Intangible Property and Property Tax Appraisals

Part II of III

This article is the second of a three-part series on intangible property and property tax appraisals. Valuation analysts are often retained by industrial and commercial companies to assist with state and local property tax planning, compliance, and controversy matters. Often, analysts are retained by the legal counsel for the corporate taxpayers. This is particularly the case when the property tax matter involves an assessment appeal or litigation regarding the amount of the property assessment. The articles in this series focus on the valuation of intangible property within the context of ad valorem property tax disputes.

Introduction

This discussion is part two of a three-part series. Many state and local tax authorities apply the unit principle of valuation to value the property of utility-type industrial and commercial taxpayers. The unit valuation conclusions often include the value of both (1) taxpayer tangible property and (2) taxpayer intangible property. In taxing jurisdictions that do not tax intangible property, valuation analysts (“analysts”) are often retained to identify, value, and extract the tax–exempt intangible property.

This part of the discussion presents (1) several listings of intangible property, (2) summaries of the generally accepted intangible property valuation approaches and methods, and (3) explanations and examples of the generally accepted intangible property extraction methods.

Examples of Intangible Property: Internal Revenue Code Section 197

As mentioned in part one of this series, there is no single generally accepted list of intangible property for property taxation purposes. Therefore, analysts often rely on listings of intangible property developed for GAAP, federal income taxation, or other regulatory purposes. For example, analysts often rely on the list of “Section 197 intangible assets” presented in the Internal Revenue Code. The complete listing of Section 197 intangible assets is presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Section 197 Intangible Assets

- Goodwill

- Going-concern value

- Any of the following intangible items:

- Workforce in place including its composition and terms and conditions (contractual or otherwise) of its employment

- Business books and records, operating systems, or any other information base (including lists or other information with respect to current or prospective customers)

- Any patent, copyright, formula, process, design, pattern, know-how, format, or other similar item

- Any customer-based intangible

- Any supplier-based intangible

- Any other similar item

- Any license, permit, or other right granted by a governmental unit or an agency or instrumentality thereof

- Any covenant not to compete (or other arrangement to the extent such arrangement has substantially the same effect as a covenant not to compete) entered into in connection with an acquisition (directly or indirectly) of an interest in a trade or business or substantial portion thereof

- Any franchise, trademark, or trade name

Examples of Intangible Property: Treasury Regulation 1.482-4

Analysts also rely on the listing of intangible property presented in the Treasury Regulations related to Internal Revenue Code Section 482. These regulations specifically use the term “intangible property”. A complete listing of the Regulation 1.482-4 intangible property is presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Regulation 1.482-4 Intangible Property

- Patents, innovations, formulas, processes, designs, patterns, or know-how;

- Copyrights and literary, musical, or artistic compositions;

- Trademarks, trade names, and brand names;

- Franchises, licenses or contracts;

- Methods, programs, systems, procedures, campaigns, surveys, studies, forecasts, estimates, customer lists, or technical data; and

- Other similar items;

- For purposes of section 482, an item is considered similar if it derives its value from its intellectual content or other intangible properties.

Intangible Property Valuation Approaches and Methods

Analysts understand that there are generally accepted intangible property valuation approaches and methods. The various valuation methods can be categorized within these generally accepted property valuation approaches: the cost approach, the market approach, and the income approach. The most frequently applied intangible property valuation methods are listed in Table 3.

Table 3: Intangible Property Valuation Approaches and Methods

- Cost approach methods

- Replacement cost new less depreciation (RCNLD) method

- Reproduction cost new less depreciation (RPCNLD) method

- Trended historical cost less depreciation (THCLD) method

- Market approach methods

- Relief from royalty (RFR) method

- Comparable uncontrolled transaction (CUT) method

- Comparable profit margin (CPM) method

- Income approach methods

- Differential income (with/without) method

- Incremental income method

- Greenfield method

- Profit split method (or residual profit split method)

- Disaggregated method

- Distribution method

- Residual (or excess) income method

- Capitalized excess earning method (CEEM)

- Multiperiod excess earnings method (MEEM)

A description of each one of the generally accepted intangible property valuation methods is beyond the scope of this discussion. However, analysts understand that there are generally accepted valuation procedures that are applied within each valuation method. That is, intangible property valuation procedures role up into valuation methods. And, intangible property valuation methods role up into valuation approaches.

