Is Solvency in the Eye of the Beholder?

Recognizing Hindsight and Projection Bias

How can one expert opine that the company is insolvent and another expert—viewing the same financial statement—opine that the company is solvent? In this article, Michael Vitti answers this question and provides an overview of what is considered a preference and a fraudulent transfer.

Valuation professionals often arrive at starkly different conclusions when assessing a debtor’s solvency in a litigation context. Solvency analyses typically consist of two key binary (pass/fail) tests: (1) balance sheet and (2) adequate capital. The plaintiff’s expert will often opine that the debtor failed both of these tests by a significant margin. Conversely, the defendant’s expert will usually opine that the debtor passed both of these tests by a significant margin. A neutral observer might think that these experts are assessing the financial condition of different companies.

Valuation professionals often arrive at starkly different conclusions when assessing a debtor’s solvency in a litigation context. Solvency analyses typically consist of two key binary (pass/fail) tests: (1) balance sheet and (2) adequate capital. The plaintiff’s expert will often opine that the debtor failed both of these tests by a significant margin. Conversely, the defendant’s expert will usually opine that the debtor passed both of these tests by a significant margin. A neutral observer might think that these experts are assessing the financial condition of different companies.

The disparate conclusions can be driven by differences in opinions across many topics. This article summarizes some of these debates, which will be addressed in greater number and more detail during the upcoming Advanced Business Valuation Symposium on December 10, 20141. For further context, also see my three-part paper in Business Valuation Review2.

Brief Overview of Solvency-Related Law

There are two types of lawsuits that allow the trustee to claw back certain transfers that were made prior to the debtor’s bankruptcy filing. Both types of lawsuits require the trustee to prove that the debtor was insolvent when the transfer was made.

Preference lawsuits address the repayment of antecedent debt that occurred shortly before the debtor filed for bankruptcy. These lawsuits address instances where the debtor effectively robbed Peter to pay Paul, which results in preferential treatment for Paul.

Fraudulent transfer lawsuits address other transfers (e.g., dividends) that occurred over a longer period before the debtor filed for bankruptcy. These lawsuits address instances where the debtor gave up assets, or took on a liability, in exchange for consideration that was less than reasonably equivalent value.

Brief Overview of the Two Key Financial Tests of Solvency

The balance sheet test is easy to define. If assets are less than liabilities, the debtor fails this test. If assets are greater than liabilities, the debtor passes this test.

The execution of this test is more complicated. Assets must be valued at a fair valuation, which is an undefined term in the law. Opposing experts may quibble over the standard and premise of value to be used. Even if the experts agree on the appropriate standard and premise of value, one expert will arrive at relatively low values whereas the other expert will arrive at relatively high values.

The adequate capital test is difficult to define. A company that has unreasonably small assets (a.k.a., inadequate capital) fails this test. A company that has adequate capital passes this test. “Unreasonably small assets” and “adequate capital” are undefined terms in the law and have no meaning without context. It could be said that the definition for this test is similar to Justice Potter Stewart’s definition of pornography: “I know it when I see it.”

As a practical matter, this test consists of two components. First, analyses from the balance sheet test (e.g., projected income statements, balance sheets, and cash flow statements) carry over to this test. Second, reasonable benchmarks to assess the adequacy of capital must be set. Experts will typically disagree over both components.

Plan to Succeed vs. Hindsight Bias

The fact pattern in these disputes is often the same. The contemporaneous projections depict a debtor with a positive outlook. Investors often demonstrate their faith in these projections by putting substantial capital at risk. Unfortunately for the debtor and these investors, the debtor subsequently performed worse than projected, which ultimately resulted in its bankruptcy filing.

The plaintiff’s expert will argue that the contemporaneous projections were not reliable. This expert may argue that the contemporaneous projections were prepared by management with a “can do” attitude. Thus, the projections reflect a hopeful plan to succeed, not a more realistic depiction of a company doomed to fail. The plaintiff’s expert will then reduce the contemporaneous projections to reflect his view of what was realistic at the time.

The defendant’s expert will often counter that the contemporaneous projections were realistic and that the plaintiff’s expert’s opinions are influenced by hindsight bias. There are two types of hindsight bias. Explicit hindsight uses events that occurred after-the-fact to directly influence assessments as of the earlier transfer date. Implicit hindsight is more subtle as the plaintiff’s expert can still appear, at least superficially, to be performing a forward-looking analysis as of the transfer date. An expert who uses implicit hindsight diligently searches for negative facts and/or de-emphasizes positive facts in the contemporaneous record. This expert supports this approach, at least in part, based on what actually happened.

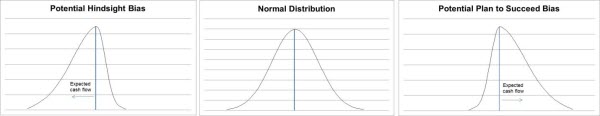

See Figure 1 for a graphical illustration of de-emphasizing certain information.3

Figure 1

Discount Rates

Not surprisingly, the plaintiff’s expert will often use relatively high discount rates whereas the defendant’s expert will often use relatively low discount rates. This outcome is interesting given the allegations of hindsight and plan to succeed bias.

