Accidental Brokers

And How the IRS Unravels Contract Law in its Newest Cryptocurrency Proposals

This article details the issues with the proposal put forth by the IRS related to cryptocurrency transaction reporting and identifies the actionable bits of information that may be useful to practitioners. This article also covers proposed rules expanded definition of a broker and whom the new regulation will cover along with the what and whys; a second article will cover the how.

This article details the issues with the proposal put forth by the IRS related to cryptocurrency transaction reporting and identifies the actionable bits of information that may be useful to practitioners.[1] Namely, the focus on fair market value (FMV) throughout the IRS proposal may offer job security to valuation professionals and the undermining of contract law may offer job security to litigation professionals. To take advantage, practitioners need to stay abreast of pending regulations and learn how to apply their skills to new asset classes. This article will cover the what and the why; a second article will cover the how.

The IRS released a convoluted proposal for public comment in the middle of last year and heard a dozen crypto and tax professionals provide their comments by telephone in November 2023. The proposal drew substantial criticism from tax practitioners and crypto services providers; it highlights the regulator’s lack of basic knowledge related to complex cryptocurrency transactions, such as decentralized exchanges. Perhaps, as a centralized regulating entity, the IRS cannot fathom software-based decentralization some 10 years after the Ethereum blockchain emerged (where defi largely began). As a result, maybe the IRS harbors the misplaced belief that surely someone must be in charge of the exchange and whom they can issue a John Doe summons; this belief is false, and the IRS remains misguided in its approach to complex transactions, if the public commenters are to be believed. In fact, the comments are harsh and paint the IRS as nothing more than a child flailing in his futile attempts to grab a cookie jar placed just outside the centralized authority’s reach and whining about the crumbs he receives from centralized exchanges like Coinbase (who respond to John Doe summons’). However, the public comments amount to a collective, “don’t create more work for us” whine of their own.

Coinbase offered a 14-page letter detailing its “serious concerns about the nature and scope” of the proposal, specifying that, as written, the proposal would “impose an unprecedented, unchecked, and unlimited tracking on the daily lives of Americans.” Those are fine words from the U.S. based exchange known for cooperating with the U.S. government and its sole-source crypto data aggregator, Chainalysis.

Secretary Yellen chimed in with the “proposed rule will align the crypto industry with every other financial industry in the United States by subjecting brokers to standard tax reporting requirements,” claiming that the rules simply require brokers to provide a 1099 to users so they can file taxes and require brokers to provide that information to the IRS so the IRS can track down “would-be tax avoiders”. This claim is wildly misguided because it implies that the entire crypto industry is somehow subject to the U.S. regulatory agency. When did the IRS become a policing agent of “would-be tax avoiders” in the world? Tax evasion is illegal; tax avoidance appears to be a goal among taxpayers in general. In fact, tax avoidance underpins most of the marketing for tax automation software. The first ad for a TurboTax search on the internet is “Turbo Tax – Official Site – Maximum Refund Guaranteed”.

One commenter summed up the confusion created by the IRS: “If a broker does not know they are a broker, are they still a broker?” This is an interesting defense for all the unlicensed securities actions out there, “Your honor, I didn’t know I was supposed to register as a broker to sell these things that I also didn’t know were securities.” I do not see that defense playing well with any state’s securities regulator, but this comment reflects the absurdity and lack of clarity inherent in the proposal.[2] It also highlights the dismissal by the IRS of the SEC’s recent opinions in their entirety. Recently, federal courts decided that not all cryptocurrency sales are akin to securities and thus do not fall under securities and broker regulations; the IRS did not get this memo.

Most of the concern from commenters centered around how to tell if you are a broker to determine your reporting requirements and there is no good answer in the proposal, nor was there a good answer on the call where the IRS mainly asked more questions. The National Taxpayer Union Foundation complained about the IRS attempting to apply its early 20th century framework to this new, wholly digital currency and details the issues of requiring this new global ecosystem to comply with centralized U.S. regulatory mechanisms.[3] Among all the complaints from public commenters, and there are many, the accidental broker dilemma and the valuation recommendations drew the most concern. Overall, most of the commenters begged for either a new entity for crypto enforcement, a new division within the IRS for new enforcement, and the removal of any new reporting mechanisms whatsoever.

