Why All Values Are Not Created Equal

Understanding Terms and Bridging a Potential Valuation Gap

It is not uncommon for litigation to stem from disagreements over the value of privately held companies and ownership interests in those entities. In those situations, many different values are often discussed as the parties attempt to reach a resolution. It is important to make sure that the parties are speaking the same language as far as the type of value being considered—equity value, enterprise value or invested capital value. While these three types of value are related, there are significant differences between them and understanding those differences is important in reaching a fair resolution. In his article, the author walks through the differences in equity, enterprise, and invested capital value he shares with attorneys and views as additional tools to effectively navigate valuation-related disputes and negotiations.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]Resources:

BV Fundamentals For CPAs And Other Business Advisors, 5-Part Series

10 Common Errors in Valuation and How to Address These Issues

EBITDA Single Period Income Capitalization for Business Valuation

Fast and Powerful Operational Diagnostics Provide Transparency into Enterprise Value

[/su_pullquote]

It is not uncommon for litigation to stem from disagreements over the value of privately held companies and ownership interests in those entities.  In those situations, many different values are often discussed as the parties attempt to reach a resolution.  It is important to make sure that the parties are speaking the same language as far as the type of value being considered—equity value, enterprise value, or invested capital value.  While these three types of value are related, there are significant differences between them and understanding those differences is important in reaching a fair resolution.  In this article, we walk through the differences in equity, enterprise, and invested capital value, and share how this may provide attorneys additional tools to effectively navigate valuation-related disputes and negotiations.

Setting the Stage

Let’s assume we have a dispute in which Party A believes that a company’s value is seven million dollars while Party B believes it is four million dollars. Are the parties really three million dollars apart? We cannot tell based on the numbers alone because they do not tell the entire story—the type of value needs to be defined to give the numbers context.  Therefore, before comparing the different values, we must understand the different types of value that can be determined for a company’s capital structure.

Levels of Capital Structure Value

The three types of capital structure value that are most commonly referenced are equity value, enterprise value, and invested capital value, each of which are discussed in greater detail below:

- Equity Value—Equity value is the value of a company allocable to its equity investors. Equity value is the most commonly-determined value as it represents the value of an investor’s ownership interest in a company.

- Enterprise Value—Enterprise value reflects the following:

Enterprise Value = Equity Value + Debt – Cash

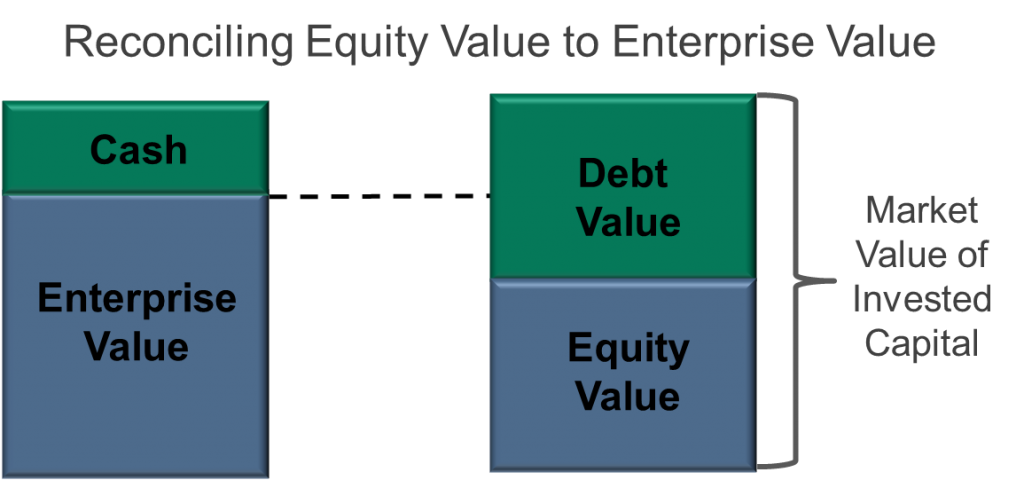

Enterprise value represents the value of a company’s total capital structure (its debt and equity) on a cash-free basis, regardless of the relative percentages of debt and equity. It is also sometimes called a company’s “cash-free, debt-free” value. A company’s enterprise value can easily be converted into an equity value by taking the enterprise value and 1) subtracting its debt; and 2) adding its cash.[1]

