IRS Cannabis Compliance Report, Wrong!! Why?

A Forensic Investigation Opens IRS-Floodgate!

In this article, the author critiques the IRS Participant Guide for Marijuana Companies. This 200-page guide provides general instructions to the service on the valuation of cannabis farms. The author argues that the compliance guide is completely inaccurate concerning the audit of cannabis cultivation. The author proposes that forensic and valuation professionals employ a series of tests in lieu of the IRS guidance.

William Fowler, a former IRS Large Case Exam Officer, agrees with renowned attorney, Nick Richards of Greenspoon Marder, that the general suggestions of the IRS pertaining to its Cannabis Compliance Initiative is misleading or “ridiculous” in several respects. The general instructions of the IRS’s 200-page cannabis compliance guide are completely inaccurate concerning the audit of cannabis cultivation. Per this internal training document for IRS agents, it states: “If you perform a light count during a tour, you can perform a rough estimate of the expected yield from that harvest. Generally, a 1KW light and ballast module will produce 1.5 to 2.0 pounds of dried saleable product within a cycle, and there are usually five to six harvest cycles per year.” Source: IRS Participant Guide for Marijuana Companies, pg. 19, 04-2015.

First, let’s examine the yield of 1.5 to 2.0 pounds of dried saleable product per 1KW of light. In order to achieve five to six harvest cycles per year, the grower must be cultivating auto-flower plants, known as Ruderalis, which can produce product possibly every two months … but these plants only reach a height of approximately 7 to 20 inches; therefore cannot, because of their exceedingly small size, produce 1.5 to 2.0 pounds of dried saleable product per 1KW light as the IRS would suggest.

One must inquire as to what is the spacing for these auto-flowering plants? Most commercial growers do not use auto-flowering plants because they yield much less and have less THC than indica or sativa strains of cannabis. After-all, most commercial growers try to achieve high THC in their production, which consumers target when purchasing cannabis. It should be noted, there are several missing audit questions that the IRS examiners should be asking, such as: How long are the lights on for the auto-flowering plants, if indeed this is the cannabis strain being utilized? What is the periphery equipment used in the grow area? How many air conditioning units? What is their KW usage? How many fans used and their KW usage? How many other rooms, not in the grow area, are using electricity and what is that KW usage? What other periphery equipment usage and its KW usage? All the periphery equipment should be excluded from the electric bill to establish just KW usage devoted to the lights. What is the specific strain of cannabis in the grow area and the normal yield per plant? What is the spacing of each cannabis plant? How long has the grower of this company been growing cannabis? There is a need to know his experience, since experienced growers tend to produce more yield than inexperienced growers.

These questions and more are pertinent to the forensic audit since all these factors are needed for the correct yield per light. When calculating yield to electric usage it is not simply the wattage that determines yield, but several factors previously mentioned. Like any farm crop, whether it is wheat or cannabis, many factors are involved with the production of the crop, especially the expertise of the farmer and the tools at his disposal.

The erroneous assumptions the IRS is utilizing, especially as it pertains to light KW yield, would put most cannabis operations, if not all, under an audit unnecessarily. These audit assumptions should be corrected by the IRS because unnecessary expenses are incurred by both the government and private sector.

