Practical Advice on Rebutting and/or Defending a Valuation Report

While valuation may generally be part art and part science, rebutting and/or defending a valuation introduces additional types of art and science. The stakes are often higher because interested parties are affected by the contested valuation’s outcome, and the narrative can become more nuanced due to conflicting views on a variety of issues. This article endeavors to cut through the clutter and provide practical tips to address some common themes that arise in rebutting and/or defending a valuation report in a contested situation.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]Resources:

Business Valuation Report Peer Review—Case Analysis in Person (CAP) or by Webinar (CAW)

Report Writing: Review and Analysis

Business Valuation Reporting and Challenges in the Litigation Environment

Rebuttal Reports and the Defense Expert’s Role

[/su_pullquote]

Introduction/Executive Summary

While valuation may generally be part art and part science, rebutting and/or defending a valuation introduces additional types of art and science. The stakes are often higher because interested parties are affected by the contested valuation’s outcome, and the narrative can become more nuanced due to conflicting views on a variety of issues. This article endeavors to cut through the clutter and provide practical tips to address some common themes that arise in rebutting and/or defending a valuation report in a contested situation.

Keep it Simple, Stupid

Whether one wants to refer to it as the acronym we learned as kids (KISS), or by a more official-sounding name such as Occam’s Razor, the point is the same: a problem solver should focus on limiting the number of contested assumptions. The simpler approach is often (but not always) the best approach. That sometimes gets lost in a “battle of the experts,” especially when the focus is on esoteric issues that do not ultimately have a meaningful effect on the conclusion.

It is useful to identify all the differences between conflicting valuations and quantify the impact of each issue. It is also useful to combine the impact of related issues (e.g., control premium and marketability discount when valuing a controlling interest) to identify the net impact of related issues. The output is a list of (related) issues ranked from largest to smallest impact, which can be used to identify the main points of contention.

The context for the valuation also matters. It is much easier to keep it simple when addressing a binary issue (such as solvency in a preference lawsuit) than a dispute where every one dollar of difference matters. For valuation disputes that address a binary issue, one often only needs a few contested issues to break in his favor. For example, it does not matter if the value of a business’ assets is one million dollars or $100 million higher than its liabilities in a valuation dispute related to a preference matter because they both result in a solvency (assets > liabilities) determination.

Cumulative Effect of Biases

The metaphor “death by a thousand cuts” describes how many small issues can eventually combine into a very large outcome. This process can play out in contested valuations as well.

There are many decisions that can flow into a valuation. The Guideline Company Approach alone requires decisions such as:

- Which guideline companies to use?

- Which metric(s) for multiples (e.g., revenue, EBITDA, EBIT, etc.) to use?

- Which period(s) (e.g., three-year average, two-year average, last fiscal year, last twelve months, next fiscal year, etc.) to use?

- Which of the computed multiples (low, first quartile, median, mean, third quartile, max, regression-based, judgment-based, etc.) to use?

- Should a control premium be added? If yes, how much?

- Should a marketability discount be deducted? If yes, how much?

- Are there nonoperating assets that should be added? If yes, how much?

- Are there nonoperating liabilities that should be deducted? If yes, how much?

- If other valuation approaches (e.g., Guideline Transaction or Income) are used, how much weight should be given the to the Guideline Company Approach?

The long list of decisions means a valuation practitioner can arrive at a very biased result without having to use materially biased assumptions. Instead, the consistent use of small biased assumptions, when most go in the same direction, can cumulatively result in a very biased result.

Identify Unsupportable Internal Inconsistencies

There is no rule that says a valuation practitioner must be consistent all the time. For example, a valuation practitioner may say a valuation approach (e.g., Market or Income) is reliable in some situations but not reliable in other situations. Similarly, a valuation practitioner may say the use of a multiple (e.g., Enterprise Value/Revenue) is relevant in some situations but not others. There is nothing inherently wrong when a valuation practitioner’s position boils down to “it depends” on the circumstances. To the contrary, a valuation practitioner’s ability to adapt to the needs of the situation (assuming the valuation practitioner is not being flexible for result-driven reasons) is a virtue, not a vice.

