Net Working Capital

A Key Component Used in Business Valuation

For valuation purposes, net working capital involves a more comprehensive analysis than the straightforward traditional accounting definition of current assets minus current liabilities. This article examines the concept of net working capital and highlights its significance in business valuation.

Net working capital represents a vital aspect of business valuation, as it influences a company’s enterprise value through projected cash flows, as well as its equity value based on excess or deficient net working capital at the valuation date. For valuation purposes, net working capital involves a more comprehensive analysis than the straightforward traditional accounting definition of current assets minus current liabilities. This article examines the concept of net working capital and highlights its significance in business valuation.

What is Enterprise Value?

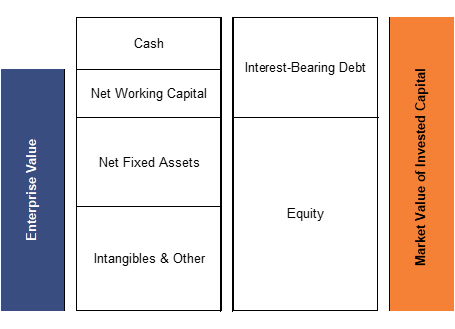

We begin our discussion of net working capital by defining the difference between market value of invested capital and enterprise value. As shown above, investors provide debt and equity capital (the right side), which the company then allocates to a portfolio of assets (the left side). The enterprise value of the business represents the “engine” that generates operating cash flow (of which EBITDA is often considered a proxy). Since cash balances do not generate EBITDA, cash and other short-term investments are excluded from enterprise value.

Working Capital vs. Net Working Capital?

Working capital is generally defined as current assets less current liabilities. In valuation, however, it excludes cash, non-operating assets, debt, and debt-like liabilities, focusing instead on accounts receivable, inventory, prepaid expenses, less accounts payable and accrued expenses. These exclusions align with the enterprise value concept, which is calculated on a cash-free and debt-free basis. To move from enterprise value to equity value, valuators add cash and non-operating assets and then subtract interest-bearing debt and similar liabilities.

In practical terms, excluding cash and debt ensures that net working capital reflects only the operating assets and liabilities necessary for day-to-day business activities, such as accounts receivable from customers, inventory required for production or sales, and prepaid expenses like insurance. On the liability side, only those directly tied to operations (e.g., accounts payable to suppliers and accrued operational expenses) are included. Items not related to core operations, such as cash, investments, loans, or tax liabilities, are omitted because they do not accurately represent the ongoing funding needed for operations.

Why is Cash Not Part of Enterprise Value and Why is it Excluded From Net Working Capital?

Enterprise value customarily includes accounts receivable, inventory, prepaid expenses, and accounts payable. Cash is generally excluded, as its treatment pertains more to financing decisions; whether a company retains or distributes it. Some companies may operate without cash balances and rely exclusively on lines of credit. Within the profession, it is widely accepted that enterprise value is calculated on a cash-free, debt-free basis to avoid distorted results. Due to the discretionary nature of cash and the high degree of variability associated with it, it is often preferable to exclude cash in arriving at an enterprise value.

A common question arises regarding whether all cash should be added back or only excess cash above working capital requirements or peer group norms. Practices vary, and no single standardized approach exists. However, treating all cash as an add-back can remove one area of subjectivity in arriving at a value conclusion.

This methodology aligns with the view that, if a company is profitable, it will generate positive net cash flow over the year. Despite fluctuations necessitating cash reserves for expense payments or temporary borrowings, such requirements are better viewed as financing decisions, especially when a line of credit is available. As discussed earlier, one rationale for adding all cash back is that, in practice, cash is typically excluded from purchase price calculations during transactions. In most deal structures, all cash accrues to the benefit of the seller, which further supports this approach.

How Does Net Working Capital Impact a Company’s Value?

