Terms of Art

Understanding the Language of Chapter 11 Cramdown

This article will examine terms of art used in a Chapter 11 cramdown. These terms go hand in hand during a contested or cramdown hearing. The court will work to assure that the bankruptcy definition of these terms is met before confirming a plan. Any expert expecting to testify at a cramdown hearing should have a working knowledge of their meaning.

Terms of art are common in our society. Each field or profession contains words or phrases that have a precise or specialized meaning for them. For those working as a financial expert in litigation, it is no different. Many of the terms of art have been defined through legislation and legal precedent. Any financial expert entering this environment should become aware of how certain terms apply.

This article will examine terms of art used in a Chapter 11 cramdown. These terms go hand in hand during a contested or cramdown hearing. The court will work to assure that the bankruptcy definition of these terms is met before confirming a plan. Any expert expecting to testify at a cramdown hearing should have a working knowledge of their meaning.

Cramdown/Impaired Creditors

Chapter 11 is primarily used by business enterprises wanting to continue their operations.1 Under this format, a reorganization plan is proposed to the bankruptcy court. If the reorganization plan is confirmed by the judge, the debtor makes payments directly to its creditors until the terms of the repayment plan are fulfilled. Through the Chapter 11 reorganization process, a debtor may reduce its debt obligations, terminate burdensome contracts and leases, recover assets, and rescale operations, ultimately emerging as a reorganized business with less debt.

In bankruptcy reorganizations, creditors who have been deemed impaired have the right to contest the reorganization plan. Being impaired means the reorganization plan alters the contractual rights of a class of claim holders. Most often, this means that under the reorganization plan a creditor will not be paid in accordance with the terms of a loan or contract as agreed prior to the bankruptcy. If the plan does not change the rights of a class of claim holders, the court deems the creditors to be unimpaired and to have automatically accepted the reorganization plan.

Creditor objections vary from structural issues to the duration and/or interest rate to be paid on a specific debt, the value of the collateral, or if the repayment plan is feasible (i.e., can the debtor fulfill the repayment obligations). Should an impaired creditor file an objection (e.g., requesting a greater interest rate on a debt to be repaid over time), a court hearing is held in which the debtor and creditor argue their positions. These contested hearings are often referred to as âcramdown hearingsâ because the debtor is asking that the terms of the reorganization plan be upheld and crammed down the creditor. Not all bankruptcy reorganization plans are contested. However, when an objection is filed, the cramdown hearing becomes very important. This is because the results of the hearing will, more likely than not, determine whether a reorganization plan will be confirmed or denied.

Unfair Discrimination/Fair and Equitable

Section 1129 (b) of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code allows a bankruptcy reorganization plan to be confirmed over the dissent of the impaired classes if the plan does not unfairly discriminate and is fair and equitable. âA plan may provide for different treatment for classes of equal rank in priority as long as such treatment does not rise to the level of unfair discrimination.â2

A plan unfairly discriminates if one class of equal rank and priority receives payment of greater value under the plan than another objecting class without reasonable justification. The reorganization plan may provide for different treatment for classes of equal rank and priority as long as the different treatment is not deemed unfair. It is the judge who decides if the reorganization plan unfairly discriminates or not.

The Bankruptcy Code calls for the âfair and equitableâ treatment of any impaired dissenting class. To be fair and equitable, the creditor must not be compelled to accept less than full compensation for its claim while a more junior creditor or interest holder receives compensation or retains interest in the debtor.

The language of the Bankruptcy Act provides the language for what is fair and equitable treatment of an impaired creditor.

âFor the purpose of this subsection, the condition that a plan be fair and equitable with respect to a class includes the following requirement:

(A) With respect to a class of secured claims, the plan providesâ

(i)(I) that the holders of such claims retain the liens securing such claims, whether the property subject to such liens is retained by the debtor or transferred to another entity, to the extent of the allowed amount of such claim; and

(II) that each hold of a claim of such class receive on account of such claim deferred cash payments totaling at least the allowed amount of such claim, of a value, as of the effective date of the plan, or at least the value of such holderâs interest in the estateâs interest in such property; (ii) for the sale, subject to section 363 (k) of this title, of any property that is subject to liens securing such claims, free and clear of such liens, with such liens to attach to the proceeds of such sale, and the treatment of such liens on proceeds under clause (i) and (iii) of this subparagraph; or (iii) for the realization by such holders of the indubitable equivalent of such claimsâ3

The language means a plan can be confirmed if the secured creditor receives a lien on the collateral that has been securing the claim and is providing a series of payments which are equal to the present value of the claim. It also allows for the sale of the collateral so long as the proceeds from the sale go to retire the outstanding portion of the claim. Finally, the debtor may swap the collateral for another of equal value or provide some form of security for the repayment of the claim, the indubitable equivalent of the claims.

As with determining unfair discrimination, the judge reviewing the reorganization plan decides if the plan is fair and equitable.

Feasiblity

While judges decide what is âunfair discriminationâ and âfair and equitableâ without input from financial experts, expertsâ insight into feasibility and present value are often a part of a cramdown analysis.

