How to Estimate the DLOM for Controlling Ownership Interests

Willamette Management Author Explains: What You Need to Know About DLOMs

Aaron Rotkowski explains why it’s appropriate to apply a DLOM to a controlling ownership interest—and how to figure it—and why it doesn’t make sense to rely on restricted stock studies and pre-IPO studies to estimate the DLOM for that interest. Find out more.

The discount for lack of marketability (DLOM) is the subject of many articles and studies, but there is a dearth of literature relating to the application of a DLOM to a controlling ownership interest in a closely held company.

There are at least two reasons why the DLOM for controlling ownership interests is not widely covered: (1) the discounts are typically much smaller than the DLOM for minority, or non-controlling, ownership interests (and, therefore, have less of an impact on the valuation, all other factors being equal), and (2) analysts value non-controlling ownership interests more frequently than they value controlling ownership interests.

Because of the lack of coverage this topic receives, many valuation analysts are not properly trained to select an appropriate DLOM for a controlling ownership interest. In my experience, valuation analysts will sometimes use unsupported or erroneous methods to support the DLOM for a controlling ownership interest.Â

For example, valuation analysts sometimes rely on data presented in restricted stock studies and pre-initial public offering (“pre-IPO”) studies to estimate the DLOM for a controlling ownership interest. This may lead to a selected DLOM that is too large.

Conversely, valuation analysts sometimes ignore the DLOM altogether when valuing a controlling ownership interest in a closely held company. This may lead to a selected DLOM that is too small.

This article will address the two common errors valuation analysts make when valuing a controlling ownership interest in a closely held company. Specifically, this article will explain why it is typically (1) appropriate to apply a DLOM to a controlling ownership interest and (2) inappropriate to rely on restricted stock studies and pre-IPO studies to estimate the DLOM for a controlling ownership interest. The last section of this article will present one methodology valuation analysts can follow to estimate the DLOM for a controlling ownership interest in a company.

Controlling Ownership Interests v. Non-controlling Ownership Interests

Owners of controlling interests are free to sell their shares to a willing buyer. The owner simply needs to find a buyer and negotiate the transaction terms. A non-controlling owner, on the other hand, typically faces severe and oppressive restrictions that affect his ability to transfer the subject non-controlling ownership interest.

The issue facing the controlling owner is therefore a matter of liquidity. That is, the owner is free to sell his shares, but there is no readily available market into which to sell his shares. This is an advantage over the non-controlling owner, who is faced with problems of liquidity and marketability. Not only does a non-controlling owner lack a market or organized exchange to sell his shares, he is typically restricted from selling his shares by agreement or otherwise. Many valuation analysts will therefore refer to the DLOM for a controlling ownership interest as a discount for lack of liquidity.

Using correct nomenclature is important. However, for ease of understanding, this article will not distinguish between “DLOM” and “discount for lack of liquidity” as they apply to controlling ownership interests. This article will refer to the discount as a DLOM.

Error #1: Ignoring the DLOM When Valuing a Controlling Ownership Interest

In a valuation context, the DLOM, “measures the difference in the expected price between (1) a liquid asset (that is, the benchmark price measure) and (2) an otherwise comparable illiquid asset (that is, the valuation subject).”

Actively traded public company stock is an example of a liquid asset. It takes approximately three days to receive cash from the sale of an actively traded public company stock. This three-day marketing period (or holding period) is often cited as the benchmark for marketability.

The owner of a controlling ownership interest in a private company has the ability to sell his ownership interest, but he does not enjoy the same market that the owner of public company stock enjoys. The most significant difference between the marketability of actively traded public company stock and a controlling interest in a closely held company is the time it takes to convert the asset to cash.

Many textbooks, articles, and courts have argued/accepted that holding period and value are inversely related. That is, as the investor’s expected holding period increases, the value of the underlying asset decreases.

Based on the fact that (1) investors value marketability and (2) studies show that closely held companies take around six months to eighteen months to sell (compared to three days for actively traded public company stock), the application of a DLOM to a controlling interest in a closely held company is often appropriate.

Although it is widely accepted that it is appropriate to apply a DLOM in the valuation of a controlling ownership interest, there is not a consensus amongst practitioners.Â

According to Financial Valuation—Applications and Models:Â

There has been an ongoing debate as to whether a discount for lack of marketability should be applied or even considered when valuing a controlling interest. The opponents of marketability discounts are fairly consistent in their arguments that the lack of marketability is included in the pricing of the controlling interest.

