The Role of Forensic Accountants in Measuring and Detecting Fraud in Employee Loss Claims

With Examples From Asset Misappropriation to Financial Statement Fraud (Part II of II)

This two-part article (Read Part I here) focuses on the two significant, but different, roles forensic accountants play in quantifying employee losses and how—in the normal course of the analysis—they may find instances of fraud that require further investigation. The authors first provide detailed guidance for forensic accountants in how to quantify employee losses and later offer insights into behavior that may indicate fraud stemming from such claims. They also explain the factors considered by carriers when hiring external accountants. The second part of the article features two cases studies involving bribery and corruption and financial statement fraud.

Bribery and Corruption

Bribery occurs when a person offers something of value to another person in order to receive something in exchange. Corruption may be defined as dishonest or fraudulent conduct by those in power, typically involving bribery. Therefore, bribery is a subset of corruption. Bribery and corruption are common to both business and governmental concerns. Examples include:

- Employee accepting money or favors for free or reduced cost services

- Business bribing government or private officials to receive contracts

- Bid rigging—an illegal practice that involves competing parties colluding to choose a winner in an open bidding process

- Kickbacks—payments made to someone to facilitate a transaction or event

- Bribing management for a compensation or bonus increase

- Bribing public officials for changes to laws or regulations.

The first step in measuring a bribery and corruption employee loss event is the determination of what calculations must be done. Generally, the potential loss is assessed through analysis on the financial impact to the business. For example, if a bribe was paid by an employee, how was the bribe paid? Was it paid in cash, services, or through the transfer of inventory? The determination of the payment method will determine much of the needed analysis.

The documents required to complete this analysis will vary based on the type of business and complexity of the bribery or corruption. The following documents are typically requested in order to analyze such claims:

- Bank statements/bank reconciliations

- Copies of cancelled checks (original documents are preferable)

- Relevant contracts

- Inventory records and inventory write-off documentation

- Details of deposits and wire/ACH transfers

- General ledger (for relevant periods)

- Income/profit and loss statements

- Insured’s claim

- Police report (if applicable)

Again, it may also be appropriate to conduct interviews of relevant company personnel to gain additional information about the claim or the alleged losses.

The second step in measuring the employee loss is performing the appropriate analysis. The analysis may be as simple as looking at a bank account for a payment to an individual or a large cash withdrawal, or in more complicated situations, utilizing analyses to determine overcharges to cost centers or missing inventory.

Bribery Case Example

Case Study 3

MManufacturing, Inc., a business that produces microchips utilized in cellular phone applications, submitted an employee loss claim to XYZ Insurance Company. In its claim, the business alleged that a current employee paid bribes to a leading cellular phone manufacturer, Orange Cellular, in order to obtain a lucrative contract for microchips during 2021. In addition to the bribes, there were also allegations that the employee billed the client less than contractual amounts as inducement to obtain the contract. The estimated loss amount is unknown.

Below are examples of the documentation and information from the carrier and business that the forensic accountant may request in relation to a bribery loss:

- Cash and checks registers/logs

- ACH/wire transfer registers

- Bank statements/bank reconciliations

- Relevant contracts

- Accounts payable and payment ledgers

- Financial statements, including income, balance sheets, and cash flow statements

- Police report (if applicable)

The next steps are to evaluate and analyze the documentation and related claims. The forensic accountant may perform such analyses as follows:

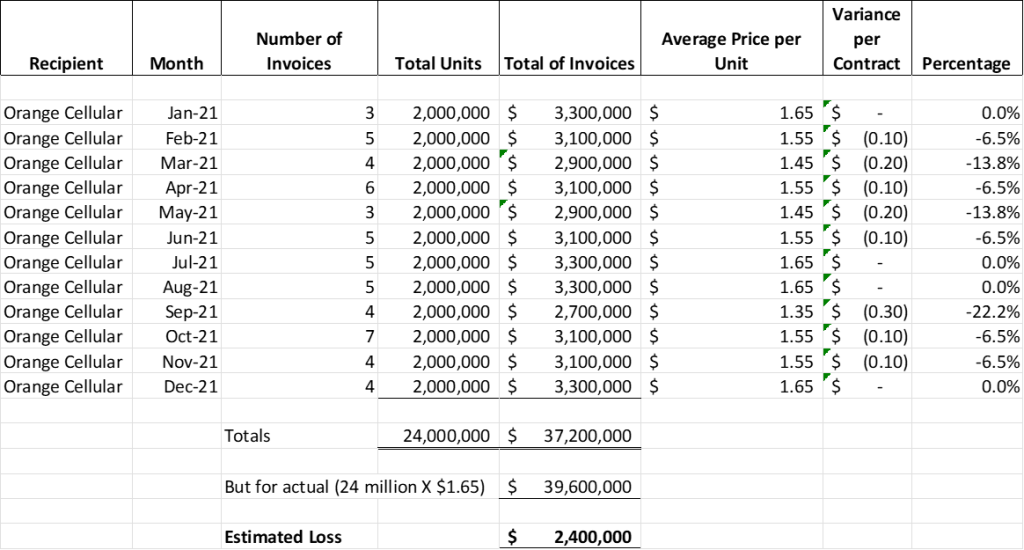

- First, an analysis of MManufacturing’s books and records indicate it entered a contract on January 1, 2021, to supply 2,000,000 microchips per month to Orange Cellular during 2021 at a total price (including freight) of $1.65 per chip. According to management, all chips were shipped, and all invoices were paid by Orange Cellular. Based on the review of the contract, the contract was signed on behalf of MManufacturing by Thomas Jome, Vice President of Sales, and on behalf of Orange Cellular by Melissa Rose, Senior Vice President of Procurement.

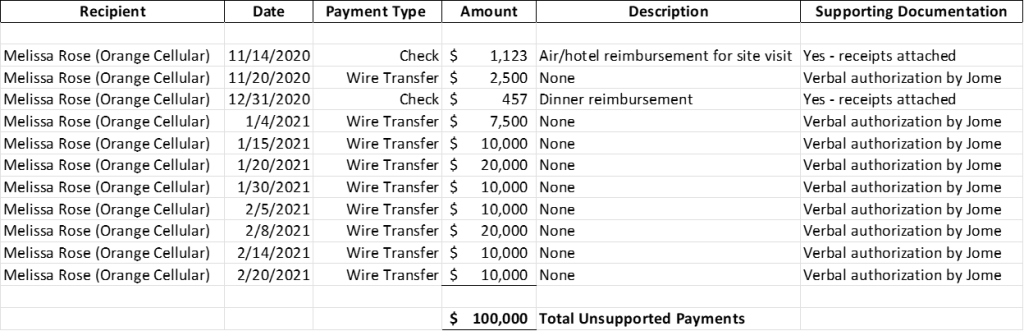

- Second, an analysis of MManufacturing’s check registers and ACH/wire transfers indicate multiple payments to Melissa Rose. Such payments should be evaluated for appropriate business purposes versus potential fraud.

- Third, an analysis of the invoices submitted by MManufacturing to Orange Cellular reveal multiple invoices with prices less than the contractual rate of $1.65 per chip.

- What is the amount of the potential loss?

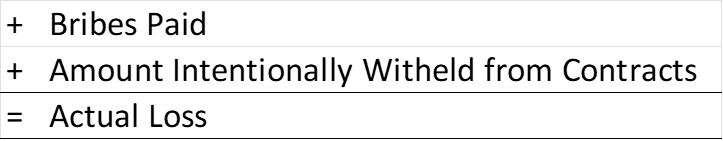

Therefore, the employee loss (i.e., value of the potential claim) may be calculated as follows:

The forensic accountant analyzed all payments to Melissa Rose as follows:

Based on the available data, 11 payments were made to Melissa Rose in 2020 and 2021—both via check and wire transfer. Two payments were made for the reimbursement of air travel, hotel, and dinner expenses for a site visit to MManufacturing’s corporate headquarters. Receipts and documentation were obtained from the files supporting these reimbursements. Nine wire transfers were made to Melissa Rose totaling $100,000. There was no supporting evidence for these payments.

According to the accounts payable manager, these payments were made based on verbal authorization from Thomas Jome. Each of these expenditures should be considered suspect and potentially fraudulent.

The forensic accountant then analyzed the relevant contract specifications along with the invoices and payments made to Orange Cellular. The following chart shows the total units sold per month (two million per month and 24 million in total), total invoices, and the average price per unit sold. The chart also clearly depicts that in certain months the average per unit charge is less than the contractual rate of $1.65 per unit.

The forensic accountant learned through interviews with the company’s invoicing and accounts receivable personnel that Thomas Jome authorized the deviations from the contractual rates.

The forensic accountant confirmed that Orange Cellular paid the $37.2 million in invoices. Therefore, the total loss may be calculated as follows:

The carrier and the terms of the insurance policy would determine whether the $2.4 million withheld from the contracts is payable under the policy. MManufacturing’s legal and (forensic) accounting fees may also be covered under the policy.

