Difficulty with Applying the Contract Rate Approach to Chapter 11 Bankruptcy

A Case Study, Part 2 of 2

In this second part of the article, Dr. Allyn Needham examines post-Till cases from the northern and western districts of Texas, highlights the problems encountered using the Formula Approach, and tests whether the Contract Approach may have provided a better approach and reduced the incidence of litigation where a cramdown is proposed. Ultimately, Dr. Needham proposes that despite the problems presented by the Formula Approach, the Contract Approach is not a panacea for Chapter 11 bankruptcy matters. Business valuators practicing in this area must understand case precedent and recognize the limits of the proposed approaches.

In this second part of the article, Dr. Needham examines six post-Till cases where the Formula Approach was followed and examines whether the Contract Approach may have reduced the incidence of litigation and been fairer to debtors and creditors. To read Part 1, click here.

Case Study and Analysis

It is not unusual for something to be sound theoretically, but not workable practically. An examination of six Chapter 11 bankruptcy cases in the northern and western districts of Texas shows this to be true with the application of the Contract Approach.

All of these cases were filed post-Till. They were taken from the files of Shipp, Needham & Durham, LLC.[22]Â Each case required a cramdown analysis to determine the interest rate for a secured claim in a court that had found Till instructive and directive.[23]

- Dallas Apartment Complex: A 237-unit apartment complex in Dallas, Texas. It was an existing complex in full operation.[24]

- Austin Condominiums: A new development in Austin, Texas. The site contained a structure which had to be razed prior to the construction of the condominiums.[25]

- Oklahoma Shopping Center: A shopping center in Moore, Oklahoma comprised of approximately 260,000 square feet of retail space. Major retail tenants already occupied completed space. 17,925 square feet remained under construction.[26]

- Johnson County Motel: A 79-unit motel located in Cleburne, Texas. It was an existing complex in full operation.[27]

- Denver Market Center: A wholesale market center used for trade shows and special events in Denver, Colorado. It consists of four adjoining buildings that totaled approximately 810,000 square feet in size. It was an existing complex in full operation.[28]

- Dallas Logistics Center: A master plan development of approximately 5,500 acres in Dallas, Texas. There had been limited development with the majority of the acreage remaining vacant undeveloped land.[29]Â

Contract Rates and Risk Premia

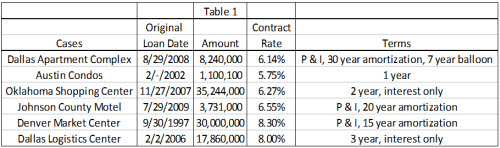

The initial review included determining the date of the original loan, the amount borrowed, the contract rate, and terms of repayment. Table 1 shows the results.

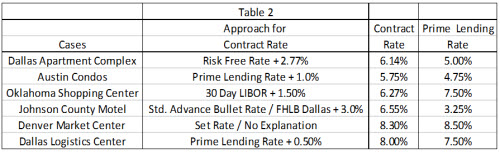

As the second part of this review, the approach used to arrive at the contract rate and the prime lending rate at the time the loan originated were determined.[30] Table 2 shows the results from that search.

Table 1 shows that these secured loans had varying durations. Some were permanent financing. While others were interim loans for construction and/or completion of real estate ventures.

Table 2 shows the ways lenders approached determining the contract rate. According to the loan documents, these lending institutions (with the exception of the Denver Marker Center) used a Formula Approach for determining the contract rate for these loans.

More specifically, the lenders used a Build-Up Method for constructing the contract rate. This means risk premia were added to a base rate. In general, the risk premia were based on the creditworthiness of the borrower, the quality of the collateral and the duration of the loan. Not only did the risk premia vary from borrower to borrower, but the base rate used for the calculation. Of the five loans reporting using the Build-Up Method, four different base rates were used.

