Common Sense, Simplicity, and

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 H.R.1

There was a flurry of activity within the valuation community following passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) and several complicated tax calculation models were unveiled. While we acknowledge the TCJA is beginning to show a noticeable impact on the level of our value conclusions, how much of an impact ought it really have on the way we perform our work? In this article, the author reviews salient features of the TCJA and concludes with some thoughts and suggestions for retaining common sense and applying simplicity to a highly complex valuation.

Signed into law on December 22, 2017 and effective January 1, 2018, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) is the first overhaul of the U.S. tax code since the Tax Reform Act of 1986.

As would be expected, there was a flurry of activity within the valuation community (and other communities) to determine the effects of the Act on our work. The requisite seminars have been trotted forth, and complicated tax calculation models proposed. But, while we acknowledge the TCJA is beginning to show a noticeable impact on the level of our value conclusions, how much of an impact ought it really have on the way we perform our work?

We asked this question about a year ago in The Value Examiner and continue to ask it in this article. The answer should help us apply common sense to the time and effort spent on addressing the TCJA in our analyses. We are still concerned that the proposed approaches to the TCJA cause confusion, rather than clarity, and will necessitate backtracking in a year or two.

To bring this concern into vivid focus, we begin with an important history of U.S. taxation, prepared for our paper in The Value Examiner. We then review salient features of the Act and conclude with some thoughts and suggestions for retaining common sense and applying simplicity to a highly complex situation.

U.S. Income Taxation—A Historical Perspective

To provide a context for our further discussion of TCJA effects, we focus on one aspect of the history of the U.S. taxation—the income tax. As the reader will see, these data demonstrate the high level of uncertainty and change related to tax regimes, suggesting the need for generalized models of tax effects rather than granular ones.

Tax Data Comparability and Consistency—From the IRS Point of View

The IRS issued a data release titled “Corporate Income Tax Brackets and Rates 1909–2002”[1] that provides some useful insights into the comparability and consistency of tax data over time. We paraphrase the following:

- Income brackets are not comparable over time because the definition of “income” has altered from year to year. Changes in tax law, accounting practices, and the economy, as well as taxpayers who exhibit ever-growing sophistication at tax avoidance, make comparability impossible.

- Various kinds of tax gaming result from the tension between the corporate and individual income tax because corporations are ultimately owned by individuals who seek to avoid being taxed twice on the same income. Tax gaming obscures both comparability and consistency.

- The existence of many different types of corporate legal entities, from ordinary for-profit to a variety of non-profits, creates a wide divergence among tax rules. Such rules change and shift regularly.

- There have been numbers of different tax regimes for corporations that own each other or are subject to the same ownership/control, as well as other types of legal entities.

- Tax credits, deductions, and additions interact with each other and other features of the tax system. Thus, “it is not even possible to estimate what tax rates would be if they were taken into account.” (p. 285)

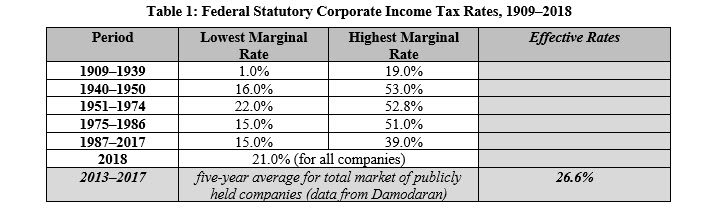

Federal Corporate Income Tax Data

Table 1 provides Federal statutory corporate income tax rates from 1909–2018. To simplify the data, we group years into time periods based on what looked like major shifts to marginal rates at either the upper or lower end or both. We only list the lowest and highest marginal rates for each time period.[2]

Note that while Table 1 shows only major changes in marginal rates, rates actually changed in one way or another approximately thirty-two times from 1909 through 2018 (or, approximately once every three years for 109 years).

