The Threshold of Commercial Reasonableness

A standard distinct from the fair market value standard

The fair market value is distinct from the commercial reasonableness standard. The article highlights how these standards are applied in a healthcare transaction and why it is important to distinguish these standards.

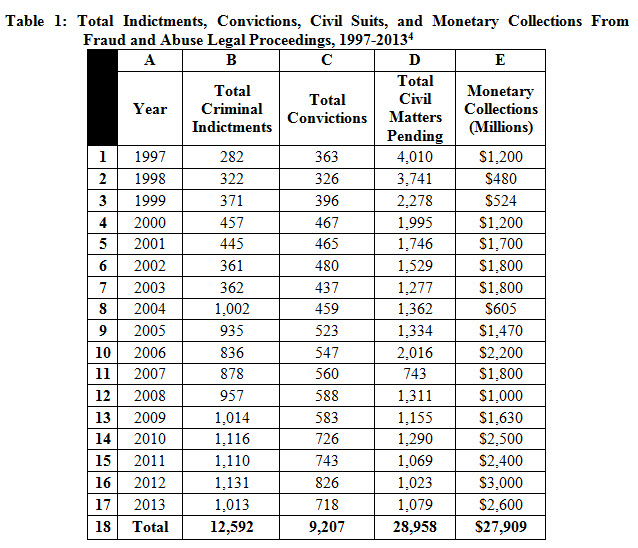

In response to the advent of accountable care and value-based reimbursement–which emerging reimbursement models rely on to achieve better outcomes at lower cost–hospitals are increasingly seeking closer relationships with physicians, including direct employment, co-management, and joint ventures.1 Corresponding with this growing trend toward hospital-physician alignment, there has been increased federal, state, and local regulatory oversight regarding the legal permissibility of these arrangements. Most notably, there has been more intense regulatory scrutiny related to the Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS) and the Stark Laws, especially as they relate to potential liability under the  False Claims Act (FCA).2 Both the Stark Laws and AKS require that any consideration paid to physicians not exceed fair market value (FMV) and be deemed commercially reasonable. 3

