COVID-19

Highlights the “Good” and “Bad” Hindsight Debate

Many predictions are doomed to fail whereas hindsight is undefeated. Predicting the future is very difficult due to the countless permutations that can occur. By contrast, anyone can observe what happened after the fact. Not surprisingly, it can be tempting to focus on the reliability of hindsight over the (typically) more relevant contemporaneous projections when performing assessments as of a prior date. This article addresses the “good” vs. “bad” hindsight debate within the context of COVID-19 and its implications to other matters.

Introduction/Summary

Many predictions are doomed to fail whereas hindsight is undefeated. Predicting the future is very difficult due to the countless permutations that can occur. By contrast, anyone can observe what happened after the fact. Not surprisingly, it can be tempting to focus on the reliability of hindsight over the (typically) more relevant contemporaneous projections when performing assessments as of a prior date. This article addresses the “good” vs. “bad” hindsight debate within the context of COVID-19 and its implications to other matters.

Current Date vs. Prior Date Assessments

Hindsight is not available in current date assessments. Absent access to a time machine, we do not know what happened (past tense) tomorrow, next week, or next year when we perform an assessment as of today. Thus, hindsight is not a topic to address for current date assessments.

Conversely, hindsight is always available in assessments as of a prior date. We know what happened between the assessment date and today. Thus, hindsight is a topic that can affect all assessments as of a prior date.

Should Hindsight Be Allowed?

The applicability of hindsight is an interesting debate.

On the one hand, no hindsight should be allowed. Hindsight is never used—because it is not available—in current date assessments. Why should assessments as of a prior date be performed on a different basis than current date assessments? Many will say they wear “hindsight blinders” to avoid even the appearance of using hindsight when performing analyses as of a prior date.

On the other hand, some hindsight should be allowed. Hindsight can identify issues that were knowable or address certain important issues as of the prior date. Shouldn’t this relevant information be incorporated into the analysis as of the prior date? Many will say they only use hindsight to confirm what was known or knowable as of the assessment date.

As a practical matter, there can be a lot of grey area when assessing hindsight. Some may see a clear case of confirming what was known or knowable as of the earlier assessment date. Others may see a blatant attempt at data mining to support a pre-determined position. The debate ultimately results in the identification of “good” (i.e., relevant for the prior date assessment) and “bad” (i.e., not relevant for the prior date assessment and potentially misleading) aspects of hindsight.

How Does COVID-19 Factor in this Discussion?

COVID-19 is a global pandemic that is causing massive disruption. Businesses are losing immense amounts of sales. The U.S. unemployment rate recently swung from a 50-year low to the highest level since the Great Depression. The financial condition and outlook for most companies clearly changed a lot over a short period of time.

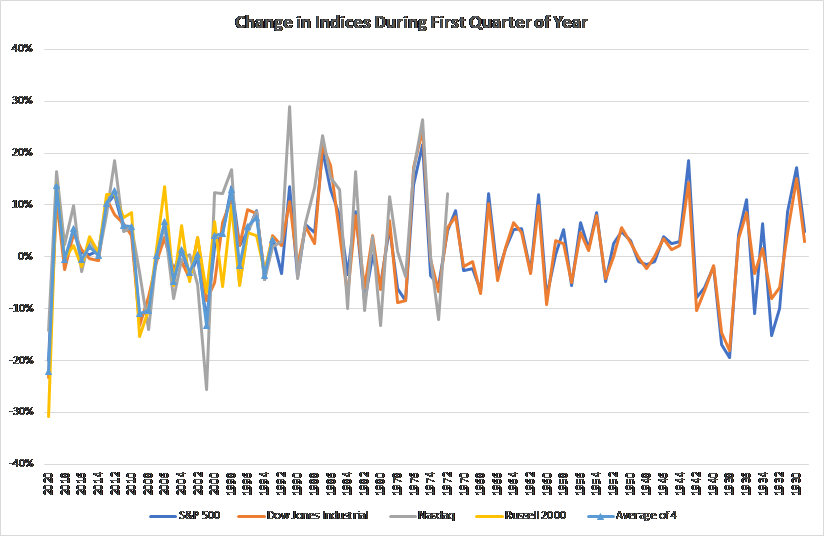

The decline in the value of U.S. equities during the first quarter of 2020, as shown in Figure 1, was unprecedented. It was the worst first quarter on record, with the S&P 500 declining by 20% and the Dow Jones Industrial Average declining by 23%.

Figure 1

Source: Data per Capital IQ.

