Understanding IPCPL Theory, Evidence, and Application

Use in Private-Business Valuation (Part I of II)

This two-part article in this continuing series explains the implied private company pricing line (IPCPL). IPCPL explains and predicts how buyers and sellers of capital assets in private markets set risk-adjusted discount rates under conditions of non-zero transaction cost differentials between public and private markets; and, accordingly, IPCPL explains and predicts the shadow price of liquidity risk—the price of liquidity risk were it traded directly in private capital markets.

What is IPCPL Theory?

Despite widespread misunderstandings of implied private company pricing line (IPCPL), it can and will be shown in this article that the answer to the question—what is IPCPL theory and why is it important—can be stated quite directly:

IPCPL explains and predicts how buyers and sellers of capital assets in private markets set risk-adjusted discount rates under conditions of non-zero transaction cost differentials between public and private markets; and, accordingly, IPCPL explains and predicts the shadow price of liquidity risk—the price of liquidity risk were it traded directly in private capital markets.

IPCPL is eminently relevant to privately-held business valuation

The generally accepted valuation methodologies of using the build-up method (BUM) or capital asset pricing model (CAPM) are not actually based on financial theory relevant to transactions of small and medium sized closely-held enterprises (SMEs). This is why the IPCPL theory is important.

The IPCPL is a theory developed over the last decade; primarily from the insights of Bob Dohmeyer, Pete Butler, and Rod Burkert beginning in 2012. The IPCPL theory explains and predicts why risk-adjusted discount rates differ between publicly-traded capital assets and privately-held capital assets; specifically, for SMEs. Valuation professionals have expressed skepticism that such a relationship exists. Others believe there is no necessary relationship between public and private capital markets (e.g., those believing public and private markets operate completely independently).

James Hitchner’s (“Hitchner”) comprehensive text on business valuation, Financial Valuation: Applications and Methods, suggests the fundamental assumption underlying SME valuation is what is referred to as the economic principle of substitution, the law of one price, or the no-arbitrage principle. IPCPL theory is the first SME valuation theory that explicitly uses this principle to explain and predict the relationship between public and private capital markets; at least those that could reasonably be characterized as fair markets. In short, if data available on private market transactions (e.g., DealStats and Bizcomps data) does not represent fair market transactions, then the economic substitution principle essentially requires the existence of a theory connecting public and private capital markets. IPCPL is precisely such a theory, and it is a coherent theory of the relationship between public and private capital market risk-adjusted discount rates set under fair market conditions. Further, IPCPL can be supported with substantial empirical data.

To understand IPCPL theory, however, it is first necessary to understand more generally the existing business valuation theory. IPCPL theory does not replace existing valuation theory; it, rather, augments existing modern asset pricing theory as applied to capital assets sold in private market transactions.

What is the theory of business valuation?

A theory can be defined as a combination of sentences and equations that explains and predicts some phenomenon. It is based on a hypothesis that can be tested. What does business valuation theory explain and predict?

Fair market value is defined as “The price … at which property would change hands between a hypothetical willing and able buyer and a hypothetical willing and able seller, acting at arm’s length in an open and unrestricted market, where neither is under compulsion to buy or sell and when both have reasonable knowledge of the relevant facts” (Hitchner, 2017, Financial Valuation: Applications and Methods, pp. 4–5; emphasis added).

So, confining discussion to valuation theory in the context of the definition of fair market value (FMV), the theory should explain and predict the expected (hypothetical) price of a capital asset under a certain set of conditions with respect to (i) the structure of the market and (ii) the economic characteristics and information sets of buyers and sellers.

A critically important distinction to make at the outset is that any theory of valuation is not a theory explaining and predicting what valuation professionals think and do, i.e., the theory is about what buyers and sellers of businesses do with real money, not about what professionals theorize about what such buyers and sellers do or should do.

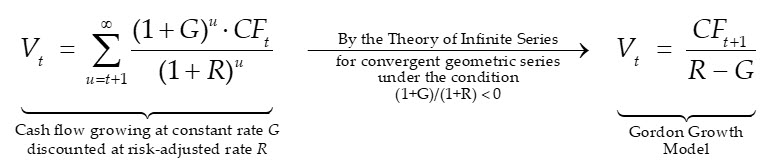

It is also important to distinguish between a theory and a tautology. A theory explains and predicts something, whereas a tautology is simply true by definition. Consider, for example, the Gordon Growth Model (see Hitchner, 2017, pp. 135), which says that under certain conditions, the value of a firm’s equity (V) is equal to next period cash flows (CF), divided by the cost of capital, minus the perpetual, long-run growth rate of the cash flow (R – G):

This is not a valuation theory; it is a tautology defining value under two assumptions: (i) a cash flow stream growing at a constant rate to infinity and (ii) the cash flow stream discounted at a constant risk-adjusted rate to infinity. It is not a valuation theory because it does not explain and predict how a buyer or seller of a business would estimate future cash flows, growth rates, or discount rates.

So, a theory of business valuation—or, more generally, a theory of capital asset valuation—must generally explain and predict how buyers and sellers estimate either expected future cash flows or risk-adjusted discount rates; or both.

What is the existing theory of business valuation?

This is an interesting question. A review of Hitchner (2017) suggests it can be answered in two, seemingly simple statements:

Business valuation theory:

Value today always equals future cash flow discounted at the opportunity cost of capital.