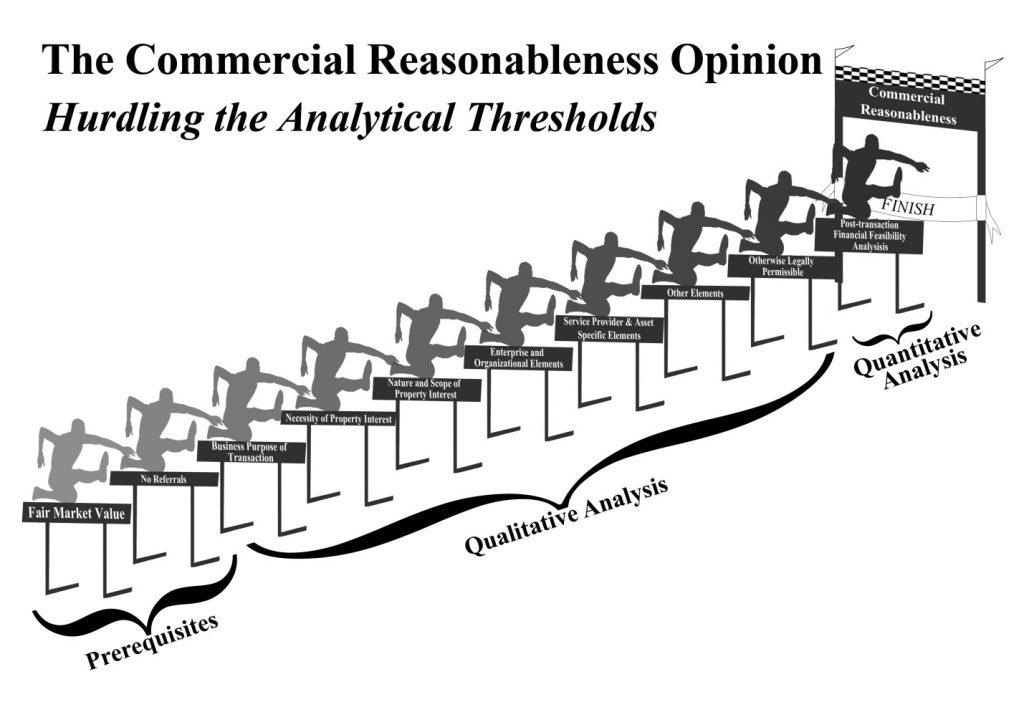

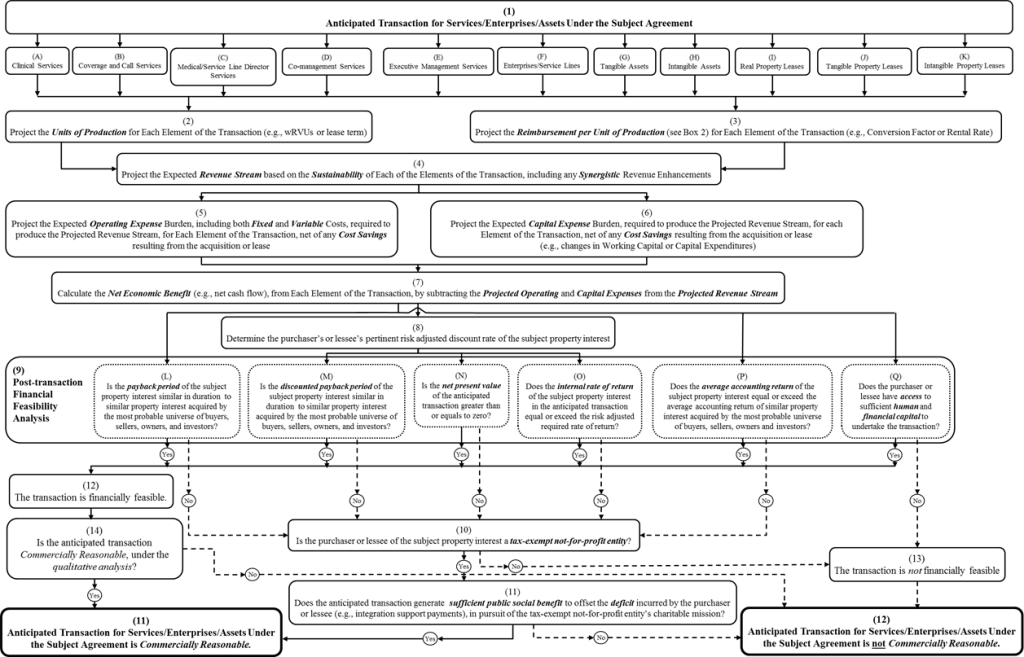

Valuation analysts should note that the fraud and abuse laws scrutinize many aspects of healthcare transactions, including physician compensation arrangements, under both the valuation standard of FMV and the separate, but related, threshold of âcommercial reasonablenessâ.5 While the analysis of the threshold of commercial reasonableness is separate and distinct from the development of a FMV analysis, requiring consideration of different aspects of the property interest included in the transaction, they are related thresholds and the consideration and analysis of one threshold does not preclude the analysis of the other threshold. For example, a necessary condition in order for an anticipated transaction to be commercially reasonable is that each element of that transaction must not exceed FMV. However, even in the event that each element of an anticipated transaction does not exceed FMV and meets that threshold, the anticipated transaction may still not be commercially reasonable, in that it does not meet the remaining analytical hurdles (see Exhibit 1). Note that a finding that an enterprise, asset or service meets the FMV threshold is not, in and of itself, sufficient to establish commercial reasonableness.6

A further distinction between a commercial reasonableness (CR) analysis and the development of a FMV opinion is that the commercial reasonableness thresholds include consideration of the ââŚvalue to the entity paying forâŚâ7 the enterprise, assets or services being transacted, while the FMV opinion requires that a universe of hypothetical buyers, sellers, owners and investors be considered. For example, consider the acquisition of ten linear accelerators by a purchaser. If the purchaser has need of only one linear accelerator, the purchase of ten linear accelerators even at a FMV price would not meet the necessity of the assets purchased threshold of the commercial reasonableness analysis.8

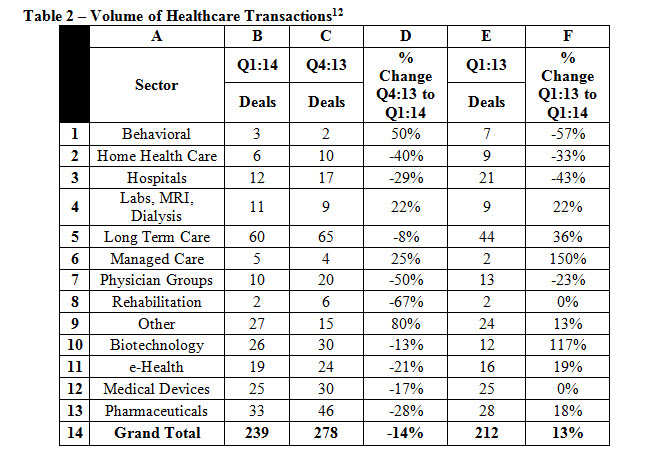

It is critical to obtain and maintain appropriate documentation that any given physician compensation arrangement (whether it be for clinical services, administrative services, on-call services, or a combination of services) meets both the standard of FMV and the commercial reasonableness threshold in order to withstand regulatory scrutiny. Typically, legal counsel does not provide opinions as to the commercial reasonableness of a compensation arrangement,9 and will most often retain and rely upon an independent valuation consultant to provide a certified valuation opinion that the arrangement does not exceed FMV and meets the requirements of commercial reasonableness. Due to the increase in healthcare transactions (see Table 2, below),10 opinions related to the threshold of commercial reasonableness of healthcare transactions are becoming an âincreasingly important service offered by healthcare valuation professionals.â11

Rendering a commercial reasonableness opinion requires that a specific set of core competencies be mastered by the valuation analyst apart from, but related to, the more traditional knowledge, skill set, and experience required in rendering FMV opinions related to the appraisal of the enterprises, assets and/or services being transacted. The key components of a CR analysis include both a consideration of the qualitative factors that affect the commercial reasonableness opinion, as well as a quantitative analysis of the elements of the anticipated transaction of the subject enterprise, asset or service.13

II Definitions of Commercial Reasonableness

While definitions of the commercial reasonableness threshold are significantly similar across the various federal agencies tasked with enforcing those regulations, there are subtle nuances between each agencyâs interpretation of the term âcommercial reasonableness.â The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has interpreted the term âcommercially reasonableâ to mean that an arrangement which appears to be ââŚa sensible, prudent business agreement, from the perspective of the particular parties involved, even in the absence of any potential referralsâ14 is commercially reasonable.

Additionally, HHSâs Stark II, Phase II commentary suggests that:

âAn arrangement will be considered âcommercially reasonableâ in the absence of referrals if the arrangement would make commercial sense if entered into by a reasonable entity of similar type and size and a reasonable physician of similar scope and specialty, even if there were no potential DHS [designated health services] referrals.â15

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and Office of the Inspector General (OIG) have also provided guidance in defining commercial reasonableness. IRS guidance regarding commercial reasonableness may be derived from IRS pronouncements on reasonable compensation, including:

- The 1993 Exempt Organizations IRS text titled âReasonable Compensation,â which states that âreasonable compensation isâŚthe amount that would ordinarily be paid for like services by like organizations in like circumstances;â16 [emphasis added]

- Chapter 2 of Publication 535, titled âBusiness Expenses,â which states ââŚreasonable pay is the amount that a similar business would pay for the same or similar services;â17 [emphasis added] and,

- Federal Regulations on âExcess Benefit Transactions,â which state, âreasonable compensation [is]âŚthe amount that would ordinarily be paid for like services by like enterprises (whether taxable or tax-exempt) under like circumstances.â18 [emphasis added]

It should be noted that no IRS pronouncement defining reasonable compensation specifically addresses the healthcare industry. However, the sources noted above may be useful in addressing commercial reasonableness thresholds in healthcare transactions.

