Essential Guide to Gift Tax and Estate Planning

Consider the SLAT and GRAT in Gift Planning

Understanding gift tax regulations is crucial for individuals and their advisors because it impacts estate planning strategies and can significantly affect the overall tax liability. Properly utilizing exemptions and understanding the rules surrounding gift taxation can help individuals minimize their tax burden and ensure a smooth transfer of assets to their intended beneficiaries. This article discusses the availability of the SLAT and GRAT gifting techniques.

Understanding gift tax regulations is crucial for individuals and their advisors because it impacts estate planning strategies and can significantly affect the overall tax liability. Properly utilizing exemptions and understanding the rules surrounding gift taxation can help individuals minimize their tax burden and ensure a smooth transfer of assets to their intended beneficiaries. This article discusses the availability of the SLAT and GRAT gifting techniques.

The concept of gift and estate taxes dates as far back as 700 B.C., and research suggests that Egypt implemented a 10% tax on property transfers upon death. Similarly, in the first century A.D., Augustus Caesar levied a tax on inheritances and bequests, excluding only immediate family members.[1] During the Middle Ages, transfer taxes emerged due to the belief that all assets belonged to the sovereign or the state. In the United States, the taxation of assets upon death can be traced back to the Stamp Act of 1797. Although the initial Stamp Act, notably targeting tea, contributed to the Revolutionary War, its subsequent implementation had a less pronounced effect. Revenues raised from requiring a federal stamp on probate wills were used to settle debts incurred during the undeclared naval conflict with France in 1794. Congress repealed the Stamp Act in 1802.[2] In the United States, the taxation of decedents’ estates has been in effect since 1916. The gift tax was initially introduced in 1924, abolished in 1926, and then reinstated in 1932 with the aim to curb estate tax avoidance by preventing donors from transferring their wealth (assets) before death to avoid estate taxes.

The IRS defines the gift tax as a “tax on the transfer of property by one individual to another while receiving nothing, or less than full value, in return. The tax applies whether or not the donor intends the transfer to be a gift. The gift tax applies to the transfer by gift of any type of property. An individual makes a gift if they give property (including money) or the use of or income from property without expecting to receive something of at least equal value in return. If an individual sells something at less than its full value or if they make an interest-free or reduced-interest loan, they may be making a gift. [3]”

The estate tax pertains to a tax on an individual’s right to transfer their property upon death. This encompasses all possessions and assets an individual owns at the time of their passing, such as cash, jewelry, business holdings, real estate, investments, annuities, and more, collectively constituting their “Gross Estate.” It is essential to note that all assets must be documented at their fair market value, which is determined as per Section 20.2031-1(b) of the Estate Tax Regulations and Section 25.2512-1 of the Gift Tax Regulations. Fair market value is defined as:

“[T]he price at which property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller, neither being under any compulsion to buy or sell and both having reasonable knowledge of the relevant facts.[4]”

Once the Gross Estate is accounted for, certain deductions are allowable to arrive at “Taxable Estate.” According to the IRS, “these deductions may include mortgages and other debts, estate administration expenses, property that passes to surviving spouses and qualified charities. The value of some operating business interests or farms may be reduced for estates that qualify.[5]”

The total value of gifts made during the individual’s lifetime that are subject to gift tax (beginning from the year 1977) is included in the calculation of the Taxable Estate. From this Taxable Estate value, the estate tax owed is calculated based on the prevailing estate tax rates. Should the aggregate value of the deceased individual’s Gross Estate (factoring in taxable gifts and specific gift tax exemptions) surpass the threshold established by tax regulations for the year of their passing, an estate tax return is mandatory with the IRS. Presented next is a table illustrating the filing thresholds for the year of death (for an individual).