There is a body of professional literature that documents these generally accepted, intangible property valuation approaches and methods. In addition, there are valuation professional standards related to intangible property. These intangible property-specific professional standards include the relevant sections of the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practices (issued by the Appraisal Foundation), the Statement on Standards for Valuation Services (issued by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants), and the International Valuation Standards (issued by the International Valuation Standards Council).

Intangible Property Fair Value Measurement Guidance

There is specific professional guidance related to intangible property fair value measurements developed for GAAP financial accounting purposes. This guidance includes the FASB ASC topic 805, Business Combinations mentioned above. This guidance also includes ASC topic 820 Fair Value Measurements. In addition, the Mandatory Performance Framework and the Application of the Mandatory Performance Framework for the Certified in Entity and Intangible Valuations Credential provide specific guidance regarding intangible property valuations developed for financial accounting purposes. The Application includes specific professional guidance related to the following intangible property-related topics:

- Application of the tax amortization benefit (TAB) value adjustment

- Derivation of the present value discount rate

- Application of valuation discounts and premiums

- Useful economic life measurement methods and procedures

- Assembled workforce valuation

- Reconciliation of alternative intangible property value indications

The above-mentioned guidance relates primarily to financial accounting-related intangible property valuations. However, analysts may also derive useful insights from these professional guidance sources with regard to intangible property valuations developed for property tax purposes.

Intangible Property Cost Approach Valuation

Many analysts apply the cost approach to value the intangible property included in the unit principle valuation. These analysts often express a preference for the application of the cost approach with regard to the valuation of contributory intangible property. Contributory intangible property is not customer-facing and typically does not generate a separately measurable stream of operating income. Typical examples of contributory intangible property include computer software, engineering drawings and technical documentation, procedural and training manuals, and a trained and assembled workforce. Accordingly, a few comments regarding the application of the cost approach may be helpful.

First, the cost approach may be applicable when income approach and/or market approach data are not available with regard to the subject intangible property.

Second, certain types of intangible property lend themselves to the application of the cost approach. Example of these intangible property types include:

- Recently developed (relatively new) intangible property

- Intangible property that is fungible or may be easily exchanged or substituted

- Intangible property for which the owner/operator’s historical development cost data are still available

Third, when applying the cost approach, analysts should consider whether there are sufficient reliable data available regarding the subject intangible property to estimate:

- A current cost measurement (such as replacement cost new or reproduction cost new) and

- All forms of deprecation and obsolescence (including economic obsolescence)

- An obsolescence estimate that may involve same analysis of the useful economic life (UEL) of the subject intangible property.

Intangible Property and the Unit Valuation Cost Approach

In the belief that such reliance will mitigate the requirement for an intangible property valuation, some analysts recommend heavy reliance on the unit valuation cost approach. These analysts propose that the taxpayer’s intangible property is not captured in a cost approach unit value indication. Therefore, these analysts suggest, the taxpayer’s intangible property value does not need to be extracted from the cost-based unit value indication. However, this rationale is fundamentally flawed!

