The Role of Forensic Accountants

in Detecting Fraud in Business Interruption Claims (Part I of II)

Business interruption claims are generally closely scrutinized by insurance carriers and can range from thousands of dollars to claims exceeding $100 million. Insurance carriers often seek the assistance of either internal or external forensic accountants to analyze such claims. During their analysis, forensic accountants often detect the possibility of fraud in a claim, prompting further investigation by the carrier. This two-part article details the role forensic accountants play in identifying and analyzing fraud in business interruption claims and explains the considerations by insurance carriers when hiring external accountants.

Introduction

Business interruption claims are generally closely scrutinized by insurance carriers and can range from thousands of dollars to claims exceeding $100 million. Insurance carriers often seek the assistance of either internal or external forensic accountants to analyze such claims. During their analysis, forensic accountants often detect the possibility of fraud in a claim, prompting further investigation by the carrier.

This two-part article details the role forensic accountants play in identifying and analyzing fraud in business interruption claims and explains the considerations by insurance carriers when hiring external accountants. It offers step-by-step guidance for forensic accountants who are brought on to these complex engagements by insurers.

This discussion begins by defining some of the terms and potential players in business interruption claims that are examined for fraud. First, what is a business interruption? Generally, a business interruption occurs when a specific event (examples include: fires, floods, explosions, hurricanes, tornados, and pandemics) causes a negative financial impact to the operations of a business over some period.

Second, what is forensic accounting and what does a forensic accountant do? The AICPA (the governing body of professional accountancy in the United States) defines forensic accounting as “…the application of specialized knowledge and investigative skills possessed by CPAs to collect, analyze, and evaluate evidential matter, and to interpret and communicate findings in the courtroom, boardroom or other legal or administrative venue.”[1] Therefore, professional accountants, mostly CPAs, conduct forensic accounting engagements. A subcategory of forensic accounting is fraud examination, which may be conducted by either accountants or nonaccountants.

Third, what is fraud? According to Black’s Law Dictionary, fraud is “a knowing misrepresentation of the truth or concealment of a material fact to induce another to act to his or her detriment.” The four major elements of fraud are: (1) false statement of a (2) material fact which is (3) willfully made with an (4) intent to deceive.

While fraud may not be present in every business interruption claim, it is more often discovered in claims examined by forensic accountants who are both experienced and knowledgeable in fraud detection. The ACFE reported in its 2020 Global Study on Occupational Fraud and Abuse, Report to the Nations, that fraud is a global problem affecting all organizations worldwide. The 2020 study, covering 2,504 cases from 125 countries, found fraud caused total losses exceeding $3.6 billion USD.[2] The same study estimated that organizations lose five percent of their revenue each year to fraud.[3]

Business Interruption Claims

A business interruption is the loss sustained by a business or entity due to incidents beyond their control which result in the inability to carry out business functions. Such losses may trigger business interruption coverage through various policies with the entity’s insurance carrier and can be defined as the “necessary interruption of business caused by loss, damage, or destruction by perils insured against real and personal property[4].”

The relevant policy defines the actual coverage, loss calculation methods, and limits of coverage for business interruption claims. But generally, the insured loss is calculated by one of the following three methods:

- The actual loss of business income consisting of net income and continuing normal operating expenses;

- Lost revenues less non-continuing expenses; or

- “Should have been profit” less actual profit.

Each of these methods are addressed in greater detail later in this discussion.

Financial Statement Analysis

The first step in preparing a business interruption claim is the analysis of the insured’s financial statements both prior to and after the loss. Such analysis may be performed internally by the business entity or by forensic accountants retained by the carrier (or both if there is a dispute regarding the claim amount). The following details the types of financial analysis generally performed.

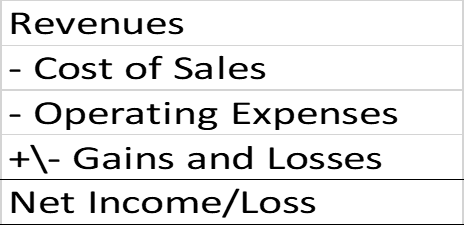

While an analysis of the entity’s balance may be performed, much of the relevant information for a business interruption claim resides in the income statement. The income statement (often referred to as the Profit and Loss statement, or “P&L”) is the statement of revenues, expenses, gains, and losses for the period ending with net income (or loss) for the period. The income statement formula of revenues less cost of sales less operating expenses +/- gains or losses equals net income/loss before income taxes. The cost of sales and operating expenses are comprised of both fixed and variable components. Or more simply:

Components of the income statement are defined as follows:

- Revenues—monies entering the business in the form of sales during the period.

