Taking a Deeper Look into Momentive, Part 1

Secured Creditors Lost Almost $200 Million in Economic Value Due to the Imposition of Below Market Interest Rates

Many bankruptcy practitioners have focused on the recent decisions in Momentive[1] that forced secured creditors to refinance prepetition loans at below market interest rates. Most of these practitioners’ publications focus on the courts’ findings and the potential implication on future matters.

However, three interesting questions are not addressed in most (if any) of these publications:

However, three interesting questions are not addressed in most (if any) of these publications:

- How much economic value was taken from the secured creditors if one believes they should have received the market rate of interest? (Hint: the answer is in the title.)

- Is there a limit to the amount of implied lender’s costs, profits, and fees that should be removed from the market interest rate when determining the cramdown interest rate?

- Could future courts use the same methodology employed in Momentive yet arrive at the market interest rate by making a reasonable change in one or two assumptions?

This part of the article addresses the first two questions. The second part of this article will address the last question.

The Gamble

Any interesting bet from the observer’s perspective has the potential for a large win if the gambler wins and a large loss if the gambler loses. Such a bet was made in Momentive. Our tale concerns a group of secured creditors with various liens ($1.1 billion first lien, $250 million 1.5 lien[2]) and a debtor who tussled over two issues:  make-whole payments and cramdown interest rates.

Make-Whole Payments

Make-whole payments are required in certain situations when a debtor repays a debt before maturity. Debtors typically want to repay debt before maturity when they can refinance at lower interest rates. This refinancing is good for the debtor but often bad for the creditor (absent a make-whole payment) because the creditor will likely receive a lower risk-adjusted return when it reinvests the proceeds. A make-whole payment (when required) compensates the creditor for its economic loss in this situation.

The applicability of make-whole payments becomes more complicated when the debtor files for bankruptcy. On one hand, the debtor did not refinance the loan, which suggests a make-whole payment is not applicable. On the other hand, the end result of a bankruptcy filing can be the refinancing of prepetition debt at lower interest rates, which is what ultimately happened to the aforementioned secured debt in Momentive. A legal analysis of when make-whole payments apply is beyond my capabilities.

Cramdown Interest Rates

Cramdown interest rates refer to the interest rate imposed on a creditor by a judge over the creditor’s objection. The interest rate is essentially crammed down the creditor’s throat in this situation. The cramdown interest rate must compensate the creditor to ensure that the stream of future payments (principal plus interest) has the same “value” as an upfront cash payment equal to the crammed down creditor’s claim.[3]

There is controversy over the definition of “value”. Some believe the crammed down creditor must receive the market interest rate in order to preserve the economic value of its claim. Others believe the market interest rate is too high because it implicitly includes components (i.e., lender’s costs, profits, and fees) that, if included in the cramdown interest rate, would provide a windfall to creditors because they did not arrange a new loan.

The Secured Creditors’ Choices

Secured creditors were presented with two choices:

- Give up their pursuit of an approximate $200 million make-whole payment and get paid the full amount of their secured debt claim ($1.35 billion face) in cash; or

- Continue their pursuit of the make-whole payment and risk having their secured debt claim refinanced by the court at below market interest rates.

The secured creditors decided to roll the dice and continue their pursuit of the make-whole payment. The potential reward was receiving a make-whole payment of approximately $200 million while preserving the economic value of their $1.35 billion secured debt claim, which results in a net payout of approximately $1.55 billion. The risk was not receiving a make-whole payment and being paid with replacement securities that were worth (in hindsight, approximately $200 million) less than their secured debt claim, which results in a net payout in hindsight of approximately $1.15 billion. The middle ground was accepting the debtor’s offer of $1.35 billion in cash.