|

Year of Death |

If Amount Described Above Exceeds: |

|

2017 |

$5,490,000 |

|

2018 |

$11,180,000 |

|

2019 |

$11,400,000 |

|

2020 |

$11,580,000 |

|

2021 |

$11,700,000 |

|

2022 |

$12,060,000 |

|

2023 |

$12,920,000 |

|

2024 |

$13,610,000 |

Hence, when an individual opts to give a monetary sum, a vehicle, or a property/asset, it is not without implications, and the IRS requires disclosure if the value of the gift exceeds $17,000 in 2023 (or $34,000 if jointly gifted with a spouse). In 2024, these thresholds increase to $18,000 individually or $36,000 with a spouse. An essential facet of gift taxation is the lifetime gift tax exemption. Should the gift surpass the yearly limit, the surplus is offset against the lifetime gift tax exemption. Presently, the exemption stands at $12.92 million per donor in 2023, applicable to both gift and estate taxes. However, this exemption is temporary and only applies through 2025. Absent Congressional alterations, post-2025, the exemption is slated to revert to $5.49 million, adjusted for inflation. For individuals and families with assets surpassing $12.92 million, various strategies are available to capitalize on the current gift tax exemption before its sunset in 2025, which potentially subjects a substantial portion of assets to be taxed at a 40% tax rate.

Qualified attorneys can assist in identifying the most suitable approach for wealth transfer and navigating specific family circumstances and asset allocations. For example, among the tools available, two noteworthy options include the Spousal Lifetime Access Trust (SLAT) and the Grantor Retained Annuity Trust (GRAT).

- A SLAT is an irrevocable trust created by one spouse for the benefit of the other spouse and possibly other family members, such as children or grandchildren. The spouse who creates the trust (the grantor) transfers assets into the trust, removing them from their taxable estate. The trust allows the non-grantor spouse to access the trust assets during their lifetime, providing financial security. Upon the death of the non-grantor spouse, any remaining assets in the trust pass to the designated beneficiaries, such as children, free from estate taxes.

- A GRAT is an irrevocable trust established by a grantor to transfer assets to beneficiaries while retaining an annuity payment for a specified period. The grantor transfers assets into the trust and retains the right to receive annual annuity payments from the trust for a predetermined period. At the end of the trust term, any remaining assets in the trust pass to the designated beneficiaries, typically free from gift or estate taxes. If the assets appreciate at a rate higher than the IRS’s assumed rate (the Section 7520 rate), the excess appreciation passes to the beneficiaries tax-free.

Business valuation plays a crucial role in determining the value of assets transferred into these trusts, and effective estate tax planning ensures that assets are transferred in a tax-efficient manner to achieve the desired financial objectives.

Business valuations intended for gift and estate tax purposes must conform to the relevant guidelines outlined in the Internal Revenue Code (“Code”) and Treasury regulations. Within the domain of estate and gift taxation, the prescribed benchmark for valuation is fair market value, as previously defined. Business valuations performed for federal gift and estate tax purposes must consider and follow the factors listed in Internal Revenue Service Revenue Ruling 59-60. This revenue ruling states that the following eight factors are fundamental and should be considered in each case:

