unit value conclusion. So, the answer to the question “does the unit value conclusion include intangible property” depends on several factors including:

- The unit valuation approaches and methods applied by the analyst

- The specific unit valuation variables selected by the analyst

Accordingly, analysts who develop unit principle valuations should:

- Receive legal instructions as to if (and which) intangible property categories are exempt from property taxation

- Determine if the total unit value conclusion was developed in a way that includes exempt intangible property

What is an Intangible Property?

Again, the term “intangible” means something that lacks physical substance. The adjective “intangible” means that the economic benefit of the property does not come from its physical substance. Rather, the intangible property value is based on the rights and privileges to which the property entitles the owner/operator.

Typically, intangible property should have the following attributes:

- It should be subject to a specific identification and recognizable description

- It should be subject to legal existence and legal protection

- It should be subject to the rights of private ownership, and that private ownership should be transferrable

- There should be some tangible evidence or manifestation of the existence of the intangible property

- It should be created or come into existence at an identifiable time or as the result of an indefinable event

- It should be subject to being destroyed or to a termination of existence at an identifiable time or as the result of an identifiable event

In summary, there should be a specific bundle of legal rights associated with the intangible property. However, analysts and tax assessors should not create their own conditions or criteria for what qualifies as an intangible property. For example, the list of criteria recommended above indicates that intangible property should be transferrable. It does not indicate that the intangible property should be transferrable independently from any other property. In other words, it allows for the transaction where the intangible property is transferred either with tangible property or with other intangible property. Any state can develop a statute that requires additional criteria (like transferability independent of other property). But such additional criteria then became a legal matter—not a matter of analyst judgement or opinion.

ASC Topic 805 Recognition Considerations

The topic of transferability of intangible property is addressed in both the appraisal literature and in the accounting literature. Once source of guidance for property tax professionals is U.S. GAAP. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) Accounting Standards Certification (ASC) 805 Business Contributions specifically addresses the issue of intangible property transferability.

The FASB ASC topic 805-30-20 glossary defines an identifiable intangible asset as follows:

Identifiable Intangible Assets

The acquirer recognizes separately from goodwill the identifiable intangible assets acquired in a business combination. An intangible asset is identifiable if it meets either (1) the separability criterion or (2) the contractual – legal criterion described the definition of “identifiable”.

The FASB ASC topic 805-30-20 glossary defines the term identifiable as follows:

Identifiable

An asset is identifiable if it meets either of the following criteria:

- It is separable, that is capable of being separated or divided from the entity and sold, transferred, licensed, rented, or exchanged, either individually or together with a related contract, identifiable asset, or liability, regardless of whether the entity intends to do so.

- It arises from contractual or other legal rights, regardless of whether those rights are transferable or separable from the entity or from other rights and obligations.

Therefore, according to GAAP, an intangible property should be transferable in order to be recognized by an acquirer in a business combination transaction. However, that intangible property may be transferable either (1) separately (meaning individually, by itself) or (2) in a bundle of property—with tangible property or with other intangible property.

Tangible Evidence of Intangible Property

The value of intangible property comes from its non-physical elements. In contrast, the value of tangible property comes from its physical elements. Analysts understand that the tangible evidence of intangible property does not convert that property into tangible property. This statement is true because the tangible evidence does not affect the value of that property.

Summary

This first of this three–part series considers what analysts need to know about ad valorem property tax definitions, standards, and practices. Analysts are often retained by industrial and commercial taxpayers to value and to extract intangible property from the tax assessor’s total unit value conclusion. Part two of this discussion will continue with a discussion of generally accepted intangible property identification, valuation, and extraction procedures.

The opinions and materials contained herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of the author’s employer. In authoring this discussion, neither the author nor Willamette Management Associates, a Citizens Company, is undertaking to provide any legal, accounting or tax advice in connection with this discussion. Any party receiving this discussion must rely on its own legal counsel, accountants, and other similar expert advisors for legal, accounting, tax, and other similar advice relating to the subject matter of this discussion.

Robert F. Reilly, CPA, ASA, ABV, CVA, CFF, CMA is a retired former Managing Director of Willamette Management Associates. He lives in Chicago and continues to consult in areas of his previous practice that included business valuations, forensic analysis, and financial opinion service.

Mr. Reilly can be contacted at (847) 207-7210 or by e-mail to robertfreilly.cpa@gmail.com.