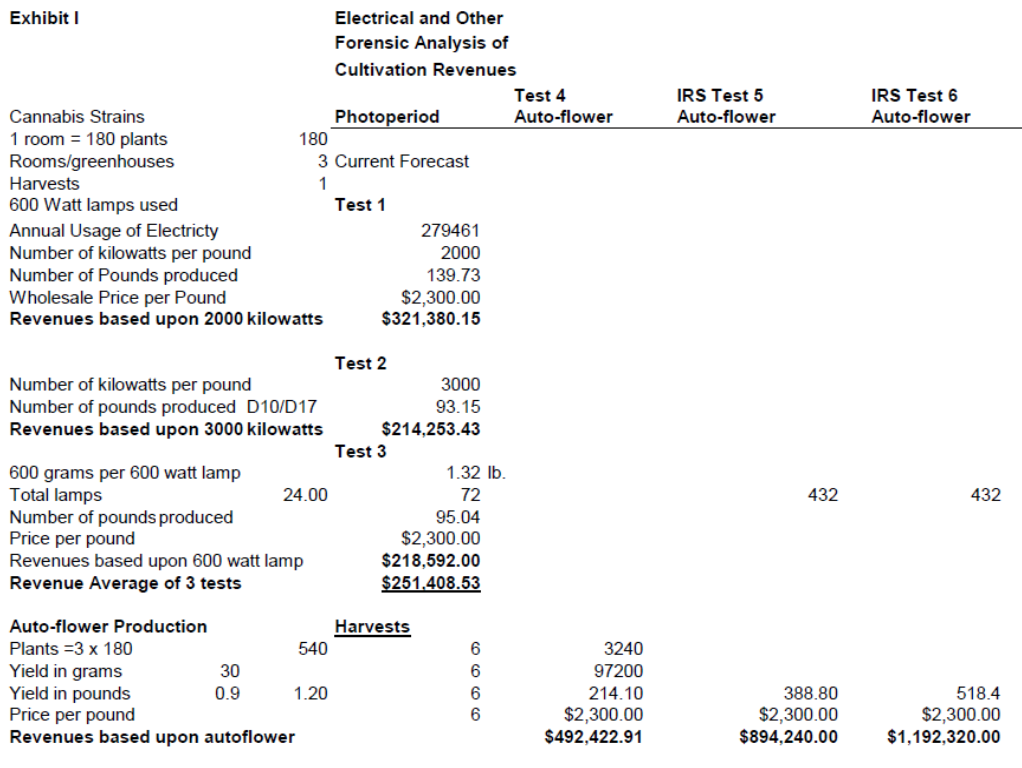

I would suggest, as a Master Analyst in Financial Forensics (MAFF) to use several alternate tools to derive a more accurate yield of cannabis. For example, it is more accurate to use the average of different methods of electrical use to determine average yield and revenues. If we were to peruse Exhibit 1, we can see how photo period cultivation differs notably from auto-flower cultivation. For example:

Tests 1 and 2, actual tests illustrated in Exhibit 1, reflect an actual grow operation in Carson City, Nevada. Clients retained me to derive a valuation for investor interest. Subsequently, I took the annual kilowatt usage for their three rooms of cannabis operation with 180 photoperiod plants per room. The experienced grower was utilizing 24, 600-watt lamps per room, or 72 lamps total. Since the plants were photoperiod and usually require a full one-year season, only one harvest, not five or six as the IRS compliance report would suggest. Additionally, I took the total kilowatt usage for one year and subtracted 5 percent for the use of air conditioning and other peripheral equipment to establish the total kilowatt usage for one year of harvest. The year’s usage of electricity was 279,461 kilowatts. Electricity bills are established in kilowatt, not watts of usage, and there are 1,000 watts to each kilowatt.

Tests 1 and 2 represents the actual verbiage from a Google search as quoted as follows: “According to the Northwest Power and Conservation Council (NPCC), indoor commercial cannabis productions can consume 2,000 to 3,000 kilowatts hours (kwh) of energy per pound of product.” Please notice on Exhibit 1, the calculation of the 2,000 and 3,000 kilowatts per pound or 139.73 and 93.15-pounds production priced at $2,300.00 per pound, with a resulting revenue of $321,380.15 and $214,253.43 in total revenues for Tests 1 and 2. Price per pound is based on prior years, not current.

Test 3. Within the growing community, the upper limit of one gram per watt is typically used. This means that for every watt of light you can hope to obtain one gram of product back. So the average yield per plant under a 600-watt lamp would produce 600 grams. For three rooms and 24 lamps per room, we have a total of 72 lamps. If we convert 600 grams to pounds it is equivalent to 1.32 lbs., which derives a total of 95.04 pounds; and priced at $2,300.00 per pound, results in $218,592.00 revenues. The average of these three tests results in total revenues for one year of production for photoperiod plants is $251,408.53.

Test 4 utilized the auto-flower commercial production, which is published on Google as stating, “Average auto-flower plants yield an average 20 to 60 grams per plant. This is calculated based on final dried bud content.” Continuing with Test 4, we have 540 plants (three rooms times 180) and now utilizing six harvests per year, which would provide 3,240 plants (540 times six). I used an average yield of 30 grams per auto-flower plant with a resulting 162,000 grams, converted to pounds (162,000 grams divided by 454 grams equals 356.8 pounds). Again, using $2,300 per pound provides $492,422.91 in revenues based upon six harvests. Price per pound is not the current price.

Tests 5 and 6 utilized the IRS’s auto-flower assumptions, which represents in Test 5 the assumption of nine tenths of a pound equates to a 600-watt lamp. In this analysis, I first needed to equate a 1.5 pound to one kilowatt as the IRS states. Since we are using 600-watt lamps, I used an algebraic expression to convert a 1000-watt lamp that produces 1.5 pounds to a 600-watt lamp, which is used in our analysis. One kilowatt represents 1000 watts, so 600 watts is equal to nine tenths of a pound. In IRS Test 5, we have 72 lamps times six harvests equal 432 lamps at nine tenths of a pound equals 388.8 pounds, so total pounds priced at $2,300 equals $894,240.

Test 6 utilized the IRS assumption of two pounds per 1000-watt lamp. Again, I needed to convert the 1000-watt lamp to a 600-watt lamp in our analysis. I used the algebraic expression of converting a 1000-watt lamp and derived 1.2 pounds for each 600-watt lamp used in this analysis. Additionally, we take 432 lamps at 1.2 pounds for each lamp, which equals 518.4 pounds times $2300.00 equals $1,192,000 in revenues, according to the IRS assumptions.

IRS Tests 5 and 6 utilized the assumptions presented in the IRS’s compliance report and the following narrative represents the huge discrepancies between photoperiod plants and auto-flower plants, and how revenues can be distorted if this distinction is not recognized at the beginning of the forensic audit stage. Additionally, if we look to the commercial average of auto-flower plants and compare to the IRS Test average ($894,240 and $1,192,320/2) of $1,043,280 compared to the commercial average of $492,422.91, we can see an enormous difference in revenues of basically twice as much!