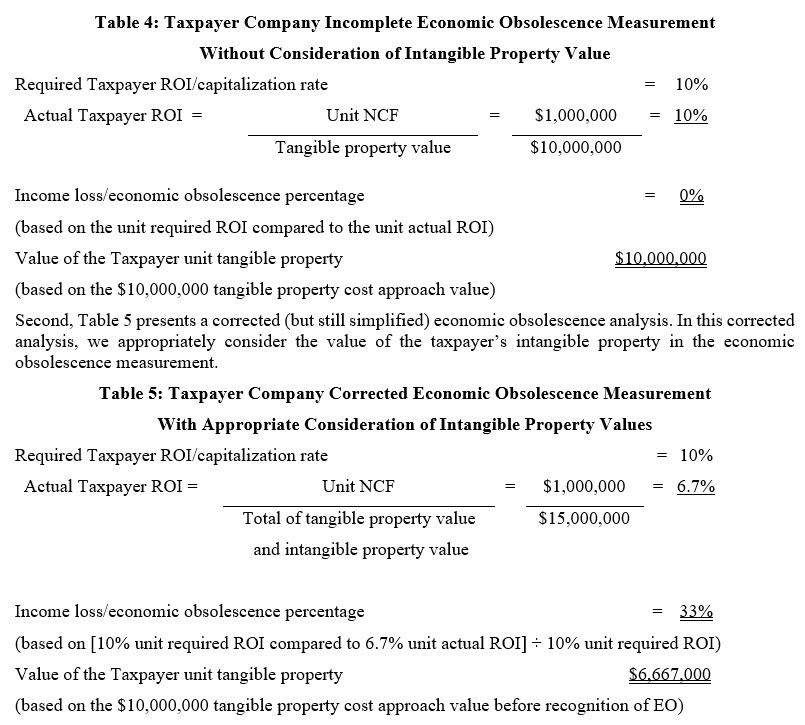

These analysts ignore the very important fact that the taxpayer’s intangible property value should be considered in the unit valuation cost approach economic obsolescence (EO) analysis. The following simplified example illustrates the impact of considering intangible property value in the measurement of economic obsolescence in the unit valuation cost approach. In this illustrative example, let’s assume that the taxpayer unit is located in a taxing jurisdiction where only tangible property is subject to property taxation.

Let’s assume the following hypothetical Taxpayer Company (“Taxpayer”) unit fact set:

- Taxpayer tangible property value—based on a cost approach analysis $10,000,000

- Taxpayer intangible property value—based on a cost approach analysis $5,000,000

- Taxpayer total unit net cash flow (NCF) $1,000,000

- Taxpayer unit required return on investment (ROI)/capitalization rate 10%

First, Table 4 illustrates a simplified economic obsolescence analysis; without considering the value on the taxpayer’s intangible property in the economic obsolescence measurement.

As can be seen from comparing Table 4 and Table 5, the consideration of a taxpayer’s intangible property is an important procedure in any unit valuation cost approach analysis. Excluding consideration of the taxpayer’s intangible property value can lead to an incomplete economic obsolescence measurement; and to an overstated cost approach unit value indication.

Typical Procedures to Extract Exempt Property from the Unit

The procedures that may be applied to extract non-taxable intangible property value from the total unit value are essentially the same procedures that analysts apply to extract non-taxable tangible property value from the total unit value. Therefore, first let’s consider the typical procedures applied to extract exempt tangible property from the total taxpayer unit value. Second, let’s consider the typical procedures applied to extract exempt intangible property from the total taxpayer unit value. It is noteworthy that, by statute, many jurisdictions exempt various specialized property categories from ad valorem taxation. These various specialized property categories that are exempt from taxation may include:

- Working capital (cash, marketable securities, receivables)

- Construction in progress

- Locally assessed property

- Pollution abatement equipment

- Over-the-road vehicles

- Other property categories

The values for these exempt property categories are often determined by a formula that is set by statute or regulation. Some of the typical valuation formula that apply to these exempt property categories may include:

- Historical cost less depreciation (HCLD)

