409A Options Valuations: Who Pays the Price and What We Can Do

UConnect v. Facebook Showed How 409A Valuations Can Destroy Value. Here’s What Shareholders and VCs Need to Know—and Some Ideas About How to Better the Situation.

Lorenzo Carver previously explained how 409A valuations destroy value for shareholders receiving grants, and provided a case study of how this all played out in UConnect v. Facebook. In this final article in a three-part series, Carver presents us with thoughts on who pays the price when a valuation is overvalued, what some of the causes of today’s status quo are and some specific suggestions on practices our industry might adopt to fix the situation.

I introduced this series by discussing how 409A valuations destroy value for shareholders receiving grants and in the second article in the series offered a case study on how this sort of conflict played out very specifically in UConnect v. Facebook.   This article concludes with thoughts on who pays the price when a valuation is overvalued, what some of the causes of today’s status quo are, and some specific suggestions on practices our industry might adopt to fix the situation.

Who Pays the Price for Overvalued Options?

Although we began this discussion with respect to employee stock options, all equity securities in venture-backed companies are essentially call options on an exit opportunity, as opposed to rights to future earnings per share. If you can definitively identify differences in rights to cash from a liquidity event and differences in optionality for each venture-backed security, then increased realized and unrealized gains can be achieved. The Facebook/ConnectU example is just one of thousands of similar real-world cases. In each of these cases different parties inside and outside these venture-funded companies pay the price or realize additional profits because of someone’s lack of understanding concerning valuing venture-backed-company securities.

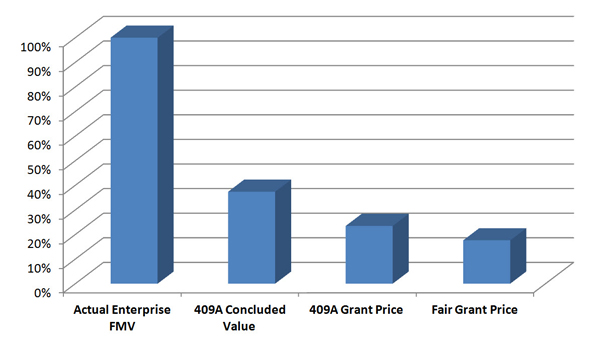

Exhibit 4: 409A Valuations Overvalue Options and Undervalue Companies

(Source: Liquid Scenarios, Inc.)

Many venture capital investing partners would say it’s obvious that 409A valuations understate a company’s true value. This is because of the popular VC valuation parlance referred to earlier, “pre-money value,” which simply multiplies the most recent price per share paid for a series of preferred stock by the maximum number of shares that could hypothetically be outstanding as of the date of that financing transaction.

Some would say the 409A valuation really doesn’t matter, and therefore the prices at which the company is issuing its options don’t really matter either, within reason. However, few would note that these differences between the true fair market value of employee stock options, based on reasonable volatility inputs, have an impact on every investing partner’s cash-on-cash return and, therefore, impact everyone in a transaction. But that is the case. Every investing partner’s cash-on-cash return is impacted by how fairly employee options are priced. Exhibit 4 clearly demonstrates this.

If this is correct, who is making money as a result of overvalued employee stock options, and who is losing money as a result?

Losers

The biggest losers will be key employees whose options are granted at a higher strike price than is truly fair. At this writing, most employees can’t determine if the strike prices for their options are fair.

Who’s the second-biggest loser from a cash flow perspective? Ironically, it’s the same organization that set the rules for 409A, the U.S. Department of Treasury. If options are being granted at a higher price than what is “fair,” then when a company does realize a successful exit, all things being equal, the gain realized by employees on those options will be lower than if a fair price had been used. As a result, the Treasury actually ends up getting lower receipts.

Winners

Who benefits from overpriced employee stock options? As the waterfall we presented earlier illustrates, employee stock options compete with other security classes for exit proceeds, to the extent that those options are in the money. If the exercise price is higher than what is fair, that means holders of preferred stock, such as VCs, are entitled to a higher proportion of proceeds than would otherwise be the case if the options were granted lower values.