Additionally, the OIG has defined a commercially reasonable transaction as one in which ââŚthe aggregate services contracted do not exceed those which are reasonably necessary to accomplish the commercially reasonable business purpose of the service.”19

III THE CR Analysis

The CR analysis is comprised of three component phases:

- Ensuring that certain prerequisites for the transaction;

- Developing a qualitative analysis of the transaction focusing on furthering the businessâs interest(s); and,

- Developing a quantitative analysis focusing on the transactionâs financial feasibility.

In the performance of each task, the analyst must determine if the transaction overcomes the various legal and analytical thresholds necessary to achieve a commercially reasonable result. See Exhibit 1: âCommercial Reasonableness Overview,â below, for a graphical illustration.20

III.A Transactional Prerequisites

The first task an analyst must complete in a CR analysis is to determine if the following two prerequisites are satisfied:

- All aspects of the transaction do not exceed FMV; and,

- The transaction is sensible in the absence of referrals.

III.A.1 Fair Market Value

In the healthcare setting, the FMV prerequisite requires that the consideration paid for all aspects of the transaction does not exceed FMV. The Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), now known as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), provided the following guidance for determining when payment for services and assets provided does not exceed FMV:

âWe intend to accept any method [for establishing FMV] that is commercially reasonable and provides us with evidence that the compensation is comparable to what is ordinarily paid for an item or service in the location at issue, by parties in arm’s-length transactions who are not in a position to refer to one another . . . . The amount of documentation that will be sufficient to confirm FMVâŚwill vary depending on the circumstances in any given case; that is, there is no rule of thumb that will suffice for all situations.â21 [emphasis added]

III.A.2 Sensible, Prudent Business Agreement in the Absence of Referrals

The second prerequisite that must be satisfied during a CR analysis is the determination of whether the anticipated transaction is ââŚa sensible, prudent business agreement, from the perspective of the particular parties involved, even in the absence of any potential referrals.â22 This requirement applies to the following situations:

- âRental of office space;â

- âRental of equipment;

- âBona fide employment relationships;â

- âPersonal service arrangements;â

- âPhysician incentive plans;â

- âPhysician recruitment;â

- âIsolated transactions, such as a one-time sale of property;â and,

- âCertain group practice arrangements.â23

The key aspect of this prerequisite is identifying the role of the physician referral in the transaction. In its interpretation of this prerequisite, the OIG looks for any financial arrangement which may induce a physician to change their referral pattern, such as:

- ââŚ[A]rrangements [to] promote overutilization andâŚunnecessarily lengthy stays;â24 and,

- ââŚ[P]ayments to induce physiciansâŚto reduce or limit services toâŚpatients.â25

III.B Qualitative Analysis

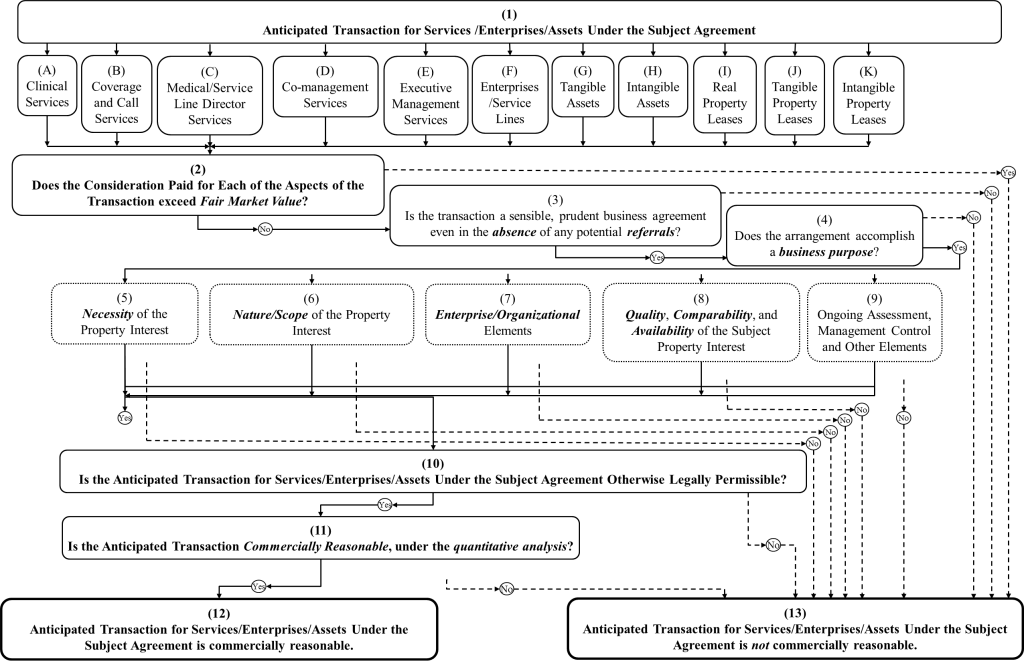

After insuring that the prospective transaction meets the prerequisites noted above, the second task an analyst must complete in a CR analysis is to perform a qualitative analysis of the elements of a proposed transaction. The thresholds involved in the qualitative assessment of commercial reasonableness focus on determining the acquirerâs business purpose(s) and how the anticipated transaction assists in meeting that purpose. The specific qualitative thresholds, as illustrated below in Exhibit 2: Qualitative Analysis for Commercial Reasonableness, are as follows:

- Business Purpose;

- Necessity of the Property Interest;

- Nature and Scope of the Property Interest;

- Enterprise and Organizational Elements;

- Quality, Comparability, and Availability of the Subject Property Interest;