- Market value to book value ratio X HCLD

- Other formula

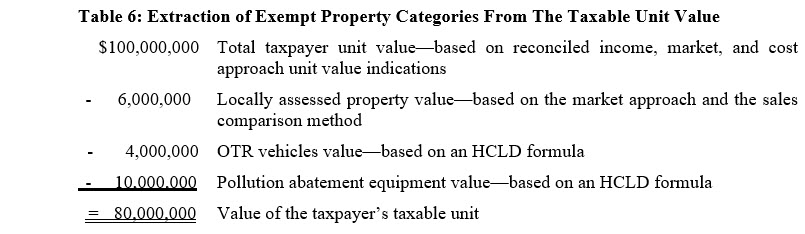

Let’s consider a simple example to illustrate the typical procedure to extract (or remove) the value of exempt property from the total taxpayer unit value. In this illustrative example, let’s assume a centrally assessed unit of property in the State of Taxalot. Let’s assume that the total reconciled unit value is $100,000,000. This value is based on a synthesis of income approach, market approach, and cost approach unit value indications.

The value of a locally assessed office building (property that is included in the total unit value) is $6,000,000. This value is based on the market approach and the sales comparison method. The value of the unit’s over-the-road vehicles (that are exempt from property taxation) is $4,000,000. This value is based on the application of a statutory historical cost less depreciation formula. The value of the unit’s pollution abatement equipment (that is exempt from property taxation) is $10,000,000. This value is based on the application of a statutory historical cost less depreciation formula. Now, the relevant question is: what is the value of the taxable unit of property?

The taxable unit value (after consideration of all exempt property categories) would be typically calculated as presented in Table 6.

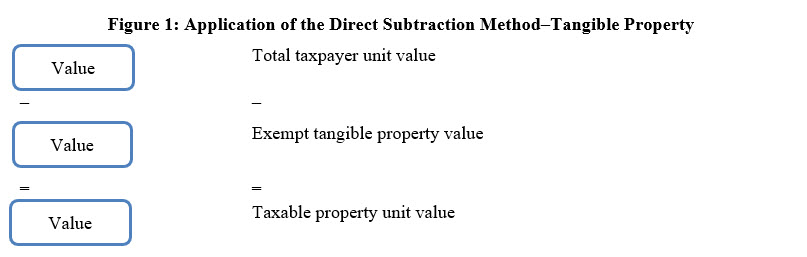

The extraction procedure illustrated in Table 6 is typically called the direct subtraction method. This method is the most typically applied property extraction method for adjusting a total unit value into a taxable unit value.

Tangible Property Extraction Direct Subtraction Method

The typical procedures for the application of this direct subtraction method with regard to exempt tangible property is illustrated in Figure 1:

As illustrated in this figure, value (of exempt tangible property categories) is subtracted from value (of the total taxpayer unit) to conclude value (of the taxable unit of property). The subtractions (and any additions) are always made on a reconciled value to reconciled value basis; and not on an individual valuation approach (e.g., cost approach) indication to individual valuation approach (e.g., cost approach) indication basis.

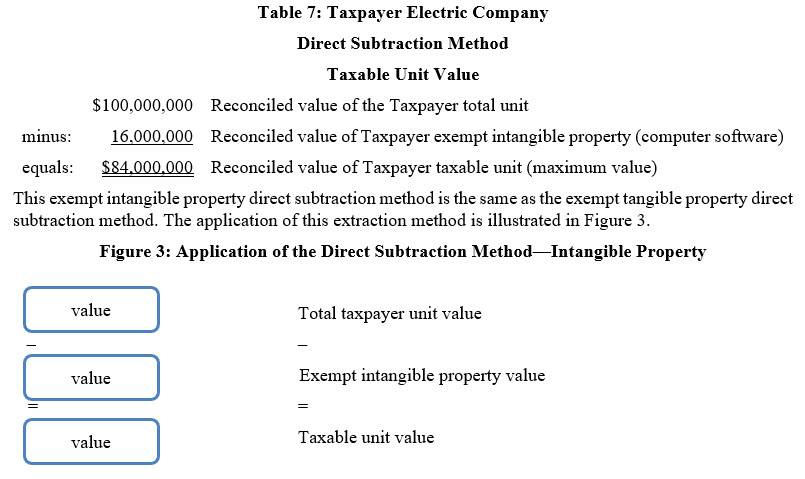

Intangible Property Extraction Procedures

There are three methods that analysts typically apply to extract intangible property value from the total unit value:

