Private Capital Markets: The Major Themes

There’s Lots We Know about Private Capital. There are Things We Don’t Know, too—and Need to Be Aware of.

Robert T. Slee explains in this excerpt several key macro insights—and related themes—that his recent book Private Capital Markets is based on. The macro insights are that corporate finance theory doesn’t predict behavior in private capital markets, and valuation, capitalization, and transfer are not discrete and unrelated areas. Themes include insights on the differences between public and private markets, compliance, relative value, and more.Â

Much of the thinking behind the book Private Capital Markets is based on several macro insights. First, corporate finance theory does not predict behavior in private capital markets. Principles of corporate finance are not particularly useful to private managers. Second, people who view valuation, capitalization, and transfer as discrete and unrelated areas do not grasp the larger picture and are likely to make incorrect financing and investment decisions.

Finally, the private capital body of knowledge is large and expanding. Its full practice is effectively limited to those who dedicate themselves to its study. A number of important themes form the basis for a fuller description of private capital markets and middle market finance theory.

Theme One: Public and private capital markets are not substitutes for each other because they rely on different capital markets theories to explain market behavior.

Until now, private companies have been viewed in the literature as the unruly stepchildren of public markets. A select few of these children will occasionally come of age and be allowed to eat at the public or grown-up table; however, most are not considered mature enough to converse with. Private markets rely on a unique body of knowledge to explain its structure and activities. In other words, unique markets require unique market theories.

In the foreword of the book, finance professor John Paglia describes his personal journey from believing corporate finance explained the behavior in all capital markets to his current understanding that  middle  market  finance  better  explains  behavior  in the  middle  market. Professor Paglia, like all finance Ph.D.s, is a product of a system that officially recognizes only corporate finance as the theory that describes behavior in capital markets. Because the two market theories share a common lineage, there are bound to be similarities. However, public and private capital markets are based on differing motives of the participants and maturity of market mechanisms and other factors.

Many underlying assumptions between corporate and middle market finance are different and often severely at odds with each other. Several characteristics are particularly noteworthy:Â

- A market establishes value for public companies, whereas private companies must rely on a point-in-time appraisal or a transaction to determine value.

- Public companies have ready access to capital, but private companies must create capital solutions one deal at a time, with little certainty of success.

- There are differences in ownership risk, return expectations, anticipated holding periods, and extent of owner participation between the two markets.Â

These and other mechanistic differences between corporate finance and middle market finance point to the need for a separate financial theory for the private middle market. This is called middle market finance theory.

Theme Two: Motives of private business owners initiate actions, but operate under rules imposed by various authorities.

Nothing happens in the private capital markets until an owner decides to act. Motives of private owners initiate action. Motives drive appraisal purpose, or choice of value world, because a private owner should not undertake a capitalization or transfer without knowing the value of her business. Motives also decide the best capital structure for a firm. Further, an owner’s motive for a transfer leads to the choice of a transfer method, which yields a particular value. But motives alone do not dictate a final result. Authorities in the market must support the motive and provide it with additional momentum. No positive outcome is possible without this additional support. Authorities control both access and the rules of the game within their spheres of influence.

Who or what are these authorities? They are the traffic cops in the private markets. In valuation, for example, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), courts, laws, investors, lenders, and other agents are in position to make the rules. Capital authorities provide money. Transfer authorities range from laws, like the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) or estate laws, to financial intermediaries. Owners who ignore authority do so at their own risk. Authority sanctions its decisions by veto power or denying access to the market. For example, the IRS is not always correct in its decisions, but the full power of the U.S. government still stands behind it.

Who or what are these authorities? They are the traffic cops in the private markets. In valuation, for example, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), courts, laws, investors, lenders, and other agents are in position to make the rules. Capital authorities provide money. Transfer authorities range from laws, like the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) or estate laws, to financial intermediaries. Owners who ignore authority do so at their own risk. Authority sanctions its decisions by veto power or denying access to the market. For example, the IRS is not always correct in its decisions, but the full power of the U.S. government still stands behind it.

Private owners need to understand the mutually exclusive features and functions of private capital markets. Once the motive initiates action, specific possibilities are opened and closed. By launching the initial motive without proper information, the owner unknowingly chooses a course of action that narrows future options. This is further indication that knowing the rules of the game in advance is critical for success.