- Management Control, Ongoing Assessment, and Other Elements; and,

- Otherwise Legally Permissible.26

III.B.1 Business Purpose

The first qualitative threshold the valuation analyst must analyze is whether the transaction fulfills a ââŚbusiness purposeâŚâ27 for the acquirer. This concept has been expounded upon by the OIG and the IRS as follows:

- HHS Commentary on the AKS Regulations considers transactions to have a business purpose if they can be âreasonably calculated to further the business of the lessee or acquirer;â28 and,

- The IRS defines business activities as those ââŚcarried on for the production of income from the sale of goods or the performance of services.â29

III.B.1.a Additional Business Purposes Beyond Net Economic Benefit

One element that may indicate a sensible, prudent business arrangement is the anticipated profitability resulting from the transaction. However, the net economic benefits generated from the invested capital may not be the sole business purpose of the anticipated transaction. Additional considerations include, but are not limited to:

- Expansion into new geographic areas;

- Expansion into new business lines;

- Augmenting existing service lines;

- Diversification benefits;

- Avoiding costs of establishing offices and facilities, management, and other resources, in place;

- Operating expense reductions;

- Increased asset utilization;

- Reduced cost of capital and greater access to capital;

- Horizontal integration;

- Vertical integration;

- Management and care protocols;

- Increased access to technology and innovation;

- Improved research and development; and,

- Tax motivation.30

These synergistic gains to a specific owner or investor, which would likely not be considered when performing a FMV analysis, may be significant in establishing that a transaction is commercially reasonable.31

III.B.1.b Not-for-Profit Entities

Additionally, tax-exempt, not-for-profit entities may, in the accomplishment of their charitable mission, provide non-monetary benefits to the âowners/investorsâ in the charitable organization, including taxpayers that act as the charitable benefactors to the not-for-profit organization. As such, it is likely that in furtherance of their charitable mission, tax-exempt, not-for-profit organizations may generate ongoing financial losses, which losses may be offset by the non-monetary economic benefits accruing to the community provided by the tax-exempt, not-for-profit organizations, such as increased public health awareness and vaccination efforts.32

III.B.2 Necessity of the Property Interest

The next threshold that must be overcome in performing a qualitative analysis is a determination as to whether ââŚthe items and services obtained⌠[are] necessary to achieve a legitimate business purpose of the [employer] (apart from obtaining referrals).â33 The IRS requires a determination whether the consideration paid for the property interest is âordinary,â34 (common and accepted in trade or businessâ)35 and ânecessary,â36 i.e., it is âhelpful and appropriate for the trade or businessâ37, in light of the âthe volume of business handledâ38 by the acquirer, e.g., the number of âbeds, admissions, or outpatient visits;â39 âthe complexities of the business;â40 and/or, the âsize of the organization.â41

Further guidance from the OIG commentary on the AKS suggests that analysts should determine how the âspace, equipment, or servicesâ meet the ââŚlessee or purchaser needs, intents to utilize, andâŚcommercially reasonable business objectives.â42

III.B.3 Nature and Scope of the Property Interest

Next, the analyst must make a determination as to whether the nature and scope of the property interest meet the needs of the acquirer. The IRS has provided guidance as to what would be considered a reasonable business expense for tax purposes, which may be used in determining whether the nature and scope of the assets and services included in the proposed transaction supports the necessity threshold, as discussed in III.B.2 above. The IRS guidance specifies that the analyst should determine whether the property interestâs cost is:

- A âcost of carrying on a trade or business;â43

- Undertaken âfor the production of income from the sale of goods or the performance of services;â44

- ââŚ[P]aid or incurred during the taxable yearâ;45

- ââŚ[R]easonable in terms of the responsibilities and activitiesâŚassumed under the contract;â46 and,

- ââŚ[R]easonable in relation to the total services received.â47

III.B.4 Enterprise and Organizational Elements

The IRS pronouncements on reasonable compensation for tax purposes require analysts to make a determination whether the consideration paid for the property interest is ââŚa sensible, prudent business agreementâŚâ for the acquirer. This determination is made within the context of:

- â[T]he pay compared with the gross and net income of the business;â49

- The âbusiness policy regarding pay for all employees;â50

- â[T]he cost of living in the locality,â51 based on an analysis of the ânational and local economic conditionsâ52 including whether the acquirer is located in a ââŚrural, urban, or suburbanâ53 area; and,

- The structure, size, and location of the purchaser.54

III.B.5 Quality, Comparability, and Availability of the Subject Property Interest

Based on the nature and scope of the services provided, the analyst should determine those attributes which speak to the quality, comparability, and availability of the services, assets, and enterprises included in the anticipated transaction. The IRS pronouncements on reasonable compensation for tax purposes advise analysts to consider âthe ability and achievements of the individual performing the service,â55 including âeducation,â56 âspecialized training and experience of theâ individual;57 âthe history of pay for the employee;â58 and, ââŚthe availability of similar services in the geographic area.â59 Additionally, the OIG advises that analysts consider ââŚthe skill level and experience reasonably necessary to perform the contracted services,â60 especially if ââŚthe services [could be obtained] from a non-referral source at a cheaper rate or under more favorable terms.â61 Finally, the Code of Federal Regulations specifies that analysts should consider âthe type, expected life, conditionâŚand market conditions in the areaâŚ[for] facilities or equipmentâŚ,â62 as well as whether âadequate alternative facilities or equipment that would serve the purpose are not or were not available at lower costs.â63

III.B.6 Management Control, Ongoing Assessment, and Other Elements

Other elements of the transaction which may not fit neatly into the above discussed categories include:

- The ââŚquality of management and interdisciplinary coordination.â64 The governmentâs expert witness report in the U.S. v. SCCI Hospital Houston Central case suggested that healthcare entities should conduct âa regular assessment of the actual duties performed by the [employee]…[and] it should be clear how effective the [employee] is doing his assigned job and if there is a bona fide need for continuing the services.â65

- In the U.S. v. Carlisle HMA, Inc., case, Judge Christopher Conner ruled healthcare entities need to determine whether the current âconsideration given and received [is paid] under materially different circumstancesâ66 rather than when the contract was entered.