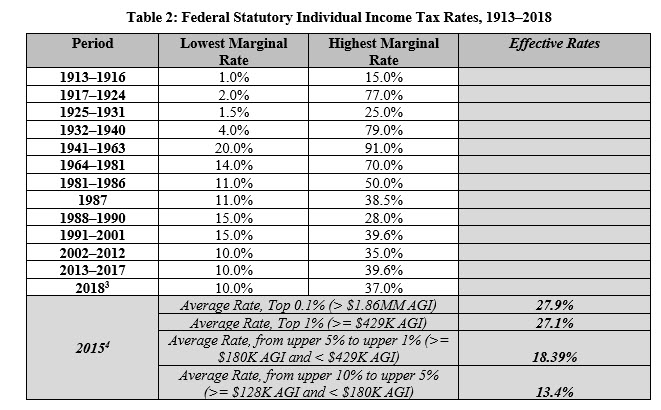

Federal Individual Income Tax Data

Table 2 provides data on Federal statutory individual income tax rates from 1913–2013, obtained from The Tax Foundation. Again, to simplify the data, we grouped years into time periods based on what looked like major shifts to marginal rates at either the upper or lower end or both. We provide rates for the most common category, “Married Filing Jointly”, only.

Note that while Table 2 shows only major changes in marginal rates, rates changed in one way or another approximately thirty-one times from 1913 through 2018 (or, approximately once every three years for 105 years).

Besides This…

Along with shifting income tax rates, the types and levels of other taxes as well as overarching tax rules, regulations, and interpretations shift. These generate corresponding updates to accounting rules and ongoing legal precedent. They also have produced that infamous publication of some 70,000 pages in length, the Internal Revenue Code (IRC).

“[A]s published by companies like Thomson Reuters and CCH, [the IRC] takes up a little over 4,000 pages…[It] includes all past tax statutes, not just current laws…The 70,000 [page] number [includes] IRS regulations and revenue rulings (~6,350 more pages) and, most importantly, case law covering court proceedings surrounding the tax code.”[5]

And Then, There are the Taxpayers

If tax regimes are massive, complex, and changeable, the responses of taxpayers to these regimes are even more so. Each entity, investor, and individual brings strategies, interests, expectations, and shifting tax attributes to the task of optimizing their positions within tax regimes. And, their actions and interactions are dynamic, not linear and static.

Clearly, the only way to hope to model all these moving parts is to generalize. But, how? Before we can answer this, we will briefly review the TCJA rule changes that are most directly relevant to valuation.

The TCJA

Introductory Comments

In his January 12, 2018 blog post, “Musings on Markets: Taxing Questions on Value”, Dr. Aswath Damodaran writes:

Without mincing words, the U.S. corporate tax code, as it existed in 2017, was an abomination…I was therefore predisposed to favoring tax reform and Congress delivered its version towards the end of 2017. While the process was messy and partisan, it represents the most significant change in corporate taxation in the United States in my lifetime, and as with all tax reform, it is a mix of the good, the bad, and the ugly, with your political priors determining which one you believe dominates. No matter what you think about the tax reform package, there is the one thing that is not debatable: it will impact equity value and affect corporate behavior in the coming year.[6]

Duff & Phelps (D&P), in its Q1 2018 Valuation Insights: Special Tax Reform Issue, further states:

The Act will require management and valuation analysts to revisit their financial projections to ensure that they properly reflect (1) the direct impacts of changes in the tax law; (2) any changes in capital investment strategy driven by changes in the tax law; and (3) any changes in projected revenue and expenses resulting from changes in the economy that may be spurred by potential increases in economic activity, at least over the near-term.[7]

Damodaran provides two caveats that should be kept top-of-mind as we incorporate TCJA effects into our work: (1) most of the key TCJA rule changes have been available for investor review for over a year before the Act was finalized. Thus, at least some of the Act’s anticipated effects are already baked into current prices. (2) Companies will respond to the TCJA in a dynamic, not static, manner. This creates uncertainty regarding future corporate (and individual) investing, financing, and dividend behavior.

Rule Changes of Note for Valuation Analysts

- Substantial drop in corporate statutory income tax rate: The corporate statutory Federal income tax rate drops from 35% to 21%.

- New limitation on the percent of interest expense deductible for tax purposes: For companies above $25 million in gross revenues, interest expense deductions are capped at 30% of “adjusted taxable income” (defined as EBITDA through 2022 and EBIT after that). Non-deductible interest expense (over the 30% threshold) can be carried forward indefinitely.