Theme Three: A private business value is relative to the value world in which it is viewed. These worlds offer a range of possible values.

A private business’s value is extremely dynamic; it changes based on the financial fundamentals of the company, but also on the reason for the appraisal. This is a startling observation. It suggests that every private business interest at a moment in time has a large range of correct values. The examples throughout the book show that PrivateCo is worth seven times more in the highest-value world as compared to the lowest-value world. Does this value relativity concept mirror reality?

Yes, every private business interest embodies an array of possible values. Proof of this statement is empirically evident. For instance, a private minority interest may have substantial fair value, a modicum of fair market value, and almost no market value. It seems strange to many observers that the same business interest at the same time can be correctly appraised as a host of different values. Yet, due to a proliferation of appraisal purposes and functions, value, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder.

Valuation is the language of private capital markets, but it would seem the players speak different dialects. With all of these peculiar perspectives on value, how does business actually get transacted? Â In other words, how do parties ever agree on the value of a private business interest?

The grimaced, chiseled faces of veteran intermediaries answer this question: agreement occurs only when the parties either transact in a neutral world, such as market value, or the party with the greater pull forces the other participant to play in their world. This is what happens in the world of owner value every day. Typically, no deal is possible with owner-managers unless you play by their rules, or they get desperate and transact in a world other than their authoritarian stronghold.

Theme Four: The Pepperdine Private Capital Market Line (PPCML) describes risk and return in the middle market by showing how credit is rationed based on the provider’s credit quality requirements.

Balancing risk and return is a key meta-financial concept in any market. Market players will not invest unless they have a method to measure and manage risk. This is a major problem in the private markets. Because information is opaque, no liquid or even semiliquid market is possible. But, in the effort to get paid for taking risk, savvy investors have some useful tools at their disposal.

The primary tool is the credit box. Capital providers ration funds based on credit quality established in the credit box. Money is not lent or invested unless a prospect meets the requirements.  The  second tool is  the  portfolio,  or  more  precisely,  the  ability to  manage  a portfolio effectively. All successful capital providers are adept at monitoring and managing their portfolios. Providers prune nonperforming investments from the portfolio and attempt to extend successful positions. Ultimately, the combination of a well-positioned credit box and sound portfolio management techniques enables capital providers to meet their return expectations.Â

The PPCML captures, on an empirical basis, the private return expectations of private institutional capital providers.  This line provides a risk/return capital road map to private markets, specifically the middle market. This is in contrast with much of the current literature that does not indicate a return difference in choosing venture capital over bank debt, for example. One book even promotes the use of private equity capital over bank debt because “it is better to have partners than put up with a bank’s constant demands.” While this may be true, it ignores the fact that private equity is probably three to five times more expensive than bank financing.

Theme Five: Business transfer comprises a spectrum of alternatives. Owners select a transfer channel and method based on their motives or goals.

Owners have dozens of alternatives to use in transferring their business. In most cases, a transfer can be engineered once an owner determines her goals. It turns out that choosing a goal is often the hardest part of the transfer process.

Many owners procrastinate before making the transfer decision. A somewhat exaggerated example involves an 85-year-old man who sought my firm’s help to effect a transfer. The man was distraught because “Junior” had recently been offered the chance to buy the family business, but had declined the opportunity. The elderly owner castigated the younger generation for their flimsy work ethic and lack of vision. I later discovered that Junior was 62 years old! Junior told me he had worked in the business for more than 30 years and had offered to buy the business more than 10 years before, but the “old man” wouldn’t even discuss it. The most revealing aspect to this story is that it recurs every day on Main Street. One can only wonder why.

The answer is based more in psychology than finance. Successful owner-managers are a different breed. They tend to want to control things. Their lives become so intertwined with the business that planning the transfer of their business is like planning the transfer of their existence. I refer to this phenomenon as “walking to the elephant graveyard.” Many owners prefer to be carried out of their office in a box than face this walk. Even the elderly owner mentioned above did not really want to transfer his business to Junior or anyone else. It turns out he had a terminal disease and was motivated to control the transfer, just like he had controlled everything else in the business for more than 50 years.