This rapid negative change in financial condition during Q1 2020 begs the question: Were the consequences of COVID-19 foreseeable as of earlier dates? After all, the “19” in COVID-19 refers to 2019. Some may argue that financial losses observed in 2020 confirms what was known or knowable about this global pandemic caused by a virus that started in 2019. Others will counter the financial losses that ultimately occurred are much larger than were expected as of earlier dates. It seems likely that some practitioners will engage in a debate over what was known or should have been known as of earlier assessment dates.

Practitioners who believe what happened during Q1 2020 confirms what was known or knowable will highlight factors in the public domain that suggest massive disruption from a global pandemic were imminent. One can imagine a mosaic of information that can be strung together to paint this picture.

Practitioners who believe what happened during Q1 2020 was not foreseeable will presumably highlight two factors. First, contemporaneous market participants did not appear to foresee the consequences of the global pandemic, as evidenced by the all-time highs that occurred for the major stock indices during the middle of Q1 2020. Second, even if the consequences of the global pandemic were foreseeable to some for arguments’ sake, they may not have been foreseeable to everybody. For example, if these consequences were foreseeable by an epidemiologist with access to very specific information, they may not have been foreseeable to, say, a valuation practitioner, which may be the relevant standard for purposes of the analysis that is being performed.

It may be very difficult for a practitioner to persuasively argue the general negative effects of the pandemic were known or knowable as of, say, December 31, 2019 or January 31, 2020. A practitioner making this argument will likely have to make a compelling case for why the markets were (very) materially inefficient on a semi-strong basis.

Is Government Intervention a Factor to Consider?

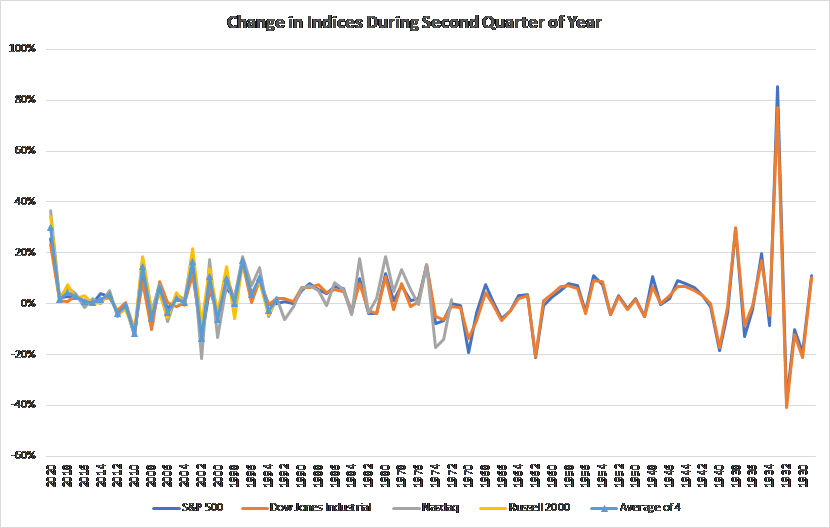

It is important to recognize that decision makers are not potted plants as people react to changes in circumstances. Unprecedented levels of government support were provided to mitigate the economic harm from the unprecedented government-led shutdown in response to COVID-19. This support is presumably a key driver of the large rebound in stock prices that occurred during the second quarter. As shown in Figure 2, the second quarter increase during 2020 was the highest since the 1930s. Any advocate for using the hindsight in Figure 1 (assuming this hindsight should be used for arguments’ sake) will be challenged to explain why the mitigating hindsight in Figure 2 should not also be used.

Figure 2

Source: Data per Capital IQ.

What is the Net Effect of COVID-19 and Government Mitigation?

