Was the Showboat Closed to Steal Customers?

This is the final installment of the four-part series highlighting some of the key investigation issues and findings of the Examiner’s report. In this article, the author explores the claim that CEC inappropriately elected to close the Showboat Atlantic City casino and diverted its customers to Harrah’s Atlantic City casino.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]Resources:

Introduction To Fraud Risk Management

Fraud Deterrence And Fraud Detection

Introduction to Financial Forensics in Bankruptcy Proceedings

Valuation of Distressed Businesses and Plan of Reorganization

Litigation for Bankruptcy and Insolvency

[/su_pullquote]

This article is the final installment of the four-part series highlighting some of the key investigation issues and findings of the Examiner’s report.[1] In this article, the author explores the claim that CEC inappropriately elected to close the Showboat Atlantic City casino and diverted its customers to Harrah’s Atlantic City casino.

Background

Caesars Entertainment Operating Company (CEOC or the Debtor), which owned and managed a number of Caesars’ casino properties, filed for bankruptcy protection in January 2015. CEOC was a subsidiary of Caesars Entertainment Corp. (Holdco or CEC) which also owned casino properties through two other subsidiaries: Caesars Entertainment Resort Properties (CERP) and Caesars Growth Partners (CGP). In total, the Caesars gaming empire consisted of 43 casino properties, of which 28 were owned by CEOC.

The Debtor engaged in a series of complex sales of casinos and intellectual property as well as financings and related party transactions in the years prior to the bankruptcy. After the bankruptcy filing, an Examiner[2] was appointed to investigate and report on various CEOC pre-petition transactions. Alvarez & Marsal (A&M) was retained as financial advisor to the Examiner. The Examiner concluded that the value of claims related to fraudulent transfers, breaches of fiduciary duty, aiding and abetting breaches of Caesars management and its sponsors, and other actions ranged between $3.6 billion to $5.1 billion.[3],[4]

Location, Location, Location[5]

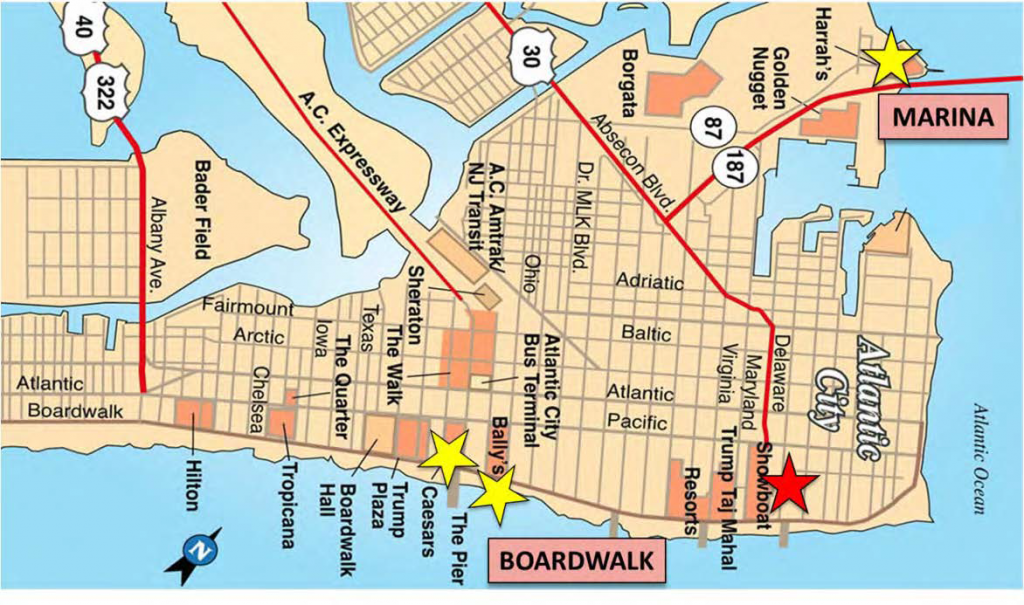

As shown below, there are two distinct casino areas in Atlantic City: the Boardwalk and the Marina District. The traditional tourist area—the Boardwalk—is on the beach and includes: Caesars Atlantic City, Bally’s Atlantic City, and the Showboat (CEOC-owned properties and Debtors). While the beach, Boardwalk, and casinos remain popular draws, much of the area surrounding the Boardwalk properties is depressed and crime-ridden. The newer Marina District is more upscale and includes: Harrah’s Atlantic City (a CERP-owned property and non-Debtor), the Borgata, and the Golden Nugget, as well as the boutique Water Club hotel.