Proponents of discounts believe some discount should be made over and above the discount rate or price multiple based upon the valuation method employed.

And, according to Z. Christopher Mercer, “My basic question remains: How can an appraiser discount a controlling interest in a business for lack of marketability when the owner(s) maintain control of the cash flows (which determine the value to begin with) while s/he or they wait?” To paraphrase Mercer, the cash flow that accrues to the 100% owner of a closely held company during the company’s marketing period will mitigate any DLOM that would be appropriate. The point Mercer makes is theoretically valid, but does not apply equally to all companies.

It seems intuitive that two assets—one that can be sold in a day and one that takes six months to sell—would have different values. However, to Mercer’s point, the difference in value between the two assets may be small if the owner enjoys (1) benefits (monetary or otherwise) during the holding/marketing period, and/or (2) no increase in sale price risk related to the holding/marketing period. These two characteristics do not affect all closely held companies the same way.

To address Mercer’s point, let’s consider a seller that owns his or her home. If (1) the seller lives in the home, (2) there is no opportunity cost to receiving the sale proceeds in months rather than days and (3) the expected sale price is approximately the same today as it would be in several months, then the lack of marketability could be very small.

Consider the opposite scenario. Let’s consider a seller that (1) owns a home that he derives little utility from (e.g., a second home), (2) could invest the sale proceeds in another investment and earn a superior risk-adjusted rate of return, and (3) is selling his home in a declining real estate market. A six-month holding period under this scenario would clearly have a greater detrimental impact to value than in the scenario outlined in the preceding paragraph.

The home sale example is analogous to the value of a controlling interest in a closely held company. An example of a closely held company that would warrant a low discount—based on the factors discussed in the preceding paragraphs—is a highly profitable company that operates in a mature industry and is listed for sale during a strong economy. A closely held residential construction company listed for sale anytime during 2006 through 2008 is an example of the opposite facts and circumstances.

It is important that the valuation analyst (1) understands the unique, company-specific factors that would have an effect on the DLOM, and (2) does not apply the same discount in each and every assignment. Applying a 0% DLOM to every controlling ownership interest is just as inappropriate as applying a 35% DLOM to every non-controlling ownership interest.

Error #2: Relying on Restricted Stock Studies and Pre-IPO Studies to Estimate the DLOM

When Valuing a Controlling Ownership Interest

There are two distinct types of empirical studies that are used to estimate the DLOM: (1) empirical studies used to estimate the DLOM for non-controlling (or minority) ownership interests, and (2) empirical studies used to estimate the DLOM for controlling ownership interests.

Empirical studies used to estimate the DLOM for non-controlling ownership interests are based on data from transactions involving non-controlling ownership interests. These studies generally fall into two categories: (1) restricted stock studies and (2) pre-IPO studies.

Restricted stock studies compare the price difference between (1) registered shares of publicly traded companies (i.e., shares that can be freely traded in the open market), and (2) unregistered shares of publicly traded companies (i.e., shares that cannot be freely traded on the open market).

Pre-IPO studies are based on arm’s-length sale transactions in the stock of a closely held company that has subsequently achieved a successful initial public offering of its stock. In a pre- IPO study, the DLOM is quantified by analyzing (with various adjustments) the difference between (1) the public market price at which a stock was issued at the time of the IPO, and (2) the private-market price at which a stock was sold (in an arm’s-length transaction) prior to the IPO. In both the restricted stock studies and the pre-IPO studies, the transactions analyzed involve non-controlling ownership interests (except under certain limited circumstances). These studies are appropriately relied on to estimate the DLOM for non-controlling ownership interests.

On the other hand, the studies that are used to estimate the DLOM for controlling ownership interests are generally based on (1) the cost to sell the subject company, and (2) the inherent risks that accompany that sale.Â

The DLOM for controlling interests and the DLOM for non-controlling interests are separate and distinct concepts. It is not appropriate to use a discount study related to a non-controlling interest to estimate the DLOM for a controlling interest.Â

According to Business Valuation–Discounts and Premiums, using the discount studies in a way other than what was intended is a common failure of appraisers:Â

[Restricted stock studies and pre-IPO studies] help quantify discounts for lack of marketability for minority interests. However, starting with such data and somehow moving from there to a discount for lack of marketability for a controlling interest is an unacceptable leap of faith, not grounded in a logical connection. The rationale for discounts for lack of marketability for controlling  interests is different from the reasons for discounts for lack of marketability for minority interests.