Financial Statement Fraud

In the simplest terms, financial statement fraud is the intentional misstatement of financial statements to deceive financial statement users. Such frauds may cause negative impacts to shareholder value through reductions in share price for publicly traded companies or through fines and penalties by regulators and governmental agencies like the SEC or the Department of Justice (DOJ). Examples include the following intentional acts:

- Overstating (or understating) revenues or expenses on the company’s income statements

- Inflating (or deflating) asset values on the company balance sheet

- Hiding obligations or other liabilities

- Disguising related party transactions or financing relationships

The first step in measuring a financial statement fraud loss event is the determination of what analysis must be done. Generally, the potential loss is assessed by analyzing the financial impact on the business. For example, if the chief financial officer intentionally overstated company revenues to increase the size of the executive bonus pool, the loss analysis may include the corrected revenues and the calculations of the corrected bonus pool. In a separate example, the intentional misstatement of financial statements may not be a specific loss event, but there may be costs associated with restating the financial statement by outside forensic accountants and law firms (which may or may not be covered under the insurance policy).

The documents required to complete this analysis will vary based on the complexity of the financial statement fraud. The following documents are typically requested in order to analyze such claims:

- Historical financial statements

- General ledgers

- Payroll and bonus documentation

- Bank statements and reconciliations

- Insured’s claim

- Police report (if applicable)

It also may be appropriate to conduct interviews of relevant company personnel to gain additional information about the claim or the alleged losses. Interviews are generally conducted in the following order:

- Friendly witnesses (whistleblowers/attorneys)—The first phase of interviews serves to establish facts and allegations. The attorneys may assist you with intelligence gathered to date. The whistleblower (if available) may provide greater details, facts, and circumstances related to the initial allegations.

- Neutral witnesses (supervisors/direct reports/tangential)—This second phase of interviews serves to confirm the facts obtained from the friendly witnesses and provide additional details. Such interviews are important to determine the reliability of the initial allegations.

- Adverse witnesses (potential accomplices)—This third phase of interviews focuses on other potential bad actors. Often, when confronted with accusations and supporting facts, adverse witnesses will confirm bad acts and provide details of the target’s involvement.

- Target witnesses—The final interview (if possible) is with the target(s) of the investigation. The interview is most efficient when performed last so that you can have all available information at your disposal to confront the target and rebut any false statements.

The second step is performing the appropriate financial statement fraud analysis, which is rarely simple and may become extraordinarily complicated. We examine a reasonably simple fraud in the section below.

Financial Statement Fraud Example

Case Study 4

Dee Homes, Inc., a business that develops residential subdivisions and builds single-family homes, submitted a claim to XYZ Insurance Company. In its claim, Dee Homes alleged that a group of three employees colluded to overstate 2020 and 2021 revenues to increase bonus payments for the executive team. The estimated loss amount is unknown.

Below are examples of the documentation and information from the carrier and business that the forensic accountant may request in relation to the financial statement fraud:

- Cash and checks registers/logs

- ACH/wire transfer registers

- Bank statements/bank reconciliations

- Relevant bonus agreements

- Accounts payable and payment ledgers

- Financial statements, including income, balance sheets, and cash flow statements

- Insured’s claim and policy

- Police report (if applicable)

The next steps are to evaluate and analyze the documentation and related claims. The forensic accountant may perform such analysis as follows:

- First, an initial interview with Dee Homes CEO, Jennifer Baez, revealed that an internal whistleblower reported through the company’s intranet site that one or more executives intentionally overstated company revenues in 2020 and 2021. The whistleblower further revealed that the fraud was accomplished through manual journal entries posted on the last day of each year and that the results of these entries significantly increased incentive bonus payments to a group of executives.