Figure 1: Map of Atlantic City and Location of CEC’s Properties[6]

The Steep and Protracted Decline in Atlantic City Gaming Revenue[7]

Between 2006 and 2014, total gaming revenue in the Atlantic City market fell more than 47 percent and showed no sign of recovering. The supply of casinos far exceeded the demand, and many properties, not just Caesars’ properties, were experiencing financial difficulty. CEC and the Sponsors were aware of Atlantic City market trends, and strategies to cope with the decline in revenue, oversupply, and increased competition from neighboring states was a topic of nearly constant analysis and discussion.

Caesars’ Atlantic City Assessment and Decision to Close Showboat[8]

The performance of CEC’s Atlantic City properties was putting financial pressure on the company. An assessment of the Atlantic City market undertaken in January 2014 clearly showed that CEC needed to consolidate its Atlantic City properties to improve the performance of all the Caesars casinos. Management actively evaluated, analyzed, and discussed a variety of options and scenarios without regard to whether a property was a CERP or a CEOC property, including:

- Selling versus closing the Showboat;

- A timeshare hotel deal with Wyndham for the Showboat;

- Closing all or a portion of Bally’s Atlantic City;

- Acquiring Revel and retaining the Showboat; and

- Acquiring Trump Plaza with the Showboat sale versus closure.

Showboat’s Undesirable Location and Poor Performance Was Apparent

The Showboat was located a significant distance from the center of the Boardwalk area, and center Boardwalk was a more desirable location, with the highway flowing directly into it. There was also significant existing and proposed non-gaming development in the heart of the Boardwalk (where Caesars Atlantic City and Bally’s Atlantic City were located), including the Pier, a possible park, the Bass Pro Shops retail development, and the Marketplace, all of which would have the potential to benefit those two casinos, but not the Showboat. Lastly, at the time, two properties near the Showboat—Trump Taj Mahal and the Revel—were distressed and likely to close. Their closing would have left the Showboat alone at the far end of the Boardwalk.