And, according to CCH Business Valuation Guide:Â Â

There are two broad methods for developing marketability discounts for non-controlling interests in private companies (there is another set of studies dealing with controlling interests in private companies).One practical reason (and perhaps the most compelling reason of all) these studies are not applicable to controlling ownership interests is that the restricted stock studies and pre-IPO studies involve transactions in non-controlling ownership interests.

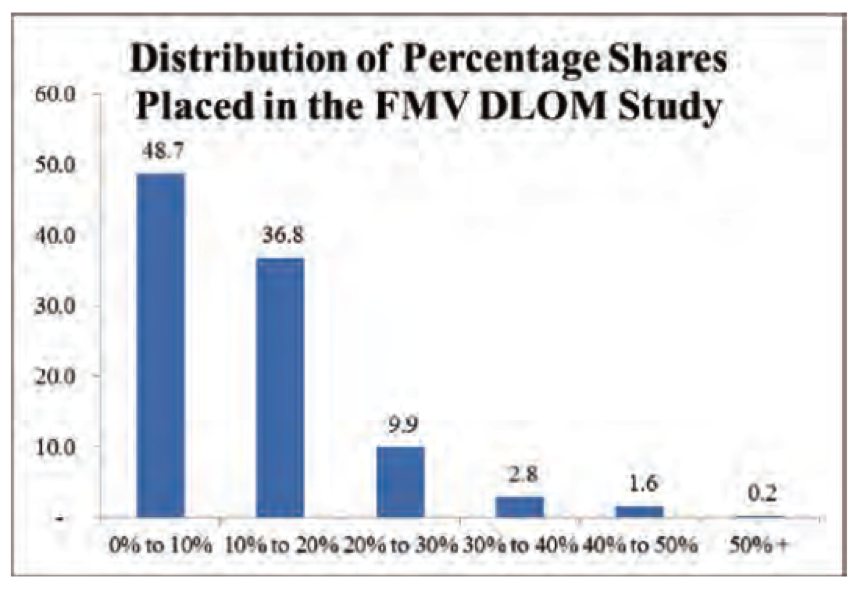

For example, FMV Opinions, Inc. examined 573 restricted stock transactions occurring after January 1, 1980. The FMV Opinions study is unique because study authors make certain underlying data from the study publicly available. Of the 573 restricted stock transactions analyzed by FMV Opinions, Inc., 85.5%t of the transactions in the FMV Opinions restricted stock study involved ownership interest of 20% or less. The distribution of the shares placed in the FMV Opinions study is presented in the chart below.

Only one out of 573 transactions in the FMV Opinions study involved an ownership interest greater than 50 percent. And, based on my firm’s review of that transaction, that transaction involved related parties and may not be indicative of fair market value. No transaction in the study was for 100 percent of a company’s equity.Â

Furthermore, my colleagues at Willamette Management Associates and I have reviewed the restricted stock studies and pre-IPO studies. Based on our review of these DLOM studies, the underlying transactions studied either (1) primarily involve non-controlling interests, or (2) do not disclose whether the interest transacted was a controlling ownership interest or non-controlling ownership interest. We found no evidence that a meaningful percentage of transactions involved a controlling ownership interest.

Because the underlying transactions in the restricted stock studies and pre-IPO studies involve non-controlling interests, it is appropriate to rely on the restricted stock studies and/or the pre-IPO studies to estimate the DLOM for a non-controlling ownership interest.

This sort of comparison is common in business valuation. Financial analysts will regularly use information provided by one company or transaction to make inferences about a company subject to analysis. That is the premise of the guideline publicly traded company method in the market approach to business valuation.

In the Guideline Publicly Traded Company Method, the more comparable the subject company is to the guideline (or comparable) company, the more meaningful the method is. Of course, no two companies are perfect for comparative purposes. If the differences between the guideline company and the company subject to analysis are too large, the comparison may not be meaningful.