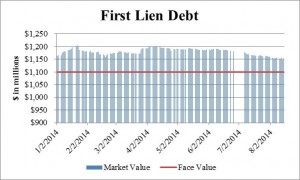

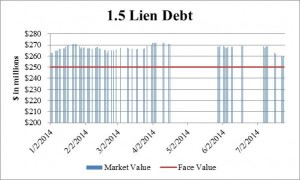

The Market’s Assessment of the Gamble

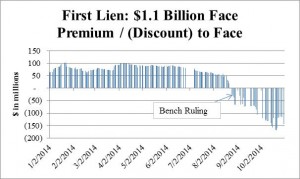

The market value for the secured debt remained well above the face value during the period leading up to the confirmation hearing. See Figure 1, which contains data between January 1, 2014 and the last trading day (August 15, 2014) before the confirmation hearing began on August 18, 2014. Contemporaneous market participants presumably believed that it made sense for the secured creditors to reject the debtor’s offer and pursue the make-whole payment during this time period.

Figure 1[4]

The Outcome

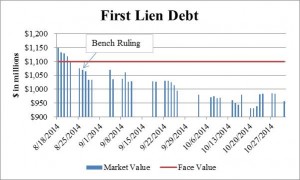

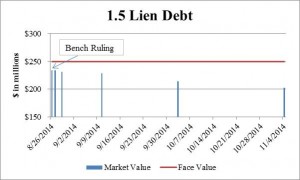

The bankruptcy judge issued his bench ruling on August 26, 2014. The secured creditors lost on both accounts: (a) they did not receive a make-whole payment, and (b) their secured debt claims were to be repaid with replacement securities at below market interest rates. For example, the first lien debt was to be priced as of August 26, 2014 at 4.1% when the market rate (based on the rate in the backup takeout facility)[5] was 5.0%.

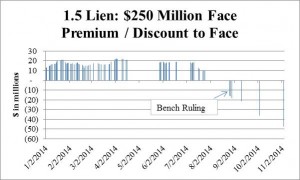

The market value for the secured debt declined substantially during the debtor’s confirmation hearing and continued to decline thereafter. See Figure 2, which contains the market value between the first day of the confirmation hearing and the first date that the replacement securities traded.[6] This data suggests the secured creditors received replacement securities worth far less than their face value.

Figure 2[7]

Expected Net Winnings/Losses from the Gamble Over Time

The difference between market value and face value in Figure 1 and Figure 2 is the expected net winnings or losses from the bet at any particular point in time. This difference over time is shown in Figure 3. Premium to Face in these charts is analogous to “net winnings” whereas Discount to Face in these charts is analogous to “net losses”.

Figure 3[8]

The expected net winnings were sizable for a sustained period prior to the debtor’s confirmation hearing. For example, the average combined (first lien and 1.5 lien) premium during the January 1, 2014 through August 15, 2014 period was approximately $100 million.

The expected net losses deteriorated during the two month period that began with the bankruptcy court’s bench ruling and ended with the first trade of the replacement securities. The combined discount declined from approximately $50 million on the date of the bench ruling to approximately $200 million on the first date that the replacement securities traded.

The Debtor’s Valuation

The debtor had to determine the fair value of the replacement securities in order to arrive at its opening balance sheet for financial reporting purposes. The process for determining a restructured debtor’s opening balance sheet (i.e., when it emerges from bankruptcy) is referred to as fresh start accounting. Fresh start accounting requires the fair valuation of the debtor’s assets and liabilities.

The debtor determined that the fair value for the combined $1.350 billion (face value) of replacement securities was $1.159 billion.[9] The debtor explained, “the fair value of [this] long-term debt was determined based on a market approach utilizing current market yields, and was estimated to be approximately 87% of par value.”[10]

Notably, the debtor’s valuation of the replacement securities is essentially the same as the market’s valuation on the first date these securities traded. The market’s valuation for these securities on that date was $1.1595 billion[11] (versus the debtor’s valuation of $1.159 billion). Moreover, the market’s valuation is not consistent with the debtor’s valuation as of the opening balance sheet date.[12] Thus, it is reasonable to infer that the debtor used (directly or indirectly) the market’s valuation as of the first date the replacement securities traded when it determined the fair value for these securities as of the opening balance sheet date.

Implied Market Yield

The market yield cannot be directly observed. The market yield is inferred from: (a) the promised interest and principal payments, and (b) the market value of the debt security. Market yield is inversely related with market value. Market yield increases as market value decreases. Conversely, market yield decreases as market value increases.