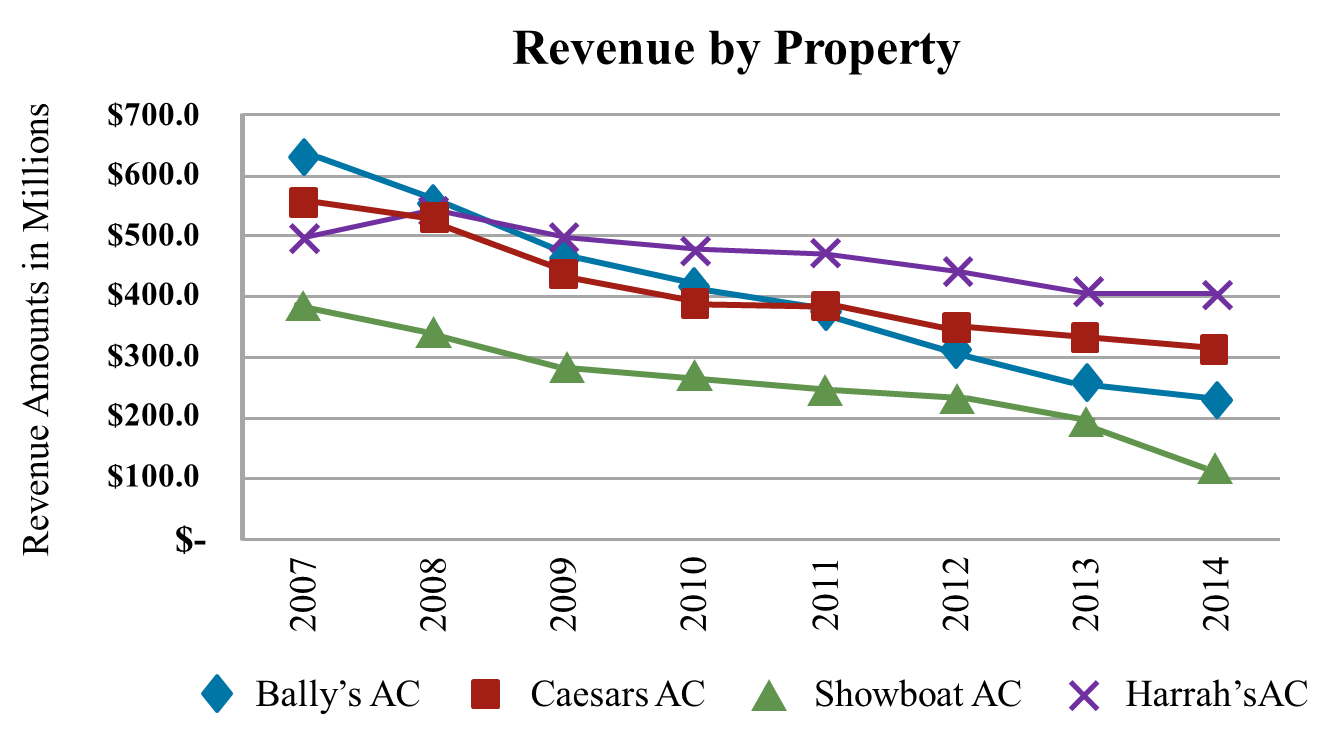

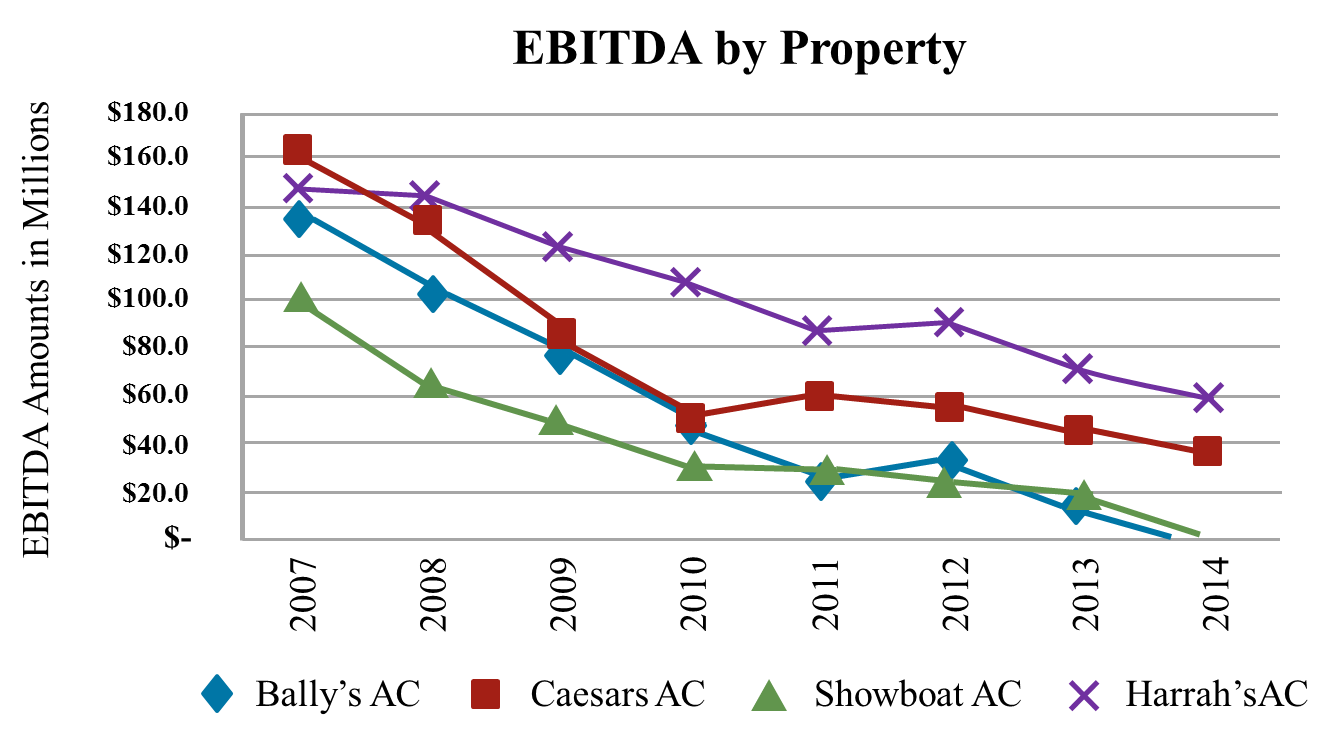

In addition, Showboat’s performance was worse than the other CEOC properties; its earnings had declined precipitously since 2007 and were projected to continue to decline, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3:

Figure 2: Revenue by Property for Atlantic City Properties

Figure 3: EBITDA by Property for Atlantic City Properties

Other Options Were Considered

Closing Caesars Atlantic City, the “flagship,” was not a feasible option, because, among other reasons, Caesars Atlantic City had a “draw because of its brand.” Approximately 25 percent of Caesars Atlantic City’s gross gaming revenue was from lodgers at Bally’s Atlantic City, a property physically connected to Caesars, thus closing Bally’s Atlantic City would have removed this source of Caesars Atlantic City casino customers and left a shuttered casino attached to the “flagship.” Closing Harrah’s Atlantic City was not an option because, among other reasons, extensive investments had already been made in that property, it was the best Caesars hotel property in Atlantic City, and it was in the Marina District that attracted more upscale customers.

