Part II: Dual-Purpose 409A Valuations: Here’s Why and How They Overvalue Stock Options

The Winklevoss Twins Realized Too Late the Value They’d Agreed to for Their Common Shares of Facebook. Here’s How it Played Out.

Last week Lorenzo Carver introduced the topic of how 409A valuations destroy value for some shareholders. Today’s piece is a case study in how a wide disparity in value estimates largely created by the 409A process played out in the UConnect v. Facebook lawsuit.

Last week I introduced the topic of how 409A valuations destroy value for some shareholders. Today’s piece is a case study in how a wide disparity in value estimates largely created by the 409A process played out in the UConnect v. Facebook lawsuit. Next week, in conclusion, I’ll offer thoughts on the causes of today’s status quo and suggestions on how the industry can avoid these sorts of problems going forward.

Example of Value Destruction: ConnectU v. Facebook

The ConnectU v. Facebook lawsuit serves as an example of how dual-purpose 409A valuations destroy value for employees at venture backed companies.

Every five to 10 years, one or two investments come along that reinforce the potential capital appreciation promised by the VC industry. Without these companies, the investment class might not exist, and the need to create complex structures for these companies would cease to exist. Examples of these rare companies that offset the many losses, and thereby create competitive aggregate returns for the VC industry, include Google, Microsoft, Netscape, Amazon, eBay, and Genzyme. However, none of those companies were subject to 409A valuation requirements for employee stock options, since 409A was enacted as part of the of the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004 in response to Enron—but did not become effective for venture-capital-backed companies like Facebook until January 2008.

Today thousands of 409A valuations are performed for venture-backed and angel-funded companies to determine the value of common stock and, therefore, the strike prices for options granted to employees at these companies. Ironically, the Facebook 409A-related lawsuit offers a glimpse into how, even at one of the most successful venture-capital backed companies ever, failure to understand different standards of value, combined with low volatility inputs and dual-purpose valuations, can destroy value.

Anyone who has seen the Oscar-winning movie about Facebook, “The Social Network,” is aware that the Winklevoss twins sued Facebook and its founder Mark Zuckerberg claiming that Zuckerberg stole the idea for Facebook from their company, ConnectU. The movie notes that the pair won a settlement of $65 million ($45 million in Facebook common stock and $20 million in cash).

![]() What is not in the movie, but is central to the importance of independent valuations of high-growth private companies, is that the same plaintiffs sued Facebook and Zuckerberg again after the original settlement was reached to get access to a 409A valuation of Facebook’s common stock prepared by Houlihan, Lokey, Howard & Zukin as of January 2008. Why would they want the 409A valuation report?

What is not in the movie, but is central to the importance of independent valuations of high-growth private companies, is that the same plaintiffs sued Facebook and Zuckerberg again after the original settlement was reached to get access to a 409A valuation of Facebook’s common stock prepared by Houlihan, Lokey, Howard & Zukin as of January 2008. Why would they want the 409A valuation report?

The Winklevoss twins realized (too late) that the price at which they agreed to value their common shares was higher than the “fair value” and “fair market value” for those shares. Ironically, they didn’t really need a 409A valuation report to tell them this—they could have applied basic math and reached that same conclusion in minutes. However, they did not realize their error until after the original settlement was concluded.

Valuation professionals all know that 409A valuations overstate the fair market value of the common stock, but understate the “enterprise value” of the company. Despite this reality, unless the 409A valuation is done immediately prior to an IPO, the value of the common stock concluded in the report will almost always be less than the value of the preferred stock. So in the case of the Winklevoss twins, a lower price per share would have meant a bigger ownership interest (more shares) in Facebook as part of the settlement.

The chain of events before and after the second Winklevoss suit is helpful in understanding the many ways that the term “value” is used in the context of venture-backed companies like Facebook, and also the costs of not fully understanding the context.

TIMELINE

September 2004: Litigation started with Facebook being sued by Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss and Divya Narendra for, basically, stealing the Facebook idea from ConnectU.

This lawsuit was filed about four months after Peter Thiel (founder of PayPal) invested $500,000 for around “10 percent of the company [Facebook],” according to press reports. Using VC parlance, this would imply a pre-money value of $5,000,000 ($500,000 ÷ 10%), which of course is not the same as enterprise value or fair market value to a financial buyer.