Private Capital Markets

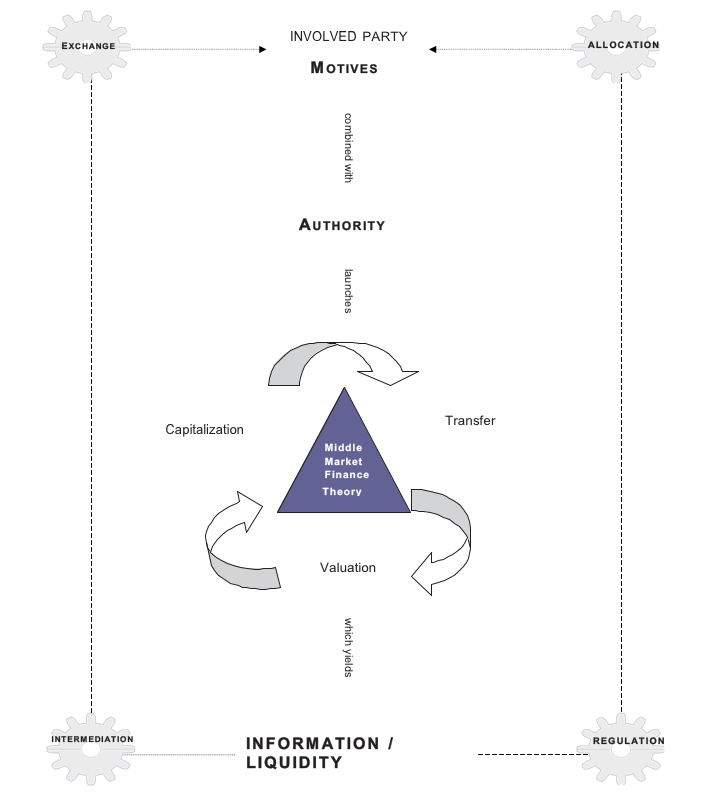

These broad themes provide a framework that describes the private capital markets. Exhibit 1 is a graphical depiction of this market structure. Although private capital markets are unique, their boundary is more like a membrane than a brick wall. This permeable membrane enables participants to meet their primary goal: to get information and money into and out of private capital markets. Various market mechanisms provide the gears, or movement to the markets. In a sense, private markets are held together by exchange, allocation, intermediation, and regulation. Exchange provides the trading activity between the parties. Allocation provides the resources necessary to feed the market. Intermediation facilitates market transactions. Finally, regulation provides the market rules.

Exhibit 1: Structure of the Private Capital MarketsÂ

The motives of an involved party lead to action in the markets. But millions of non-owners also inhabit private markets. Examples of involved non-owners are management teams, capital providers, lawyers, CPAs, and so on. For this schematic to be effective, it must work for all parties. For example, a banker or investor’s motives are subject to the same market forces as any other involved party.

The relevant authority tempers motives. This is fortunate or capitalism would soon run amuck. The wild West economic environment of modern-day Russia is an example of what happens when motives go unrestrained. However, there are things to consider within the concept of authority. There are competing authorities throughout the market. For example, the IRS and tax courts compete on a variety of valuation issues. In this case, the authority with the stronger logical argument generally carries the day.

Further, there are outside authorities that parachute edicts into the private markets. The Financial Accounting Standards Board mandated fair value onto private markets, even though this board was actually attempting to solve a public company issue. Finally, authorities control only their sphere of influence. Sometimes this is fairly limited, as in the case of investors whose only sanctioning power is to not invest. In other cases, the authority’s sphere is quite broad, such as the IRS. The influence of authority is felt in valuation, capitalization, and transfer issues.

Positive activity begins when authority is combined with motive; at this step an involved party’s motive is empowered. This combination launches middle market finance theory. This theory is the rotary engine of the private capital markets. Valuation, capital structure formation, and business transfer are interconnected to power the markets. Triangulation refers to the use of two sides of the middle market finance theory triangle to help fully understand a point on the third side. The three-legged stool analogy seems to effectively capture this image.

Due to the lack of a trading market, private business appraisal is a difficult exercise. Much of the current literature suggests that fair market value is the default standard of value (value world). This has caused thousands of appraisers to rely on this single standard regardless of the reason for the appraisal. For instance, appraisers routinely determine open market values of business interests using fair market value. This leads to an overvaluation of minority interests and an undervaluation of control values.