However, flexibility should only go so far. There are some situations where inconsistency cannot be rationally explained. An opposing expert or attorney should identify these situations when reviewing a valuation report.

One such example is the reliability of guideline companies. This is often a binary issue: the guideline companies are typically either reliable (i.e., reasonably comparable to the subject company and have reliable data) or they are not. Nevertheless, it is possible for a valuation practitioner to take a more nuanced view.

For example, a valuation practitioner may say the Guideline Company Approach cannot be reliably executed because the guideline companies are not reasonably comparable enough to the subject company. This same valuation practitioner may also say the guideline companies are reasonably comparable enough to the subject company to use their information (e.g., capital structure and beta) to arrive at a cost of capital estimate for the subject company. The approach to the binary issue (ability to reliably use the guideline companies) is internally inconsistent in this situation.

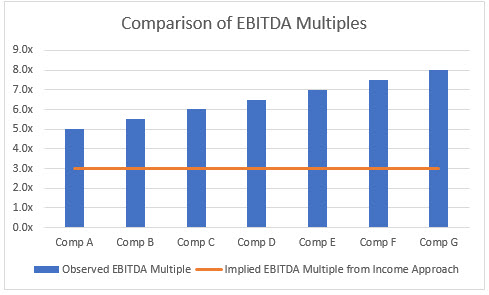

An opposing expert or attorney may argue that the internal inconsistency is result-driven. For example, assume the valuation practitioner concluded on an Income Approach with an implied Enterprise Value/EBITDA multiple of 3.0x whereas all the guideline companies traded substantially higher than 3.0x EBITDA, which is shown in Figure 1. While not definitive, this fact pattern may suggest that the valuation practitioner determined the Guideline Company Approach could not be used for result-driven reasons because (a) choosing even the lowest observed multiple would result in a significantly higher value via the Guideline Company Approach and (b) it is hard to credibly argue the guideline companies are reasonably comparable to the subject company for cost of capital-related purposes but not for market multiple-related purposes.

Identify Extreme Implied Assumptions

Sometimes a valuation practitioner relies on an extreme assumption but arguably “hides the ball” by redirecting the focus somewhere else. An opposing expert/attorney should identify these situations to refocus the debate.

For example, consider use of the company specific risk premium. Some may believe it is a vital adjustment needed to arrive at a reliable conclusion. Others may think of it as a “fudge factor” used to arrive at a predetermined (lower) valuation. A discussion on the validity of the company specific risk premium concept is beyond the scope of this article. However, it is possible to refocus the company specific risk premium’s implicit effect on another underlying assumption, which is within the scope of this article.

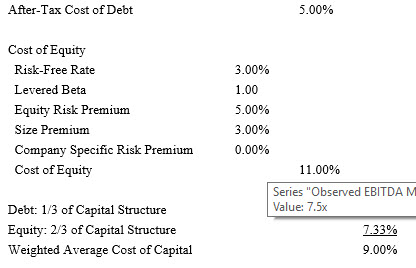

Assume a valuation practitioner arrived at a 9.0% WACC prior to consideration of a company specific risk premium. See Figure 2 for a set of assumptions that would arrive at that conclusion.

Figure 2 (No Company Specific Risk Premium)

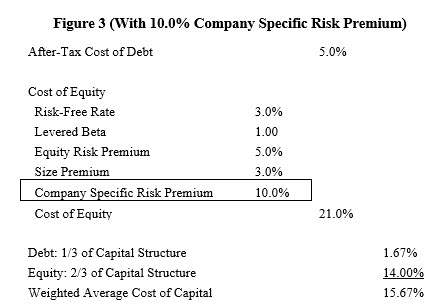

Further assume this valuation practitioner added a 10.0% company specific risk premium to the computations in Figure 2. As shown in Figure 3, this increases the WACC by almost 75%, from 9.00% to 15.67%. This change has a massive effect on valuation.

Figure 3 (With 10.0% Company Specific Risk Premium)

Â

Â

It can be difficult to support, and argue against, a company specific risk premium. The company specific risk premium is often based on the valuation practitioner’s (reasoned) judgment if one takes a glass half full perspective, or the valuation practitioner’s ipse dixit (i.e., say so) if one takes a glass half empty perspective. In either event, there is often no benchmark that can be reliably used to assess whether the 10.0% company specific risk premium is appropriate.