- Immediate expensing of investments in “qualified property” and related effects on depreciation: The immediate 100% expensing (i.e., depreciation) of purchased “qualified property” (tangibles, etc.) makes these assets fully tax-deductible in the year of purchase. This rule change, to be phased out from 2023–2027, applies to new and used property and to qualified assets acquired in both M&A transactions and business combinations.

- Tax treatment of R&D costs: Beginning in 2022, R&D expenses (including software development) occurring in the U.S. must be capitalized and amortized over five years, rather than expensed. If these expenses occur outside the U.S., they must be amortized over 15 years.

- Tax treatment of net operating losses: The TCJA limits net operating loss carryforwards (NOLs) to 80% of taxable income in each year. Unlike the pre-Act Code, these NOLs can be carried forward indefinitely. In addition, there are no changes to pre-Act NOLs or Section 382 limitation rules.

- Replacement of a global tax model with a regional one: The U.S. global tax model is replaced by a regional one in which U.S. companies will be required to only pay foreign taxes on foreign income. In addition, while having to pay a one-time tax to repatriate cash trapped in foreign locales, companies are now free to bring their money back when they choose. In addition, the TCJA imposes a tax on excess profits earned in foreign subsidiaries, dis-incenting companies from putting profit-generating intangibles in foreign tax havens.

- Tax treatment of pass-through entities (PTEs): Under the TCJA, active and passive ownership in PTEs are taxed differently, as are non-professional service and professional-service PTEs. The following, direct from Congress, gives a more detailed view of PTE provisions in the Act.

…a portion of net income distributed by a pass-through entity to an owner or shareholder may be treated as “business income” subject to a maximum rate of 25%, instead of ordinary individual income tax rates. The remaining portion of net business income would be treated as compensation and continue to be subject to ordinary individual income tax rates.

Each owner or shareholder would separately determine their proportion of business income. Net income derived from a passive business activity would be treated entirely as business income and fully eligible for the 25% maximum rate. Owners or shareholders receiving net income derived from an active business activity (including any wages received) would determine their business income by reference to their “capital percentage” of the net income from such activities.

Under the provision, owners or shareholders generally may elect to apply a capital percentage of % to the net business income derived from active business activities to determine their business income eligible for the 25% rate. That determination would leave the remaining % subject to ordinary individual income tax rates…

…Under the provision, the default capital percentage for certain personal services businesses (e.g., businesses involving the performance of services in the fields of law, accounting, consulting, engineering, financial services, or performing arts) would be zero percent. As a result, a taxpayer that actively participates in such a business generally would not be eligible for the 25% rate on business income with respect to such personal service business. However, the provision would allow the same election to owners of personal services businesses to use an alternative capital percentage based on the business’s capital investments. This election would be subject to certain limitations. The provision would also apply a maximum 25% rate on certain dividends from a real estate investment trust (REIT) and patronage dividends from cooperatives.[8]

So…these rule changes hardly encourage simplified valuation modeling. How can we represent this level of complexity in models that also remain flexible for future changes and transparent enough to explain to clients and triers of fact?

Use Common Sense: Keep it as Simple as Possible

FWIW

Many of the great contributions to economics and finance involve abstraction of highly complex, dynamic fact patterns into simple, elegant equations that allow us to make useful conclusions at a 40,000-foot level. In fact, we valuation professionals do this all the time but rarely think about it. Abstraction and simplification make it possible to do our work and communicate well with our clients.

While simplicity and common sense do not always feel as dazzling as complicated models, here are some ways we can apply them to the situation at hand.

Cost of Capital Estimates

The effect of the decreased deductibility of interest expense on the cost of capital can be explained as follows: (1) business risk increases to the extent business activities are financed by debt capital; (2) however, the deductibility of interest expense (i.e., the tax shield) partially mitigates this risk by lowering the true cost of debt; (3) the TCJA 30% cap on interest expense deductions reduces the tax shield on debt, revealing the true cost of debt and increasing business risk; (4) this, in turn, increases levered equity cost of capital estimates and the WACC. Do we make deliberate adjustments to our cost of capital estimates for the TCJA interest expense effect?

Pre-TCJA standard practice: Our profession deploys numbers of models to estimate the cost of capital. In each, we identify and use public market data for the risk-free rate and measures of market and industry risk. Using various criteria, we then develop and include a measure of company-specific risk. If a WACC is needed, we estimate a cost of debt and a capital structure for the subject using industry or company benchmarks. We iterate the WACC accordingly.