VCs do not want get extra rights to cash from a liquidity event in this manner, do not tend to pay particular attention to option grant prices until the company is about to exit, and would certainly prefer that the employees they depend on to develop high-growth ventures are compensated fairly with respect to stock-based incentives. So if default winners of extra exit proceeds due to overpriced employee stock options would prefer to have fairly priced options, who is responsible for consistently increasing the grant prices and thereby decreasing the intrinsic value of these securities for so many employees?

The auditors.

Do Auditors Drive Valuators to Overvalue Options?

Few if any of the parties that are most responsible for shaping how venture backed common stock fair market value calculations are performed for tax purposes are tax professionals. Indeed, they aren’t even the investing partners that comprise the primary market participants putting real cash on the line in transactions that drive changes in common stock fair market value for VC-funded companies. The investing VCs may decide, or more accurately “recommend,” who performs the 409A valuations for their portfolio companies, but their sole objective in doing so is helping their investees, partners on boards, employees, and prospective future acquirers avoid the substantial penalties for being “grossly negligent” in performing those valuations. Instead, the parties that have had the most influence on the common stock value conclusions are the financial statement auditors.

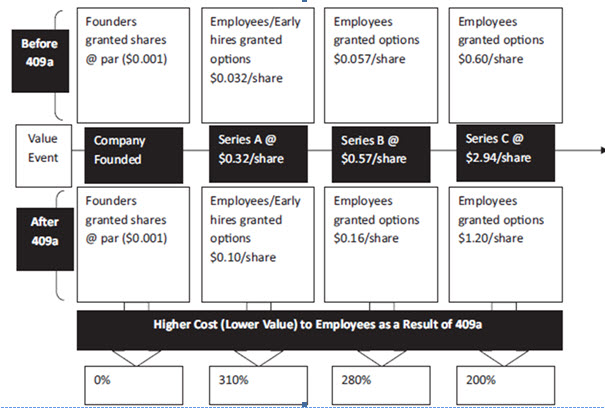

The accounting rules for employee options, or stock-based compensation, require a standard of value that you can’t really get to without either (a) observing a true market transaction or (b) coming up with an estimate of the market value and then applying some adjustments. Unfortunately for employees of the venture-backed companies, the parties that have paid most heavily for this reality are illustrated in Exhibit 5.

Exhibit 5: Options Undervalued before 409A and Overvalued after 409A

(Source: Liquid Scenarios, Inc.)

All their [auditors’] decisions seem to revolve around which method or approach produces the highest number or value indication, not which way is the most logical method in light of the company’s stage and what they’re going through as a startup. So all of us appraisers have to be careful about the auditor reactions, which results in a lot of our decisions erring on the high-side. –Jeff Faust, AVA, 409A valuation expert and director of business valuation at Berger Lewis

A highly successful entrepreneur and angel investor told me, “I don’t see why we can’t just use 10 percent of the preferred price like we used to do. No one believes the 409A reports, almost no one even reads them, and hardly anyone understands them.” The term “fair value” has sometimes been defined, in part, as an unbiased and rational estimate of the potential market price. Simply applying 10 percent to the last round of financing (the “10 percent rule” employed by most venture-backed company boards when pricing employees options at the early stages for many years before auditors and valuation professionals became heavily involved as a result of 409A) would certainly meet the test of being unbiased and, in many cases, also being rational. If a preferred financing event had occurred within a reasonable period, the boards would simply multiply that round’s deemed issue price by 10 percent, or some comparable fraction (5 percent, 20 percent, etc.). The resulting product would be the price at which options were granted and this was the estimated fair market value of the common stock.Â

While the more rigid analysis taking place for early-stage companies in response to 409A may also be generating “rational and unbiased” conclusions, those conclusions may not be fair to employees, who should be considered the “willing” buyers or “willing” sellers in these transactions.

