Using ESOPS in Succession Planning

A Case Study

An ESOP is one of many options available to business owners considering succession-planning options. There are substantial advantages, but there are also regulatory and cost considerations. A feasibility study may suggest whether the ESOP is an appropriate option. In this article, authors Kelly Finnell and Andrew Holmes share their views on when an ESOP is feasible using a case study.

Like people, businesses have life cycles. The final cycle in the life of a business is ownership succession planning, and it is during this cycle that a business owner hopes to realize his or her biggest payday and define and perpetuate his or her legacy. Possible ownership succession planning strategies include a sale to a third party, a sale to insiders, a transfer to family members, and a sale to an employee stock ownership Plan (ESOP). There is no “one-size-fits-all” solution in ownership succession planning; the best solution depends on the specific circumstances facing the business owner and the ownership succession planning goals he or she hopes to achieve. This article discusses ESOPs as an ownership succession planning strategy and illustrates the features and benefits that an ESOP provides through a case study involving a service company.

Like people, businesses have life cycles. The final cycle in the life of a business is ownership succession planning, and it is during this cycle that a business owner hopes to realize his or her biggest payday and define and perpetuate his or her legacy. Possible ownership succession planning strategies include a sale to a third party, a sale to insiders, a transfer to family members, and a sale to an employee stock ownership Plan (ESOP). There is no “one-size-fits-all” solution in ownership succession planning; the best solution depends on the specific circumstances facing the business owner and the ownership succession planning goals he or she hopes to achieve. This article discusses ESOPs as an ownership succession planning strategy and illustrates the features and benefits that an ESOP provides through a case study involving a service company.

Owners of successful, mature, private companies often have the opportunity to sell to “outsiders,”

including competitors and private-equity groups. While this option may have its advantages, it is not the best option in every situation. Disadvantages of selling to outsiders include the following:

Control: Many business owners want to be able to influence the direction of their company even after they have cashed out. Protecting and rewarding the key employees and family members who have helped build a successful enterprise are often part of a business owner’s succession planning goals. Often, a business owner wants to ensure that clients will have continuity in their relationships with the company and continue to receive the same high-quality service that has made them loyal clients. If business owners sell to a third party, they will likely lose control of the company and will not be able to influence its direction following the transaction.

Independence:Â One of the most common characteristics of successful entrepreneurs is that they are fiercely independent. The same personality traits that make them great entrepreneurs could result in them being miserable if they had to work for someone else. However, if an owner wants to sell, he or she often will have enter into an employment and non-compete contract for a two- to three-year period to ensure a successful transition of the business. The larger and more bureaucratic the purchaser, the bigger the challenge this employee transition period presents.

The Day After: After an owner sells and suffers through the post-transaction employee transition period, what’s next? For many hard-driving entrepreneurs, playing golf and doing charitable work simply does not provide the same level of fulfillment as building and operating a successful business. Often, they want to “have it all” by realizing the full value of the business and staying involved in their company in a strategic role, rather than being obligated to serve in an operating capacity. A sale to a third party almost never provides this opportunity.

Partial Sale:Â Some owners would like to realize liquidity from their business without selling all of the company. It can be challenging to find purchasers who are interested in acquiring less than 100 percent of a company, and it is virtually impossible to find purchasers who are willing to acquire less than 51 percent.

For owners who have these concerns, an ESOP is an attractive alternative. An ESOP allows business owners to sell all or a portion of their business, continue to control the company after the sale, and reward and retain their current employees. Further, an ESOP sale gives them as much freedom as they desire to begin their transition out of the company or stay involved in the business on a daily basis.

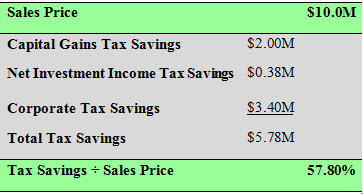

ESOPs also offer very attractive tax benefits for a selling business owner and his or her company. A sale to an ESOP can be structured so that the owner’s sales proceeds are taxed at long-term capital gains tax rates using the installment method, or so that the owner permanently defers paying tax on his or her sales proceeds. ESOPs also offer a way for a company to perform a leveraged buyout on a fully tax-deductible basis. In a traditional leveraged buyout, a company tax deducts interest payments on the transaction financing; however, in an ESOP transaction, a company may deduct interest and principal on the ESOP financing. On a combined basis, these tax benefits can provide a tax subsidy equal to more than 50 percent of the transaction price, as illustrated below:

Please note that the tax savings illustrated above only consider 2015 federal corporate and long-term capital gains tax rates. The impact of state taxes could make the tax savings of an ESOP even higher.