There is still some actionable information in the near 300-page proposal and that is the focus on FMV, a mechanism known and loved by valuation practitioners everywhere. The IRS attempts to define what exactly a “sale” is within cryptocurrency and attempts to specify the inventory method that crypto holders should use (without calling it that of course, which would draw even more criticism). “If a holder does not specifically identify the units to be sold, disposed of, or transferred, the units in the wallet or account disposed of are determined in order of time from the earliest purchase date of the units of that same digital asset. For purposes of making this determination, the dates the units were transferred into the taxpayer’s wallet or account are disregarded.”[4]

This statement suggests the IRS is proposing a requirement to use FIFO by default for all assets held in a portfolio (distinct from a single address, wallet, or exchange account) and is an attempt to prevent the transfer of crypto from one wallet to another just to claim a cost basis more recent to the sale date.[5] If a user does have sufficient documentation, the user can specify his own basis method: earliest acquired (FIFO), latest acquired (LIFO), or highest basis (not a recognized accounting method). This specification occurs with each sale, disposition, or transfer and has no bearing, according to the IRS, on the taxpayer’s accounting method. The IRS goes on to propose that when a broker accepts a transfer of crypto from a user, the broker should also collect all basis information from that user (a suggestion at which Coinbase fell on the floor, kicked, and screamed).[6]

Calculation for the Amount Realized

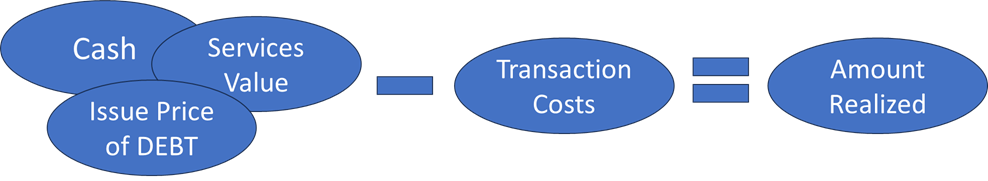

Proposed § 1.1001–7(b)(1)(i) provides the general rule for determining the amount realized on a sale or disposition of digital assets for cash, other property differing materially either in kind or in extent, or services. Under these rules, the amount realized is the sum of:

- The cash received;

- The FMV of any property received (including digital assets) or the issue price of a debt instrument (if that is being exchanged under § 1.1001–1(g)); and

- The FMV of any services received;

all reduced by the allocable digital asset transaction costs.

The simplified graphic illustrates the proposal put forth by the IRS. There is a glaring exclusion and that is the contract price at which a service was performed.

If you thought the IRS was trying its best, this method for amount realized illustrates its attempted overreach. If you pay your lawn guy in Chuck E. Cheese tokens, he does not report the FMV of the Chuck E. Cheese tokens, he reports the contractual cost of the lawn services provided, as the amount realized. That value is different from “FMV” by definition, although in some cases, the amount may be the same. The IRS disagrees and puts the onus on the taxpayer to calculate the FMV of the Chuck E. Cheese tokens at the time of transfer (for every transfer) and dictates that any contract for services rendered be disregarded altogether. This is more work (i.e., time and money) for the taxpayer and more work (time and taxpayer’s money) for the IRS to account for the difference between the contract price and the price of children’s tokens, a negligible difference at best.

Accidental Broker

In its proposal, the IRS redefines a broker so broadly that many lay individuals within the crypto space and a lot of automated software would find itself with a sudden requirement to gather and report data to customers and to the IRS. The IRS defines broker such that anyone indirectly involved in the crypto space may be a broker, which drew criticism from most commenters. Coinbase identified the odd examples that arise with how the IRS identifies brokers with reporting requirements in its proposal:

- Providing access to a protocol

- Providing an automated market maker system

- Providing services to discover competitive buy and sell prices

- Providing non-custodial wallets that allow users to access trading platforms

- Providing services that allow access to the internet, including browsers and ISPs[7]