Unfortunately, those same “buyers” and “sellers” clearly do not have access to one of the requirements for “fair value” used in the standard of value that applies to venture-fund transactions: “having a reasonable understanding about the asset or liability and the transaction based on all available information, including information that might be obtained through due diligence efforts….”Â

Employees at venture-backed companies who receive options are not shareholders until their stock options are vested and exercised. As an optionee, as opposed to a shareholder, any rights to information would be incorporated in the company’s employee option plan. A lot of times employee rights in the option plan simply state that optionees have rights to access a copy of the plan and rights to access their stock option documents. If rights to a valuation report exist, that would most likely be in the fine print. And even then, the optionees would probably not pay much attention to it. From a practical standpoint, the 409A valuation is considered highly confidential, so if a company can avoid disclosing it to employees who are not executives, that would increase the chances of keeping the report confidential. –Craig Lilly, corporate and securities attorney, Greenberg Traurig

If a venture capital general partner told the limited partners in the fund that they were paying 300 percent more for every investment in every portfolio company, across the board, in response to a tax regulation and auditor recommendations, what do you think the LPs of that venture fund would do? Their dissatisfaction with that strategy would probably be reflected in immediate attempts to sell their LP interests at a heavy discount to avoid future obligations (capital calls) to fund that investment approach.

One of the reasons why you don’t see venture-funded company employees objecting to paying 300 percent more across the board for rights to purchase the same amount of shares is a lack of understanding concerning what they are receiving and how its “valuation” takes away from their earning potential. With the probability of a “grand slam” rather small, few employees are going to bicker, they just assume their cash compensation is comparable to their peers at other VC-backed, and non-venture-backed, companies. So the differences between one exercise price and another may not appear meaningful to them.

Much of the current lack of understanding is perpetuated by financial industry jargon and accounting pronouncements that are difficult for the auditors themselves to recite accurately without a copy of the rules close by. In this regard, being generally confused by the redundant and inconsistent use of the word “value,” the employees are not alone. Venture fund GPs, investing professionals, limited partner investment managers, and even the accounting firms that sign off on reports used by beneficiaries of these sophisticated parties share that confusion.

Call to Action

An approach similar to that used to build up a discount rate for non-venture backed company valuations must be used to build up a volatility input for VC-funded company valuations, due to the sensitivity of value conclusions for these companies to volatility. It may be difficult to accomplish this to the full extent needed until valuations for financial reporting purposes, which are the domain of auditors, are considered distinct from or subordinate to valuations for determining fair market value according to Revenue Ruling 59-60. These steps can restore the usability of both (a) the financial statement disclosures investors rely on when venture -backed companies go public or get acquired, and (b) the fairness of securities issued to employees that are generally unlikely to have “a reasonable understanding about the asset…based on all available information.”

Focusing on next financing rounds as an input for time and the range of likely changes in the underlying asset values would better align 409A value conclusions with market participant realities. Most importantly, perhaps, some of the brightest and most hardworking young people in our country will end up with fairly priced equity compensation incentives in exchange for their efforts to build the next Google or Facebook.

Asking that every valuation review explicitly support modeling the next round of venture funding, as opposed to the current practice of focusing on some specific future exit scenario date, may be too much to ask auditors to do quickly. On the other hand, by simply acknowledging the reality that volatility inputs obtained from public companies are routinely far too low to be comparable to those experienced by venture-backed companies is easy to do. If an audit team or valuation specialist group at a Big Four auditor saw that a venture-backed company with zero to $15 million in revenue was primarily valued using the same weighted average cost of capital as IBM in a DCF model, what do you supposed would happen to the appraiser responsible for that? When auditors propose that public company comps be used solely to arrive at a volatility input, as opposed to building the volatility input up, the outcome is the same: value destruction. It is time for a change.

Lorenzo Carver, MS, MBA, CPA, CVA, is founder and CEO of Liquid Scenarios (www.LiquidScenarios.com) in Boulder, CO. He invented the Carver Import Algorithm and Search2Model, and holds a patent on VC valuation technology. Carver is the author of Venture Capital Valuation (John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, 2011), and programmed the award-winning small business valuation software, BallPark Business Valuation (1999).