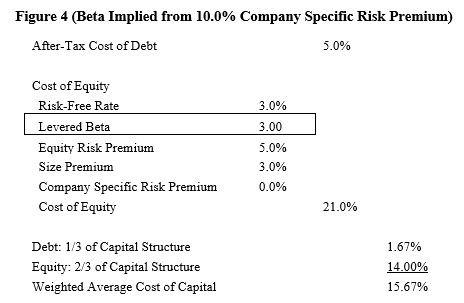

Nevertheless, that should not stop an opposing valuation practitioner/attorney from highlighting the extreme implications of a 10.0% company specific risk premium. This can be done by removing the 10.0% company specific risk premium from Figure 3 and solving for the beta that is needed to arrive at the 21.0% cost of equity (and 15.67% WACC) that was determined with the 10.0% company specific risk premium, while keeping the other assumptions constant. As shown in Figures 3 and 4, the beta increases by 200%, from 1.0 to 3.0.

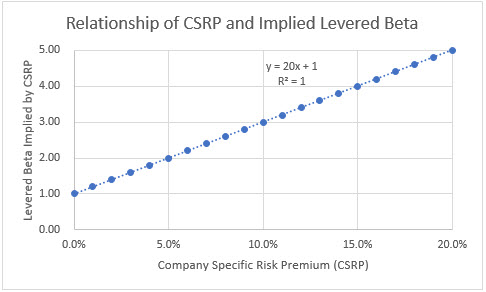

The relationship between Figures 3 and 4 is clear: the implied levered beta increases by 0.2 for every one percentage point increase in the company specific risk premium. Figure 5 contains a sensitivity analysis that confirms this relationship. The y-intercept is 1.0 because the levered beta is 1.0 when the company specific risk premium is 0.0%. The implied levered beta increases to 2.0 when the company specific risk premium is 5.0%, to 3.0 when the company specific risk premium is 10.0%, to 4.0 when the company specific risk premium is 15.0%, and so on.Â

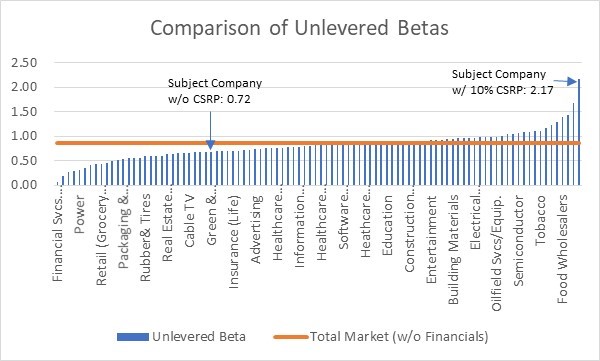

To benchmark the implied levered betas, we can delever them (based on the 1/3 debt and 2/3 equity capital structure) and compare them to unlevered betas across industries. The unlevered beta in the no company specific risk premium scenario (levered beta of 1.0) is 0.72. The implied unlevered beta in the 10% company specific risk premium scenario (levered beta of 3.0) is 2.17. We can compare these unlevered betas to the most recent (last updated 1/5/18) industry average unlevered betas identified by Professor Damodaran[1],[2] (or from another source and/or for another period). As shown in Figure 6, the unlevered beta without the company specific risk premium of 0.72 is below the total market (without financials) of 0.87[3] and the implied unlevered beta from the scenario with the 10.0% company specific risk premium of 2.17 is higher than the average unlevered beta for all 94 industries in Professor Damodaran’s data set. That is a massive shift in the subject company’s risk relative to other industries.

The comparison in Figure 6 does not necessarily mean that the 10.0% company specific risk premium is unsupportable. However, it does demonstrate the implications of this assumption: the subject company had a below market average (without financials) unlevered beta before inclusion of the company specific risk premium and it implicitly had a higher unlevered beta than every industry after inclusion of the company specific risk premium. Any rebuttal of the 10.0% company specific risk premium should address this observation.

