The January Hangover

A 10-Day Fraud Detection Sprint That Protects Business Value

It is important to not only establish next steps but attempt to blur the line between fraud-driven forensic investigations and valuation to provide the connective tissue; explaining how they overlap resulting in misleading valuation calculations. In this article, the author shares a 10-day fraud detection “sprint” to identify the reliability of earnings and balance sheet integrity.

This past December, I authored a short article titled, “’Tis the Season (for Fraud): How Businesses Can Be On-Guard”[1], which discussed many of the tactics that are employed by fraudsters during those chaotic periods such as years-end and during the holidays when that “let’s just get it done” energy and overall fatigue can ultimately create all manners of financial nonsense down the road. While drafting the follow-up article, it occurred to me that it was important to not only establish those next steps but attempt to blur that line between fraud-driven forensic investigations and valuation to provide the connective tissue, and explain how they overlap resulting in misleading valuation calculations.

How Year-End Fraud Alters the Valuation Story

Year-end variances and holiday frauds are most often treated as an operational issue. It is something filed under “accounting headache,” that will likely be patched with a reversal entry and a quick policy reminder so it can be pushed aside; allowing the business to get back to what it considers the real work. What cannot be overlooked is that year-end fraud can create complications within a valuation when it distorts what the financial statements convey about operating performance, working capital, or risks the business might be susceptible to. While the incident may be viewed as non-material relative to reported revenue, it can still be material to overall value if it changes normalized earnings or creates uncertainty around the perceived cash flows. In addition, it can also signal weak controls that may increase the likelihood of future losses that could substantially affect projections and the company specific risk premia.

The implications of such seemingly modest “variances” carry across nearly every scenario where valuations are performed. In a transaction setting, a buyer may incorrectly interpret an expense spike driven by fraud as declining profitability, causing a response with a lower multiple or escrow demands. In a shareholder dispute or divorce scenario, they can become points of contention about what a company’s true earnings are and whether one party has benefited from a manipulated cash flow. In estate and gift matters, a temporary distortion generated by fraud can impact the defensibility of a valuation if it changes the baseline cash flow of the year on which the future cash flows are based. Lastly, in litigation support, the issue is not only the dollar impact but whether the records and representations can be sufficiently relied upon without qualification or adjustment.

Fraud can impact value through multiple channels, and that channel will often matter more than the amount. A diverted vendor payment may appear as just another routine expense while it quietly alters EBITDA. A business e-mail compromise scam (BEC) where someone uses e-mail to trick someone into wiring funds to a fraudulent bank account may reduce cash and create a messy recoverability timeline. A payroll diversion scheme can later distort labor ratios as well as gross margin trends. All of these could become evidence of an unstable control environment, which is something that a buyer, judge, mediator, or opposing expert may treat as a legitimate risk factor.

Consider how the same fraud incident may look in each of the following three scenarios. In an M&A context, that late-year spike observed in “outside services” from fraudulent invoices might look like structural overhead creep. While in a divorce context, those same invoices could be argued as the dissipation of marital assets if they were paid to a party-connected account or used to move money out of reach of the now perceived injured spouse. Meanwhile, in a shareholder dispute, questionable disbursements such as these might become a narrative about the manipulation of reported earnings to influence the buyout price.

What ties these together is a singular valuation principle: if the historical financials are distorted by one-time or ongoing improper items, you either adjust the economics (normalized earnings and working capital) or you adjust the risk (discount rate, multiple, or credibility of forecasts). Often, you do both.