Caesars’ Strategy to Address Market Decline and Poor Performance

As a result, a strategy was formulated that included rationalizing supply through property closures and inducing mixed-use (non-gaming) real estate investment to improve the performance of the remaining assets in the market.[9] Ultimately, CEC determined that the Showboat was the most logical property to close because of its location, declining earnings, and other practical considerations, including potential impact on other CEC Atlantic City properties.

Creditors’ Concerns about the Showboat Closure

Various creditors raised concerns about the wisdom and fairness to CEOC of closing Showboat.[10] The Examiner investigated the decision to close the Showboat as opposed to another CEC property in Atlantic City.[11] In connection with the closure of the Showboat, Caesars developed and implemented a detailed marketing plan in order to retain the Showboat’s customers within the Caesars network.[12] Various creditor groups criticized Caesars for failing to ensure that CEOC (the owner of the Showboat and a Debtor entity) was compensated for any of its customers who ended up at Harrah’s Atlantic City (a non-Debtor property)—or, put another way, for including Harrah’s Atlantic City in the Showboat’s customer retention marketing effort.[13]

The CEC Board of Directors approved the Showboat closure in February 2014, announced its decision on June 27, 2014 and closed the property on August 31, 2014.[14] Caesars subsequently sold the Showboat to Stockton College for $18 million on December 12, 2014.[15] Following the closure, the financial performance improved for Caesars Atlantic City properties overall, and the ones owned by CEOC.[16]

The Examiner concluded that the decision to close the Showboat was a reasonable business decision based upon a detailed analysis which considered the three CEOC properties and the one CERP property. If the decision had been made solely considering the three CEOC properties (i.e., Showboat, Bally’s Atlantic City, and Caesars Atlantic City) and excluding CERP’s property (Harrah’s Atlantic City), it is hard to imagine a different result as the Showboat remained the logical choice. As a result, the decision to close the Showboat did not give rise to any viable claim.[17]

Creditors’ Even More Concerned with the Diversion of Customers[18]

Certain creditors asserted that Caesars implemented a marketing plan and manipulated room rates to direct Showboats customers to Harrah’s Atlantic City following Showboat’s closure.[19]

Not surprisingly, Caesars designed and implemented a marketing plan to retain Showboat’s customers. Following an initial phase focused on preserving revenues at Showboat prior to closure, Caesars moved towards a more targeted approach that leveraged the vast amount of customer data collected via the Total Rewards program. As discussed in Part 3 of this series, Caesars utilized a loyalty programed called Total Rewards and maintained a sophisticated database containing a huge amount of customer information. Using this customer information, Caesars constructed a marketing plan focused primarily on customers dominant to Showboat, as those were the customers most at risk of leaving the Caesars network.

Generally, the marketing strategy was to identify the secondary property preference for each Showboat-dominant customer and provide marketing offers for that property. To the extent that a Showboat-dominant customer did not have a secondary preference, the customer was provided offers to all three remaining properties. Caesars analyzed historical customer data for Showboat-dominant customers to evaluate gaming preferences and developed a marketing strategy based on that data. The customer data was segmented by the percentage of market Theo[20] in the Atlantic City market:

- Customers with greater than 75 percent of their market theoretical revenue at the Showboat were identified as not having a secondary property preference in the Atlantic City market. These customers received offers to all three remaining properties in Atlantic City.

- For customers with less than 75 percent of their theoretical revenue at the Showboat, Caesars identified the customer’s secondary property preferences. To the extent a customer had only one secondary preference, this secondary property became the customer’s dominant property and he or she received offers to that property.

- For customers with more than one historical secondary preference, Caesars assigned the new dominant property and provided offers based on the customer’s highest average daily win (ADW) among the secondary properties.

- For customers whose historical secondary preference was the Showboat, the marketing plan was to direct these customers to the “opposite” location in Atlantic City, i.e., the Marina District versus the Boardwalk.

The marketing plan was prepared without regard to the corporate ownership of any of the properties involved. Caesars employees viewed marketing efforts for Atlantic City as a means to benefit the entire Caesars network, irrespective of the corporate ownership of any property.

In addition, many of the casino “hosts” who had relationships with the Showboat VIP customers were transferred to other properties based on how the data suggested those customers would migrate. By moving hosts in this way, Caesars management attempted to maximize the chance of retaining those customers. The end result was that most of the casino “hosts” were transferred to Harrah’s Atlantic City.