- Direct subtraction method

- Transfer price (income allocation) method

- Royalty rate method

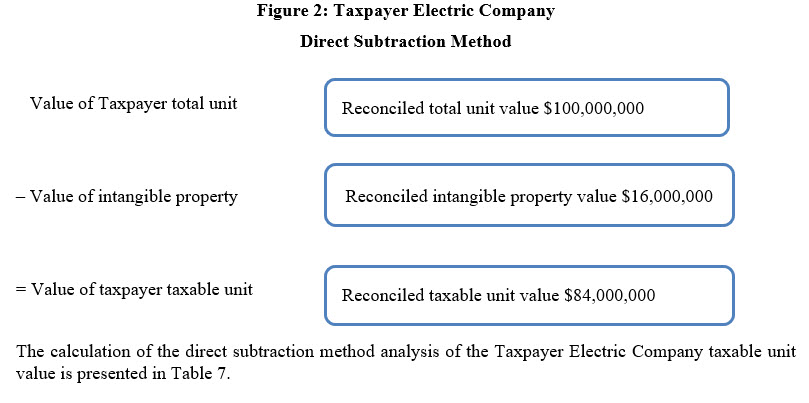

As with the extraction of exempt tangible property, the direct subtraction method is the most typically applied method to extract the exempt value. That is, to extract exempt intangible property from the total unit value, the direct subtraction method is essentially the same procedure that is typically applied to extract the value of exempt tangible property from the total unit value.

The direct subtraction method is based on the following simple formula:

Reconciled value of the total unit (based on any/all unit principle valuation approaches)

minus: reconciled value of exempt intangible property (based on any/all intangible property valuation approaches)

equals: reconciled value of the taxable unit of property

Based on the above formula, the residual taxable unit value often represents a maximum value indication. That is because the residual value may include same nontaxable property categories that were not specifically identified and extracted from the total unit value.

Intangible Property Extraction Example

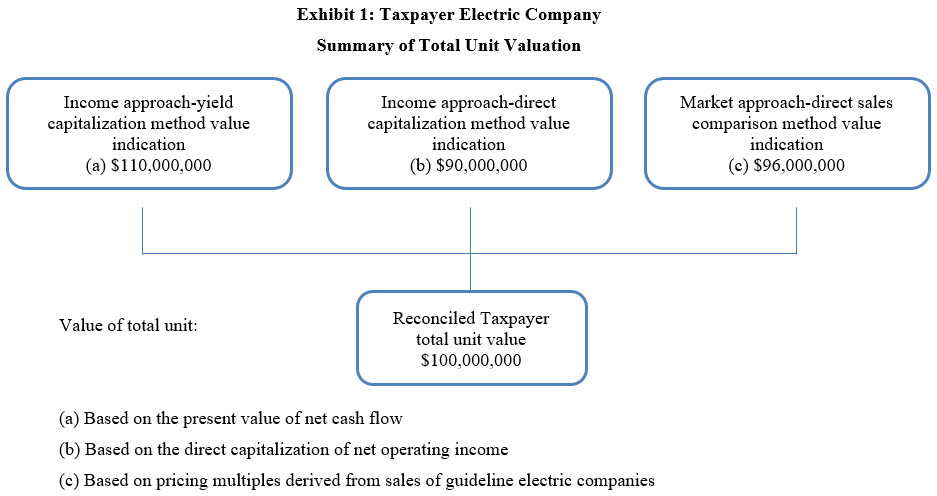

Let’s consider a simple intangible property extraction example. An analyst values the Taxpayer Electric Company (“Taxpayer”) total unit at $100,000,000 in the State of Taxalot. The analyst applied several income approach and market approach unit valuation methods to conclude the total unit value. This unit valuation process is summarized in Exhibit 1.