Note, the IRS would be expecting their assumption of revenues from the commercial auto-flower operation of five to six harvests, which could not meet IRS revenue projections. If the IRS contends that their assumptions are correct and assess taxes based on their figures, wouldn’t this possibly put the cannabis operator at a huge disadvantage? Wouldn’t it be advantageous if you have the tools to fight the IRS on just this issue? Within the IRS Compliance Initiative Project Authorization, page 4 has a table that reflects that the IRS receives, on average, $1,375 dollars per hour for a cannabis audit versus only $475 dollars per hour for a regular non-cannabis business audit. However, in 2015 within California, the IRS found the average cannabis industry audit resulted in $2,788 per hour in taxes versus $686 per hour for the non-cannabis business (MJBiz Daily, 4/12/2021 updated 2023). Additionally, it takes 24.5 hours of audit time for the cannabis audit versus 34.9 hours for a non-cannabis business audit. Isn’t this a bonus incentive for the IRS to focus on cannabis audits? Let’s just speculate on why the IRS is going to hire 87,000 new agents? Do you suppose they are going to audit where the most tax revenues are coming from, cannabis?

On a personal note, I did perform this forensic analysis based upon a photoperiod cannabis operation in Carson City, Nevada, based upon one year of operation as represented in my analysis, Tests 1 through 3, but the client’s actual booked revenues were much less than what was calculated based solely on electrical usage.

I advised my clients about my forensic analysis, which was used in preparation of my valuation report. They could not believe that their actual revenues were “less” than what I had calculated for them. I told them that there could be theft in their operation, but they were taken back by the concept that their grower or any employee within the operation could be stealing from them. As it turned out, a year later at a cannabis conference, my clients came up to me and said, “Bill, we installed cameras at our grow location, and guess what, our grower was stealing product out the front door. We installed security cameras, because of your analysis, and had the thief on camera.” Unfortunately, they had lost so much product, they were forced to put their operation up for sale. True story!!

Another critical issue this client was not aware of is the use of the wrong National American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code regarding identifying the grow operation. My client’s certified public accountant had identified their grow operation under a manufacturing facility. This oversight, on the CPA’s part, whether intentional or not, could subject my client to more scrutiny by the IRS and they might suggest this was intentionally done. Consequently, the company’s tax return would be subject to a cannabis audit. Mistakes like this could lead the IRS to recommend fraud, and therefore, no statute of limitations apply as to requesting previously filed tax returns.

According to the IRS’s Participant Guide, page 10, there is a discussion of what cannabis operators can say or not say based upon the entity structure. Per the IRS’s quote, “Most of the taxpayers in this industry operate through LLCs, partnerships, or incorporated entities. Collective entities such as these are not entitled to a Fifth Amendment privilege” (see Braswell v U.S. 487 U.S. 99, 104 [1988]). This is an important statement as to the initial structuring of a cannabis operation. Obviously, from this financial analysis, a valuation or a forensic analyst should take into consideration whether the grow operation is run by a novice or an expert grower and specifically what kind of plants are grown, either photoperiod or auto-flower, along with other considerations listed in this presentation. Additionally, make sure the NAICS code is applicable to the grow operation; if it is wrong then this raises a red flag to the IRS.

Another statement made in the IRS’s Participant Guide, regarding substantiation of expenses, reads as such: “In a well-developed case the examiner always considers expenditures which are reasonable, ordinary and necessary trade or business expenditures. In non-filer, or other lack of, records cases often the examiner considers the use of bizstats in an effort to allow reasonable business expenditures. Unfortunately, there are not Bizstats for marijuana businesses at this time.”

It is interesting to note that at the time this statement was made, over 173 cannabis audits had been made at the end of 2013, and yet the IRS had not made a study of similar business statistics that they could use internally. Since, they are using flawed audit procedures that would select most cannabis businesses, why not develop a study like Bizstats’ to use for the cannabis industry? Since there are no cannabis company statistics at hand, consequently, most cannabis valuations must use the discounted flow model.

As noted, there are many questions yet to be addressed by the IRS regarding these flawed assumptions and hopefully corrected so that both sides have an even playing field. Let’s help close the floodgates of IRS cannabis audits and save many American growers the anxiety of such tax audits.

Mr. Fowler has more than 40 years’ experience in both the private and government sectors, covering such disciplines as financial accounting, tax, valuation of corporations, and mergers and acquisitions with such companies as Sempra Energy, but trained by McKinsey and McKinsey and later recruited by Los Angeles Large Case Exam, IRS. Mr. Fowler has authored articles for NACVA in the past and was recognized for his work on the estate tax case of Kaufman vs. Commissioner as an expert valuation witness in the Federal Tax Court.

Mr. Fowler can be contacted at (530) 913-7228 or by e-mail to wkfowlerconsulting.com.