Post-TCJA suggested: Keep following standard practice. Use market data thoughtfully but do not adjust it for the TCJA. We are not more prescient than the markets themselves.

Remember that market data already has ingested and digested about one hundred years of changes to tax regimes and investor responses. During 2017, the markets were already ingesting and digesting the effects of the TCJA, before it officially became law. This process will continue.

Likewise, market costs of new debt will shift over time. Companies may deleverage since the TCJA limits the deductibility of interest expense. These actions will all show up in the market data we use.

Forecasting Net Income and Net Cash Flow

As stated earlier in this article, D&P indicates that we are going to need to properly reflect the following TCJA effects in our forecasts of net income and net cash flow:[9]

- The direct impacts of changes in the tax law;

- Any changes in capital investment strategy driven by changes in the tax law;

- Any changes in projected revenue and expenses resulting from changes in the economy that may be spurred by potential increases in economic activity, at least over the near-term.

Here are several (non-exhaustive) examples of how we might accomplish this.

Direct Impacts: Limitation on the Deductibility of Interest Expense

Pre-TCJA standard practice: We currently prepare an amortization table for each outstanding debt instrument. We then pull annual interest expense directly from these tables into our forecasting models.

Post-TCJA suggested: Create an intermediary schedule from which calculated deductible interest expense and the re-calculated tax shield can be pulled into the forecasting model. This schedule can also track non-deductible (carryforward) interest expense amounts.

Be careful to remember how this rule change affects actual cash flow. The subject company will continue to pay out the full interest expense in cash. But when taxes are calculated, a more limited cash tax shield is now available. Your forecasting model needs to reflect this two-tiered cash reality.

Direct Impacts: Immediate Expensing of Investments in Qualified Property

Pre-TCJA standard practice: We currently prepare depreciation schedules for: a) capitalized tangible assets already on the balance sheet at the valuation date; and b) tangible assets management anticipates buying during the forecast period. These depreciation totals flow directly into our forecasting models.

Post-TCJA suggested: Since qualified assets purchased from January 1, 2018 on will be immediately expensed in full, there is no need to create separate depreciation schedules for them. We can continue to use already-created depreciation schedules for tangible assets in place at December 31, 2017 until these assets are fully depreciated.

Direct Impacts: Limitation on Net Operating Loss Carryforwards

Pre-TCJA standard practice: We currently apply NOLs to 100% of the taxable income in a given year. If NOLs exceed the taxable income in that year, we carry forward the remaining NOL amount into as many future years’ taxable income as needed to use up this amount.

Post-TCJA suggested: Again, create an intermediate schedule that calculates and tracks allowable NOLs and subsequent NOL carry-forward amounts. Apply NOLs to forecasted annual taxable income from this schedule.

Indirect Impacts: Changes in Capital Investment Strategy and Changes in the Post-TCJA Economy

Pre-TCJA standard practice: As valuators, we consult with management to understand the subject’s capital investment strategy before we model it and/or assess the model given us by management. As this strategy changes, we seek further information from management and change our model accordingly. Ordinarily, we are not asked to develop the strategy itself, though we may choose to offer comments regarding the one presented to us.

In addition, we are responsible to consult with management before, during, and after we model the subject’s future revenue and expense to ensure we are representing the subject accurately. Ordinarily, we are not asked to develop the baseline Year One forecast (i.e., budget), since that is management’s task. Whomever develops the forecasts, part of our work is to research the economy and industry in order to understand their influence on future firm performance.

Post-TCJA suggested: Take the time to understand the nuances of the TCJA that may affect the subject’s capital investment strategy and industry as well as the general economy. Follow standard practice by continuing to seek management inputs and adjusting the model accordingly. Check results with management for reasonableness.

Tax Modeling for C-Corporations

Pre-TCJA standard practice: When we model taxes for historical or forecasted normalized taxable C-corporation income, do we try to capture every influence on the subject’s tax situation? No. We simplify. We pick either the corporate marginal rate du jour or some historical measure of the corporate effective rate and use this for both the historical period of examination and the forecast period/terminal period.