When a business in Chapter 11 files a reorganization plan, the court reviews it to insure the plan has a reasonable chance of survival once the plan is confirmed and the debtor has moved out from under the protection of the bankruptcy code. In other words, the plan must be feasible. It must demonstrate that the business will be a viable entity, one that is able to meet its repayment schedule as it moves forward.

âCourts do not need to determine a planâs success will be a âsure thingâ in order to make a feasibility finding, but courts also do not want to confirm a speculative plan just to find the company back in bankruptcy a second time. If the expert cannot provide a âfeasibleâ financial plan to the court, its reorganization plan may not be approved and this failure can result in liquidation of the companyâ4

In general terms, a feasibility study is defined as an analysis of the ability to complete a project successfully, taking into account legal, economic, technological, scheduling and other factors. âRather than just diving into a project and hoping for the best, a feasibility study allows project managers to investigate the possible negative and positive outcomes of a project before investing time and money.â5

The first part of a feasibility study in a cramdown situation is similar to one performed on a non-bankrupt company. The analysis should consider the adequacy of the debtorâs capital structure, its earnings power, ability and commitment of management, economic conditions, the current credit markets, and the retention of its clients. In the end, the analysis will determine whether the debtor will be able to have sufficient cash on hand to pay its debts over the proposed repayment period.

The study should also consider benefits arising from confirmation of the plan. This may include improving profitability by increasing revenue or reducing expenses and/or eliminating unprofitable products or services.

Finally, the expert needs to be aware of why the company is in bankruptcy. This could be due to external factors (e.g., increased competition or product obsolescence), internal factors (e.g., poor management or undercapitalization) or a combination of both. These factors play an important role in assessing the ability of the debtor to move out of bankruptcy, operate profitably, and repay its debts as scheduled in the repayment plan.

For an expert determining the feasibility of a reorganization plan, the reliability of the debtorâs previous cash flow projections, and the reasonableness of assumptions made in estimating future cash flow will need to be assessed. To paraphrase the opinion from Adelphia Communications, a confirmable reorganization plan only works when the debtor has accurate projections of its future cash flow. These projections should not be tainted by fraud and able to show positive cash flows.6

For these reasons, âa feasibility opinion should be more than just a ârubber stampâ prepared by the financial expert. The opinion should be credible and reliable, and should give a basis for its calculations, conclusions, and opinions.â7

Present Value

One of the most common assignments given to financial experts in Chapter 11 cramdown matters is determining the appropriate interest rate to provide for the present value of the impaired creditorâs claim. An expert accepting such an assignment must be aware of what âpresent valueâ means in cramdown matters.

Since 1916, the U.S. Supreme Court has noted the âtime value of moneyâ and the need to discount future losses to present value. âSo far as a verdict is based upon deprivation of future benefits, it will afford more than compensation if it be made up by aggregating the benefits without taking account of the earning power of money that is presently awarded. It is self-evident that a given sum of money in hand is worth more than the like sum of money payable in the future.â8 The Chesapeake court went on to say that the âsafest and bestâ interest rate should be used for discounting to present value future losses in personal damages cases.

In 2003, the Supreme Court took up the issue of determining the interest rate to be used to provide the present value of a bankruptcy claim to be paid over time.9 In the Till decision, the court noted the difficulty in addressing this issue. âThe Bankruptcy Code provides little guidance as to which rates of interest advocated by the four opinions in this caseâŚCongress had in mind when it adopted the cramdown provision.10 That provision, 11 U.S.C. 1325(a)(5)(B) does not mention the term âdiscount rateâ or the word âinterest.â Rather, it simply requires bankruptcy courts to ensure that the property to be distributed to a particular secured creditor over the life of the bankruptcy plan has a total âvalue, as of the effective date of the plan,â that equals or exceeds the value of the creditorâs allowed secured claim.â11

One of the questions often asked of financial experts providing cramdown interest rate testimony is, âWill this interest rate provide for the present value of the secured claim?â Having determined the interest rate and believing it to be appropriate for this payment stream, the expert will always answer, âYes.â From a financial or economic perspective, the question doesnât make much sense. However, it provides a view to the nuances in the use of the term âpresent valueâ in bankruptcy cases.

As noted by the Chesapeake court, âIt is self-evident that a given sum of money in hand is worth more than the like sum of money payable in the future.â (Chesapeake, 489) Therefore, it would appear some form of interest should be paid along with the principal in this series of future payments to provide for the amount of the claim as of the effective date.