However, Caesars Transferred Value Away from the Creditors by Diverting Showboat’s Customers to a Non-Debtor Property[21]

Despite the fact the marketing plan was agnostic as to the corporate ownership of each property, CEOC was clearly insolvent[22] at the time of the Showboat closure and implementation of the marketing plan thus should be entitled to compensation to the extent the CEOC customers were diverted to a non-Debtor property. Think of it this way: would a business close shop and give its customer list away for no value?

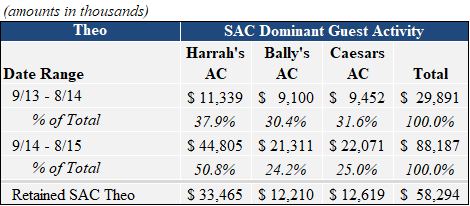

To assess this claim, the Examiner (and A&M, serving as financial advisor) evaluated the historical Cross-Play[23] of the Caesars Atlantic City properties relative to the Showboat (SAC) dominant customers gaming activity after the property’s closure. Figure 4 details the Theo Cross-Play behavior of the SAC dominant customers as of June 2014 and segments the data to capture the Theo Cross-Play activity of those same customers for the period of September 2013 through August 2014 (12 months prior to closure) compared to September 2014 through August 2015 (12 months after closure):

Figure 4: Cross-Play Summary for SAC Dominant Guest

After the Showboat closure, the remaining Caesars properties in the Atlantic City market captured approximately $88.2 million of the Theo revenue associated with the Showboat dominant customers. Of this amount, approximately 50.8 percent of the Theo revenue went to Harrah’s Atlantic City after the closure, as compared to 37.9 percent prior to the closure. As such, Harrah’s Atlantic City received what appears to be a disproportionate share of Showboat’s customers after the closure, very likely because of the marketing plan employed.

Conclusion[24]

Because CEOC was insolvent at the time of the Showboat closure, the Examiner concluded that CEOC was not adequately compensated related to the transition of Showboat customers to Harrah’s Atlantic City (a CERP property) and a viable claim existed. The Examiner believed that CEOC should have been compensated to the extent CERP realized an incremental benefit relative to customers’ historical preferences (in part because of the movement of VIP hosts). While a certain creditor group estimated the value of this claim between $331 million to $384 million, the Examiner estimated the claim between $3.0 million and $7.0 million based the present value of the net cash flows associated with the incremental Theo revenue.

This article was previously published in Insights: Alvarez and Marsal, May 21, 2018, and is reprinted here with permissions.

[1] https://cases.primeclerk.com/ceoc/Home-DownloadPDF?id1=MzM3Mzgx&id2=0

[2] The bankruptcy code allows for the appointment of an examiner who shall perform an investigation of the acts, conduct, assets and financial condition of the debtor, and other duties as ordered by the court.

[3] Examiner’s Report at pp. 78–80.

[4] The Financial Times’s blog, FT Alphaville, describes the Examiner’s report: “For anyone who has followed the machinations at Caesars, the blow-by-blow accounts behind all the deals makes for an incredible read—the first 100 or so pages of executive summary has plenty of dirt. And even if you have not, just reading the lengths private equity firms will go to salvage bad investments is mind-blowing.” (https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2016/04/11/2158973/liquidity-v-solvency-caesars-edition/)

[5] Examiner’s Report at pp. 728–729.

[6] Stars identify the locations of the CEC properties.

[7] Examiner’s Report at pp. 712–716.

[8] Examiner’s Report at pp. 726–733.

[9] Examiner’s Report at p. 716.

[10] Examiner’s Report at p. 712.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Examiner’s Report at p. 740.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Examiner’s Report at p. 724.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Examiner’s Report at p. 733.

[17] Examiner’s Report at pp. 733–734.

[18] Examiner’s Report at pp. 740–745.

[19] Examiner’s Report at p. 748.

[20] “Theo” or “Theoretical Win” is a “[m]athematical equation used to estimate how much [Caesars] theoretically believe[s] the casino will win from a customer based on probability.” Theo represents the expected house advantage from gaming activity.

[21] Examiner’s Report at pp. 45–748.

[22] See Part 1: Caesars’ “Liquidity and Solvency”. https://www.alvarezandmarsal.com/insights/part-1-caesars-liquidity-and-solvency

[23] “Cross-Play” is the amount of play generated from customers crossing over from one Caesars property to another.

[24] Examiner’s Report at pp. 752–756.

The authors are Laureen Ryan and Michael Shanahan.