A 10-Day Detection Sprint (Start Any Time)

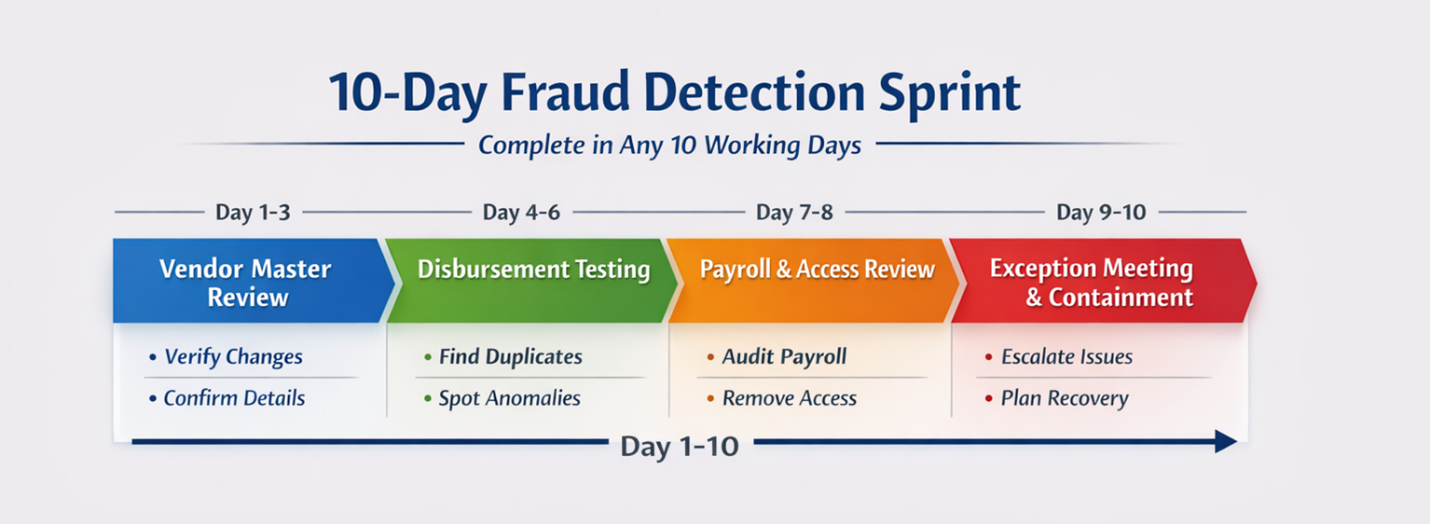

One practical way to reduce this potential exposure is to run a structured “10-day detection sprint” once year-end activity has finally slowed down. It is intentionally scoped; not meant to be a full forensic engagement, nor would it be considered a re-audit of the year. It is instead a targeted review designed to identify specific types of year-end frauds and process failures that most often tend to affect such measurements as earnings quality, working capital, and the perceived risk of a company.

This sprint is most effective when it is framed as an exercise in “earnings reliability and balance sheet integrity” instead of “looking for fraud”. In many environments, framing it in that manner reduces defensiveness and increases access to the right records without the nervousness the word “fraud” brings to the table. The sprint can be completed in any 10 working days and is best organized around three focused workstreams: “vendor master activity”, “disbursement testing”, and “payroll/access cleanup”. There is then a fourth step, “exception disposition”, in which the items identified are evaluated, resolved, and translated into clear decisions.

Days 1–3: Vendor Master and Payment Detail Change—Where Value Leaks Quietly

Vendor impersonation and invoice schemes usually involve a simple move, e.g., change the bank details and/or contact information, then send a credible invoice to be processed during those year-end time pressures. From the valuation perspective, the loss is now embedded within recurring expense categories. If it is not identified and remains, it depresses EBITDA and can reduce perceived profitability. In addition, the accounting treatment becomes inconsistent. Sometimes the business places the item in an “other receivable” bucket as a potential future recovery. Sometimes it leaves it in SG&A. Sometimes it reverses and reissues payments later. Any of those treatments can distort period-to-period comparability and analysis, as well as the defensibility of normalized results. It is important to note that many losses attributed to fraud get buried in SG&A as “miscellaneous”, “outside services”, or “professional fees”.