April 2007: IRS issues final regulations for Section 409A, which among other things effectively require venture-funded companies to have third-party appraisals done in order to earn a safe harbor from potential penalties associated with mispriced options.

October 2007: Microsoft invests $240 million in Facebook for 1.6 percent of the company. According to press reports, this is $240MM ÷ 1.6% = a $15 billion pre-money value in VC parlance (or a 3,000X increase from the “valuation” Peter Thiel bought in at just three years earlier).

November 2007: Hong Kong billionaire Li Ka-shing invests $60 million in Facebook for the same Series D shares Microsoft received.

January 2008: 409A regulations become effective.

June 2008: Facebook settles with ConnectU founders for $65 million, calculated (approximately) as follows: $20 million in cash + $45 million in common stock = $65 million.

August 2008: Press reports Facebook plans to allow employees to sell some of their shares at “internal” (409A) valuation of around $4 billion. This valuation, unlike the preceding pre-money values noted, would be based on Revenue Ruling 59-60 definition of fair market value and, therefore, on the related definition of a hypothetical buyer and seller.

As you can see, the 409A total equity value for Facebook, as reported by the press, was nearly 75 percent less than the valuation produced under the value standard used by actual VC investors, the pre-money value.

May 2009: DST invests $200 million in Facebook at a reported “valuation” of $10 billion.

July 2009: TechCrunch blogger Michael Arrington reports that DST will offer employees $14.77 per share for their common stock, and they have 20 days to accept the offer. Note, at $14.77 per share, this amount is still less than half of what Microsoft paid for its preferred shares and, as a result, less than half of the common stock value the Winklevoss team agreed to accept one year earlier as part of their settlement.

Now consider the volatility of an asset that, by one standard, has increased in value by 3,000X in just three years, as Facebook did in the timeline. If you use the volatility from Yahoo!, Baidu, and Google, what are the chances that their respective publicly traded shares saw swings in value of 3,000X?

This speaks to the issue of the standards of value used by VCs, which might be considered investment or portfolio value based on what a business might become, versus the standard used in 409A valuations, which assume a financial buyer acquiring an interest in a business as it sits today. Although it can be difficult to reconcile the total company or total equity values of these different standards (pre-money/post money value versus fair market value as defined in Revenue Ruling 59-60), the expected volatility under both standards should be the same for three main reasons:

- Both standards of value require the use of a waterfall and breakpoints to allocate value and the required returns.

- VC investors invest only in founders and management teams committed to aggressively pursuing penetration of markets that are expected to grow rapidly. This mandate for large, as opposed to incremental, outcomes is the same regardless of what standard of value is applied, and increases the range of potential outcomes.

- Most investors recognize that the higher the required return, the higher the risk. Most valuation professionals realize that higher risk means a higher variability of returns, which means that returns are more volatile.

- The post-money value of Facebook following Microsoft’s investment, around $37.60 per share, which is very close to the $15 billion pre-money valuation reported by the press.

- The $8.8 value per share cited by plaintiffs as a “recent valuation” price while arguing for access to Facebook’s 409A valuations.

- 409A valuation price per share cited by the Appellees Facebook, Inc. and Mark Zuckerberg as being publicly disclosed on the California Division of Corporations website, apparently based on a valuation done prior to the Microsoft Series D investment.

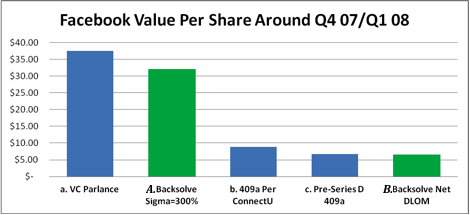

Exhibit 2: Facebook Value per Share around Q4 2007 / Q1 2008

The press, attorneys for both sides, and even parties familiar with venture capital and valuation found it challenging to reconcile the large chasm between the $15 billion dollar enterprise value reported in the press and the $3 billion to $5 billion enterprise values they felt were implied by the 409A reports filed with the State of California and reported elsewhere. Nearly every 409A valuation for a venture-funded company poses similar reconciliation issues, albeit not always such a large difference. The green bars in Exhibit 2 are price-per-share values derived using back-solve calculations.