To help explain an ESOP’s mechanics and the many benefits it provides, this article presents a case study of a service company operating as a Subchapter S Corporation and whose founder owns 100 percent of its stock. The company has revenue in the amount of $15 million and annual free cash flow in the amount of $5 million, which includes an add-back for “excess” owner compensation, or the owner’s historical salary draw above a market rate of compensation. The founder, age 65, has a strong two-person management team and three key producers. He would like to “cash out” (i.e., realize the economic value of his life’s work) without “checking out,” by staying involved in the company as a strategic advisor and mentor. He thoroughly researches the advantages and disadvantages of a third-party sale and becomes concerned about the disadvantages discussed above. An advisor recommends considering an ESOP and he hires our firm to perform an ESOP feasibility analysis.

Our feasibility analysis begins with a summary of the owner’s goals which include the following:

- Maximize the value of the stock to be sold

- Reward the employees who helped build the company

- Minimize the impact of taxes on the transaction

- Maintain the company’s independence

- Minimize “execution risk”

“Execution risk” refers to the potential of a company beginning a sales transaction that never closes. Studies indicate that fewer than 30 percent of the companies that begin a sale to an outside third party actually close the deal. Many things can cause a sale to fail, but the bottom line is that in a typical sale, the buyer—not the seller—almost always has all the negotiating power. In most cases, the only leverage the seller has is his or her ability to walk away.

Valuing service firms is based on the free cash flow the company generates. For a service company, free cash flow is earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) or earnings before owner’s compensation (EBOC). Assuming a valuation multiple between 5 times (x) and 8x is applied to free cash flow, the value of a firm with free cash flow of $5 million is in the range of $25 million–$40 million. Obviously, this is a very wide range and determining where a company falls within that range depends on a number of factors including the company’s profit margins (which depend on its business model), operating efficiencies, client demographics (accumulation or decumulation phase), and the transferability of the clients. For purposes of this example, assume that the subject firm is valued by an independent valuation firm at $32.5 million, which assumes an EBIT multiple of 6.5x.

A sale to an ESOP provides a very generous equity-based benefit plan for the firm’s employees in the form of annual allocations of company stock to their ESOP accounts of up to 25 percent of pay. In addition, we establish a management incentive plan (MIP) in the form of stock appreciation rights (SARs) for the firm’s two managers and three key producers. This provides them with significant additional equity-based financial incentives that could double their economic reward as a result of participating in both the ESOP and the MIP.

The founder lives in a state with a high state tax rate and his total tax liability on his sales proceeds will be $9.75 million, which represents 30 percent of the sales price. However, by revoking the company’s Subchapter S election prior to the ESOP sale, he becomes eligible for special tax treatment under IRC §1042, which is available only to owners who sell stock in a Subchapter C Corporation to an ESOP. The company must wait five taxable periods to re-elect Subchapter S tax status and often this has no consequence since the ESOP’s tax deductions eliminate most of the company’s tax liability. Once Subchapter S tax status has been re-elected, the company’s income will not be subject to federal corporate or individual income tax.

Generally having to wait to re-elect S tax status is not an issue for ESOP companies. Most companies prefer Subchapter S status for two reasons: (1) S-corporation income is usually taxed at a lower rate than is C-corporation income; and (2) an S-corporation shareholder usually receives more favorable tax treatment on his sales proceeds when the transaction is structured as an asset sale instead of a stock sale. These S-corporation tax advantages are minimized when a C corporation implements an ESOP. The tax rate differential generally is not material as a result of the large corporate tax deductions generated while the company is retiring the ESOP debt. The two levels of tax on the gain of an asset sale is not a consideration since an ESOP sale is structured as a stock sale. Further, if the company sells to a third party in the future, the purchaser will be buying shares owned by the tax-exempt ESOP trust; therefore, the proceeds from that sale will not be subject to tax.

This transaction serves the dual purpose of providing an ownership succession vehicle and an avenue for management transition. Following the ESOP sale, the owner will continue to serve as the company’s chairman of the board but will resign as CEO. He elevates one of the key managers to that position while the other continues in his role as CFO. Further, since an ESOP is a “friendly buyer,” any potential execution risk is minimized. The ESOP implementation is structured in two distinct phases. In the first phase, the company will engage an institutional trustee specializing in ESOPs and will hire a valuation consultant to establish a range of value for the owner’s stock. The trustee will use this range of value to negotiate the ultimate price and terms of the transaction. If the owner is not satisfied with any of the terms or the sales price, he has the power to “pull the plug” on the deal with a minimal investment of time and money. If the owner finds the price and terms to be acceptable, the second phase of the implementation process begins. During this phase, all of the transaction documents are drafted and reviewed and the business owner is virtually guaranteed that the sale will close with very little risk of anything happening to derail the process.

