Money Laundering

In More Ways Than One

It seems every few months we read about a financial institution involved in a money laundering scandal. The bank typically agrees to pay a fine, promises to behave, hires consultants to monitor and report to the regulators, and the scandal is generally forgotten. You may ask what do the consultants do and what do they monitor? This article will discuss the development of two recent scandals that made noteworthy headlines, the redflags to be watchful for, and the safeguards deployed to understand, monitor, and control the risks.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]Resources:

Using Financial Forensics in the Defense of White-Collar Crimes

[/su_pullquote]

It seems every few months we read about a financial institution involved in a money laundering scandal. The bank typically agrees to pay a fine, promises to behave, hires consultants to monitor and report to the regulators, and the scandal is generally forgotten.

You may ask what do the consultants do and what do they monitor? This article will discuss the development of two recent scandals that made noteworthy headlines, the redflags to be watchful for, and the safeguards deployed to understand, monitor, and control the risks.

The most recent example is of Danske Bank, founded in 1871 in Copenhagen, Denmark. Apparently, the Estonian branch of Danske was involved between 2007 and 2015 in the flow of $230 billion of illicit money from Russia across Europe and the rest of the world. The bank is saying it still does not know whose billions moved through its remote branch over nearly a decade. The CEO has resigned, the stock has lost more than half of its value, and the reputation of more than a hundred years left in tatters because of alleged willful neglect. [1]

We have seen similar cases where BNP Paribas was fined by the U.S. regulators to the tune of nine billion dollars. Among others charged and fined were HSBC, ING, and almost all the large U.S.-based banks. This rise in scandals has its roots in the globalization of finance, and most importantly, a push in the political environment to make the banks more responsible for policing the criminal and terror-related money flows. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund estimate that global fraud and money laundering constitutes about three to five percent of the world’s gross domestic product, or between $2.2 and $3.6 trillion a year.

Before 9/11, laws and regulations inherently focused on the drug trade and the illegal profits seeping back into the economy. The focus shifted after 9/11 to include terrorism financing, which was also traced to money laundering.

What is Money Laundering?

Money laundering is essentially the processing of assets generated from a criminal activity to obscure the link between the funds and their illegal origins. Anti-money laundering (AML) refers to the controls that require a financial institution to deter, prevent, detect, and report money laundering activities. The methods by which money may be laundered are varied and can range in sophistication. AML controls that have been implemented by statute include requirements that financial institutions file or report suspicious activity (i.e., Suspicious Activity Reports [SAR] and or Currency Transaction Reports [CTRs]). FinCEN (the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network of the U.S. Treasury) also encourages voluntary filing related to any potential money laundering or terrorist activity.

Any organization that receives or disburses funds, whether by cash, checks, wires, or other types of bank transfers, is susceptible to elements of fraud, corruption, and money laundering. The source could be both internal and external, both domestic and international, and the regulatory impact could be both from receiving or disbursing funds. If the funds received have origins in a tainted source, it will have a reputational impact that will affect the financial institution and its stakeholders.

Some of the types of methods used to “launder” funds include:

If funds are disbursed to a known criminal enterprise, not only may it adversely impact the financial institution, but it may also subject the principals to criminal charges. Banks charged with crimes may be subjected to both civil and criminal penalties.

Watch Out for These Red Flags

Some red flags that may indicate a potential problem related to fraud, corruption or money laundering and result in a reputational risk, as well as expose a financial institution to civil and criminal charges, have origins in these types of transactions:

- Commissions and/or fees greater than the industry norm, especially outside of the U.S.

- Unnecessary or unusual middlemen.

- ”Special” invoices or invoices with no discernible service being provided.

- Contributions received from or given to individuals or organizations with suspect background or credentials.

- Excessive travel and entertainment expenses.

- Unusual donations and/or expenses, especially related to sources outside of the U.S.

- Fee payments or monies transmitted and subsequent request of refunds for the same.

- Excessive wires and/or money transactions with countries identified for heightened risk for bribery; such as Russia, China, Brazil, Mexico, and India.

- Lack of review of any transactions from embargoed entities, countries, or jurisdictions.

- Willful blindness, which generally results in a potential liability.