These green bars demonstrate how using a company-specific volatility input, as opposed to using much lower volatility inputs from publicly traded companies, can bridge most of this gap in many cases. Item A (capital A) in Exhibit 2 is a back-solved enterprise price per share obtained using a volatility input of 300 percent. The green bar labeled item B (capital B) in Exhibit 2 illustrates the price per share after applying a DLOM, arrived at using 300 percent as the volatility input. Notice how the higher volatility input results in an indicated (back-solved) enterprise value that is very close to the pre-money value per share calculated by the VCs (a higher enterprise value than implied by the 409A valuations). Using the same higher volatility input, 300 percent, also results in a lower net value per share for the common stock (item B in Exhibit 2), resulting in a lower exercise price for employee stock option grants .

This may seem like an extreme example, especially since when the press the reported an “internal valuation” value in the $3 billion to $5 billion range, they didn’t consider the DLOM. The same holds for the legal filings by both sides, which make no specific mention of the marketability discount.

The same three Black-Scholes required inputs—volatility, risk free rate, and term—that were applied to get an indicated marketability discount can be applied to the publicly disclosed 409A or “internal” common stock values to make those figures more usable in comparing the indicated enterprise values extrapolated by the press. For expediency, we’ll use the risk free rate (4.37 percent), term (5.1 years) and volatility (34 percent) Google reported in an annual report for the period ended December 31, 2007. Each of those inputs (risk-free rate of 4.37 and term of 5.1 years) are the same as those used for my protective put, except that this volatility was nearly 9X higher than the volatility input Google used to price its options, and probably 5X higher than the volatility used in most 409A valuations.

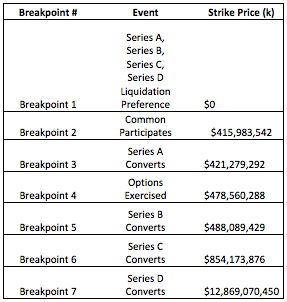

The resulting DLOM would be around 18 percent, suggesting that Facebook’s reported 409A value per share before the discount would have been around $10.72 per share. But in order for the Facebook common stock to get $0.01 in proceeds, the company would have to sell at a price that, at a minimum, provided Microsoft and other Series D investors with the original $37.60 they paid (their “liquidation preference”). That minimum sale price, not including transaction fees, would be around $415,000,000, the first breakpoint as illustrated in Exhibit 3. This table demonstrates why the use of waterfalls and breakpoints are essential for understanding the implications of both the VC pre-money approach and a 59-60-compliant fair market value appraisal. It illustrates the approximate breakpoints for Facebook’s outstanding securities around the first quarter of 2008, along with how each of those breakpoints would become a call strike price if the OPM were used to allocate value to the various classes of securities.

Exhibit 3: Approximate Breakpoints for Facebook’s Capital Structure

around Q4 2007 / Q1 2008

Exhibit 3 illustrates that the degree to which a breakpoint is higher than the enterprise value (or out of the money), a lower proportion of the enterprise value will be allocated to it. However, the higher the volatility input, the greater the probability (in a Black-Scholes/risk-neutral world) that the strike price will be breached and, therefore, the more enterprise value that will be allocated to that breakpoint.

Given these facts, even if the 409A valuation expert’s conclusions were widely off the mark, the expert would still conclude that if Microsoft paid $35.90 to $37.60 per share for its preferred stock, and someone received common stock a few months later, the common stock would probably not be worth more than 50 percent of what Microsoft paid for its preferred stock, unless an IPO were imminent.

If this is happening to the value of employee stock options of venture-funded companies, why isn’t anyone up in arms about it? The answer relates in part to who is paying the price for overvalued employee stock options today.

Lorenzo Carver, MS, MBA, CPA, CVA, is founder and CEO of Liquid Scenarios (www.LiquidScenarios.com) in Boulder, CO. He invented the Carver Import Algorithm and Search2Model, and holds a patent on VC valuation technology. Carver is the author of Venture Capital Valuation (John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, 2011) and programmed the award-winning small business valuation software, BallPark Business Valuation (1999).