Understanding Accounts Receivable

The Ratios and Use of Comparative Analysis

Accounts receivable are such an important asset class that company management will be anxious to convert these to cash as soon as possible so that the company is not “overinvested” in its accounts receivable. Accounts receivable ratios are essential analytical and planning tools. There are various analytical tools that can be used by management to compare performance to prior periods and to peer statistics to continuously monitor collections and ensure that customers are adhering to the mutually agreed-upon contractual terms. This article presents the various ratios used to assess the health of accounts receivables and how the ratios can be used for comparison purposes.

Introduction

We often hear a respected businessperson say that “cash flow is the lifeblood of a company’s financial health”. While this is true, there is a corollary to that quote that we should infer, which is that “accounts receivable are the lifeblood of a company’s cash flow.” And, in turn, sales of products and/or services create those accounts receivable. Many, if not most, commercial enterprises that do not predominately transact their business with customers in cash, cannot generate cash flow until they first generate accounts receivable in exchange for transferring products and/or services to their customers or clients. And, in turn, those cannot be generated until and unless products and/or services have been sold.

An account receivable is a monetary amount legally owed by a buyer to a seller that represents an unconditional right on the part of the seller to receive the agreed-upon consideration from the buyer within an agreed-upon period. There is not necessarily a legal document evidencing an account receivable because it arises from a sales transaction that may have been orally agreed upon by the parties or because the transaction was executed in accordance with customary trade terms for the industry or industries in which the parties operate.

Accounts receivable are customarily presented in a classified balance sheet[1] as current assets unless the repayment due date exceeds one year. Should that be the case, only the portion of the accounts receivable that is due one year from the balance sheet date is classified as a current asset with the remainder classified as long-term.

How Receivables Originate

Generally, there is a bilateral sales agreement between seller and buyer as to their respective responsibilities. The agreement can be evidenced by a purchase order originated by the buyer and accepted by the seller, by a formal sales contract negotiated between the buyer and seller, or as previously discussed, under implied customary trade terms that are standard for a particular type of business.

Once an agreement between the parties has been reached, the seller has the responsibility to transfer control of the contracted-for products to the buyer or perform the contracted-for services on behalf of the buyer. Once the seller has performed all or a portion of its obligations, the seller is entitled to issue a sales invoice to the buyer in an agreed-upon amount based on the agreed-upon price.

Some contracts permit partial billings, referred to as “progress billings” based upon the achievement of mutually agreed-upon milestones. Thus, as a sales transaction is being fulfilled by the seller over a period, the seller may be entitled to receive partial payments to help defray the seller’s costs of fulfilling its obligations to the buyer. Some contracts may even require that the buyer submit, in cash, a deposit in advance of any performance by the seller.

A receivable may be due upon presentation of the invoice (immediately) or may provide for various other payment terms such as:

- Net amount of invoice due 30 days from invoice date (referred to as “net 30”)

- Two percent discount if paid within 10 days from invoice date with the full amount of the invoice due if paid after 10 days and within 30 days from the invoice date (referred to as “2/10/net 30”)

- Assessment of late fees and/or interest for invoices not paid within the agreed-upon time period

Collectability Considerations

A business that carries accounts receivable balances must take precautions to ensure that these balances are collectible when due since failure to accomplish this can result in the business suffering credit losses when receivables that were expected to be collected end up becoming worthless. The most important way to mitigate credit losses is to perform thorough credit checks before accepting the first order from a new customer. If a prospective customer has less-than-stellar credit, the company may take measures to protect itself from credit losses by:

- Requiring payment in full by the buyer prior to transferring control of products or performance of services

- Setting payment terms of cash-on-delivery (COD) whereby, the seller is paid concurrently with the transfer of control of the products or performance of the services

- Requiring collateral for the receivable in the form of a security interest in the products sold

- In the construction industry, filing mechanics liens for unpaid amounts that would prevent the buyer from obtaining or transferring legal title to the real estate until the unpaid amounts are paid in full

Even after conducting due diligence on the creditworthiness of new customers, inevitably some customers will default on their obligations and refuse to pay them in full. To acknowledge this reality, receivables are presented on the balance sheet at their “net realizable value” which is defined as the amount that the company management expects to collect. This is accomplished by reducing the amount of accounts receivable stated on the balance sheet by an allowance for credit losses (sometimes referred to as an “allowance for bad debts” or an “allowance for doubtful accounts”).

The computation of the allowance for credit losses requires management to exercise judgment based on its assessment of the status of the current accounts receivable, reference to experience with historical losses incurred, and consideration of the existing economic conditions at the balance sheet date and forecasts of how those conditions could change in the near term.

Analytical Ratios Derived from Accounts Receivable

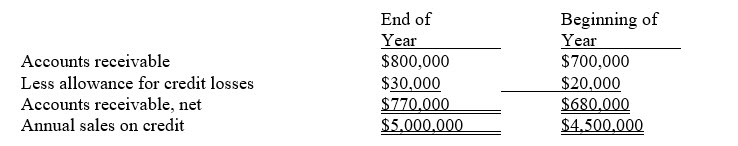

There are several ways to analyze a company’s accounts receivable to evaluate how effectively a company is managing this vital asset. For illustrative purposes, assume that a company’s financial statements present the following numbers:

[1] A classified balance sheet is one in which assets and liabilities are separated into current portions and long-term portions. In general, a current asset is an asset that is expected to become cash within one year from the balance sheet date and a current liability is a liability that is expected to be paid within one year from the balance sheet date.