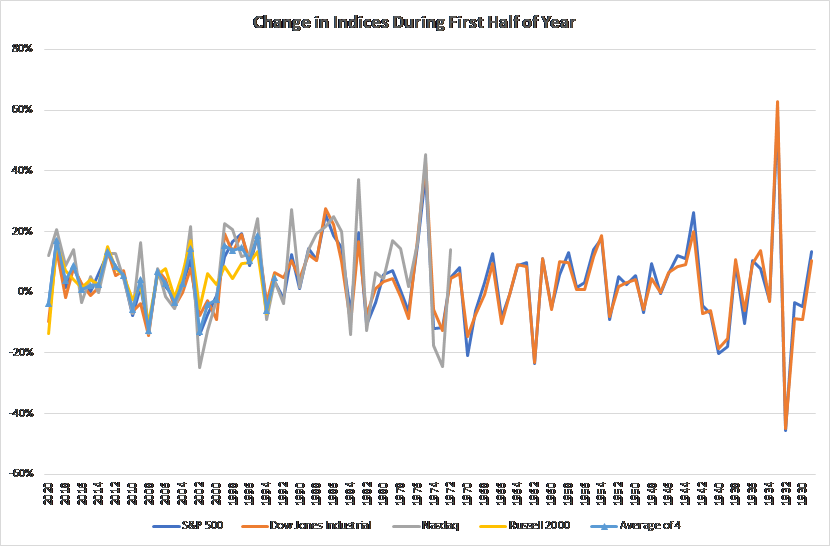

The net effect of the harm (mostly in the first quarter) and mitigants (mostly in the second quarter) is a modest decline in values when measured by major equity indices. As shown in Figure 3, the S&P 500 declined 4%, the Dow Jones Industrial Average declined 10%, and the Russel 2000 declined 14% during the first half of 2020. Notably, the Nasdaq increased by 12% during this same time period. The average change in these four indices is a 4% decline. There have been several years with larger declines during the first half of the year (e.g., 2008 and 2002). Thus, even if one gets past the hurdle of arguing that the pandemic was foreseeable, the net effect of the pandemic-related adjustment may be low.

Figure 3

Source: Data per Capital IQ.

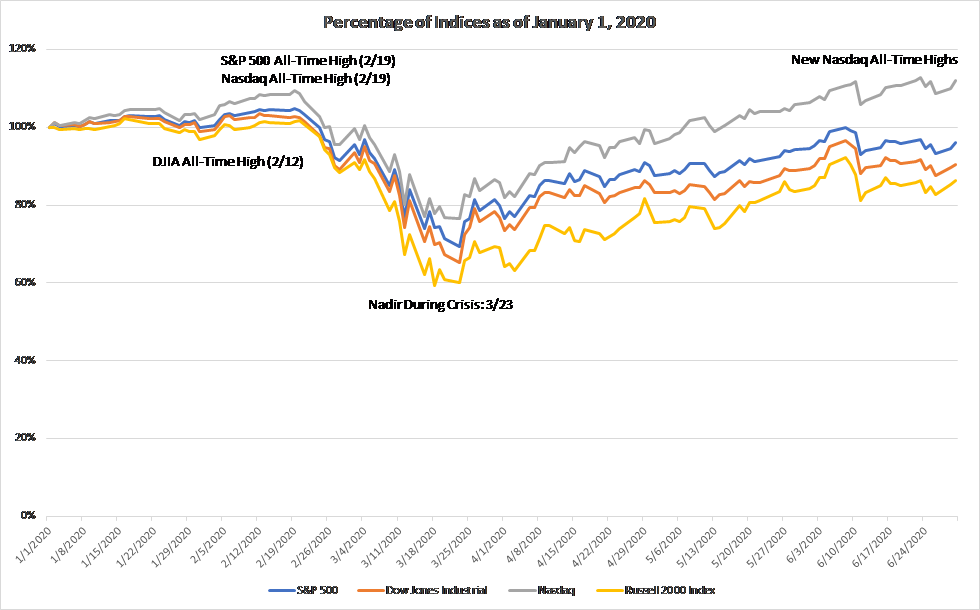

For another way to frame the data, we can also observe the change in indices over the first half of 2020. It is generally V-shaped as the large and swift decline was followed by an increase that was almost as large and swift. See Figure 4.

Figure 4

Source: Data per Capital IQ

Is There Wide Dispersion Within the Data?

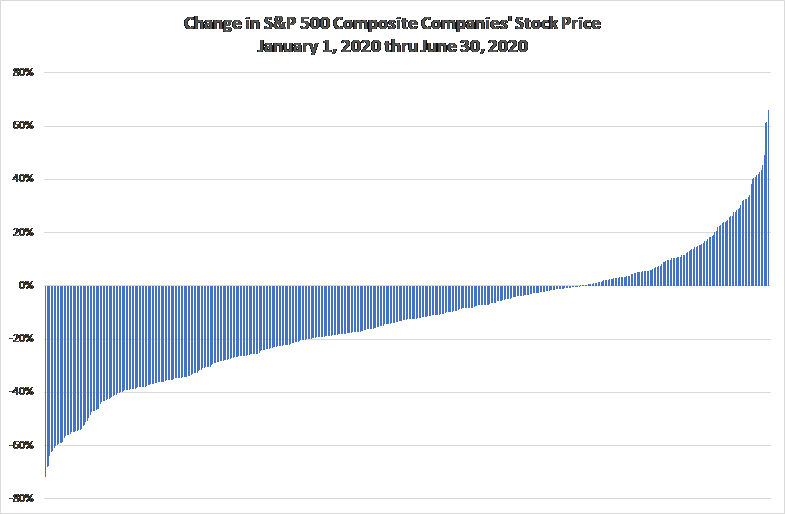

Not surprisingly, a global pandemic and government-led shutdown has resulted in a wide range of outcomes. As shown in Figure 5, many companies within the S&P 500 have experienced a decline of over 50% while some companies have experienced an increase of over 50% in their stock prices during the first half of 2020. The largest declines include cruise- and energy-related businesses, which makes sense given the relative decline in their outlooks. Logically, the largest increases include companies that greatly benefit from people being home-bound, such as Netflix, Amazon, eBay, and PayPal.

