You Want the Valuation Experts to Reconcile

Are You Prepared for the Outcome?

What can parties in a litigation case do when the experts come to differing opinions of value? The authors share ways that parties and counsel can reconcile the differences or at least reduce the value gap.

It sounds great—if the valuation experts can resolve their differences, a trial might be avoided, saving time and money. This strategy is not without peril, and clients may even find themselves unexpectedly bound by an agreement or terms they did not expect. This article covers what ensues when opposing legal counsels agree for the experts to meet, including how to manage the expectations and how to structure those meetings. Communicating objectives to the expert and understanding the process will improve the effectiveness of discussion between experts and increase the likelihood of success.

To Meet or Not to Meet

Counsels’ decision to have experts talk to each other deserves careful consideration. Comparing the estimate of professional fees with the cost of trial helps to serve as an initial test. If the difference between the two opinions of value is less than the cost to litigate, it could make financial sense to have the experts talk.

The following factors should be weighed in determining whether to have the experts attempt to resolve their financial differences:

- Theory Differences. Isolating the key differences may offer an alternative to an expert meeting. For example, if the main difference between the two expert reports is the expected gross profit margin, counsel can assess whether to negotiate the issue independently or take it to trial.

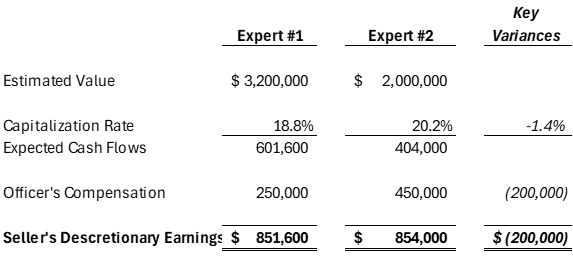

The simplified example below shows how a $1.2 million difference between two value opinions can largely be explained by the variance in officer’s compensation. Working backwards from the value estimates of $3.2 million (Expert #1) and $2.0 million (Expert #2) reveals that both analysts started with a seller’s discretionary earnings (SDE) figure of approximately $850,000.

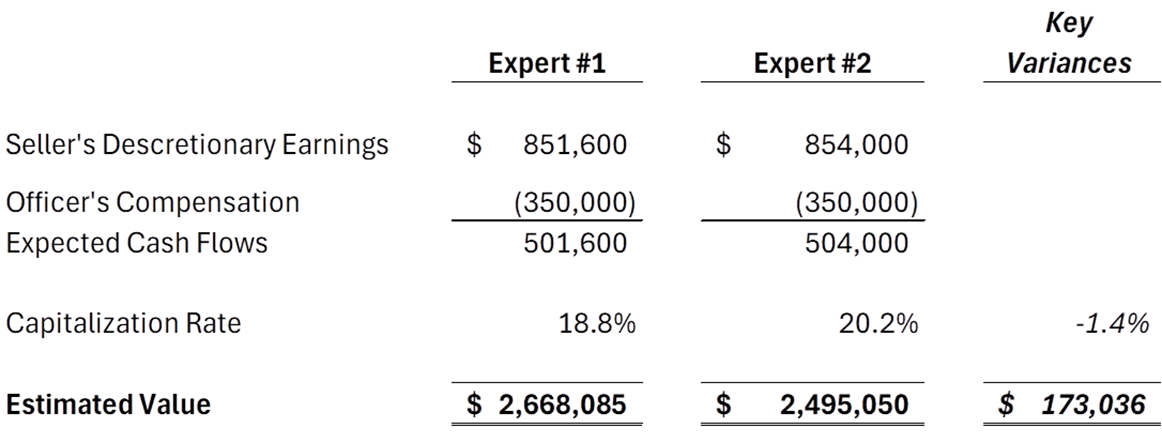

Isolating the officer’s compensation helps reconcile the difference in value, making the cost of capital difference (1.4%) a secondary factor. Substituting $350,000 for the officer’s compensation in both scenarios below reconcile the variance.

As shown above, reducing the theory differences to one or two items might be sufficient to resolve the case. While the difference in the cost of capital remains, the resulting values are nearly identical so the officer’s compensation can be negotiated. Be aware that compensation may comprise of multiple adjustments such as vehicle allowance, health insurance, retirement contributions, and other discretionary spending.

- Percentage Difference. While the dollar variance between the expert opinions may be significant, reframing into percentage differences may provide an opportunity to settle the case without an expert meeting. Expert opinions within 10% of each other may be considered within the margin of error.[1] In the previous example, the 60% difference in values may justify an expert meeting had there been additional differences.

- Discovery Status. If so, management may have the data needed to bridge the gap between the two opinions. For example, journal entries posted to cost of goods sold and paid for with cash may be interpreted by one expert as overcoming supply chain shortages whereas the other expert sees disguised distributions. Two equally qualified analysts may reasonably differ in their interpretation of how the expected cash flows and risks translate to business value.