Based on these reported metrics, here are some examples accompanied by explanations:

Number of Days’ Sales in Ending Accounts Receivable

Annual Credit Sales / 365 Days in the Year = Sales per Day

$5,000,000/365 = $13,699

Accounts Receivable / Sales per Day = Number of Days’ Sales in Accounts Receivable

$770,000 / $13,699 = 56.2 Days Sales in Receivables

This would not be a healthy number of days sales in receivables if the customary terms for the company’s receivables are net 30 days from invoice date since this result would mean that, on average, the receivables are 26.2 days delinquent. This would cause the analyst to question whether the $30,000 allowance for credit losses (which represents 3.75% of the gross receivables balance) is sufficient.

It is always helpful to monitor trends, so a comparison of the current year result should be compared to the prior year result, as follows:

Annual Credit Sales / 365 Days in the Year = Sales per Day

$4,500,000/365 = $12,329

Accounts Receivable / Sales per Day = Number of Days’ Sales in Accounts Receivable

$680,000 / $12,329 = 55.2 Days Sales in Receivables

Note that the days sales in receivables has deteriorated by one day between the first year and the current year increasing from 55.2 days to 56.2 days.

If the company being analyzed is financed by a line of credit that is collateralized all or in part by the receivables, this may also mean that the company’s borrowing capacity may be diminished because most lenders do not include delinquent receivables as eligible collateral.

Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio

Annual Credit Sales / Average Accounts Receivable Balance

Average Accounts Receivable Balance = ($770,000 + $680,000)/2 = $725,000

Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio = $5,000,000 / $725,000 = 6.9 Times

The larger this number, the faster the company is at collecting its receivables. This means that, over the course of a year, receivables are collected 6.9 times. Just as is the case with the prior ratio, this should be monitored over time. In addition, where industry-standard benchmark information is available, the company’s results should be compared to its peer group to see if it outperforms or underperforms its peers.

Accounts Receivable as a Percentage of Credit Sales

Accounts Receivable / Annual Credit Sales

$770,000 / $5,000,000 = 15.4%

This means that at the fiscal year end, 15.4% of annual sales remains uncollected. Obviously, this ratio is related to the Number of Days’ Sales in Ending Receivables.

Comparative Analysis

Ratio analysis is a commonly used tool in financial analysis. Therefore, computing the above-mentioned analytical ratios for accounts receivable is sometimes step one of two steps—a prelude to a process whereby those ratios could be compared to other comparable companies, to divisions within the subject company, and/or to the same company’s prior year or years’ ratios.

Ratio analysis allows the analyst to compare the subject company (and/or divisions within the subject company) to companies in the same industry. It is useful to compare a subject company’s ratios to other years, other companies, and/or industry benchmarks, provided the years and/or companies analyzed are reasonably comparable to the subject company.

Care needs to be taken when drawing inferences from the year on year, division on division, and/or industry benchmark analysis. This comparative analysis is a useful device for determining and examining trends and/or planning.

Comparative analyses could be performed by comparing the above-discussed ratios to industry ratios that may be available from public databases. Examples of those include the Almanac of Business and Industrial Financial Ratios (www.cch.ca), BizMiner (www.bizminer.com), IRS Corporate Financial Ratios and IRS-CALC (www.saibooks.com), and The Risk Management Association (RMA) Annual Statement Studies® (www.rmahq.org/annual-statement-studies/).

These publications obtain their data from financial statements provided to member banks by loan customers and/or gathered data industry-by-industry using North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes and/or Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes. The NAICS is a classification of business establishments by type of economic activity used by government and business in Canada, Mexico, and the USA that has largely replaced the older (SIC) system, except in some government agencies, such as the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Conclusion

Accounts receivable are such an important asset class that company management will be anxious to convert these to cash as soon as possible so that the company is not “overinvested” in its accounts receivable. Accounts receivable ratios are essential analytical and planning tools. There are various analytical tools that can be used by management to compare performance to prior periods and to peer statistics to continuously monitor collections and ensure that customers are adhering to the mutually agreed-upon contractual terms.

This article was previously published in Financial Poise, May 14, 2021, and is republished here by permission.

Ralph Nach, CVA, has more than 40 years of experience in the accounting profession in a variety of capacities, including: audit partner, quality control director, and external peer reviewer. He has also served as a partner in the National Office of Accounting and Auditing of the fifth largest international accounting firm, the U.S. Chief Learning Officer for American Express Tax and Business Services, Inc., an adjunct lecturer in accounting, finance, and economics at Northwestern University, and, for a 10-year stint, the co-author of the annual updates to the popular accounting handbook entitled “Wiley GAAP: Interpretation and Application of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles”. He is a Certified Public Accountant, and, in his current capacity, he serves as a technical quality control consultant, pre-issuance financial statement reviewer, a consulting expert on fraud and forensic matters and as the author, instructional designer, and instructor of the popular “Accounting and Auditing Clinic”™ that is presented throughout the U.S. for scores of CPA firms and thousands of attendees.

Mr. Nach can be contacted at (847) 372-6805 or by e-mail to rnach@epsteinnach.com.

Michael D. Pakter, CPA, CGMA, CVA, CFE, CIRA, CA, CDBV, CFF, MFF, has more than 40 years of experience in forensic accounting, investigations, and litigation services in numerous industries and diverse engagements, including more than 20 years of experience in economic damages and business valuations. State, Federal and Bankruptcy Courts, as well as arbitrators, have recognized him as an expert in forensic accounting, economic damages, business valuation, CPA malpractice, and bankruptcy core proceedings. He is a Certified Public Accountant with multiple additional certifications in economic damages, financial forensics, business valuation, and bankruptcy core proceedings. He focuses his professional practice on forensic accounting, lost profits, lost earnings and other economic damages, business interruption, fraud/financial investigations, bankruptcy core proceedings, and litigation support.

Mr. Pakter can be contacted at (312) 229-1720 or by e-mail to mpakter@litcpa.com.