Is it then reasonable or necessary to build granular models of taxation, going ten or more years out into the unknown, to incorporate TCJA sunset provisions and other uncertainties? Probably not. Things are going to change anyway, and we are likely to be wrong with our granular estimates.

Post-TCJA suggested: Continue following standard practice and simplify, with the explicit understanding that the continued pace of change and a monstrous level of complexity require it.

Tax Modeling for Pass-Through Entities (PTEs)

Pre-TCJA standard practice: When we model taxes for historical or forecasted normalized taxable PTE income, do we consider all aspects of each specific owner’s tax facts and circumstances? No. We simplify. We pick either the top individual marginal rate at the time or some historical measure of the individual effective rate and use this for both the historical period of examination and the forecast period/terminal period.

Again, we acknowledge this is a broad-brush approach, but the only reasonable one to manage so much complexity and so many unknowns.

Is it then any more reasonable or necessary to build detailed models of specific owner tax facts and circumstances in order to incorporate the nuances of the new TCJA tax breaks and requirements? Is it even possible to get so granular with PTE owner taxes? Probably not.

Post-TCJA suggested: Continue following standard practice and simplify where possible. One simplification might be to assume that all owners in an operating PTE will be taxed in the same way and split the tax model into two tracks, one for each TCJA rate.

A Common-Sense Suggestion re the Forecast Period

In our profession, extending the forecast period out 10 to 15 years has become in vogue. Naturally, this also requires modeling the many sunset provisions of the TCJA.

We suggest that, unless the subject company’s situation or industry requires an extended forecast period, there is neither need nor defensible rationale for a forecast period that is longer than five years. No one, even management, can reasonably expect to quantify the future beyond a five-year horizon.

Exceptions to this would be companies in biotech or pharma and companies that anticipate a dramatic change in facts and circumstances in years six or seven.

Conclusion

Tax laws come and never really go. They just get absorbed, layered up, and diffused by the economy, the markets, the accounting profession, and the courts. Company and individual responses to tax laws are complex and dynamic. Response trends are easiest to find looking back, not forward. Yet, valuation focuses on the future.

What is the most prudent thing to do as the TCJA rolls in and its effects spread?

First, take time to understand the details of the Act. Then, continue to follow standard practice and do thoughtful work. Avoid getting entangled in excess modeling. It can create confusion and generate results that will prove to be flawed over time. Simplify and take the long view.

Apply common sense.

This article contains excerpts from Maintaining Perspective on the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 H.R.1, The Value Examiner, September/October 2018.

—

Sarah B. von Helfenstein, MBA, CVA, is the founder and CEO of Value Analytics & Design, One Broadway, 14th Floor, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142. Ms. von Helfenstein is a more than 30-year veteran of the start-up wars and has created, launched, and managed numbers of new initiatives. For the past 25 years, she has held a variety of positions within the financial valuation sector. She has spent the last 12 years as a practicing business appraiser. Ms. von Helfenstein has published and presented academic papers on valuation, theoretical finance, economics, and real options in the U.S. and internationally. She has also authored valuation courses and exams, developed valuation curricula and conferences, and edited several key valuation books.

Ms. Von Helfenstein can be contacted at (617) 401-1122 or by e-mail to svonhelf@valueanalyticsanddesign.com.

[1] https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/02corate.pdf

[2] https://corporatetax.procon.org/view.resources.php?resourceID=005129

[3] https://www.forbes.com/sites/robertberger/2017/12/17/the-new-2018-federal-income-tax-brackets-rates/#36367aa9292a

[4] November 2015 Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact Bulletin, “Summary of the Latest Federal Income Tax Data, 2015 Update”. This data was derived from the Internal Revenue Service.

[5] https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/3/29/15109214/tax-code-page-count-complexity-simplification-reform-ways-means

[6] http://aswathdamodaran.blogspot.com/2018/01/january-2018-data-update-3-taxing.html

[7] Q1 2018 Valuation Insights: Special Tax Reform Issue, Duff & Phelps. p. 4.

[8] U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means. Tax Cuts and Jobs Act H.R. 1, “Section by Section Summary: Section 1004. Maximum rate on business income of individuals”. p. 4.

[9] Paraphrased from Q1 2018 Valuation Insights: Special Tax Reform Issue. Duff & Phelps.