Value world theory predicts that every private company embodies a wide range of values. Many observers are uncomfortable with this thought, presumably because it disrupts their “every- business-has-one-true-value” mentality. Many people also believe that public markets provide the necessary information to derive private value conclusions. However, we now know that private valuation is holistic and not driven by public capital markets.

Describing  capital  structure  formation  is  less problematic  than  valuation  since  this  source material is less theoretically driven. Several simple observations describe private capital: private companies need capital; institutional capital providers have it; somehow parties occasionally negotiate a deal. Credit boxes, sample terms, and expected rates of returns explain this process. The analogy to a financial bazaar seems to best describe the actual workings of the private capital markets.Â

Business transfer is the most interconnected side of the private capital markets triangle. Transfer depends on the value world in which the transfer takes place and the availability of capital to make it happen. After more than 15 years providing private financial engineering services to the middle market, I’m still amazed when a transfer deal actually closes. Everything seems to be against it. Only the will of the parties can overcome the obstacles. This is why both parties need to be somewhat equally motivated once the letter of intent is executed.

Although the gears and arrows on Exhibit 1 suggest market movement, the schematic can’t capture the velocity of the private capital markets. No diagram can. Ultimately, private markets yield two precious commodities: information and liquidity. Information in private markets is like water in the desert. It’s both necessary and scarce. Those who master it usually win the game. It’s just that easy. Successful managers effectively gather, manage, and deploy information. Unsuccessful managers wonder why they’re a step slow and never seem get a break.

To the victor goes liquidity. If information is the water, liquidity is the oasis. It’s extremely difficult to get money into and out of private markets. Once again, well-conceived strategies enable this to happen. But strategies take time and require a certain single-mindedness. Nearly all owners possess these attributes; only some owners convert these qualities into liquidity.

What We Do Not Know

A separate book is possible on what we do not know about private capital markets. So as not to outweigh the broad themes, only five particularly fertile research areas are discussed here.Â

1. What factors motivate people to own and manage private businesses? Perhaps only one percent of the population should own a business. Yet many more than this make the attempt. Why? What motivates people to seek the 24/7 lifestyle that comes with the owner-manager title? Certainly control of one’s destiny is important to this group. For many, the risks associated with ownership outweigh likely returns. This might be another instance where the lack of good information causes people to understate risk and overstate return. A better understanding of the motivating factors of business ownership will lead to a better understanding of how owners make important decisions.

2. What needs to occur to have efficient private capital markets? Private capital markets are inefficient, at least when compared to public markets. Without an active trading market for private securities, it seems unlikely private markets will ever be liquid, which is a precursor to efficiency. Each market mechanism would need to change for efficiency to occur. As a start, the quality and quantity of information needs to dramatically improve. Regulation from the government might have to mandate this change. The mode of exchange needs to become more liquid. Intermediation needs to become more market-maker oriented and less reliant on outside agents.

Market efficiency matters. Increased efficiency enables companies to maximize their resources. Perhaps the private markets will never be efficient, but further study of this issue might help make them more efficient than they are today.

3. Why don’t more business owners create value in their businesses? The author believes that the majority of business owners are not increasing the value of their businesses. This lack of value creation has created a substantial “value gap” in the private markets. The value gap represents the difference between what an owner thinks or wants his or her business to be worth versus what the market of investors thinks it is worth. The value gap is the result of long periods where companies have not generated returns on investment greater than their cost of capital. This alarming opinion was reached partly because most business owners do not even know what it means to increase the value of their firms. Owners and managers have not been educated on the framework described in this book. Why not? Private companies generate the majority of the U.S. gross domestic product. What are we waiting for?

3 ½. Why are expected and realized returns so dramatically different?  Every institutional private capital provider expects to achieve an all-in rate that is much higher than the return actually realized. For instance, Private Equity Groups (PEGs) expect to receive 25-30%, but as a group, receive less than 10%. Venture capitalists structure their deals using a 35-40% return expectation, yet receive about the same return as PEGs. This is an incredibly inefficient use of capital. What are we to make of this? Is this underperformance due to the difficulty of picking winners in private capital markets? Or are the institutional capital providers not adding enough value to their investments? Eventually this imbalance will cause sources of capital to find other intermediaries with new models that generate higher realized returns.