Identify False Conservatism

It is not unusual for a practitioner to say he was conservative because he could/should have arrived at a lower (or higher) value, which would be consistent with his client’s interests, but he chose not to do so. This approach can suggest that the valuation is not influenced by the client’s interests.

Sometimes this is false conservatism because the valuation practitioner may have been conservative on some issues, but aggressive on other issues. This can result in the valuation not being conservative, and perhaps being aggressive. These types of debates often occur in contested valuations and are relatively straight forward.

The most interesting type of false conservatism occurs when someone uses conservatism to conceal illogical results, which impeaches the reliability of the approach. One example I have seen dealt with multiple events in an event study.

An event study identifies the effect of a disclosure to estimate the value of a stock in a “but for” world where the disclosure was made as of an earlier date. For example, if the stock traded at $100 and the event study shows a negative 10.0% effect, the value of the stock in the “but for” world is $100 * (1-10.0%), which equals $90.

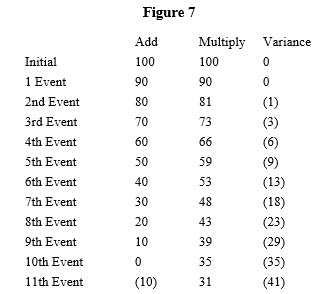

In this instance, which used the event study framework in a retrospective valuation-related context, the interesting debate (which sets aside many nuanced issues regarding how to deal with each event) was over how to combine multiple events. For example, if there were two events of 10.0% each, should they be added or multiplied? Adding results in a 20.0% reduction: $100 * (1 – (10.0% + 10.0%)) = $80. Multiplying results in a 19.0% reduction: $100 * (1-10.0%) * (1-10.0%) = $81.  The valuation practitioner acknowledged that event studies typically multiply, but he believed it made more sense to add. He added in this instance.

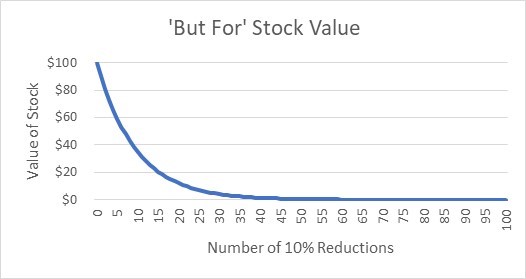

Where it gets interesting is what happens when there are many 10.0% events. As shown in Figure 7, the variance increases as additional events are added. Notably, the stock price becomes negative by the 11th event. This cannot happen in the real world, as stock prices are never lower than zero due to limited liability, so they trade at option value when the underlying asset value is less than liabilities. To avoid a negative stock value, which is clearly wrong, this expert “conservatively” stopped including events before the value became negative.

The data in Figure 8 is based on multiplying the results. This outcome is consistent with the real world, as the adjusted stock price never becomes negative, even if 100, 1,000, or an infinite number of 10.0% decline events are included into the analysis.

Figure 8

The data in Figures 7 and 8 demonstrate, in this author’s opinion, why stopping with fewer than ten events with 10.0% declines while using the “addition” approach to combining events is false conservatism.

Conclusion

Valuations are often based on a series of decisions. Reasonable people can disagree over how to arrive at some of these decisions, which are often judgment calls.

However, some judgment calls are harder to defend/easier to attack than others. It goes without saying that preparers of direct reports should try to minimize the number of hard to defend judgment calls whereas preparers of rebuttal reports should highlight an opposing expert’s hard to defend judgment calls when they occur.

[1] http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/Betas.html

[2] The same approach to unlevering betas and effective marginal tax rate (24.0%) is used for the subject company and industry average unlevered betas. 24.0% is the default marginal tax rate in Professor Damodaran’s model.

[3]The total market beta (which includes financials) is 0.69.

Michael Vitti, CFA, joined Duff & Phelps in 2005. Mr. Vitti is a Managing Director in the Morristown office and is part of the Disputes and Investigations practice. He is also a member of the firm’s Complex Valuation and Bankruptcy Litigation group, focusing on issues related to valuation and solvency. Mr. Vitti has 20 years of valuation experience.

Mr. Vitti can be contacted at (973) 775-8250 or by e-mail to michael.vitti@duffandphelps.com.