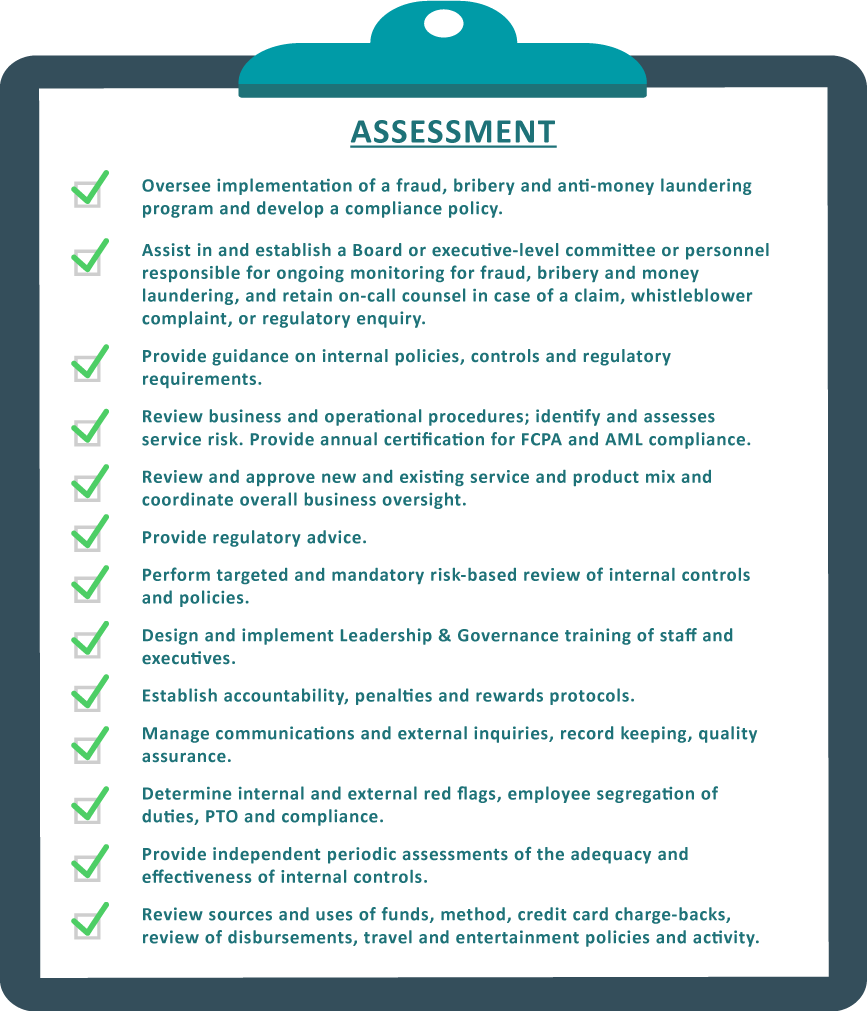

Marcum LLP has established a robust program to assist financial institutions in meeting their respective AML responsibilities. This program includes conducting risk assessments of financial institutions to create, implement, and monitor a plan of internal controls and compliance to deter, monitor, and detect fraud and money laundering. The actual assessment/plan is tailored to the financial institution’s size, number of employees, types of activity, funding sources, disbursements, and vulnerability to fraud and money laundering. An assessment could include the elements above for review, discussion, and organizational impact.

Ali Ansari is a director in the Advisory Services Division. He has over 25 years of experience in forensic accounting and has worked extensively in litigation consulting and advisory services for clients with revenues ranging from the thousands to the multi-millions. He has directed multiple engagements in all facets of fraud investigations, contract disputes, risks and risk management, internal controls, internal audit, regulatory consulting, AML look-backs and FCPA investigations, asset and expense tracing, due diligence, white-collar crime investigations, whistleblower cases, and economic damage analysis.

He is an accomplished speaker in risk management, internal audit, and forensic accounting to various professional groups and a former guest lecturer at Florida Atlantic University. He has conducted internal audit training for financial institutions and conducts courses in the areas of ethics, internal audit, litigation consulting, and other subjects for CLE credits at various law firms. He is a former president of TiE Florida and former board member of the Florida ACFE chapter. He is well versed in IT systems, including creating proprietary models as part of testimony in various litigation cases as an expert witness, as well as process flows in creating, developing, and executing risk management systems and initiatives, within the U.S. and other parts of the world.

Ali Ansari can be contacted at (954) 320-8158 or by e-mail to M.ali.Ansari@marcumllp.com.

[1] While this article was being researched, SwedBank, another financial institution in Sweden is currently embroiled in alleged misdeeds of suspicious transfers exceeding $100 billion. Its CEO was fired and the share price plunged by a third since the case first erupted on February 20, 2019.