Imagine a buyer reviewing 12-month financials and seeing a notable increase in the vendor costs. The buyer may treat it as an ongoing run rate problem and change the valuation multiple if the seller cannot quickly provide the explanation that the increase was driven by a nonrecurring fraudulent event that has been remediated. In the context of a shareholder dispute, evidence of new vendors or vendor name variations can raise questions about whether payments may have been diverted intentionally. If internal controls are potentially weak, the company’s stated results may be unreliable. While in the context of a divorce, these vendor anomalies can be yet another allegation against the spouse owning the business and, subsequently, yet another point for tracing to identify where the money went.

It is easy to see why reviewing vendor change logs and independently verifying banking changes has valuation relevance. You are not only validating payments, you are also validating the credibility of the dates themselves that are used to compute value.

Days 4–6: Disbursement Testing—When the Balance Sheet and EBITDA Stop Agreeing

BEC and disbursement fraud will often leave behind a pattern. They stand out as payments made under exception, approvals that bypass standard policy, and transactions that seem to be designed to avoid established approval thresholds. Those patterns matter because they can create conflicting narratives between the P&L and the balance sheet.

As an example, a BEC wire could reduce cash immediately but not appear as a loss until much later, depending on how that particular transaction is booked. If management records a temporary receivable while they pursue recovery, this can inflate assets and improve working capital metrics artificially until that receivable is later deemed a write off. In a deal context, it can complicate net working capital targets and associated true-up debates. A buyer may decide to argue that the receivable is not a true operating asset while the seller may argue that recovery is likely. The valuation professional’s role is to separate economic reality from accounting optimism and reflect both in the valuation analysis and narrative.

In litigation settings, disbursement anomalies can also become a factor which intensifies questions about whether someone (or their records) are believable and reliable. If approvals were informal or the documentation is inconsistent, an opposing expert may challenge the reliability of the records and management representations that were used in the valuation. In divorce and shareholder cases, suspicious disbursements can raise broader tracing and characterization questions, particularly when payments are routed to new recipients or labeled vaguely in memo fields.

The valuation takeaway here is that disbursement testing is not just about finding a bad payment. Disbursement testing is about ensuring cash outflows are reflected in the right period, the right classification, and tell the right economic story.

Days 7–8: Payroll and Seasonal Staffing—How Labor Issues Distort Margin and Forecast Credibility

Payroll issues are often dismissed in valuation discussions, but they can materially affect gross margin analysis and forecast credibility. This is especially true for businesses with multiple sites and high turnover (or seasonal hiring cycles). Fraud in this area may take the form of direct deposit diversion, fictitious employees, or onboarding scams during periods of high hiring volume where new names may not raise questions.

From the valuation standpoint, payroll fraud can tell a false margin story. If labor costs are inflated by improper payments, then EBITDA is understated and the business may appear less profitable than it is. In contrast, when improper costs are deferred, misclassified, or even reversed without any clear support, the period-to-period comparability becomes entirely unreliable and any claim of a normalized margin is harder to substantiate.

In an M&A deal, unusual payroll swings late in the year can make forecasts harder to trust; especially when there is no clear explanation for shifting labor ratios, or other issues such as a bump in manual checks, or a spike in direct deposit changes. In shareholder disputes, those same types of anomalies can draw scrutiny to established oversight over whether payment practices were used to influence the buyout number. In divorce matters, payroll irregularities can also tie into lifestyle analysis when spending patterns do not square with the income being claimed.

Payroll and user-access cleanup matters for the same reason. Weak access control is a forward-looking risk and not just a cleanup item. If seasonal staff were able to keep their credentials after they were gone, the exposure quickly extends beyond payroll into the accounting system, vendor records, and customer data. It is not merely “one bad event”. This is exactly the kinds of weaknesses that also minimizes confidence in the reporting and make projected cash flows harder to rely on.

Days 9–10: Exception Disposition—Where Findings Become Valuation Decisions

So, what do you do with what the sprint turns up? You close it out with a formal disposition step because this is the point where fraud work transitions into valuation work. Each exception needs a clearly defined outcome and a clearly defined treatment that can be defended.