Figure 5

Source: Data per Capital IQ

The wide dispersion in data suggests a larger decline in value for the “average” company than the relatively small decline in major stock indices suggests. For example, the median decline within the S&P 500 (almost 13%) is over 3x greater than the decline in the overall index (4%). This observation highlights that the change in an index is not always indicative of the change in individual companies because larger companies have an outsized effect on indices. Extrapolating this concept, the decline in value of the average public company that is not in major indices, or of companies that are not publicly traded, may be larger than the 13% median decline of companies within the S&P 500. A proponent of using hindsight to lower values as of, say, December 31, 2019, will likely focus on the underlying companies within indices, not the overall indices.

So, What Does This All Mean?

Some companies have suffered massive losses because of the global pandemic. The key question is whether these losses confirm what was known or knowable as of earlier assessment dates.

Some companies clearly have a much larger “pandemic beta” (i.e., they are more affected by a pandemic) than others. For example, it seems clear that travel-dependent companies are much more adversely affected than companies that provide essential products or services. It also seems fair to say that some companies have a negative “pandemic beta” because they will be able to profit from the opportunities provided by the pandemic. Thus, the fact that some companies have very different changes in values may be due to different “pandemic betas,” not necessarily confirming what was known or knowable as of earlier dates.

A good example of fortunes changing quickly, and not confirming what was known or knowable as of earlier dates, is the preference lawsuit related to American Classic Voyages. The debtor in this matter made an alleged preference payment (paid a third-party creditor within 90 days of a bankruptcy when the debtor was insolvent) in August 2001 and filed for bankruptcy in October 2001. In between these two dates was the terrorist attacks of 9/11, which had an outsized effect on travel-dependent businesses, such as this cruise company. The bankruptcy court held (and was affirmed upon appeal) that the debtor was not insolvent in August 2001 and by implication the bankruptcy that occurred after the terrorist attacks of 9/11 did not confirm what was known or knowable about a month before 9/11.

Going in the other direction, just because there is a global pandemic, it does not necessarily follow that the pandemic is the cause of a company’s need to file for bankruptcy. Many companies in industries such as retail that filed for bankruptcy during the first half of 2020 would have filed even if there was no pandemic. For others, the pandemic may have been the proverbial “straw that broke the camel’s back” as bankruptcy was highly likely regardless of the pandemic. One cannot credibly claim all outcomes that occurred during the first half of 2020 were pandemic-related hindsight that was not foreseeable as of earlier assessment dates.

Examples of “good” hindsight within the context of COVID-19 may be based on capital raisings. “Good” hindsight occurs when theories can be reliably tested after the fact. For example, in VFB v. Campbell Soup Company, the plaintiff argued contemporaneous stock prices had to be ignored because the market was not fully informed of certain information on the assessment date. The market was clearly informed of this information as of a later date and the company was solvent based on market prices of its securities at this time. Importantly, the overall market and company-specific conditions declined between these two dates, so if this company was solvent as of the later (hindsight) date, it had to be (even more) solvent as of the earlier assessment date. This is an example of “good” hindsight. A company that raises deeply subordinated capital under reasonable terms during a pandemic will likely be able to compellingly argue that it was (more) solvent as of dates that shortly preceded the pandemic.

Assuming hindsight can be broadly used for argument’ sake, the main hindsight-related lesson from COVID-19 may be that if one is going to use relevant hindsight, one should probably use all of it. It may be very difficult to credibly cherry (pit) pick the bad (e.g., the decline during the first quarter of 2020) and ignore the good (e.g., increase during the second quarter of 2020 on the back of mitigation efforts).

Michael Vitti, CFA, joined Duff & Phelps in 2005. Mr. Vitti is a managing director in the Morristown, NJ office and is a member of the Disputes Consulting practice. He focuses on issues related to valuation and credit analyses across a variety of contested matters and industries. This article represents the views of the author and is not the official position of Duff & Phelps, LLC.

Mr. Vitti can be contacted at (973) 775-8250 or by e-mail to michael.vitti@duffandphelps.com.