A market-based discount rate must be applied to expected cash flows (e.g., the mid-point in the normal distribution from Figure 1). Both experts will claim to use a market-based discount rate and expected cash flows. However, the plaintiff’s expert is overstating risk if he applies a market-based discount rate to biased low cash flows. Similarly, the defendant’s expert is understating risk if he applies a market-based discount rate to biased high cash flows.

Instead of reducing the difference between the two valuations, the discount rate often widens the difference. The experts often won’t even agree to use the same assumptions for all of the factors that are unrelated to the debtor (e.g., the equity risk premium for the overall market). Not surprisingly, the plaintiff’s expert’s assumptions typically result in higher discount rates whereas the defendant’s expert’s assumptions typically result in lower discount rates.

Comparability of Guideline Companies

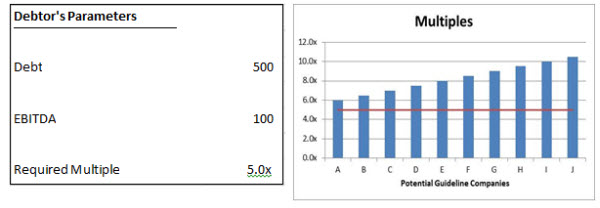

It is common for one expert to opine that the guideline companies were reasonably comparable whereas the other expert opines that they were not. This typically occurs when the multiple for any of the guideline companies results in the debtor passing, or failing, the balance sheet test. See Figure 2 for an example where the multiple of any company results in the passing of the balance sheet test.

It is also common for one expert to choose companies with relatively high multiples whereas the other expert chooses companies with relatively low multiples. For example, if the required multiple to pass the test in the figure above was 7.0 times instead of 5.0 times, the plaintiff’s expert would likely focus on companies A and B (multiples of 6.0 and 6.5 times, respectively) whereas the defendant’s expert would likely focus on companies D thru J (multiples ranging from 7.5 to 10.5 times). Each expert, in this instance, will accuse the other expert of using selection bias.

Demonstrated Ability to Survive Subsequent (Financial) Storms

A debtor needs adequate capital in order to survive reasonable (financial) storms that may afflict it. The Great Recession unleashed the proverbial “category 5 hurricane” on the financial markets. Some debtors that are the subject of fraudulent conveyance lawsuits were able to delay their bankruptcy filing for a period after this storm was unleashed.

The defendant’s expert may argue that the debtor’s subsequent ability to survive this hurricane for a sustained period is evidence that the debtor was adequately capitalized. After all, what better test of adequate capital is there than the ability to survive (for a period) such a storm?

The plaintiff’s expert may counter that, paradoxically, a super storm is beneficial to debtors. This is based on the observation that some creditors, out of their own self-interest, chose to be forbearing when a “perfect storm” hits. This activity is colloquially referred to as “extend and pretend” or “delay and pray.”

The Decider: Contemporaneous Market Data

The parties generally treat contemporaneous market data differently. One party typically places a lot of emphasis on this information (when it consistent with their position) while the other party tries to discredit it (when it is inconsistent with their position).

Nevertheless, courts often focus on what contemporaneous market participants believed at the time. These market participants made their decisions in real time (thus they are not influenced by hindsight) and outside the context of litigation.

Some may argue that contemporaneous market participants are biased or that markets are inefficient. Others may argue that the price of a security is not the same as the value of a security.

As a practical matter, deferring to contemporaneous market data is often the most parsimonious choice. It is logical for finders of fact to ground their decisions in this information, especially in light of the chasm in proffered assessments by the dueling experts. Contemporaneous market data may not be perfect, but as Voltaire famously stated, “perfect is the enemy of good.” Decisions made by contemporaneous market participants are often deemed to be good enough in the context of retrospective solvency assessments.

Thus, contemporaneous market data is the anchor that differentiates the definition of solvency from the definition of beauty.

Michael Vitti, CFA, joined Duff & Phelps in 2005. He is a managing director in the Morristown office and part of the firm’s Dispute and Legal Management Consulting practice. He is also a member of the firm’s Complex Valuation and Bankruptcy Litigation group, focusing on issues related to valuation and solvency. Michael has more than 17 years of valuation experience. Mr. Vitti can be reached at Michael.Viti@duffandphelps.com or at (973) 775-8300.

1 http://www.nacva.com/CTI/CTIAdvancedBVSymposium.asp

2 Michael Vitti (2013). “Grounding Retrospective Solvency Analyses in Contemporaneous Information: Part I.” Business Valuation Review: Winter 2013, Vol. 32, No. 4, pp. 186-211; Michael Vitti (2014). “Grounding Retrospective Solvency Analyses in Contemporaneous Information (2 of 3). Business Valuation Review: Summer 2014, Vol. 33, No. 1-2, pp. 3-20; Michael Vitti (2014). “Grounding Retrospective Solvency Analyses in Contemporaneous Information (3 of 3).” Business Valuation Review: Fall 2014, Vol. 33, No. 3, pp. 50-80.

3 An increased emphasis on negative or positive events would result in fatter tails in that direction (i.e., a fatter left tail in the left chart and a fatter right tail in the right chart).