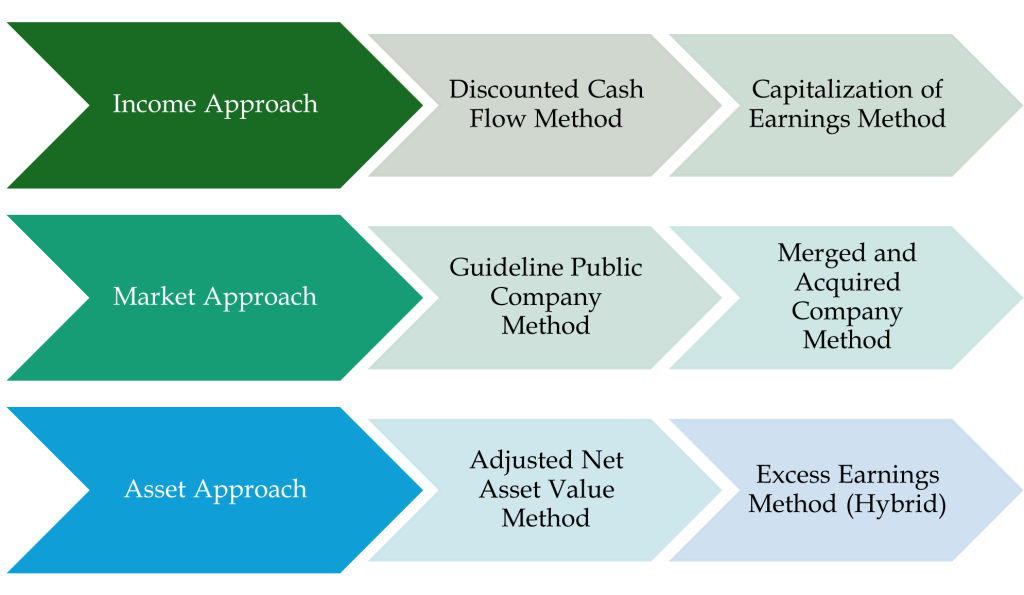

Three traditional valuation approaches can be used to establish the fair market value of a business: (i) income approach, (ii) market approach, and (iii) net asset (or cost) approach. Within these three basic approaches, several methods may be used to estimate value. An overview of these approaches and their corresponding methodologies follows.

Income Approach

The income approach is a methodology utilized to ascertain the value of an investment, such as a business, ownership interest, security, or intangible asset. It employs one or more techniques to translate the anticipated future economic benefit associated with the investment into a singular “present value” figure. According to IRS Revenue Ruling 59-60, valuation analysts are advised to factor in the business’s earning potential when determining fair market value. This approach relies on the following two techniques: capitalization and discounting. The present value of future benefits is established by applying a discount rate, which accounts for the time value of money, pertinent investment attributes, the perceived level of risk in the market, and the subject investment.

- The capitalization of earnings method is an income approach that determines the value of a business by assessing future projected earnings generated by the company. These anticipated earnings are then capitalized using an appropriate capitalization rate. This method assumes that all tangible and intangible assets are integral components of the business and does not endeavor to differentiate between the values of each. It is commonly employed to appraise operational businesses or entities with low capital intensity, such as service or professional organizations. Moreover, if historical earnings have exhibited stability and are anticipated to remain constant or grow at a foreseeable rate, the capitalization of earnings method is typically employed to derive an indication of value.

- The discounted cash flow method, under the income approach, operates on the principle that the assessed worth of a business equals the present value of its projected future earnings, along with the present value of the company’s terminal value. This is a multi-period valuation technique. This methodology proves applicable in scenarios where future earnings are anticipated to undergo substantial year-to-year fluctuations and where such variations are reasonably foreseeable.

Market Approach

The market approach is a valuation methodology grounded on the principle of substitution. Its fundamental premise involves examining companies within the same industry as the subject company to offer valuation benchmarks. Comparisons are drawn between the subject company and similar companies whose stocks are actively traded on the exchange or over the counter (e.g., NYSE, NASDAQ, etc.). Valuation multiples for such companies are computed and scrutinized. A valuation multiple is derived by dividing the price of the guideline company’s stock as of the valuation date by a relevant economic variable observed or calculated from the guideline company’s financial statements.

Furthermore, it is crucial to consider valuation multiples indicated in comparable merger and acquisition transactions. Transactional data can furnish robust indications of value in company appraisals when employed diligently and meticulously. Additionally, it is imperative to consider any previous transactions involving the subject company’s capital stock.

- The guideline public company method, a market-driven approach, operates under the premise that pricing multiples (i.e., the relationship between the price of publicly traded stocks and various other factors such as earnings, sales, book value, etc.) of publicly traded companies can serve as an indicator of value for closely held appraisal subjects. By making necessary adjustments, these pricing multiples can be applied to similar factors of the appraisal subject to determine an estimated value for the subject company. For instance, a price-to-earnings multiple would be applied to the company’s earnings, while a price-to-EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) multiple would be applied to the company’s EBITDA, and so forth.

- The guideline merged and acquired (transaction) company method is a market-based approach. This appraisal methodology is based on the premise that pricing multiples can be used as an indicator of value to be applied in valuing a closely held appraisal subject. GMAC entails estimating a company’s value by referencing the market values of comparable companies that have undergone mergers or acquisitions previously. From these transactions, multiples are derived, which can then be applied to the corresponding financial metrics of the specific business undergoing appraisal.