- Cost of sales—monies leaving the business because of sales during the period. This includes prices for raw materials, labor, and overhead.

- Operating expenses—expenses incurred in carrying out the functions of the business, which typically include selling and general and administrative expenses. Management/sales payroll, rent, and utilities are examples.

The characteristics of the entity’s expenses differ based on the type of business. Service type businesses, such as a landscape concern, do not produce a product and will therefore likely have a higher labor cost percentage as part of the cost of sales than a manufacturing concern. Alternatively, a manufacturing entity, such as a smart phone producer, will have significant raw materials within cost of sales.

An analysis of fixed and variable expenses is also performed in business interruption claims. This information is generally not readily apparent within the income statement and is typically performed through interviews with management and the accounting staff or through statistical analysis. The reason this analysis is important is that variable expenses may not occur during the business interruption and would therefore be excluded from the claim.

What Expenses Are Allowed and Not Allowed in Business Interruption Claims

Generally, continuing (fixed) and incremental (mitigation) expenses are allowed and included in business interruption claims. Continuing (fixed) expenses are all expenses which are incurred despite the interruption. These expenses are fixed in nature, meaning that they are not able to change in the short term based on management’s decisions. Incremental (mitigation) expenses are necessary expenses incurred during the period of restoration that would not have been incurred had the event not occurred.

Non-continuing (variable) expenses are not normally included in a business interruption claim. Such expenses vary directly, sometimes proportionally, with business volume. These expenses would not ordinarily be incurred during the period of loss. There are certainly exceptions to this guideline. For instance, if an hourly employee (ordinarily considered a variable expense) was needed to keep portions of a factory operating, the relevant expenses may be considered fixed during the loss period. Examples of non-continuing (variable) expenses include the following:

- Sales commissions

- Cost of sales (or cost of goods sold)

- Bad debt expense

- Credit card transaction fees and sales discounts

- Payroll and related taxes (if employees were not paid during the loss period)

- Raw materials (if production did not continue during the loss period)

- Any expense, or portion thereof, that was not incurred because of the loss

The second part of this article will present a case example.

We would like to thank F. Dean Driskell III and Peter S. Davis for providing insight and expertise that greatly assisted this research.

[1] AICPA Practice Aid 10-1, Serving as an Expert Witness or Consultant.

[2] ACFE 2020 Global Study on Occupational Fraud and Abuse, Report to the Nations, page 8. Report may be downloaded for free at https://www.acfe.com/report-to-the-nations/2020/.

[3] Ibid, page 4.

[4] The Business Interruption Book, Torpey, Lentz, and Barrett, page 57.

Dean Driskell III, CPA, ABV, CFF, CFE, MBA, is an Executive Vice President in J.S. Held’s Forensic Accounting / Economics / Corporate Finance practice. He specializes in performing consulting services for clients involved in various types of accounting, economic, and commercial disputes as well as fraud and forensic accounting matters. With more than 30 years of experience in financial analysis, accounting, reporting, and financial management, he has served clients and their counsel in both private and public sectors, providing technical analyses, accounting/restatement assistance, valuation services, and litigation support across a variety of industries, and as an expert witness in litigation.

Mr. Driskell can be contacted at (404) 876-5220 or by e-mail to DDriskell@jsheld.com.

Peter S. Davis, CPA, ABV, CFF, CIRA, CTP, CFE, is a Senior Managing Director in J.S. Held’s Forensic Accounting / Economics / Corporate Finance practice. He has served as Receiver in regulatory matters brought by the SEC, FTC, Arizona Corporation Commission, the Arizona State Board of Education, as well as lenders and shareholders. His areas of expertise include: understanding and interpreting complex financial data, fraud detection and deterrence, and determination of damages. He has provided expert testimony in numerous federal, bankruptcy, and state court matters.

Mr. Davis can be contacted at (602) 295-6068 or by e-mail to PDavis@jsheld.com.