If the item is fully supported and resolves cleanly, then document the support and move on. Congratulations. Nothing changes in the model and you can continue.

When an item has been corrected (i.e., reversed, reclassified, recovered, or routed through an insurance/bank claim), then the analysis should follow the properly stated results, not whatever temporary accounting treatment was employed while people were scrambling.

If the item cannot be cleared or is still developing, you should decide how it should flow (and be documented) through the valuation. Depending on the established facts, that might mean a normalization decision, a working capital adjustment, or an explicit risk rationale that attempts to explain why the control environment and the financials should warrant more caution than the headline numbers might suggest.

As always, different contexts drive different decisions. In a transaction, the unresolved exceptions may be enough to warrant a sensitivity analysis. In litigation, the same uncertainty may justify additional testing and might even have some influence on how heavily you rely on management forecasts. In divorce or shareholder disputes, unresolved items may shift to questions about who benefited and whether transactions reflect dissipation or personal benefit.

Valuation Workpaper Tie-In—Making the Sprint Count

This detection sprint is only as valuable as what it changes in the valuation and its workpapers. The practical tie-in is straightforward in that the sprint produces a documented set of exceptions and resolutions that can be translated into three places value decisions typically live: earnings normalization, working capital and balance sheet integrity, and the risk narrative.

On the earnings normalization side, the sprint is a reality check. When the item can be tied to support and is clearly a one-time and well-defined event, it can be handled like any other standard normalization adjustment. However, if it keeps showing up or points to a likely control gap that has not been fixed, an add-back would likely be hard to defend. The real value of the work and this sprint is not to establish a tidy EBITDA bridge, but documentation that supports a more cautious view of the forecast.

On the balance sheet side, the sprint can explain why assets or liabilities became messy in Q4 and early January. Issues with disbursements can create recoverables or other “parking lot” accounts such as other receivables or unapplied cash. In transactions, those balances often become negotiation points. The same question in disputes and estate valuation is whether the balance sheet reflects reality. Sprint documentation supports classification (operating vs non-operating), collectability assessments, and decisions about impairments or exclusions.

The sprint gives you something you can stand behind on the risk side. Even when the dollars are too small to move EBITDA, identifying failures that repeat can provide important details about the examined control environment. Those patterns can help establish how much weight you ultimately decide to put on management’s representations and projections.

A simple way to document findings in valuation workpapers would be with a brief “Sprint Exceptions Summary” exhibit. This exhibit should list the following: what was flagged, what support was obtained, how it was resolved, and how it impacted (if at all) normalized earnings, balance sheet treatment, and risk factors. This provides defensibility when you are answering questions on diligence, responding to counsel, or supporting your analysis before a trier of fact.

Closing

Year-end fraud is not only a December operational risk; when left unattended, it is a valuation risk that can distort earnings and undermine confidence in the financial narrative. Our suggested 10-day detection sprint can be completed any time (preferably in January) and gives businesses and valuation professionals a way to identify what slipped through year-end pressure. They can then decide, in a defensible way, whether the solution arrived at is an economic adjustment, a balance sheet adjustment, a risk adjustment, or a scope adjustment. In every context, whether it is transaction, dispute, divorce, estate, or internal planning, it will still end up the same: a valuation conclusion that better reflects reality and (hopefully) a business that is harder to exploit next year.

[1] https://deandorton.com/tis-the-season-for-fraud-how-businesses-can-be-on-gaurd/

Jeff A. Kolbfleisch, MSFFE, CFE, CCI, is a Forensic and Valuation Services Consultant with Dean Dorton, providing litigation support in areas of business valuation, forensic accounting, fraud detection, and cryptocurrency tracing.

Mr. Kolbfleisch can be contacted at (904) 479-0108 or by e-mail to jkolbfleisch@deandorton.com.