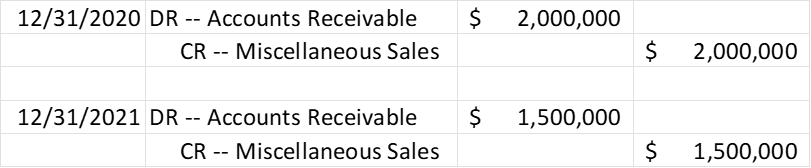

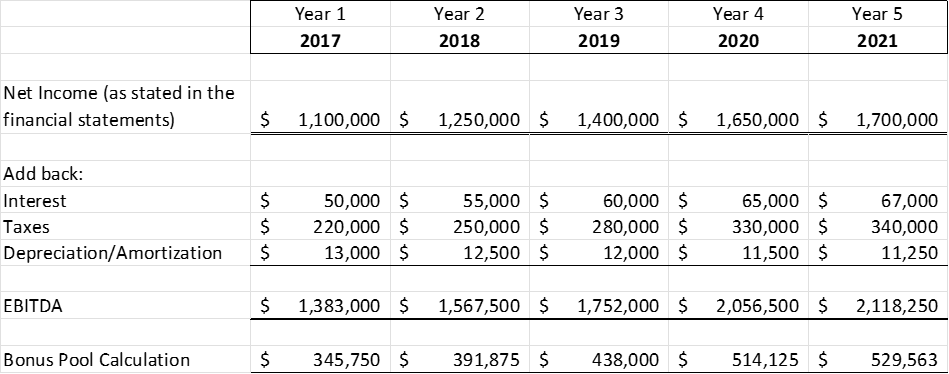

- Second, Baez reported that the company did have a special incentive bonus pool targeted to three corporate executives—the chief financial, operating, and procurement officers. Based on an analysis of the relevant bonus plans, the incentive bonus pool was calculated as 25% of EBITDA for each calendar year. Such bonuses were to be paid equally to the three executives on February 1 of the following calendar year.

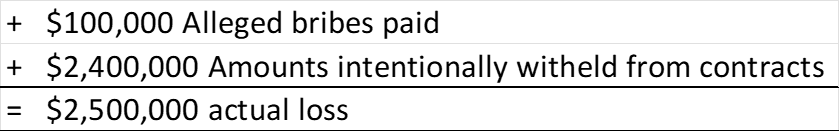

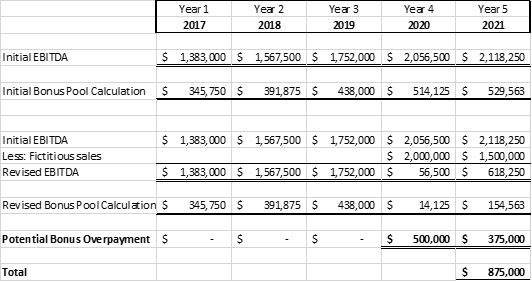

- Third, an analysis of the income statements and general ledgers over the past five years for Dee Homes revealed the following unsupported journal entries:

- Fourth, further analysis and interviews with accounting personnel revealed that the above entries were made at the request of the chief financial officer. The company’s books and records contain no support for these entries and no amounts have been collected on the accounts receivable balances to date. The forensic accountant determined these entries were unsupportable and overstated both net income and EBITDA.

- What is the amount of the potential loss?

Therefore, to find the employee loss (i.e., value of the potential claim), the forensic accountant should first calculate the executive bonus pool before adjustment for the above entries as follows:

In the next step, the forensic accountant adjusted EBITDA for the unsupported journal entries in 2020 and 2021 and recalculated the executive bonus pool. The following chart shows a potential overpayment and potential claim of $875,000.

Conclusion

Employee loss claims can be both complex to measure and have areas in which fraud exists. Insurance companies often bring in forensic accountants to quantify the employee loss. Those who have significant experience recognizing fraudulent schemes may also detect activity that merit further analysis and investigation. When hired to investigate these matters, forensic accountants must know how to identify the various signs and patterns that indicate that a fraud has occurred or is ongoing. In these cases, forensic accountants are called on to gain a unique understanding of how the claimant’s business operates—specifically how income, expenses, profit, and loss on a historical basis is realized. With this information and insight into the circumstances of the insured’s financial situation, a forensic accountant can identify instances of fraud within an employee loss claim.

We would like to thank F. Dean Driskell III and Peter S. Davis for providing insight and expertise that greatly assisted this research.

This article was previously published by JSHeld in JDSupra, June 07, 2022, and is reprinted here by permission.

Dean Driskell III, CPA, ABV, CFF, CFE, MBA, is an Executive Vice President in J.S. Held’s Forensic Accounting / Economics / Corporate Finance practice. He specializes in performing consulting services for clients involved in various types of accounting, economic, and commercial disputes as well as fraud and forensic accounting matters. With more than 30 years of experience in financial analysis, accounting, reporting, and financial management, he has served clients and their counsel in both private and public sectors, providing technical analyses, accounting/restatement assistance, valuation services, and litigation support across a variety of industries, and as an expert witness in litigation.

Mr. Driskell can be contacted at (404) 876-5220 or by e-mail to DDriskell@jsheld.com.

Peter S. Davis, CPA, ABV, CFF, CIRA, CTP, CFE, is a Senior Managing Director in J.S. Held’s Forensic Accounting / Economics / Corporate Finance practice. He has served as Receiver in regulatory matters brought by the SEC, FTC, Arizona Corporation Commission, the Arizona State Board of Education, as well as lenders and shareholders. His areas of expertise include: understanding and interpreting complex financial data, fraud detection and deterrence, and determination of damages. He has provided expert testimony in numerous federal, bankruptcy, and state court matters.

Mr. Davis can be contacted at (602) 295-6068 or by e-mail to PDavis@jsheld.com.