Investment bankers often speak in terms of enterprise value because they typically focus on the overall value of the company’s operations (not necessarily its equity value). From their perspective, it is up to potential buyers to determine how much of the purchase price will be funded with debt vs. equity.

Enterprise value is also typically used when determining EBITDA and revenue-based multiples because it removes the impact of how much cash and debt a company is carrying (which are simply financing decisions) in determining the value of the company’s operations.

- Invested Capital Value—Invested capital value reflects the following:

Invested Capital Value = Equity Value + Debt

Invested capital value represents the combined value of a company’s interest-bearing debt and equity.  It is like enterprise value in that interest-bearing debt is added to the company’s equity value, but the company’s cash balance is included in calculating its invested capital value. Therefore, a company’s invested capital value reflects the full value of both its equity and debt.

Reconciling Values

It is critical to understand that while these values measure different components of a company’s capital structure, they are interrelated. This is particularly important if a value is determined at one level and needs to be reconciled or adjusted to another level.

Misunderstandings result because people often talk about values in terms of multiples—“A company in my industry sold for 5x EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization).” However, when a revenue or EBITDA multiple is applied to determine a company’s value, it typically produces an enterprise value (because EBITDA and revenue are before interest expense, so they do not take into account the impact of debt service). Therefore, it is necessary to adjust the enterprise value for the interest-bearing debt and cash balances of the company being valued to arrive at its equity value. Confusing enterprise value with equity value may result in an investor significantly overestimating the value of his or her ownership interest (particularly for companies with meaningful debt balances).

The illustration below shows the relationship between equity value, enterprise value, and invested capital value:

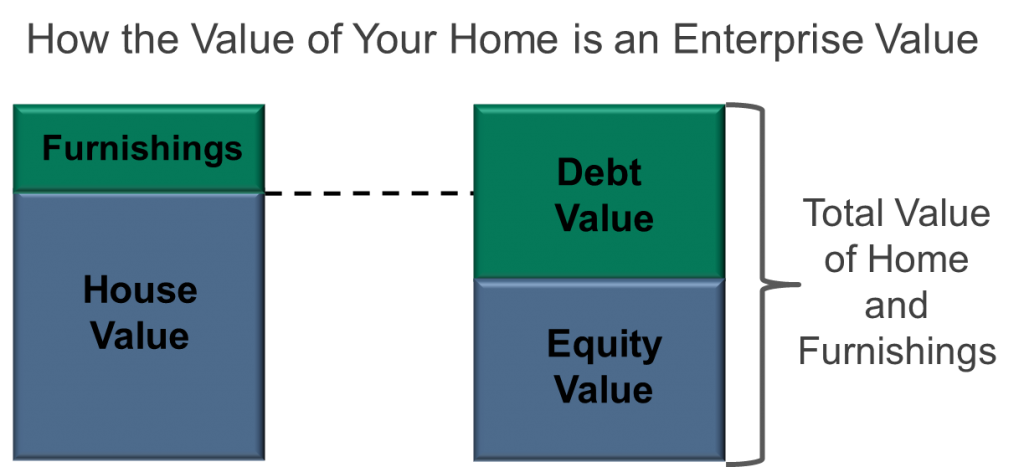

The relationship between a company’s various types of value is like the financing for your home. For example, a company’s enterprise value is just like the value of your home, which is likely financed through some combination of debt and equity, as shown below:

If you were to sell your home, you would not receive the full sale price. Instead, you would receive the net amount remaining after the debt balance was satisfied, which represents your equity in the home (just like the equity value of a company).