3 ¾. Does private cost of capital affect the lower-middle market’s ability to compete against larger domestic companies and globally? Private companies have a much higher cost of capital than large public firms. The lack of liquidity in private markets only partially explains the difference. Information opacity is a further cause of private inefficiency that directly leads to higher return expectations for private capital providers. Does a higher cost of capital necessarily put private firms at a competitive disadvantage? There is some empirical evidence that it does. For  example,  factoring,  which  is  the  most  expensive  capital  type,  has  historically  been extensively used by textile and furniture manufacturers. This capital structure causes these manufacturers to have extremely high costs of capital. I believe this cost structure prohibited the textile and furniture trades from reinvesting in their businesses, especially in production- enhancing technologies. Of course, these industries wilted under the onslaught of global competition.

It seems reasonable to believe that, all things being equal, a higher cost of capital limits the value-creating investment choices of a firm. Since the U.S. government is counting on small businesses as the job engine for the foreseeable future, this is an extremely important consideration.

4. How do owners use options to determine transfer alternatives? Many owners avoid making the transfer decision to avoid walking to the elephant graveyard. Yet, some owners do plan their exits. How do they make this decision? Do they internalize the business transfer spectrum and choose the option that best fits their motives? This seems somewhat unlikely to me. I have assisted in hundreds of private transfers. I have found that it is difficult to get owners to concentrate on sophisticated planning options. It is just not where they live.

It has always been an American dream for parents to transfer the family business to their kids. Something is amiss in America, however. Twenty years ago perhaps 30% of private businesses transferred from one generation to the next. Now the number is likely closer to 10%. Why? Has something changed in the family unit to cause this low transfer percentage?

Will educating business owners as to the dozens of transfer options available enhance their desire to plan the exit? There is no way to be certain, but this must be preferable to just selling out when it is no longer fun owning the company.

5. Why don’t our institutions support the private capital markets? First, where are the academics? I speak on dozens of college campuses each year in America. Only rarely do I find a single traditional academic who knows anything about private capital markets, let alone the middle market. I constantly ask these academics: “Would you consider anyone who knows only half of their field of study to be an expert?” Of course, they answer “No.” Then I point out that private markets generate more than 50% of the U.S. economy and that private markets are unique in behavior and almost totally separate from large public markets. What do I hear? Silence.

We can’t expect our students to become successful owners and operators of private companies when they are not introduced to even the most basic concepts in school. If academics will not engage the private capital markets body of knowledge, they need to admit that they are not experts in their fields, and just get out of the way of those of us who are.

Further, why does public policy largely ignore the private capital markets? To this end, why does government policy either ignore or is just plain detrimental to private markets? It is strongly in the United States’ best interest to help grow private markets, as the vast majority of jobs are created there. Politicians constantly proclaim that small businesses are the engines of the economy, yet they then pass law-after-law that effectively pours sand into the gas tanks of private businesses? Why?

A Final Thought

I believe private capital markets are the last major uncharted capital frontier. Private Capital Markets is a conceptual Lewis and Clark-type survey. I hope others heed the call and expand our understanding of the terrain. This trailblazing adventure reminds me, in some ways, of the 19th Century rush to California. Upon seeing the Sierra Nevada mountains for the first time, the starry-eyed younger prospectors would whisper, “There’s gold in them thar hills.” The grizzled veteran miners would nod approvingly, then add a critical insight: “Eet’s there all right…but only for them that know where to look.”

Robert T. Slee, CBA, CM&AA, is President of Robertson & Foley, an investment banking firm that provides valuation, capital raising, and transfer advisory services to middle market companies. He speaks extensively on value creation for private businesses.

This article has been adapted from Chapter 36 of Private Capital Markets: Valuation, Capitalization,  and  Transfer  of  Private  Business  Interests,  2nd  Edition,  Robert  T.  Slee, Copyright (c) 2011 Robert T. Slee. Reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

This article was originally published in the Third Quarter 2011 issue of Business Appraisal Practice.