These varying bases are defined as follows:

- Risk free rate: Theoretically, the rate of return when the lender has zero risk. This does not exist. Therefore, U.S. Treasury Securities are used. In most real estate build-up formulas, the yield on U.S. Treasury bonds maturing ten years in the future is used.[31]

- Prime lending rate: The rate banks offer their most creditworthy customers for commercial loans. The prime lending rate reported in the Wall Street Journal and most news sources is the rate reported by the largest 30 banks in the U.S.[32]

- LIBOR: The London InterBank Offered Rate is the average interest rate at which a select group of large, reputable banks that participate in the London interbank money market can borrow unsecured funds from other banks. The rate is fixed on every business day in the United Kingdom.[33]

- Standard Advanced Bullet Rate of the Federal Home Loan Bank of Dallas: This rate is reported by the Dallas Federal Home Loan Bank. It reports the rate charged on fixed rate/fixed term loans maturing from one year to 20 years, interest only with principal to be paid at maturity.[34]

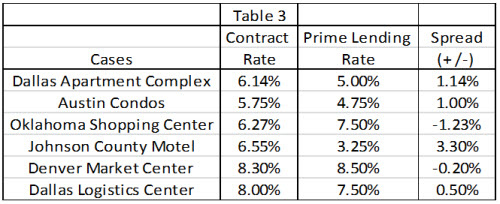

Justice Scalia noted the contract rate is “a good indicator of the actual risk.”[35] This analysis has estimated the risk associated with each loan by subtracting the prime lending rate at the date of the original loan from the contract rate. This provides a commonly known and accepted bases rate from examining the risk assumed by the lender when making the original loan. It also provides for comparison of the impact of market movement when the risk factors are applied to the current prime lending rate.

Table 3 shows the spread between the contract rate and the prime lending rate. Two of the cases (Oklahoma Shopping Center, Denver Market Center) reported contract rates less than the prime lending rate at the time the loan originated. In comparison to the Till formula range (prime lending rate plus one percent to three percent), the Dallas Logistics Center rate was less than the range minimum risk factor (1.0 percent) and the Johnson County Motel was greater than the maximum risk factor (3.0 percent). The remaining two loans were within the Till range.

Market Interest Rate Movement

Justice Scalia also noted that interest rates may increase or decrease in the interim between the loan being made and the effective date of the proposed reorganization. “[I]f market interest rates generally have risen or fallen since the contract was executed, the contract rate could be adjusted by the same amount cases where the difference was substantial enough that a party chose to make an issue of it.”[36]

Table 4 shows the highest and lowest prime lending rate for each year from 2004 through 2014.[37] A review of the movement in the prime lending rate over this period reveals a 500 basis point drop from 2007 through 2008. [38] Â It appears this would be the type of market interest rate movement anticipated by Justice Scalia.

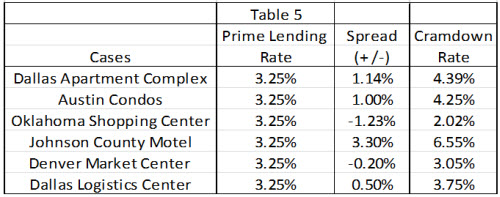

Assuming that the contract rate reflects the risk accepted by the lender at the time the original loan was made, the spread between the contract rate and the current prime lending rate would maintain—in theory—the same level of risk, relative to current market rates.

Table 5 shows the anticipated cramdown interest rates when the risk premia are applied to the current prime lending rate as of 2014. These new rates reflect the spreads between the prime lending rate at the time of the original loan and the original contract rate added to the current prime lending rate.

When adjusted for the current prime lending rate, the Oklahoma Shopping Center rate falls from 6.27 percent to 2.02 percent. The Denver Market Center rate falls from 8.30 Â percent to 3.05 percent. Only the Johnson County Motel rate remains the same having been made when the prime lending rate was 3.25 percent, the same as the current prime lending rate.

The Denver Market Center provides a perfect example of the problems with applying the contract rate. If the original contract rate (8.30 percent) was retained, the creditor would (ostensibly) be satisfied and the debtor objecting. If the rate was adjusted for the movement in interest rates, the debtor would be satisfied with the new rate (3.05 percent) and the creditor would be objecting.

The difficulties with applying the contract rate are not just limited to the rate itself. There are other issues which impact the assessment. As an example, both the Oklahoma Shopping Center and the Dallas Logistics Center had modifications to their loans that demonstrated the increasing risk exposure to the lender. The Oklahoma Shopping Center was modified eight times with the formula used in determining the contract rate increasing from the 30 day LIBOR plus 1.50 percent to the 30 LIBOR plus 6.0 percent. The Dallas Logistics Center rate increased from the prime lending rate plus 0.50 percent to the prime lending rate plus 3.0 percent. The choice of which contract rate to apply would have significant impact on the reorganization and repayment plans.