One of the primary challenges facing an ESOP’s purchase of a service company is the financing of the transaction. Banks evaluate ESOP loans as they would any other commercial loan, by considering the company’s cash flow and collateral. Service firms typically have great cash flow but can be “collaterally challenged.” Here, we identify a bank that has a unique understanding of service companies and is willing to loan the company a sum that equals three times the company’s cash flow, or $15 million, which funds 46.15 percent of the ESOP’s purchase price. The remaining 53.85 percent will be financed using a subordinated seller note.

Some owners initially react negatively to the thought of financing a portion of the purchase price using subordinated promissory notes. However, after learning more about the provisions of the seller notes, they often find this approach to provide many economic benefits. For instance, because seller notes are subordinated debt, holders are entitled to returns typically demanded by mezzanine lenders. This means that a business owner who receives a portion of his ESOP sales proceeds in the form of a seller note could realize a possible pre-tax rate of return of 14–18 percent, consisting of a combination of current interest payments, deferred interest payments, and warrants. The value of the warrants is tied to the company’s underlying stock price, thus providing the seller with a significant future economic benefit that can increase the total value he receives to an amount in excess of the initial sales price. We structure this transaction so that the company will pay both the bank debt and the seller note in full in seven years. However, if the company’s post-ESOP performance exceeds management’s conservative expectations, the company has the ability to prepay the ESOP debt without penalty.

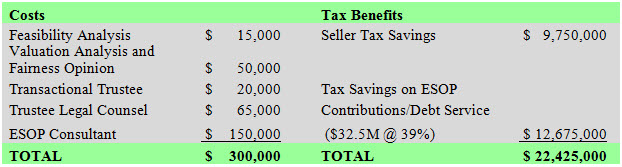

The ESOP feasibility analysis includes a cost-benefit analysis that compares the costs associated with implementing an ESOP to its tax benefits. The following is a sample cost-benefit analysis based on this company and this transaction.

The cost of implementing this ESOP equals 1.34 percent of the ESOP’s tax benefit. Generally, the costs of implementing an ESOP will be in the range of 1.0 and 3.0 percent of the ESOP’s tax benefits.

As mentioned above, an ESOP is not the right answer in every situation. However, an ESOP is extremely attractive to companies possessing the following characteristics:

- A “mature” privately-held company that

- Is profitable

- Has a strong successor management team

- Has little debt

- Has an owner or owner who are considering a liquidity event

- A company with at least $1 million of free cash flow (EBIT or EBOC)

- A company with a strong banking relationship or access to a specialized lender

- An owner who would prefer to transition the company to “insiders,” i.e., key employees and/or family members who are employed by the company.

The first step in the ESOP process is to speak with an ESOP consultant who can answer your preliminary questions and obtain information needed to evaluate whether an ESOP makes sense for you and your company. If so, then you will want the consultant to perform an ESOP feasibility analysis.

Kelly Finnell, JD, CLU, AIF, is president and CEO of Executive Financial Services, Inc. He has published 13 articles on the use of ESOPs in ownership succession planning and is the author of one of the most highly acclaimed books on the subject, The ESOP Coach: Using ESOPs in Ownership Succession Planning. Mr. Finnell graduated from the University of Memphis, magna cum laude, and from the University of Memphis Cecil C. Humphreys School of Law, where he was published in the University of Memphis Law Review, served as chief justice of the Moot Court Board, received the American Jurisprudence Award for Equitable Remedies, was the recipient of the Judge John D. Martin Scholarship, and was named to Who’s Who Among Students in American Universities and Colleges. Mr. Finnell can be reached at (901) 259-7979 or kfin@execfin.com.

Andrew T. Holmes, JD, LLM, is vice president and shareholder of Executive Financial Services, Inc. After receiving a JD from Mississippi College School of Law, he received an LLM in taxation from Washington University in St. Louis School of Law. Mr. Holmes is a member of the Tennessee and Mississippi Bar and recently received a Retirement Plan Fundamentals Certificate from the ASPPA. He co-wrote an article published in the September 2014 issue of Estate Planning, and he is a featured panelist at the National Center for Employee Ownership (NCEO) Annual Employee Ownership Conference in April. Mr. Holmes can be reached at (901) 259-7900 or at aholmes@execfin.com.

Image courtesy of stockimages/FreeDigitalPhotos.net