- The OIG advises consultants to review transactions to determine if:

(a) âthe arrangements flow from an open, competitive request for proposal processâŚ;â

(b) âthe risk that the arrangements will result in an appropriate utilizationâŚ;â

(c) âthe arrangements areâŚlikely to have a negative effect on patient care;â and,

(d) âthe arrangementsâŚhave an adverse impact on competition.â67

III.B.7 Otherwise Legally Permissible

Compliance with other legal requirements is necessary for a healthcare transaction to be viable. Four federal legal regimes significantly influence healthcare transactions:

- Antitrust law;

- The Stark Law;

- The AKS; and,

- The Internal Revenue Code.

III.B.7.a Antitrust Considerations

One area of examination of legal permissibility for the anticipated transaction is the transactionâs influence on market competition, commonly known as antitrust law. Analysts should determine, based upon guidance on antitrust law from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), whether the transaction will likely result in any of the following:

- The transaction ââŚis likely to produce significant efficienciesâŚâ;68

- âThese efficiencies include the provision of services at a lower cost or the provision of services that would not have been provided absentâŚâ69 the transaction;

- The efficiencies achieved as a result of the transaction ââŚwill benefit consumersâ;70Â

- The transaction will help ââŚmonitor and control costsâŚwhile assuring quality of care;â71

- The transaction ââŚappears likely, on the balance, to be procompetitive or competitively neutral;â72 and,

- The transaction ââŚwould not increase the likelihood of the exercise of market powerâŚbecause of the existence of the post-[transaction] of strong competitorsâŚâ73

III.B.7.b Stark and Anti-Kickback Considerations

The commercial reasonableness threshold and the valuation standard of FMV factor into compliance with two statutory schemes: the Federal Physician Self-Referral Law, or âStark Law,â and the AKS. The Stark Law prohibits physicians from referring Medicare or Medicaid patients to an entity for DHS if the physician, or an immediate family member, has a financial relationship with that entity.74 However, 35 exceptions to the Stark Law currently exist, each of which falls into one of the following three categories:

- Exceptions that apply to both ownership/investment interests and compensation agreements;

- Exceptions that apply only to ownership/investment interests; and,

- Exceptions that apply only to compensation arrangements.75

The Federal AKS makes it a felony for any person to âknowingly and willfullyâ solicit or receive, or to offer or pay, any âremunerationâ, directly or indirectly, in exchange for the referral of a patient for a healthcare service paid for by a federal healthcare program.76 However, 25 statutory safe harbors exist within the AKS prohibitions.77 Generally, the exceptions to the Stark Law and the safe harbors for AKS require healthcare transactions to both be consistent with FMV and be commercially reasonable.78

III.B.7.c IRS Considerations

The IRS prohibits excess benefit transactions between tax-exempt organizations (such as a non-profit hospital) and other parties, in which âthe value of the economic benefit provided exceeds the value of the consideration received for providing the benefit.â79 However, Treasury Regulation 53.4958-6 creates a rebuttable presumption that the transaction is not an excess benefit transaction if certain requirements are met. Pursuant to these requirements, âpayments under a compensation arrangement are presumed to be reasonableâŚif:

- âThe compensation arrangementâŚ[is] approved in advance by an authorized body of the applicable tax-exempt organization composed entirely of individuals who do not have a conflict of interest with respect to the compensation arrangement;

- The authorized body obtained and relied upon appropriate data as to comparability prior to making its determination; and

- The authorized body adequately documented the basis for its determination concurrently with making that determination.â80 [emphasis added]

III.C Quantitative Analysis

In addition to the qualitative threshold of commercial reasonableness, valuation analysts should also undertake a quantitative analysis, as illustrated below in Exhibit 3: Quantitative Analysis for Commercial Reasonableness, as part of the determination of the commercial reasonableness of both the discrete elements and the entirety of the anticipated transaction. This post-transaction financial feasibility analysis should consider all forms of remuneration to be paid by acquirers to sellers and lessors. The elements of the post-transaction financial  feasibility analysis are not intended to be considered in isolation; rather, the analyst should consider both the individual merits of each property interest as well as the relationships between the property interests being acquired. While there are numerous techniques an analyst may use, four of the most prevalent techniques are:

- Payback period and discounted payback period;

- Net present value analysis;

- Internal rate of return; and,

- Average accounting rate of return.82

The analyst should consider the strengths as well as the weaknesses of the analytical techniques in selecting a particular method in performing the quantitative analysis.

The scope of this article does not allow for an in depth discussion of the merits of each analytical method noted above. Readers can visit the Heath Capital Consultants website for additional information or contact the authors of the article for additional guidance.

IV Conclusion

In this era of provider consolidation and more stringent regulatory enforcement, healthcare entities and providers should work closely, and in a timely manner, with competent healthcare legal counsel and certified valuation professionals to ensure that their compensation arrangements meet regulatory thresholds. When prepared by an independent certified valuation professional, and supported by adequate documentation, a certified opinion as to whether the proposed transaction does not exceed FMV and is commercially reasonable will significantly enhance the efforts of healthcare providers to establish a defensible position that their proposed transaction is in compliance.

Robert James Cimasi, MHA, ASA, FRICS, MCBA, CVA, CM&AA, serves as Chief Executive Officer of HEALTH CAPITAL CONSULTANTS (HCC), a nationally recognized healthcare financial and economic consulting firm headquartered in St. Louis, MO, serving clients in 49 states since 1993. Mr. Cimasi has over thirty years of experience in serving clients, with a professional focus on the financial and economic aspects of healthcare service sector entities including: valuation consulting and capital formation services; healthcare industry transactions including joint ventures, mergers, acquisitions, and divestitures; litigation support & expert testimony; and, certificate-of-need and other regulatory and policy planning consulting. Mr. Cimasi can be reached at (414) 994-7641 or at RCimasi@healthcapital.com.