Perhaps more importantly, the contract rate, whether the original rate or one of the modifications, represents the condition of the debtor and the lending environment at the time the loan was originated, renewed or modified. The proposed repayment plan is addressing the condition of the debtor and the lending environment at the time of confirmation.

Other Factors Impacting Rates/Terms for the Repayment

Other factors impact the rates and terms of repayment. This may be seen in a number of differences between the proposed repayment plan and the original loan. As an example, the terms of the repayment plan may not be the same as the original terms of the loan. Table 1 shows that three of the loans had been amortized over a period of years. The other three loans were short term, three years or less. Most repayment plans propose amortized notes with possible balloon payments after a number of years.

Generally, interest rates will vary depending on the length of the repayment period, the longer the payout period, the greater the interest rate. Therefore, the contract rate on a short term loan may not be sufficient to cover the risk over a longer pay out period.Â

Other Factors Impacting Rates/Loan to Value Ratio

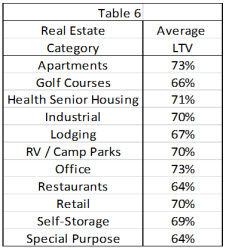

While the terms for the repayment may be different between the original loan and the proposed repayment plan, it is also likely that the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio will be as well. A review of the Fourth Quarter 2014 Investor Survey by RealtyRates.com, shows average commercial real estate LTV ratios ranging from 64 to 73 percent.[39] This survey pools 312 appraisal and brokerage firms, developers, investors, and lenders nationwide. Table 6 shows the average LTV ratios for the various real estate categories.

These figures reflect the collateral cushion lenders, on average, want when making loans for these types of commercial projects. The lender will incorporate this collateral cushion into its calculation of the contract rate. Generally, when assessing the LTV ratio, the greater the LTV ratio, the greater the risk to the lender and the greater the interest rate.

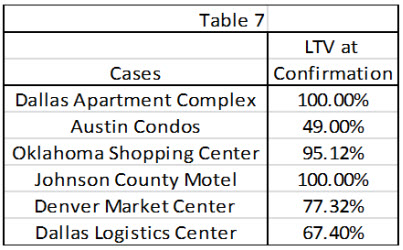

Table 7 shows the LTV ratios at the time of confirmation for the six cases in this study. These figures reflect the LTV ratios generated by the collateral values and allowed secured claim amounts set by the courts for their contested hearings.

Only two of the cases had LTV ratios that were similar to or below the average LTV ratios sought by lenders. This too questions the applicability of using the contract rate, because the level of security on which the contract rate was determined no longer exists.

Other Factors Impacting Rates

There are other factors that may impact the consideration of the cramdown rate that was not anticipated when the contract rate was determined. Here are some common examples:

- The debtor/collateral may not be producing cash flow. Some of the elements influencing this factor may include the original loan’s anticipated completion of a construction project, the rental of that property or occupancy by the debtor, cash flow being generated by lease payments, or revenue generated by the debtor’s business. If a project is not completed or only partially leased or the debtor’s business not grown as expected, the cash flow will not be as projected. Therefore, the risk factor relating to the cash flow projections may be incorrect.

- The original loan may be supported by personal guarantees from individuals related to the debtor (owner, shareholders, investors). They may also have sought bankruptcy protection and are no longer able to provide personal guarantees for the new note. Therefore, any risk reduction considered with the original loan is no longer applicable.

- The original loan may have been sold to another lender or investor group. The new note holder did not participate in the risk assessment prior to the original loan. This new owner brings a different thought process in evaluating risk and expected returns.

Conclusion

In his Till dissent, Justice Scalia argued for the use of the contract rate as the presumptive rate for a cramdown rate on a secured claim. But his opinion allowed debtors or creditors to argue that the movement in market interest rates between the origination of the loan and the confirmation hearing should require an adjustment to the interest rate.

Recent history shows the potential problem with the Contract Rate Approach and market interest rate movement. The prime lending rate fell from 8.25 percent in 2007 to 3.25 percent in 2008 and has remained at that low level through 2014 due to the Federal Reserve’s intervention in the markets between 2008 and late 2014; QE 3 ended in October 2014.  Under the Contract Approach, debtors would seek lower interest rates by asking bankruptcy courts to consider hearing arguments about the movement in market interest rates since the origination of a loan and how this movement should affect the interest rate to be applied to its repayment plan.