Asset Approach

The asset-based approach, often referred to as the cost approach, determines the fair market value by adjusting the asset and liability balances of the company to their fair market value equivalents. This method relies on identifying, valuing, and totaling the tangible and intangible assets of the company.

- The adjusted net asset value method represents an asset (cost) approach to valuation, whereby the business’s worth is determined as the difference between the fair market value of its assets and liabilities. This strategy proves effective for assessing the value of a non-operating enterprise, such as a real estate holding company, an investment holding company, an asset-heavy business, or a business experiencing ongoing losses or slated for liquidation.

- The excess earnings method (hybrid method) is a valuation approach that integrates both income and asset considerations, wherein the adjusted net tangible and intangible assets of the business entity are assessed separately. These constituent assets are subsequently amalgamated to ascertain the total fair market value of the business. When relying on the excess earnings method, intangible assets are appraised by capitalizing the surplus earnings of the business, which denotes the earnings exceeding those necessary to yield a reasonable rate of return on the adjusted net tangible assets of the business. It is worth noting that the IRS and the Tax Court view this method as a last resort, to be employed only when implementing other methodologies would not be appropriate.

For a considerable time, courts have consistently supported a widely acknowledged principle, often echoed in professional assessments: that the worth of closely held business interests typically falls short of the value of a comparable publicly traded company where an investor can convert his or her investment to cash within a few business days. For a closely held business, there is the challenge of swiftly converting the property into cash at a minimal cost, which is referred to as lack of marketability. Furthermore, if the interest being valued is less than a majority or control stake and cannot influence managerial decisions and other facets of the entity, this is referred to as a lack of control. Thus, in valuing minority, non-marketable interest, it may be appropriate to consider and apply a discount for lack of control (DLOC) and/or discount for lack of marketability (DLOM).

When assessing the value of a non-controlling (minority) ownership stake in a company, it is important to differentiate between the value of such a non-controlling interest, which lacks the ability to exert control over the business, and the value of an actual controlling interest. Essentially, the collective value of partial interests may not equate to the value of the entity as a whole. A complete business entity holds a distinct value due to its conveyance of various rights. Holders of non-controlling interests face limitations and are at a relative disadvantage in influencing management decisions due to their lack of absolute voting power. Since management possesses control over fund allocation, it can significantly influence the profitability and overall operations of the company.

Numerous studies have explored the premiums paid in the acquisition of public companies. One notable source is the Mergerstat Control Premium Study, conducted by Mergerstat, a subsidiary of BVR. This study furnishes data on control premiums across diverse industries and market conditions (updated annually) covering a substantial portion of the M&A market in the United States and abroad. Financial professionals, including investment bankers, corporate finance specialists, and valuation experts, widely utilize data from the Mergerstat Control Premium Study as a reference point for control premium analysis in M&A transactions and to calculate the corresponding DLOC. The DLOC represents the reduction in value associated with owning a minority interest rather than a controlling interest in a company. A DLOC is calculated as the inverse of the selected control premium (as provided by Mergerstat transactions) as follows: Discount for Lack of Control = 1 – (1 / (1 + Control Premium)).

Marketability is defined in the International Glossary of Business Valuation Terms as “the ability to convert property into cash at minimal cost.” A DLOM is described as “an amount or percentage subtracted from the value of an ownership interest to account for the relative absence of marketability.” Consequently, a DLOM is typically applicable when there is no readily available market for the interest under consideration, which is often the case for most small businesses. It is relatively straightforward, quick, and inexpensive to convert publicly traded securities into cash at the owner’s discretion. Generally, publicly traded common stocks can be sold immediately, with cash settlement occurring within two to three business days. IRS Revenue Ruling 77-287 acknowledges the lack of marketability for privately held business interests:

“Whether the shares are privately held or publicly traded affects the worth of the shares to the holder. Securities traded on a public market generally are worth more to investors than those that are not traded on a public market.”