Todd A. Zigrang, MBA, MHA, ASA, FACHE, is the President of HEALTH CAPITAL CONSULTANTS (HCC), where he focuses on the areas valuation and financial analysis for hospitals and other healthcare enterprises. Mr. Zigrang has significant physician integration and financial analysis experience, and has participated in the development of a physician-owned multi-specialty MSO and networks involving a wide range of specialties; physician-owned hospitals, as well as several limited liability companies for the purpose of acquiring acute care and specialty hospitals, ASCs and other ancillary facilities; participated in the evaluation and negotiation of managed care contracts, performed and assisted in the valuation of various healthcare entities and related litigation support engagements; created pro-forma financials; written business plans; conducted a range of industry research; completed due diligence practice analysis; overseen the selection process for vendors, contractors, and architects; and, worked on the arrangement of financing. Mr. Zigrand can be reached at (314) 994-7641 or at TZigrand@healthcapital.com.

Â

1“2014 Global Health Care Outlook: Shared Challenges, Shared Opportunities” By Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, 2014, p. 13; “The 5 C’s of 2013 Health Care” By Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, 2012, http://www.deloitte.com/assets/Dcom-UnitedStates/Local%20Assets/Documents/us_chs_MondayMemo_2013Healthcare_%205Cs_021313.pdf (Accessed 6/4/14); âCo-Management Arrangements: Common Issues with Development, Implementation and Valuationâ By Ann S. Brandt, et al, American Health Lawyers Association, May 2011, http://www.healthlawyers.org/Events/Programs/Materials/Documents/AM11/hutzler.pdf (Accessed 6/5/14); âTop 10 Factors to Consider When Exploring Joint Ventures as an Affiliation Strategyâ By Jonathan Spees, The Camden Group, June 2013, http://www.thecamdengroup.com/thought-leadership/top-ten/top-10-factors-to-consider-when-exploring-joint-ventures-as-an-affiliation-strategy/ (Accessed 6/5/14).

2“Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control Program: Annual Report for FY 1997” By The Department of Health and Human Services & The Department of Justice, To the United States Congress, Washington, DC, 1998; “Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control Program: Annual Report for FY 2007” By The Department of Health and Human Services & The Department of Justice, To the United States Congress, Washington, DC, 2008; “Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control Program: Annual Report for FY 2013” By The Department of Health and Human Services & The  Department of Justice, To the United States Congress, Washington, DC, 2014.

3âIllegal Remunerationsâ 42 U.S.C. 1320a-7b(b)(3)(B) (2012); âLimitations on Certain Physician Referralsâ 42 U.S.C. Section 1395nn(a)(1) (2012); âPersonal Services and Management Contractsâ 42 CFR Section 1001.952(d) (2007); âBona Fide Employment Relationshipsâ 42 USC Section 1395nn(e)(2) (2010); âAcademic Medical Centersâ 42 CFR Section 411.355(e)(ii)(B) (2010); âExceptions to the Referral Prohibition Related to Compensation Arrangementsâ 42 CFR Section 411.357 (2010); âFair Market Value: Analysis and Tools to Comply With Stark and Anti-kickback Rules,â By: Robert A. Wade, Esq. and Marcie Rose Levine, Esq Audio Conference, HCPro, Inc., (March 19, 2008), p.48.

4âHealth Care Fraud and Abuse Control Program Reportâ By Office of Inspector General, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2014, http://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/hcfac/index.asp (Accessed 6/5/14).

5âHealthcare Valuation: The Financial Appraisal of Enterprises, Assets, and Servicesâ By Robert James Cimasi, Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.,

2014, p. 938.

6âHealthcare Valuation: The Financial Appraisal of Enterprises, Assets, and Servicesâ By Robert James Cimasi, Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.,

2014, p. 937-938.

7âMedicare and State Health Care Programs: Fraud and Abuse: Clarifications of the Initial OIG Safe Harbor Provisions and Establishment of Additional Safe Harbor

Provisions Under the Anti-Kickback Statueâ, 64 Federal Register 63526, (11/19/99).

8âHealthcare Valuation: The Financial Appraisal of Enterprises, Assets, and Servicesâ By Robert James Cimasi, Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.,

2014, p. 938.

9âFair Market Value: Analysis and Tools to Comply With Stark and Anti-kickback Rules,â By: Robert A. Wade, Esq. and Marcie Rose Levine, Esq Audio Conference,

HCPro, Inc., (March 19, 2008), p.49.

10âThe Health Care M&A Report: First Quarter 2014â By Irving Levin Associates, Inc., Norwalk, CT, 2014, p. 7, 13.

11âHealthcare Valuation: The Financial Appraisal of Enterprises, Assets, and Servicesâ By Robert James Cimasi, Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.,

2013, p. 930.

12âDeal Volume by Healthcare Sectorâ in âThe Health Care M&A Report: First Quarter 2014â By Irving Levin Associates, Inc., Norwalk, CT, 2014, p. 8.

13âHealthcare Valuation: The Financial Appraisal of Enterprises, Assets, and Servicesâ By Robert James Cimasi, MHA, ASA, FRICS, MCBA, AVA, CM&AA, Hoboken,

NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2013, p. 930.

14âMedicare and Medicaid Programs: Physiciansâ Referrals to Health Care Entities with which They Have Financial Relationshipsâ, 63 Fed. Reg. 1700 (1/9/98).

15âMedicare Program: Physiciansâ Referrals to Healthcare Entities with which They Have Financial Relationships (Phase II)â, 69 Fed. Reg. 16093 (3/26/04).

16“Reasonable Compensationâ By Jean Wright and Jay H. Rotz, Exempt Organizations Continuing Professional Education (1993), p. 3, http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-tege/eotopici93.pdf (Accessed 9/4/2012).

17“Publication 535 – Business Expenses”, Internal Revenue Service, 3/4/13, p. 6, http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p535.pdf (Accessed 4/1/13).