In the same way that certain guideline companies in the Guideline Publicly Traded Company Method are not comparable to the company subject to analysis, certain DLOM studies do not apply to all subject interests. Â

For reasons discussed in a preceding section of this article, the differences from a marketability perspective between the two interests (i.e., a controlling ownership interest and a non-controlling ownership interest) are typically too large for this comparison to be meaningful. The most significant difference in marketability between controlling ownership interests and non-controlling ownership interests is that owners who enjoy the prerogatives of control are free to sell their ownership interest whereas non-controlling owners typically are not.Â

Relying on the correct discount study or studies is important because the studies conclude significantly different discounts. The consensus among valuation analysts is that DLOMs for controlling interests are significantly less than DLOMs for non-controlling interests.Â

Current Methodology Commonly Used to Estimate the DLOM for a Controlling

Ownership Interest

This article focuses on common errors in the application of a DLOM to a controlling ownership interest. A detailed presentation of the correct way to select a DLOM for a controlling ownership interest is outside the scope of this article. This section will briefly summarize (1) one common way valuation analysts estimate the DLOM for a controlling ownership interest, and (2) advantages and disadvantages of using that method to estimate the DLOM for a controlling ownership interest.

One of the more common ways analysts estimate the DLOM for a controlling ownership interest is to (1) estimate the costs to sell the subject company, and (2) calculate the costs as a percent of company value to conclude the DLOM.

According to Business Valuation and Taxes, the five factors must be analyzed in estimating discounts for lack of marketability for controlling interests are:Â

- Flotation costs (the costs of implementing an initial public offering)

- Professional and administrative costs, such as accounting, legal, appraisals, and management time necessary to prepare the company for a sale or IPO

- Risk of achieving estimated value

- Lack of ability to hypothecate (most banks will not consider loans based on private company stock as collateral, even controlling interests)

- Transaction costs (payments to an intermediary or internal costs incurred in finding and negotiating with a buyer).

The primary advantage to relying on these five factors to estimate the DLOM for a controlling ownership interest is that it has been accepted by various courts. A second advantage of this method is that it has been promulgated in books and articles. Third reason analysts rely on this method is that there is not compelling empirical support for an alternate method to estimate the DLOM for a controlling ownership interest.

However, relying on the cost to sell the subject company to estimate the DLOM for a controlling ownership interest has disadvantages. Valuation analysts that estimate a DLOM for a controlling ownership interest should also understand the disadvantages associated with relying costs to sell the subject company to estimate the DLOM for a controlling ownership interest.Â

First, the value of a company is typically thought to exclude transaction costs. Let’s assume that the invested capital of a business is worth $100 million, and transaction costs to sell the business are $5 million dollars. The value of that business is typically thought to equal $100 million, not $95 million. That is, there generally is no relationship between the value of a business (and, by extension, marketability) and the transaction costs to sell that business.

Second, marketability is typically defined as the difference in price an investor will pay for a liquid asset compared to the price he will pay for an illiquid asset. Based on this definition, the transaction costs to sell a controlling interest in an asset are not necessarily indicative of the difference an investor will pay for a liquid asset compared to the price he will pay for an illiquid asset.

Analysts should (1) consider the strengths and weaknesses of whatever method they rely on to estimate the DLOM for a controlling ownership interest, and (2) consider how company-specific factors will affect the DLOM (i.e., should the discount be on the high end of some indicated range or the low end of some indicated range).

Conclusion

There is no “perfect” method to estimate the DLOM for controlling ownership interests in closely held companies. In fact, the subject receives relatively little discussion relative to the DLOM for non-controlling ownership interests. In spite of this, there are two concepts related to selecting the appropriate DLOM for a controlling ownership interest that are widely accepted amongst valuation practitioners.

First, the DLOM for a controlling ownership interest is indeed usually appropriate. And second, it is not appropriate to rely on data presented in restricted stock studies and pre-IPO studies to estimate the DLOM for a controlling ownership interest. The financial analyst will produce more a credible and convincing valuation report if he or she is mindful of these two concepts when valuing a controlling ownership interest in a closely held company.

Moreover, the valuation analyst should specifically consider the specific facts and circumstances of the subject controlling interest when selecting a DLOM for a controlling ownership interest in a closely held company.

Aaron M. Rotkowski, CFA, ASA is manager at Willamette Management Associates. Aaron has over a decade of business valuation experience. His practice focuses on forensic analysis and dispute resolution, business and stock valuations, and valuations for other purposes. Aaron can be reached at (503) 243-7522 or at amrotkowski@willamette.com.