Finally, in this example, the value of your home furnishings is just like the company’s cash balance (which generally would not be sold with the home and would instead by retained by the seller). Those furnishings still have value, but that value is not reflected in the selling price of the home itself. You would likely take your furnishings with you in the event of a sale because the new owner would supply their own (just like a company’s cash balance). This makes a company’s invested capital value similar to the value of your home plus all of the furnishings.

Is There Really a Difference in Value?

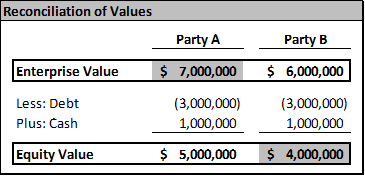

Let’s go back to our dispute scenario and consider some additional facts:

- Party A’s seven million dollar value is an enterprise value based on previous discussions with an investment banker.

- Party B’s four million dollar value is an equity value based on an appraisal prepared by a valuation expert.

- The company has three million dollars in debt and one million dollars in cash.

Based on these additional (and critical) facts, Party A is really indicating that it believes the company’s equity value is five million dollars (only one million dollars higher than Party B’s position). Alternatively, Party B is indicating that it believes the company’s enterprise value is six million dollars (again, only a one million dollars difference from Party A). This reconciliation is shown below:

With the additional context around the values being discussed, the parties only have a one million dollar difference in their perceived value of the company and its equity; not three million dollars. What may have at first appeared to be an unbridgeable gap in value is much closer than the numbers would have suggested without a deeper understanding of just what they meant.

Applicability in M&A Contexts

As discussed earlier, investment bankers often speak in terms of enterprise value rather than equity value. In addition, valuation multiples often provide an indication of a company’s enterprise value, not its equity value. As a result, it is extremely important that both the buyer and seller in a potential business sale understand the transaction prices being discussed. This is particularly important for sellers—it is easy for them to get caught up in the larger enterprise values being discussed and fail to consider the impact of debt in determining the company’s implied equity value (which represents their share of the total transaction proceeds).

Using the figures in the example above, let’s assume that Party A’s investment banker told him that his company is worth seven million dollars. If Party A does not understand that this is an enterprise value, he may be expecting to personally receive seven million dollars from the sale, not the five million dollars that would be netted if the company were to sell at a seven million dollar enterprise value. Party A may then begin evaluating the potential deal based on an amount of expected proceeds (seven million dollars) that is much higher than what he would actually receive (five million dollars). This misunderstanding can create a significant expectation gap for Party A that may be difficult to correct later in the sale process once a number is already in his head.

Conclusion

All values are not created equal—as shown above, a company’s “equity value” can be vastly different from its “enterprise value,” which may differ from its “invested capital value.” Therefore, whenever reviewing or discussing a company’s value, it is important to establish what type of value is being determined. This will greatly reduce the likelihood of miscommunication, making it far more likely that 1) disputes will be resolved as effectively as possible; and 2) the parties involved in M&A transactions will have appropriately managed expectations regarding value and net proceeds from the outset.

This article, previously published September, 2015, is reprinted here with permission from the Cleveland Metropolitan Bar Journal.

[1] It should be noted that A/P, accrued expenses, and other non-debt liabilities are typically not considered part of “interest-bearing debt” for the adjustment from equity value to enterprise value (and vice versa) because these liabilities are part of a company’s net working capital, not its equity/debt capital structure.

Sean R. Saari (Sean) manages Skoda Minotti’s Valuation & Litigation Advisory Services group and is responsible for helping clients address their valuation, litigation support, tax, financial reporting, strategic planning, and business advisory needs. He joined Skoda Minotti over 10 years ago and assists a diverse client base. He has authored more than 75 articles, e-books, blogs, and whitepapers and is a regular speaker, both locally and nationally, on valuation, litigation support, accounting, and tax issues.

Mr. Saari can be contacted at (440) 605-7221 or by e-mail to ssaari@skodaminotti.com.