18“Excess Benefit Transaction”, 26 CFR Sections 53.4958-4(ii) (2012).

19“Subpart C: Permissive Exclusions – Exceptions”, 42 CFR Section 1001.952 (2012).

20âHealthcare Valuation: The Financial Appraisal of Enterprises, Assets, and Servicesâ By Robert James Cimasi, Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.,

2014, p. 939.

21âMedicare and Medicaid Programs: Physiciansâ Referrals to Health Care Entities With Which They Have Financial Relationshipsâ 66 Fed. Reg. 944 (Jan. 4, 2001).

22âMedicare and Medicaid Programs: Physiciansâ Referrals to Health Care Entities with which They Have Financial Relationshipsâ, 63 Fed. Reg. 1700, (1/9/98).

23âLimitation on Certain Physician Referralsâ, 42 USC 1395nn, (1/3/12).

24âOIG Advisory Opinion Number 03-8â, Office of Inspector General, (4/3/03).

25âPublication of the OIG Special Advisory Bulletin on Gainsharing Arrangements and CMPs for Hospital Payments to Physicians to Reduce or Limit Services to

Beneficiariesâ, 64 Federal Register 37985 (7/14/99).

26âHealthcare Valuation: The Financial Appraisal of Enterprises, Assets, and Servicesâ By Robert James Cimasi, Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.,

2014, p. 941.

27âMedicare and State Health Care Programs: Fraud and Abuse: Clarification of the Initial OIG Safe Harbor Provisions and Establishment of Additional Safe Harbor

Provisions under the Anti-Kickback Statuteâ, 64 Federal Register 63525, (11/19/99).

28âMedicare and State Health Care Programs: Fraud and Abuse: Clarification of the Initial OIG Safe Harbor Provisions and Establishment of Additional Safe Harbor

Provisions Under the Anti-Kickback Statuteâ, 64 Federal Register 63525Â (11/19/99).

29âUnrelated Business Activityâ, 26 USC Section 513(c) (1/3/12).

30âHealthcare Valuation: The Financial Appraisal of Enterprises, Assets, and Servicesâ By Robert James Cimasi, Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.,

2014, p. 944-945.

31âHealthcare Valuation: The Financial Appraisal of Enterprises, Assets, and Servicesâ By Robert James Cimasi, Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.,

2014, p. 946.

32âHealthcare Valuation: The Financial Appraisal of Enterprises, Assets, and Servicesâ By Robert James Cimasi, Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.,

2014, p. 946-947.

33âOIG Supplemental Compliance Program Guidance for Hospitalsâ, 70 Federal Register 4866 (1/31/05).

34âTrade or Business Expenses for Itemized Deductions for Individuals and Corporations for the Computation of Taxable Income for Normal Taxes and

Surtaxesâ, 26 USC Section 162(a) (1/3/12).

35âDeducting Business Expensesâ, Internal Revenue Service, 1/2/2013, http://www.irs.gov/Businesses/Small-Businesses-&-Self-Employed/Deducting-Business-Expenses (Accessed 2/26/13).

36âTrade or Business Expenses for Itemized Deductions for Individuals and Corporations for the Computation of Taxable Income for Normal Taxes and

Surtaxesâ, 26 USC Section 162(a) (1/3/12).

37âDeducting Business Expensesâ, Internal Revenue Service, 1/2/2013, http://www.irs.gov/Businesses/Small-Businesses-&-Self-Employed/Deducting-Business-Expenses (Accessed 2/26/13).

38âPublication 535 â Business Expensesâ, Internal Revenue Service, 2011, http://www.irs.gov/publications/p535/ch02.html (Accessed 2/25/13).

39âIRS Exempt Organizations Hospital Compliance Project: Final Reportâ, Internal Revenue Service, 11/7/08, p. 136.

40âPublication 535 â Business Expensesâ, Internal Revenue Service, 2011, http://www.irs.gov/publications/p535/ch02.html (Accessed 2/25/13).

41âPhysician Compensation Arrangements: Management and Legal Trendsâ, By Daniel Zismer, Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers, 1999, p. 204.

42âMedicare and State Health Care Programs: Fraud and Abuse: Clarification of the Initial OIG Safe Harbor Provisions and Establishment of Additional Safe Harbor

Provisions Under the Anti-Kickback Statuteâ, 64 Federal Register 63525Â (11/19/99).

43âTrade or Business Expenses for Itemized Deductions for Individuals and Corporations for the Computation of Taxable Income for Normal Taxes and

Surtaxesâ, 26 USC Section 162(a) (1/3/12).

44âUnrelated Trade or Businessâ in âTaxation of Business Income of Certain Exempt Organizationsâ, 26 USC Section 513(c) (1/3/12).

45âTrade or Business Expenses for Itemized Deductions for Individuals and Corporations for the Computation of Taxable Income for Normal Taxes and

Surtaxesâ, 26 USC Section(a) 162 (1/3/12).

46âIRS Revenue Ruling 69-383, 1969-2 CB 113â, Internal Revenue Service, 1969.

47âHealth Care Provider Reference Guideâ, By Janet Gitterman and Marvin Friedlander, Internal Revenue Service, 2004, p. 19.

48âMedicare and Medicaid Programs: Physiciansâ Referrals to Health Care Entities with Which They Have Financial Relationshipsâ, 63 Federal Register 1700

(1/9/98).

49âPublication 535 â Business Expensesâ, Internal Revenue Service, 2011, http://www.irs.gov/publications/p535/ch02.html

(Accessed 2/25/13).

50âPublication 535 â Business Expensesâ, Internal Revenue Service, 2011, http://www.irs.gov/publications/p535/ch02.html

(Accessed 2/25/13).

51âPublication 535 â Business Expensesâ, Internal Revenue Service, 2011, http://www.irs.gov/publications/p535/ch02.html

(Accessed 2/25/13).

52âPhysician Compensation Arrangements: Management and Legal Trendsâ, By Daniel Zismer, Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers, 1999, p. 204.