Sharing specific information such as receipts, e-mail communications, or other supporting documents may provide the missing link in the negotiation process. As valuation is, in essence, a prophecy into the future,[2] providing support for anticipated operational changes, capital investment, etc., could clarify the issue so differences can be negotiated.

- Case Strategy. The experts may reveal the weakness in their counterpart’s methodology, allowing the other analyst to prepare for a future cross examination. Depending on the perceived strength of the expert report, counsel may not want to tip off the opposing side prior to trial.

- Available Alternatives. The facts and circumstances will dictate whether formal alternative dispute resolution (ADR) would be more appropriate than informal negotiations. Mediation and arbitrations utilize third party neutrals, which add a layer of objectivity to the process. Valuation analysts receive specialized training in their field, yet the valuation credential curriculum does not include negotiation training. Using professionals trained in effective negotiation methodologies will help keep the process on track and mitigate power differentials.

Other alternatives include hiring a “tiebreaker” valuator, depositions, interrogatories, or selling the business on the open market. Transferring the ownership interest to a third party will provide the true fair market value of the business.

The parties should know their best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA)[3] prior to engaging experts to potentially resolve their differences. The experts may initially prepare worksheets reconciling the values, run various scenarios, and prepare charts or other visual aids to identify material differences. A meeting might not be necessary if counsel is able to reconcile and weigh the importance of the key points or hire a separate rebuttal expert to help prepare for trial. The better the alternatives, the easier it is to walk away from this process.

Other aspects of the case may be more important to the parties than the business value. In a divorce, custody of the kids may be the primary objective, and the business valuation can be used as leverage to that end.

Expectations for the Meeting

Once the decision is made to have the valuation experts communicate, counsel should provide clarity regarding their objectives for the meeting. This includes providing consent to disclose confidential information as required by professional standards.[4] Clients, especially non-financial parties, may be unable to express their expectations without advance preparation, so allow time to conceptualize the range of acceptability. The following are common expectations:

- Experts as Agents. The most important consideration in preparing for the expert meeting is to understand whether the outcome will be binding. It is often presumed that the litigants can veto any expert settlement. That may not be the case if the judge determines the experts were serving as fiduciaries or agents. Most experts are not attorneys and are unable to differentiate a compromised agreement from a binding contract. Judges have concluded that expert agreements are binding, so minimize confusion by circulating a stipulated agreement outlining the ground rules and immediately communicating any disputes after the expert meeting.

- Split the Difference. Experts reaching an agreement that is exactly 50% of the differences is uncommon and splitting the difference is less likely in today’s courts. For example, in Massachusetts, the Supreme Judicial Court found that valuations will be based on evidence or reasonable inferences from it;[5] this means picking the more credible expert or determining their own conclusions. Counsel should be prepared so that any expert resolution may result in the other side walking away with the lion’s share of the difference.

- Resolution Models. Expert conversations may benefit from a recognized standard for conflict resolution. The facts, issues, feelings, and interests (FIFI) simplified model used by the IRS for mediation purposes[6] may shape the foundation of productive interactions through understanding the FIFI of both sides. All opinions of value contain bias[7] based on the analyst’s subjective judgments, predetermined value estimates, or other factors. Experts who focus on the supporting data with a mind open to contradictory information are more likely to compromise than those who want to prove they are “right.”

- Conflicting Valuation Dates. When the experts have different valuation dates, the reconciliation process is more complex. In these situations, counsel should set guidelines for the experts to incorporate or exclude subsequent events. For example, directing the experts to use certain assumptions (such as the latest debt balance) may provide a workable starting point. If there is too much complexity, consider extending discovery to revise the reports or seek other alternatives.

- Other Expectations. Coordinating schedules and location may make the arrangement impractical if the trial is imminent. Memorializing consent for the experts to talk may prevent problems with information sharing.

Negotiation is about finding a solution to your counterpart’s problem that makes you better off than you would have been had you not negotiated.[8] Setting expectations early in the process will help avoid disappointment later.

Structure of the Meeting

Once clients and experts share the expectations about possible outcomes from the expert meeting, the next stage of the process is determining the format. Aspects of this process include:

- Meeting Forum. In the post-pandemic world, it is easy to set up virtual meetings without the added costs of travel. However, in-person settings are recommended for high stakes discussions that have the potential to resolve the case. The importance of observing nonverbal communication and creating an atmosphere conducive to a productive conversation should not be sacrificed for the convenience of a virtual meeting. Valuation practitioners often have prior relationships and the meeting may be more productive over a meal or common interest.

- Who Else is Present. If the experts are experienced and have a history of collaborative successes, then an “unsupervised” forum might be acceptable. However, if one of the experts is early in their career, has an aggressive style, or has prickly personality quirks, then a third party “umpire” might be appropriate. Having a third person in the room may help keep focus on the important issues, build momentum of consensus, and avoid getting sidetracked with technical showboating such as how the potential repeal of IRC Section 199A affects the tax rate. Counsel should ask about the relationship between the experts before setting up the meeting.