These are absurd broker use-cases and feel very much like spaghetti hurled against a wall; by all accounts, the IRS has undercooked its proposal. The IRS identifies digital asset middlemen and explicitly specifies the non-custodial wallet. A non-custodial wallet is software that mathematically creates addresses on a blockchain and allows a user to interact with those addresses by sending and receiving cryptocurrency. It is not necessarily written by a U.S. citizen or entity. It is not necessarily distributed by a centralized entity. It is programmatic mathematics—a software program—and would work seamlessly whether identity existed or not. If all of the wallet software suddenly required identify verification (this alone is an impossible hypothetical), a new one would simply emerge that did not require identity, and it would be distributed anonymously. We already know how to do that.[8] Does the IRS intend to issue a John Doe summons to the bitcoin developer group? Surely, it knows enough about blockchains to know that the developer group does not have insight into identities transacting on bitcoin’s blockchain (nor does anyone else for that matter).[9] It is not possible to know any identify other than self-disclosure or through cooperation from third-party U.S. based exchanges who respond to a John Doe summons from the IRS, such as Coinbase, Gemini, and Kraken (although the latter objected at first). These entities are centralized and want to do business in the U.S., so they comply with regulators and may share data with third-party aggregators like Chainalysis, Elliptic, CipherTrace, and others. Other service providers, such as Xapo, simply eliminated U.S. citizens from its user base. The IRS is attempting, in its maddeningly broad definition of brokers, to encapsulate all other entities, even non-entities, such as anonymous software. Coinbase provides its own reductio ad absurdum in the last bullet point, perhaps hoping to garner support from the larger lobby budgets of Internet Service Providers (ISPs), Microsoft, Google, and Apple.[10]

Right to Privacy Issues

These proposed regulations stem from the imaginary tax gap; the difference between an amount of taxes the IRS imagines it should receive and the amount it actually receives. Their misguided attempts hyper-focused on cryptocurrency illustrate their feeling that the thing they know very little about, but see indications all around, must be where the large value is concealed and that must warrant the rushed, misplaced scrutiny at great cost to all involved. Any financial expert in matrimonial litigation can attest to the unfortunate fact that one spouse often places a large value on the unknown and finds many indications where there may be but few. Spouses will expend more than the asset value chasing that unknown, and more recently they expect that large unknown value to be found within cryptocurrency. The IRS closely resembles the non-crypto spouse with this proposal, flailing in its misguided attempts to grab at an unknown value, however small and at whatever cost.

Unlike the non-crypto spouse in a divorce, the IRS has definitions at its disposal and decided that anyone who effects a transfer should be gathering data and reporting it, neighbors included. Coinbase cries out against this broadened definition, stating that the IRS, in using the word “effect” rather than “effectuate” gathers together all those who are tangentially, rather than directly involved in transactions. Coinbase argues that it is directly involved in transactions and should be reporting, although not to the extent the IRS proposes, but others, such as “facilitative services” where “a person knows or would be in the position to know the identity” of transactors should not be gathering data and reporting it. If you see your neighbor engaging in a crypto transaction, grab your camera, says the IRS, according to Coinbase.

Coinbase laments, “the reporting of digital assets used for payments is the equivalent of 24-hour surveillance of taxpayers … this requirement would be tantamount to mandatory reporting of the financial and spending habits of Americans across their entire lives”, and “once wallet addresses are linked to individuals, this leaves open the real possibility that a successful cyber-attack of either a government system or reporting broker could reveal a taxpayer’s entire on-chain transaction activity”. These are more fine words from the centralized entity that is itself a target of successful cyber-attacks, putting Americans’ identities and funds at risk (and in fact, failing to prevent their loss in crypto investment scams where Coinbase is well-positioned to assist using basic transaction analysis).[11] However ironic a messenger Coinbase makes, the implicated burden and the invasion of privacy here is unnerving.