53âIRS Exempt Organizations: Hospital Compliance Project â Final Reportâ, Internal Revenue Service, 11/7/08, p. 136.

54âHealthcare Valuation: The Financial Appraisal of Enterprises, Assets, and Servicesâ By Robert James Cimasi, Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.,

2014, p. 955.

55âPublication 535 â Business Expensesâ, Internal Revenue Service, 2011, http://www.irs.gov/publications/p535/ch02.html (Accessed 2/25/13).

56âIRS Exempt Organizations Hospital Compliance Project: Final Reportâ, Internal Revenue Service, 11/7/08, p. 136.Â

57âPhysician Compensation Arrangements: Management and Legal Trendsâ, By Daniel Zismer, Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers, 1999, p. 204.

58âPublication 535 â Business Expensesâ, Internal Revenue Service, 2011, http://www.irs.gov/publications/p535/ch02.html (Accessed 2/25/13). Note that the commentary below offers justification for paying physicians at higher rates per unit of productivity than they historically earned in private practice.

59âFailure by Certain Charitable Organizations to Meet Certain Qualification Requirements: Taxes on Excess Benefitsâ, 63 Federal Register 41493 (8/4/1998).

60âOIG Supplemental Compliance Program Guidance for Hospitalsâ, 70 Federal Register 4867 (1/31/05).

61âOIG Supplemental Compliance Program Guidance for Hospitalsâ, 70 Federal Register 4867 (1/31/05).

62âPrinciples of Reasonable Cost Reimbursement; Payment for End-Stage Renal Disease Servicesâ Optional Prospectively Determined Payment Rates for Skilled

Nursing Facilitiesâ, 42 CFR 413.130(b)(2)(i) (10/1/12).

63âPrinciples of Reasonable Cost Reimbursement; Payment for End-Stage Renal Disease Servicesâ Optional Prospectively Determined Payment Rates for Skilled

Nursing Facilitiesâ, 42 CFR 413.130(b)(2)(i) (10/1/12).

64âFair Market Valuation of Medical Director of Program Director Servicesâ, By Kathy McNamara, Mayer Hoffman McCann PC, 7/12/05, in Plaintiff United Statesâ Designation of Expert Witness, âUnited States ex rel. Kaczmarczyk, et. al. v. SCCI Hospital Houston Central, et. alâ No. H-99-1031 (S.D.T.X. 2005).

65âFair Market Valuation of Medical Director of Program Director Servicesâ, By Kathy McNamara, Mayer Hoffman McCann PC, 7/12/05, in Plaintiff United Statesâ Designation of Expert Witness, âUnited States ex rel. Kaczmarczyk, et. al. v. SCCI Hospital Houston Central, et. alâ No. H-99-1031 (S.D.T.X. 2005).

66âU.S. ex rel. Ted Kosenske, MD, v Carlisle HMA, Inc., and Health Managements Associates, Inc,â 07-4616 US District Court 05-cv-02184, (1/21/09), p. 18.

67âOIG Advisory Opinion Number 12-09â, Office of Inspector General, 7/23/12, p. 6-7.

68âStatements of Antitrust Enforcement Policy in Health Careâ, US Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission, August 1996, p. 4.

69âStatements of Antitrust Enforcement Policy in Health Careâ, US Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission, August 1996, p. 13.

70âStatements of Antitrust Enforcement Policy in Health Careâ, US Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission, August 1996, p. 66.

71âNorman PHO Advisory Opinionâ, Federal Trade Commission, 2/13/13, p. 13, http://www.ftc.gov/os/2013/02/130213normanphoadvltr.pdf (Accessed 4/1/13).

72âNorman PHO Advisory Opinionâ, Federal Trade Commission, 2/13/13, p. 13, http://www.ftc.gov/os/2013/02/130213normanphoadvltr.pdf (Accessed 4/1/13).

73âStatements of Antitrust Enforcement Policy in Health Careâ, US Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission, August 1996, p. 11.

74âProhibition of Certain Referralsâ 42 U.S.C. Section 1395nn(a)(1)(A) (2010).

75âHealth Care Fraud and Abuse: Practical Perspectivesâ Edited by Linda A. Baumann, Washington, DC: American Bar Association, 2002, p. 106.; âExceptions to the Referral Prohibition Related to Compensation Arrangementsâ 42 C.F.R. Section 411.357 (10/3/08); âLimitations on certain physician referrals,â âLimitation on Certain Physician Referralsâ 42 U.S.C. Sections 1395nn(a)-(e), (2012).

76âIllegal Remunerationsâ 42 U.S.C. Section 1320a-7b(b) (2012).

77âHealthcare Valuation: The Four Pillars of Healthcare Valueâ By Robert James Cimasi, Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2014, p. 305.

78âIllegal Remunerationsâ 42 U.S.C. 1320a-7b(b)(3)(B) (2012); âLimitations on Certain Physician Referralsâ 42 U.S.C. Section 1395nn(a)(1) (2012); âPersonal Services and Management Contractsâ 42 CFR Section 1001.952(d) (2007); âBona Fide Employment Relationshipsâ 42 USC Section 1395nn(e)(2) (2010); âAcademic Medical Centersâ 42 CFR Section 411.355(e)(ii)(B) (2010); âExceptions to the Referral Prohibition Related to Compensation Arrangementsâ 42 CFR Section 411.357 (2010).

79âDefinition of Excess Benefit Transactionâ 26 CFR Section 53.4958-4(a)(1)Â (2002).

80âRebuttable Presumption that a Transaction is not an Excess Benefit Transactionâ 26 CFR Section 53.4958-6 (2002).

81âHealthcare Valuation: The Financial Appraisal of Enterprises, Assets, and Servicesâ By Robert James Cimasi, Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2014, p. 965.

82âHealthcare Valuation: The Financial Appraisal of Enterprises, Assets, and Servicesâ By Robert James Cimasi, Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2014, p. 964-968.