Counsel and/or the parties’ presence may create the unintended consequence of pressuring the experts to put on a show for the audience, especially if the attendees participate in the process. This may morph into a dry run of the trial, rather than a productive, results-focused event.

- Meeting Length. Negotiations take time and may require more than one session. Instead of blocking off half the day, two separate meetings scheduled one week apart will allow experts time to research issues, run scenarios, and obtain approval from clients. Rushing the process may result in poor decisions and disappointing results.

- Follow-up. Counsel should establish the framework for what happens after the meeting. When experts meet in the morning, there may be time for an afternoon discussion with counsel, the expert, and client to relay the progress and discuss the next steps. A long gap between the expert meeting and communication with counsel creates memory lapses and divergent perspectives.

Counsel will also need to assess the enforceability of any expert agreement. For example, in Donna S. v. Travis S., the Supreme Court of West Virginia determined the mediated settlement agreement (MSA) was unenforceable because there was no “meeting of the minds”.[9]

Conclusion

Valuation experts reconciling their financial differences can be a valuable option in counsel’s case strategy. Everyone should have a clear understanding of the expert’s negotiation authority before the experts meet. Creating an acceptable range of values will help establish boundaries not to be crossed just to settle the case.

Saving time and professional fees is a consideration but should not come at the expense of an adverse outcome. Using the expert reconciliation process wisely may avoid both trial and unacceptable, yet binding “deals”, and produce a mutually acceptable value.

[1] See King, Alfred, Fair Value for Financial Reporting, John Wiley & Sons, 2006, Page 45: “Valuations, no matter how carefully prepared, and no matter how clear and supportable the assumptions, are never going to be accurate to much better than +/- 10%.”

[2] IRS Revenue Ruling 59-60; 1959-1 C.B. 237, §3.03.

[3] Fisher, R., Ury, W., and Patton, B., Getting to Yes, 2nd ed., Penguin Putnam, 2006.

[4] See NACVA Professional Standards General and Ethical Standards §II(G): Confidentiality, Revised December 19, 2023. “Unless required to do so by competent legal authority, a member/credentialed designee shall not disclose any confidential client information to a third party without first obtaining the express consent of the client.”

[5] Demoulas v. Demoulas Super Markets, Inc., 424 Mass. 501, 677 N.E.2d 159 (Mass. 1997).

[6] Gregory, Michael, Business Valuations and the IRS, Birch Grove Publishing, 2018, Page 239. See also the Eight-point Negotiation Process on page 270.

[7] See study conducted by Broekema, Marc et. al., Are Business Valuators Biased? A Psychological Perspective on the Causes of Valuation Disputes, Journal of Behavioral Finance, 2022, Vol. 23, No. 1, 23–42.

[8] Neale, Margaret, Five Steps to Better Negotiating, Insights by Stanford Business, July 16, 2015. See also Ms. Neale’s Stanford Executive Briefing – Negotiation: Myths, Misperceptions and Damned Lies: “Negotiation is where two or more parties decide what each will give and take in the context of their relationship and through a process of mutual influence determine a course of action.”

[9] Donna S. v. Travis S., 246 W.Va. 634, 874 S.E.2d 746 (2022).

Robert W. Carter, MS, CPA, CFF, ABV, CVA, CFE, CEPA, is a managing member of Paradigm Forensics, LLC, a Maryland-based valuation advisor and expert witness firm. He is one of the founders of Paradigm Forensics, LLC. During his many years of experience, he has employed his technical skills for creative problem solving in business valuation consulting, forensic accounting, fraud investigations and disputes. Furthermore, Mr. Carter has provided expert witness services in federal and state courts. He is an adjunct faculty member teaching graduate courses at universities in the Baltimore Metropolitan area and is also a faculty member for the NACVA where he teaches the CVA credentialing course.

Mr. Carter can be contacted at (410) 609-4740 ext. 102 or by e-mail to rcarter@paradigmforensics.com.

Mr. Pierce, CPA, CVA, CFM, MAFF, has over 30 years of experience and serves as a financial expert in various accounting and finance-related disciplines. He is a managing director and leads Paradigm Forensics’ Anchorage and Boston offices, and works with clients on disputes, transactions, fraud, damages, family law, criminal, and estate planning engagements. He is a lead instructor for NACVA’s Master Analyst in Financial Forensics certification program and other courses including the Forensic Accounting Academy and the Commercial Damages and Lost Profits Workshop. He is a regular speaker at legal and professional organizations. He is an active member of the Massachusetts Society of CPAs (Business Valuation Committee) and the Boston Chapter of the Institute of Management Accountants (Vice President – Education).

Mr. Pierce can be contacted at (410) 609-4740 or by e-mail to jpierce@paradigmforensics.com.