One of the programmers who developed the ERC-721 standard (NFTs), William Entriken, also commented on the privacy issues put forth by the IRS explaining that not all transactions are or should be available to the government (after all, we do have a right to financial privacy around here … or at least we did); for instance, the law does not allow reporting an individual’s transactions related to certain types of purchases (guns, abortions, etc.) and reporting individual transactions would contrast with a right to privacy, legally.[12] That is a nice way for Entriken to say that what the IRS is asking for is a crime. To summarize the concerns, the proposal from the IRS is a fishing expedition highly likely to result in phishing expeditions.

Another method for transparency in blockchain transactions that would enable the IRS to identify appropriate reporters for any individual under audit is for exchanges to publicly disclose all of their hot wallet addresses; this is a very low-cost endeavor for exchanges and does not put any consumer’s identity or financial privacy at risk. The IRS woefully excludes both the hot wallet disclosure solution and the price reporting requirement solution.

Basis Without Basis

Different fact patterns support different basis calculations in the IRS proposal. When digital assets are purchased for cash, the basis of the digital assets purchased is the amount of cash paid plus any allocable digital asset transaction costs. If instead, a user buys crypto with some other property, the basis of digital assets acquired in exchange for property other than digital assets is the cost of the acquired digital assets plus any allocable digital asset transaction costs.

If the assets in the exchange differ materially, then only half the costs are claimed by the buyer and half claimed by the seller. This rule is preposterous when a decentralized exchange is considered; the fees are borne by the user and are allocable transaction costs. If USDC, a self-proclaimed stablecoin, is exchanged for some other non-stablecoin asset, can it be said that the two assets differ materially? If so, then calculating the FMV becomes an odd thing to do because, as a stablecoin, USDC self-proclaims that it is a cash equivalent. If that exchange occurs on Uniswap, will Uniswap report that to the IRS? Probably not because “they” are decentralized software, not people.

As the cost basis section goes on, it becomes painfully clear that these proposed regulations presuppose that all cryptocurrency transactions occur akin to a stock sale (regardless of what federal courts, district courts, and the SEC have already said), between U.S. citizens subject to tax reporting (i.e., defi simply does not exist; it does), using tokens that are traded in an active, liquid market (most are not traded that way), all programmers have access to the complete identities of all the users of each algorithm they have ever written (they do not), all things that provide access to transaction-enabling software have complete identities of all the users of that software and the capacity to report on every individual (see the first presupposition and they do not). For assets received in an exchange, the cost is the FMV as of the date and time of the exchange. If FMV cannot be determined with reasonable accuracy, FMV must be determined with a reference to the property transferred and the IRS considers this analogous to the rule requiring the FMV of property received, when non-crypto is exchanged for property. This is only possible if there is a standard for FMV for that asset class.

The IRS redefines “FMV” as “market value” identifying that the FMV of a cryptocurrency is the price at which it trades on an exchange; that is not what FMV is and tens of thousands of cryptocurrency assets are not traded on an exchange, so even if FMV were calculated in that way, it would not be possible for most altcoins. The IRS says, “Never mind all that. Do it anyway.”

To redefine “FMV” as simply “market value” with such a heavy hand, thereby ignoring all contracts and ignoring the impossibility of that calculation for most cryptocurrencies, seems unfair. In fact, it places a very large cost burden on taxpayers who no longer have access to market prices, which are not published by any entity in any consistent or standardized manner. The only way to effect or effectuate FMV calculations and market value calculations is to require exchanges to release that information to the public in a standardized and accessible way (such that it can be readily scraped and consolidated). Historical pricing is not readily available except in very small subsets; anything more, such as historical pricing data for a delisted asset, requires a cost outlay of tens of thousands of dollars (paid to price aggregators, who must be falling over themselves with joy with this proposal).

As it relates to litigation, the IRS provides the mildly litigious with a basis on which to run rampant. In its cost basis proposals, the IRS absurdly recommends a 50/50 cost sharing between parties exchanging assets that have a material difference in kind or in extent. In a transaction with good and fair consideration, how can such a transfer be off-balance? It is the transaction itself that equalizes both sides of the transaction; this proposal is not only absurd, it is also unenforceable because it presumes that both sides of a transaction are identifiable, are subject to U.S. tax reporting and payment, and are physical entities that can be pursued for nonpayment. None of these presumptions are true. For instance, a smart contract, which is code that runs automatically on a blockchain, has no identifiable author, and has no centralized controlling entity, must somehow be held responsible for half the transaction costs in these cases.