A closely held entity lacks the marketability of publicly traded entities. Therefore, an ownership interest in a business is more valuable if it is easily marketable or, conversely, less valuable if it is not. When a prospective seller seeks a willing buyer, they face significant risks due to fluctuating market conditions, the time required to finalize the transaction, or changes in the financial needs of the subject company.

The quantification of the DLOM has been the focus of numerous studies, including those analyzing restricted shares of publicly traded company stock and closely held company stock before an initial public offering (IPO). These studies compare the same company’s shares in a marketable state to a non-marketable state. Articles and studies discussing DLOM (based on corporate stock) indicate that the discount’s magnitude depends on various factors, including dividend or distribution size, sale restrictions, future IPO or sale prospects, the existence of buy-back agreements or put options, earnings level, volatility, potential buyer pool, issuer size and financial strength, and minority interest holders’ access to information and reliability.

The courts and the financial reporting sector have recently leaned towards quantifying DLOM. A synthetic put option model is a method used to estimate the lack of marketability discount in valuing privately held companies or other illiquid assets. DLOM reflects the asset’s reduced value due to the absence of a ready market and the associated challenges and costs of selling it.

A put option grants the holder the right, but not the obligation, to sell an underlying asset at a specified price (strike price) within a predetermined time frame. The synthetic put option model operates on the notion that an investor holding an illiquid asset is in a similar position to one holding a put option on a publicly traded security. Just as a put option enables the holder to sell the underlying security at a set price, the investor with an illiquid asset has the right to sell it if a market were available.

According to David Chaffe: “If one holds restricted or non-marketable stock and purchases an option to sell those shares at a market price, the holder has, in effect, purchased marketability for those shares. The price of this put is the discount for lack of marketability.”

In a synthetic put option scenario, the illiquid asset being valued serves as the underlying asset, and the strike price represents the estimated market value of the asset. The model’s outcomes can be used to adjust the estimated market value of the asset to reflect its lack of marketability. However, it is important to note that DLOM is a subjective estimate and may vary based on the assumptions and inputs used in the calculation. Like all valuation methods, the synthetic put option model should be utilized as a tool to gain insight and make informed decisions rather than as a prediction of the exact DLOM.

In the words of Henry David Thoreau, “Wealth is the ability to fully experience life.” This sentiment underscores the importance of understanding the intricacies of gift taxation in the U.S., including the lifetime gift tax exemption. By grasping these concepts, individuals and their trusted advisors can confidently navigate estate planning, optimizing their wealth and financial future while embracing life experiences and opportunities to the fullest and optimum extent.

[1] The Estate Tax: Ninety Years and Counting, by Darien B. Jacobson, Brian G. Raub, and Barry W. Johnson, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/ninetyestate.pdf.

[2] The Heritage Foundation: Estate Taxes – A historical perspective (2004), https://www.heritage.org/taxes/report/estate-taxes-historical-perspective.

[3] IRS – Gift Tax: https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/gift-tax.

[4] Internal Revenue Service, Treasury, § 20.2031–1, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2013-title26-vol14/pdf/CFR-2013-title26-vol14-part20-subjectgroup-id210.pdf.

[5] IRS – Estate Tax: https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/estate-tax.

Nataliya Kalava, CVA, ABV, MAFF, is an expert in the fields of business valuation and finance, with about 15 years of experience. She has led and contributed to numerous valuations for diverse purposes, including gift and estate tax planning, management planning, M&A transactions, SBA valuations, financial reporting, and litigation support. Ms. Kalava’s passion lies in helping business owners navigate ownership transitions, guiding them through challenges, and uncovering opportunities for growth. Her expertise is honed through a rich career journey, having worked with renowned organizations such as Equinix Inc., Humana Inc., BDO LLP, Sigma Valuation Consulting Inc., and PwC. Ms. Kalava’s dedication to her profession extends to education and community engagement. She has been an Adjunct Finance faculty member at the University of Tampa, imparting her knowledge to undergraduate students on corporate finance and investment. Furthermore, she organizes Continuing Legal Education (CLE) courses on business valuation topics accredited by the Florida Bar.

Ms. Kalava can be contacted at (813) 999-1144 or by e-mail to nkalava@one10firm.com.