Net working capital influences a company’s value in two principal ways. First, as of the valuation date, the company may have an excess or deficiency in net working capital. If there is excess net working capital (i.e., an amount above the level required for normal operations), this surplus is added to the final valuation to ascertain the company’s actual value. Conversely, if there is a deficiency (i.e., an amount below the operational requirement), this shortfall is deducted in determining the actual value. During mergers and acquisitions, buyers and sellers often negotiate a ‘target’ net working capital based on historical averages to ensure the company has sufficient resources to maintain its operations without either party being advantaged or disadvantaged at closing. Any difference from this target at the deal’s closing can result in purchase price adjustments. For example, if actual net working capital is above the target, the seller may receive an upward adjustment; if below, the purchase price might be reduced accordingly. This mechanism helps protect both sides from unexpected changes in the company’s short-term financial position. If this works in actual transactions, then we should consider the same in our valuations for other purposes.

Secondly, net working capital affects a company’s value by accounting for the investments necessary to support growth, particularly when applying the income approach. As the business expands, it typically must increase its net working capital to maintain higher accounts receivable and inventory levels required for greater sales volume and revenue. This reinvestment of profits into net working capital results in reduced cash available for distribution to shareholders, thereby impacting the calculated value under the income approach.

Key Items to Consider Regarding Net Working Capital

- Revenue and Growth: Organizations experiencing growth often need additional working capital to accommodate increased sales volume, manage accounts receivable, and finance inventory. Unmanaged rapid growth can place significant pressure on a company’s working capital position.

- Industry and Business Cycle: Working capital requirements vary across industries. Sectors such as manufacturing and retail generally demand higher levels of net working capital given their inventory needs and receivables management. Conversely, service-based sectors like consulting firms and legal practices typically require less working capital due to lower asset intensity. Furthermore, the business cycle stage can influence working capital needs.

- Seasonality: Companies with seasonal demand fluctuations may be required to sustain elevated working capital levels during peak periods to support larger inventories and higher accounts receivable balances.

- Supplier and Customer Relationships: The terms negotiated with suppliers and the average collection period from customers play a critical role in determining a company’s net working capital. Extended payment terms or delayed collections may result in cash being tied up within working capital.

- Benchmarking and Data Source: Industry data sources like ProSight (formerly RMA), MicroBilt, transaction databases, and guideline public company data (from sources like Tagnifi or Capital IQ), may require adjustments to align with specific working capital definitions. Practitioners must critically evaluate and modify these benchmarks as needed.

- Deferred Tax Assets and Liabilities: Deferred tax items can be misleading in working capital calculations, especially in distressed or liquidation scenarios. They should be carefully analyzed and adjusted where appropriate, which is another reason to carefully review working capital if all current assets and liabilities are used in the determination of ongoing working capital.

- Negative Working Capital as a Strategy: Some companies, such as Walmart and Dell, strategically use negative working capital to finance operations. This approach can be advantageous but requires careful management. From a cash flow perspective this may be an increase to value, but being aware of the additional risk it may pose is an important consideration.

- Cash Basis vs. Accrual Basis Accounting: Valuations for companies using cash-basis accounting may need to estimate the approximate accrual-based working capital. This ensures consistency and comparability in financial analysis with the data sources and for comparability to the discount rate.

- Valuation Method Consistency: Consistency in applying working capital adjustments across income, market, and asset approaches is essential. Discrepancies can lead to flawed conclusions and must be avoided.

Conclusion

Net working capital is a crucial element in business valuation; impacting both enterprise and equity values. By focusing on operating assets and liabilities, excluding cash and debt, net working capital provides a clearer picture of a company’s day-to-day financial health. It plays a significant role in mergers and acquisitions, where target net working capital is negotiated to ensure transaction closing targets. Additionally, net working capital influences a company’s value by accounting for necessary investments to support growth; affecting cash flow and overall valuation. Understanding and managing net working capital is essential for accurate business valuation and effective financial planning.

Gregory M. Clark, CPA, CVA, MAFF, is the Managing Member of GMC & Company. He specializes in valuation, financial forensics, M&A advisory, forensic accounting, damages, and further business and commercial litigation in a diverse range of industries. Mr. Clark serves as an expert witness for complex financial matters related to valuation, marital dissolution, shareholder disputes, damages, business litigation, commercial litigation, lost profits, and further matters requiring financial, valuation, and/or forensic accounting expertise. He is a frequent author and speaker on valuation, litigation advisory, business management, and other financial topics.

Mr. Clark can be contacted at (219) 554-9700 or by e-mail to greg@gmcandco.com.