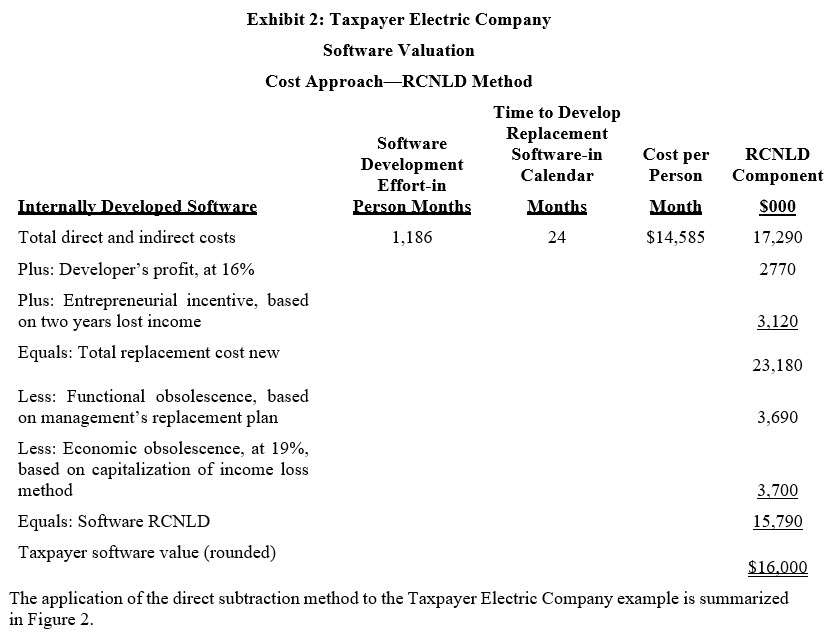

Internally developed computer software is an important intangible property at Taxpayer. Intangible property is exempt from property taxation in the State of Bliss. The analysts values the computer software at $16,000,000. The analyst applied the cost approach and the replacement cost new loss depreciation (RCNLD) method to value the Taxpayer computer software. This valuation analysis is summarized in Exhibit 2. To simplify this example, let’s ignore all other exempt intangible property.

In the direct subtraction method, the exempt property additions and subtractions are always made on a reconciled value (e.g., total intangible property) to reconciled value (e.g., total unit value) level; and not a valuation approach (e.g., cost approach value) indication to valuation approach (e.g., cost approach value) indication level.

Summary

This article of this three–part series summarized what analysts need to know about the identification, valuation, and extraction of exempt intangible property within the context of an industrial or commercial taxpayer’s ad valorem property tax assessment or appeal. Analysts are often retained by utility-type industrial or commercial companies (or by their legal counsel) to assist with such state or local property tax appeal or litigation matters.

The third and final part of this series considers that state and local tax assessors often object to such intangible property valuations. The next part of our discussion suggests analyst best practices responses to the most typical of these tax assessor objections.

The opinions and materials contained herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of the author’s employer. In authoring this discussion, neither the author nor Willamette Management Associates, a Citizens Company, is undertaking to provide any legal, accounting or tax advice in connection with this discussion. Any party receiving this discussion must rely on its own legal counsel, accountants, and other similar expert advisors for legal, accounting, tax, and other similar advice relating to the subject matter of this discussion.

Robert F. Reilly, CPA, ASA, ABV, CVA, CFF, CMA, is a retired former Managing Director of Willamette Management Associates. He lives in Chicago and continues to consult in areas of his previous practice that included business valuations, forensic analysis, and financial opinion service.

Mr. Reilly can be contacted at (847) 207-7210 or by e-mail to robertfreilly.cpa@gmail.com.