There is another issue here as well: a material difference in kind or in extent is left to the reader’s imagination. The concept itself appears to undermine contract law and the basic premise of a transfer itself (both sides being equalized). No further description of a material difference in kind or in extent is provided by the IRS.

Conclusion

Despite all the issues in the 300 pages of broker definitions, calculation scenarios, and infrastructure misunderstandings, practitioners in valuation and litigation need to prepare for the normalization of cryptocurrency within their practice. Part of that preparation is keeping up to date with new information and pending regulations, and another part is learning new applications for their skills such as determining the FMV of cryptocurrency assets that are not traded in an active, liquid market. The most prevalent of these is a non-fungible token (NFT). Determining the Fair Market Value for an NFT: A Practice Guide for Practitioners is coming next.

Disclaimer: This article does not substitute for legal, tax, or financial advice and is intended for general informational purposes only. This article does not constitute an expert opinion and should not be construed as such.

[1] Coinbase Letter, Re: Gross Proceeds and Basis Reporting by Brokers for Digital Asset Transactions, Oct. 12, 2023.

[2] See Bitcoin white paper, archived at https://bitcoin.org/en/bitcoin-paper, Oct. 31, 2008, in fact, the authors of this paper are hyperaware of the retributions exacted for undermining centralized systems and chose to stay anonymous; See also, Security without Identification: Transaction Systems to Make Big Brother Obsolete, David Chaum, Oct. 1, 1985, Communications of the ACM, Volume 28, Issue 10pp 1030–1044https://doi.org/10.1145/4372.5.

[3] With the exception of cooperation from third-parties, such as exchanges, data aggregators, and users themselves.

[4] Microsoft Bing browser, Google’s browser, and Apples’ Safari browser each allow for plugins that provide a user with the ability to access wallet services, thus indirectly facilitating transactions, and thereby may be brokers.

[5] https://quickreadbuzz.com/2023/07/26/financial-forensics-dorothy-haraminac-the-latest-greatest-internet-scheme/.

[6] See the Right to Financial Privacy Act and the Financial Services Monetization Act; at the mention of a list of all the people using crypto to purchase guns, the NRA should have been up in arms but, alas, they were not on the call.

[7] Gross Proceeds and Basis Reporting by Brokers and Determination of Amount Realized and Basis for Digital Asset Transactions, Internal Revenue Service, Aug. 28, 2023, https://www.regulations.gov/document/IRS-2023-0041-0001.

[8] Where precise regulatory specifications related to licensing and registration requirements exist.

[9] NTUF’s Comments on IRS Cryptocurrency Regulations, National Taxpayers Union Foundation, Lindsey Carpenter, Nov. 14, 2023, https://www.ntu.org/foundation/detail/ntufs-comments-on-irs-cryptocurrency-regulations.

[10] Gross Proceeds and Basis Reporting by Brokers and Determination of Amount Realized and Basis for Digital Asset Transactions, Internal Revenue Service, Aug. 28, 2023, https://www.regulations.gov/document/IRS-2023-0041-0001

[11] FIFO: First In First Out and LIFO: Last In First Out are inventory accounting methods.

[12] Description of behavior is added for levity and should not be taken literally.

Dorothy Haraminac, MBA, MAFF, CFE, PI, provides financial forensics, digital forensics, and blockchain forensics under YBR Consulting Services, LLC, and teaches software engineering and digital forensics at Houston Christian University. Ms. Haraminac is one of the first court-qualified testifying experts on cryptocurrency tracing in the United States and provides pro bono assistance to victims of cryptocurrency investment scams to gather and summarize evidence needed to report to law enforcement, regulators, and other parties. If you or someone you know has been victimized in an investment scam, report it to local, state, and federal law enforcement as well as federal agencies such as the FTC, the FCC, and the IRS.

Ms. Haraminac can be contacted at (346) 400-6554 or by e-mail to admin@ybr.solutions.