Conversely, it is anticipated that interest rates (the prime lending rate included) will begin to climb in 2015 with the end of quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve Bank.[40] As interest rates move higher, creditors will begin seeking higher interest rates by asking bankruptcy courts to consider hearing arguments about the movement in market interest rates since the origination of a loan and how this movement should affect the interest rate to be applied to the repayment plan.

Therefore, during periods of interest rate movements, cramdown hearings should be expected regardless the interest rate approach, Formula or Contract Rate, for assessing the cramdown rate. Should the contract rate be used, it may over-reward the creditor relative to the current lending environment as exemplified by the Denver Market Center contract rate of 8.30 percent. Should the rate be adjusted to reflect the change in the market interest rates, it could over reward the debtor relative to the current lending environment as exemplified by the Oklahoma Center Shopping Center whose contract rate was 1.23 percent below the prime lending rate. This would provide a cramdown rate of 2.02 percent based on a 3.25 percent prime lending rate.

But even during periods of relatively constant interest rates, the use of the Contract Approach has its limitations. Some of these are the loss of the collateral cushion and the increase in the LTV ratio, the unanticipated impairment of the debtor’s cash flow, the loss of personal guarantees, and/or the sale of the note to a new lender or investor group.

These show that the Contract Rate Approach is not a panacea for determining the cramdown rate in Chapter 11 matters. The complexity of Chapter 11 matters, relative to Chapter 13 personal bankruptcies, makes it almost certain that no approach will satisfy debtors and creditors and provide for non-contested proceedings.

A review of the debtor’s loan history may provide important information about the risk factors considered by the lender as the debtor moved toward bankruptcy. The contract rate of the original loan and the contract rate as adjusted by subsequent modifications would be part of that assessment.

But it appears the bankruptcy court will be more concerned with the current condition of the debtor and the lending market, not the past:

[C]ourts typically select a [cramdown] rate on the basis of holistic assessment of risk of the debtor’s default on its restructured obligations, evaluating factors including quality of the debtor’s management, the commitment of the debtor’s owners, the health and future prospects of the debtor’s business, the quality of the lender’s collateral and the feasibility and duration of the plan.[41]

In this opinion, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals expands the Till factors. The discussed risk factors relate to the current condition of the debtor and the commitment by its management and owners for the debtor’s long term survival. These risks are relating to matters that are current or moving forward, not the circumstances relating to the original loan.  Because of this, the Contract Rate Approach cannot be the final word in determining the cramdown interest rate to be applied to a Chapter 11 repayment plan.

Â

Allyn Needham, PhD, CEA, is a principal at Shipp, Needham & Durham, LLC (Fort Worth, Texas). For the past 17 years, he has worked in the area of litigation support. Prior to that, Dr. Needham worked more than 20 years in the area of banking and risk management. Dr. Needham has also been an adjunct professor of economics at Texas Christian University and Weatherford College. As an expert, he has testified on various matters in state and federal courts relating to commercial damages, personal damages, business bankruptcy and business valuation. Dr. Needham can be reached at aneedham@shippneedham.com and (817) 348-021

Â

References

“Bank Prime Lending Rate Changes, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis,” http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/data/PRIME.txt

Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act (2005).

“Basis Points,” Investopedia, http://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/basispoint.asp.

“Interest Rates, Rates Overview,” Federal Home Loan Bank Dallas, www.fhlb.com/rates/rates_overview.html

“Investor Survey 4th Quarter 2014,” RealtyRates.com, www.realtyrates.com

“London InterBank Offered Rate,” FedPrimeRate, http://fedprimerate.com/libor/index.html

Needham, Allyn, and Schroeder, Kristin, “Cram Down Interest Rate Analysis in Chapter 11 Bankruptcy Matters: An Overview,” The Earnings Analyst, Vol. 12, 2012, 23.

“Prime Interest Rate,” FedPrimeRate.com, http://fedprimerate.com

“Quantitative Easing,” Investopedia, http://www.investopedia.com/terms/q/quantitative-easing.asp

Risk Free Rate of Return, Investopedia, http://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/risk-freerate.asp

“Risk Premium,” Investopedia, http://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/riskpremium.asp

Marotta, David John. “What Exactly Is Quantitative Easing?” Forbes, May 5, 2014.