See Figure 4 for the market value and market yield for the first lien debt from the date of the bankruptcy court’s bench ruling through the first date the replacement securities traded.

Figure 4[13]

There are two key takeaways from Figure 4:

- The market yield was approximately 5.0% for a sustained period. This yield is consistent with the 5.0% market interest rate referenced in the bankruptcy court’s opinion.

- The market yield on the first date the replacement securities traded, which the debtor explicitly or implicitly used to value the first lien debt when determining the opening balance sheet, was approximately 6.3%. Thus, the first lien creditors would have received a materially below market interest rate even if the bankruptcy judge used the 5.0% market rate referenced in his opinion.

Implications of Market Yield Being 6.3%, Not 5.0%

Doubling of Economic Value Transfer

There is a material difference between a market yield of 5.0% and 6.3% on the $1.10 billion (face) first lien debt that paid interest at 3.9%.[14] The fair value of the first lien debt is approximtely $1.03 billion at a 5.0% yield and approximately $960 million at a 6.3% yield. Thus, the transfer of economic value from first lien creditors to the debtor is approximately $70 million at a 5.0% yield and approximately $140 million at a 6.3% yield. Said differently, the economic value transfer from first lien creditors to the debtor doubles when the market yield increases from 5.0% to 6.3%.

Any discussion of Momentive that focuses on the 5.0% market interest rate referenced in the bankruptcy court’s opinion (and not the 6.3% yield used by the debtor in its fresh start accounting) ignores half of the economic value transfer from secured creditors to the debtor.

Lender’s Costs, Profits, and Fees

The chasm between the cramdown (3.9%) and market (6.3%) interest rates has an important practial implication too. The judges in Momentive stated that the market interest rate is too high because it includes components (i.e., lender’s costs, profits, and fees) not applicable to the determination of cramdown interest rates for secured claims on corporate debtors.[15]  Implict in these holdings is that the difference between the cramdown and market interest rate may be due to lender’s profits, costs, and fees.[16]

Is there a limit to the amount of lender’s costs, profits, and fees that are baked into a market interest rate? To address this question, we will consider two situations.

August 26

First, consider the cramdown interest rate (4.1%) and market interest rate (5.0%) as of August 26, which is the date that was considered by the bankruptcy judge. At these rates, the replacement securities are worth approximately $1.05 billion, which means the economic value transfer from first lien creditors to the debtor is approximately $50 million in this situation.

It seems difficult to credibly argue that the lender’s costs, profits, and fees were $50 million. The costs (and fees, which are often a mechanism used by lenders to recoup some of their costs) associated with the lender’s sourcing and approval of one loan for $1.1 billion is presumably a very small portion of this $50 million.[17] The lender’s profit is also a very small portion of this $50 million if the economic definition of profit is used.[18] This is an interesting observation because it suggests the adjustment to the market rate should be low.

However, assuming there should be some (i.e., greater than zero but less than $50 million) adjustment for these factors, the judges in Momentive placed the burden on the secured creditors to explain why it should be less than $50 million. The secured creditors did not proffer an adjustment. Thus, the judges in Momentive did not consider the market rate.

October 24

Second, consider what happened between August 26 (the date of the bench ruling) and October 24 (the date the debtor emerged from bankruptcy). The cramdown interest rate declined from 4.1% to 3.9% (presumably due to the decline in the seven year treasury rate that served as the base rate) yet the market yield increased from 5.0% to 6.3%. As mentioned above, the economic value transfer from secured creditors to the debtor is approximately $140 million.

It seems fair to say that there was not a near tripling (from $50 million to $140 million) of lender’s costs, profits, and fees during this two month period. Nevertheless, that is the implicit position taken by anyone who concludes that the difference between the cramdown and market rates as of August 26 and October 24 is solely due to lender’s costs, profits, and fees.

Conclusion

The imposition of below market interest rates on secured creditors in Momentive resulted in a much larger transfer of economic value than is typically reported by practitioners. This result occurs because the market interest rate increased substantially between the plan confirmation hearing and the date the debtor emerged from bankruptcy.