Bankruptcy courts have addressed the use of present value and its application to the language in 1129 (b). âThe Chapter 11 cramdown provision has been interpreted to require that the total deferred payments have a present value equal to the amount of the secured claim.â12

âUpon confirmation of a plan of reorganization, a new bargain is made, albeit not at armsâ length but under the provisions of the Bankruptcy Code, and 1129 (b) requires that a creditor simply receive the âpresent valueâ of his secured claim for the confirmation to succeed. Therefore, with regard to over-secured commercial loans, this Court will employ the formula used by the market to derive the appropriate interest rate. Employing a âmarket formulaâ will achieve the Supreme Courtâs underlying purpose in Till of ensuring that secured creditors are compensated for the âtime value of money and the risk of defaultâ by the way of objective assessment, while at the same time employing on-the-ground insight of an effective market, where it exists.â13

Since Till, many bankruptcy courts have chosen to apply a formula approach for determining a cramdown interest rate in even Chapter 11 cases. âWhile many courts have chosen to apply the Till pluralityâs formula method under Chapter 11, they have done so because they were persuaded by the pluralityâs reasoning, not because they considered Till binding.â14

The Till decision provides the following guidance. A bankruptcy court should: âselect a rate high enough to compensate the creditor for its risk but not high enough as to doom the plan. If the court determines that the likelihood of default is so high as to necessitate an âeye-poppingâ [cite omitted] interest rate, the plan probably should not be confirmed.â15

The Supreme Court hoped the wide acceptance of the formula approach would reduce differences over interest rates and what discount rate allows for present value in bankruptcy matters. Of course, that did not happen.

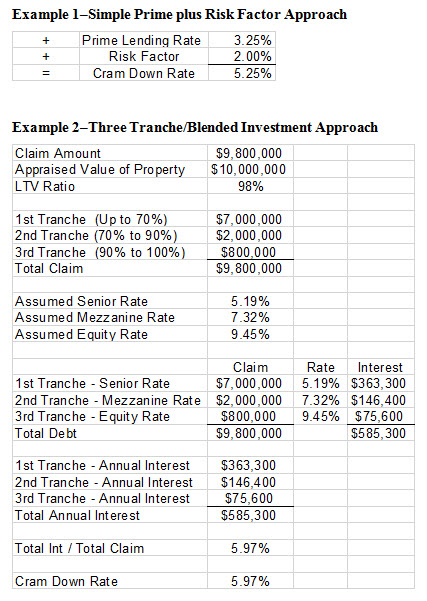

A review of methods accepted by courts used in determining the appropriate cramdown interest rate shows great differences in the âtime value of money.â Methods accepted by bankruptcy courts have ranged from as simple as applying the Till prime lending rate plus 1% to 3% formula to complex three tranche analyses.

The following are two ways the formula approach has been used to determine the interest rate assumed to provide for the present value of a secured claim to an impaired creditor.16

Conclusion

Terms of art are found in all professions and fields of work. Chapter 11 bankruptcy is no different. For financial experts working in business bankruptcy, a knowledge and understanding of these terms of art is important. Whether the terms relate to issues to be argued by the attorneys and decided by a judge or more closely tied to the role being played by the expert, greater knowledge of bankruptcy language will assist experts in fulfilling their assignment.

Most experts become involved in bankruptcy matters when the reorganization plan is contested by one of the impaired creditor classes. These situations may lead to an expert testifying as a part of a cramdown hearing. Understanding what is expected with a feasibility study or determining an interest rate that provides for the present value of a claim allows the expert to ask the appropriate questions and provide the expected analysis. Also understanding how prior courts have viewed the methods applied by other financial experts adds value to the expertâs work.

This article provides explanations for terms of art related to Chapter 11 cramdown situations. These explanations should provide for an initial understanding of the language being used by the attorneys and the bankruptcy judge. Through this understanding, an expert should be better prepared to provide information beneficial to the court and its assessment of the reorganization plan. And through this result, the expert should be able to provide a better product to his or her client.

[1] As opposed to being placed in Chapter 7 which calls for liquidating the businessâ assets and paying the secured and unsecured creditors with the proceeds.

[2] Kaplan, 1

[3] 11 U.S.C. 1129 (b)(2)(A)

[4] Suker, 1

[5] Investopediaâfeasibility study

[6] In Re: Adelphia Communications et. al.

[7] Suker, 1

[8] Chesapeake, 489

[9] The Till decision calls for the formula approach to be used in determining the interest rate to be paid to an impaired secured creditor in Chapter 13 cramdown situations. The decision has instructive for Chapter 11 cramdown cases as well.

[10] Formula, coerced loan, presumptive contract, and cost of funds are the four methods for determining a cramdown interest rate discussed in the Till decision.

[11] Till, 473-474

[12] In re: T-H New Orleans, LP, 800

[13] In re: SJT Ventures, 4

[14] In re: Texas Grand Prairie Hotel Realty, LLC, 14

[15] Till, 480-481

[16] See âCommercial Real Estate, Chapter 11 Bankruptcy, Cram Down Interest Rates,â Parts 1 & 2, Quick Read, 5/27/2015, 6/3/2015 for more detailed discussion on determining cramdown interest rates.

Allyn Needham, Ph.D., CEA, is a principal at Shipp, Needham & Durham, LLC (Fort Worth, Texas). For the past 18 years, he has worked in the area of litigation support. As an expert, he has testified on various matters relating to commercial damages, personal damages, business bankruptcy and business valuation. Dr. Needham has published articles in the area of financial economics and forensic economics and provided continuing education presentations at professional economic, vocational rehabilitation and bar association meetings.

Dr. Needham can be reached at e-mail: aneedham@shippneedham.com, or phone (817) 348-0213.