“When Will Quantitative Easing End?,” www.abcnews.go.com.

Wong, Daniel, “Chapter 11 Bankruptcy and Cramdowns: Adopting a Contract Rate Approach,” Northwestern Law Review, Vol. 106, No. 4, 2012, 1927‒58.

Cases

Till v. SCS Credit Corp., 541 US 465 (2004)

In re: Mirant Corp., 334 B.R. 800 (Bankr. N.D. Tex. 2005)

In re: Northwest Timberline Enterprises, Inc., 348 B.R. 412 (Bankr. N.D. Tex. 2006)

In re: Texas Grand Prairie Hotel Realty, LLC, 710 F.3d 324; 2013 U.S. App. LEXIS 4514; 57 Bankr. CT. Dec. 177)

In Re: American Home Patient, Inc., 450 F.3d 559, 565-566, (6th Cir. 2005)

In Re: Kidd, 315 F.3d 671, (6th Cir. 2003)

GMAC v. Valenti (In Re: Valenti), 105 F.3d 55, (2nd Cir. 1997)

[22] Shipp, Needham & Durham, LLC, www.shippneedham.com, is an economic consulting firm located in Fort Worth, Texas specializing in litigation support. The firm’s experts work in the areas of personal damages, commercial damages, and business bankruptcy.

[23]Allyn Needham, the author of this article, acted as an interest rate expert in each of these cases. In some of these cases, he worked for counsel representing the debtor(s). In other cases, Dr. Needham worked for counsel representing the creditor(s). The data discussed in this report come from reorganization plans, disclosure statements and attached exhibits. These documents are public record and are available through PACER. None of the disclosed data are from confidential records.

[24] In Re: Santa Fe Apartments, LP f/k/a Copper Canyon Village, JV, 11-31148-HDH-11, N.D. Tex.

[25]In Re: PPT Development, LP, 10-11497-HCM-11, W.D. Tex.

[26] In Re: Moore Sorrento, LLC, 11-44651-RFN-11, N.D. Tex.

[27] In Re: Shree-Hari Inc. d/b/a/ Motel 6, 12-30847-SCJ-11, N.D. Tex

[28] In Re: Denver Merchandise Mart, et. al., 11-3615-BJH-11, N.D. Tex

[29] In Re: DLH Master Land Holdings, LLC, Allen Capital Partners, LLC, et. al, 10-30561-HDH-11, N.D. Tex

[30] “Bank Prime Lending Rate Changes, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis,” http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/data/PRIME.txt

[31]“Risk Free Rate,” Investopedia, www.investopedia.com/terms/r/risk-freerate.asp

[32] “Prime Interest Rate,” http://fedprimerate.com

[33] “The London Interbank Offerred Rate,” http://fedprimerate.com/libor/index.html

[34] “Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) Dallas,” www.fhlb.com/rates/rates_overview.html

[35] Till, 492

[36] Till, 494 footnote 2.

[37] “Prime Loan Rate Changes, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis,” http://stlouisfed.org/fred2/data/PRIME.txt

[38] Basis point is defined as a unit equal to 1/100th of one percent. It is used to denote changes in a financial instrument. If an interest rate moves from 3.25 to 3.50 percent, the movement is 25 basis points.

[39] “Investor Survey 4th Quarter 2014,” RealtyRates.com, www.realtyrates.com.

[40] Quantitative easing is a program through which the central bank of a country purchases government securities or other securities from the market in order to lower interest rates and increase the money supply. It increases the money supply by increasing the capital in that country’s financial institutions to promote increased lending and liquidity. The Federal Reserve Bank has stated that the U.S. quantitative easing program will be reduced and that it should end in 2015 providing the domestic economy continues to expand. “Quantitative Easing,” Investopedia, www.investopedia.com; “What Is Quantitative Easing?,” 5/5/2014, Forbes Magazine, www.forbes.com; “When Will Quantitative Easing End?,” www.abcnews.go.com.

[41] In Re: Texas Grand Prairie Hotel Realty, LLC, 20

Image courtesy of anankkml/FreeDigitalPhotos.net