There should be a reasonable limit to the amount of lender’s costs, profits, and fees that are implied in market interest rates. Creditors should put forth analyses that frame this limit when they believe they are in a venue where a below market interest might be imposed on them.

[1] The bankruptcy court’s bench ruling was in August 2014. The bankruptcy court issued a corrected and modified ruling in September 2014. The district court’s opinion was in May 2015.

[2] It is referred to as “1.5 lien” because these claims were behind the first lien notes but senior to the second-lien obligations.

[3] The reference to “value” is contained in section 1129(b)(2)(A)(i)(II) of the Bankruptcy Code.

[4] Market value is inferred from debt prices obtained from Bloomberg Finance L.P. There are fewer observations for the 1.5 lien debt because it traded less frequently than the first lien debt.

[5] The backup takeout facility would be used to finance the payment to the secured creditors if they chose to accept the debtor’s offer of getting paid in cash for their secured debt claim in exchange for giving up their pursuit of the make-whole payment.

[6] The replacement first lien debt began trading on October 31, 2014. The replacement 1.5 lien debt began trading on November 4, 2014.

[7] Market value is inferred from debt prices obtained from Bloomberg Finance L.P.

[8] Calculations are inferred based on data in Figure 2.

[9] Momentive’s 2014 10K at p. 52. http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1405041/000140504115000012/mpm201410-k.htm

[10] Ibid at 51.

[11] The $1.1595 billion is computed as follows: $957.0 million for the first lien debt (as of October 31, 2014) and $202.5 million for the 1.5 lien debt (as of November 4, 2015).

[12] The opening balance sheet was October 24, 2014. The first lien debt traded at over 89% of par value (not 87% as it did on October 31, 2014) and the 1.5 lien did not trade on this date.

[13] Market value is inferred from debt prices obtained from Bloomberg Finance L.P. Market yield is imputed based on a discounted cash flow model I constructed that uses the market values and the contractual terms of the replacement securities. Market value is for the prepetition securities on all dates except for the last date in the chart, which is the first date that the replacement securities traded.

[14] The first lien debt paid interest at 3.88%, not 4.10%, presumably due to the decline in the seven year treasury rate (the base rate used for the cramdown interest rate) between August 26 and the subsequent date when the interest rate was determined.

[15] There is a debate amongst bankruptcy practitioners, and there is split amongst the circuits, on whether the cramdown interest rate should equal the market interest rate for secured claims on corporate debtors. This debate is beyond the scope of this article.

[16] We say “may be due to” instead of “was due to” because the bankruptcy judge indicated that the secured creditor had the burden of proof to establish these amounts. The secured creditors did not present any evidence for these amounts. Thus, no analysis of these factors was performed by the judges.

[17] For example, if we assume the fully burdened costs are $200 thousand per person, it would require an army of 50 employees working solely on this one loan for three months to reach just $2.5 million, or 5.0% of the $50 million. Â This is why the costs of a loan should be referenced in terms of basis points ($2.5 million in expenses on a $1.1 billion loan is 23 basis points), not percentage points ($50 million in expenses on a $1.1 billion loan is 4.55%).

[18] An economic profit is only generated when the expected return on capital is greater than the opportunity cost of capital (i.e., the net present value on the loan). For example, there is no economic profit on a loan that pays interest at 5.0% when the opportunity cost of capital is also 5.0%. Thus, the economic profit is (essentially) zero when it is determined through the actions of contemporaneous market participants competing in an efficient market.

Michael Vitti, CFA, joined Duff & Phelps in 2005. Mr. Vitti is a Managing Director in the Morristown office and is part of the Disputes and Investigations practice. He is also a member of the firm’s Complex Valuation and Bankruptcy Litigation group, focusing on issues related to valuation and solvency. Mr. Vitti has more than 19 years of valuation experience.

Mr. Vitti can be reached at: (973) 775-8250 or by e-mail to: Michael.Vitti@duffandphelps.com.

The author is not an attorney and is not offering legal advice. This article is written from a business valuation practitioner’s perspective who works on, among other things, bankruptcy-related matters.