[The market approach] is based on the economic principle of substitution.

(Hitcher, 2017, p. 118 and p. 290, respectively)

Both such statements must hold at the same time and they both must be true because FMV must be the same under any valid valuation method. The idea that valuation estimates differ across valuation methods is irrelevant; that estimates differ is not a result of facts about the real world but, rather, is simply an artifact of either deficiencies in, or application of, the valuation methods being used.

Note that the AICPA Statement on Standards of Valuation Services (SVS Section 100.02) indicates that we are engaged to estimate value and our resulting estimate of value results in a conclusion of value. However, whether we call our result a conclusion or opinion of value, it is still an estimate of value.

Reading further in Hitchner (2017) with respect to the business valuation theory summarized in the two sentences above and confining discussion mainly to the opportunity cost of capital (OCC) of equity, several observations follow:

— There appears to be no explanation or prediction of how business buyers and sellers develop expectations of expected future cash flows; only a statement that projections underlying valuation estimates should be supported by disclosure of relevant assumptions.

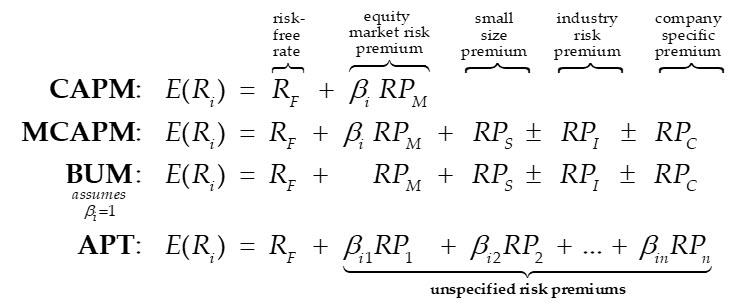

— OCC according to Shannon Pratt and Roger Grabowski (2014, Cost of Capital—Applications and Examples, 5th Edition, p. 77) (“Pratt” and “Grabowski” hereafter) apparently carries an a priori definition based on a risk-free return plus premiums related to maturity risk, capital market risk, company-specific risk, and liquidity and marketability risk. Hitchner (2017, pp. 193–196) characterizes OCC in terms of four models with which the experienced valuation professional is no doubt familiar:

Each of the above models is an attempt to derive the OCC. In theory, the resulting OCC should be the same under each model. However, this is rarely, if ever, the case. This is because the CAPM, MCAPM, and BUM do not represent empirical reality. It follows then, that the underlying theories are invalid. This is generally the case with CAPM: Fama and French (2006, p. 43) state that “The [original] version of the CAPM … has never been an empirical success. … The problems are serious enough to invalidate most applications of CAPM.”

Pratt and Grabowski (2014) appear to suggest MCAPM and BUM represent valid valuation theories that repair the defects in CAPM but, unfortunately, this cannot be the case: (i) both models include a company specific risk (CSR) premium that—if truly company-specific—must represent unsystematic risk, which is optimally diversified rather than priced under existing asset pricing theories like CAPM and APT; and, (ii) to the extent CSR is a systematic risk, existing theory—at least as presented in Hitchner (2017, pp. 193–196)—is silent with respect to an explanation and prediction for how such risk is priced by buyers and sellers of businesses.

With respect to the general form of the arbitrage pricing theory (APT) model presented above, Hitchner (2017, p. 196) simply notes capital market, confidence, time horizon, inflation, and business cycle risks would normally be considered estimating OCC under APT; adding, however, that “APT is not widely used in … valuation … due to the unavailability of usable data … .” Although it is true that APT is not widely used in private capital asset valuation, there is usable data required for estimating the FMV of privately-held SME equity. (This will be shown in a future article.)

David Goodman, MBA, CPA, CVA, has 25 years of experience in performing business valuations and forensic accounting services for family law and business disputes. He also has prepared business valuations for tax and buy-sell purposes. He has an MBA from the Amos Tuck School at Dartmouth College. He is a past-president of the NACVA-Mass State Chapter, past chair of the Massachusetts Society of Certified Public Accountants Litigation and BV committee, and a past board member and treasurer of the Massachusetts Collaborative Law Council. As a financial neutral, Mr. Goodman has helped divorcing couples reach peaceful equitable solutions. He has presented on business valuation and tax issues related to divorce at NACVA annual conference, NACVA-Mass. State Chapter, and the Massachusetts Collaborative Law Council. He has also testified as an expert witness in court and arbitration. He is currently serving on the editorial board of QuickRead.

Mr. Goodman can be contacted at (617) 698-3950 or by e-mail to dgoodman@joacpa.com.

Malcolm McLelland, PhD, has 40 years of professional and academic experience in finance and accounting, including positions in commercial banking, consulting, and educational institutions. His primary expertise is the use of econometric and financial modeling methods to assist clients with issues related to capital markets, financial reporting, and financial management. He has 15 years of international experience spanning client engagements in the United States, Brazil, and Southeast Asia. He has published in both academic and professional journals on finance and accounting topics, and has taught courses and presented seminars on finance- and accounting-related topics in major U.S. universities, Germany, and Latin America.

Dr. McLelland can be contacted by e-mail to mmc@mclelland-financial-economics.com.