Boundaries in Business Appraisal

Appraisers Should Focus on Objectivity and Competence and Be Ready and Flexible to Deal with Unanticipated ChallengesâFrom Vague Case Law to New Evidence to Erupting Personalities.

Rand Curtiss expounds on his philosophy that business appraisal is about boundaries: limits on what we can do. Every work challenge is filled with a large number of people, each of whom have different boundaries. Business sellers want emotionally high prices. Plaintiffs want to destroy defendants. Taxpayers want to minimize taxes. Scenarios are complicated by the fact that a central problem in business appraisal is balancing the purely scientific with a bit of the artistic. Here are some tips.

Business appraisal is about boundaries: limits on what we can do. Whatever your level of competence, you encounter boundary issues in every engagement. This article provides perspective on dealing with them.

An Example

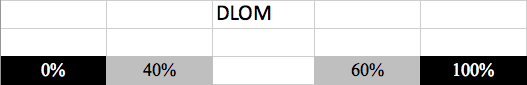

We are appraising a discount for lack of marketability (DLOM). We know for sure that it cannot be under 0% or over 100%. A 0% discount implies a marketable (as if freely traded) level of value, like that for 100 shares of General Motors stock. A 100% discount implies a zero interest value, which might occur for equity in a business with a potentially infinite environmental liability. (Nobody would buy it). With no analysis, a little logic and common sense, we have bounded the DLOM from 0% to 100%, a significant improvement from -â to +â! So far, so good.

The next, harder step is to use case facts, market data, and accepted appraisal techniques to the best of our ability to narrow our estimate of the DLOM with reasonable confidence/certainty. This is the scientific part of business appraisal: it involves data, logic, technique and skill. Assume that we correctly used them to estimate a DLOM range of from 40% to 60% (These numbers are rounded, purely hypothetical, and arbitrary, and are absolutely not a guideline or suggestion for any real DLOMS. This point cannot be emphasized strongly enough. This writer has often appraised DLOMs that are far less than 40% and sometimes appraised them at greater than 60%.).

Only because we have to opine an amount certain for the value of the subject interest (for tax, legal and/or transaction purposes, the three major applications of business appraisals) must we be more specific about the DLOM, reducing it to a single number (point estimate)  when, in fact, it is a highly uncertain continuous variable that could be anywhere from 0% to  100% with varying probabilities. This is the artistic part of business appraisal: it involves judgment and experience.Â

The following diagram presents this graphically:

This diagram, to which repeated reference will be made, shows that the DLOM is surely not below 0% or above 100%, so those ranges (and beyond) are shaded black. It shows that analysis limited the DLOM range to from 40% to 60% with reasonable certainty, so the ranges from 0% to 40% and 60% to 100% are shaded gray. The zone in the middle, from 40% to 60%, where the DLOM point estimate falls, is shaded white. The white zone is the âsweet spotâ: the range of feasible values based on scientific analysis.Â

The central problems in business appraisal are:

- Scientific: to confidently minimize the sweet spot.

- Artistic: to competently select a point estimate within the sweet spot.

The diagram is overly simplistic because it suggests that the DLOM is a discrete variable (it has a specific value or range of values). A more accurate representation of the diagram would be drawn in two dimensions as a probability distribution, although it is usually impossible to ascertain its shape (symmetric bell curve, skewed, straight line implying equal probabilities, etc.). Â That is the province of statistical analysis and is beyond the scope of this discussion (See the article entitled âStatistical Confidenceâ in the Spring 2003 issue of Business Appraisal Practice, which explores that topic.) Statistical confidence intervals are rigorous mathematical expressions of boundaries that are continuous, not discrete (Our 40% to 60% DLOM estimate is reasonably, but not 100% certain. The DLOM could be, say, 20% or 80%, although that is highly improbable.).Â

Boundaries Are Pervasive

The DLOM example involves one technical aspect of business appraisal. Boundary issues pervade what we do at all levels. They arise when we are dealing with clients and their advisors:

- Business sellers usually want emotionally high prices that have no relationship to or justification in marketplace reality

- Plaintiffs want to destroy defendants

- Taxpayers want to pay no taxes

One of our first boundary-management challenges is to explain that (if we are acting as appraisers, not as consultants) we must be objective: we abide by compulsory professional standards and laws. Competence is also a boundary issue (See IBA Business Appraisal Standard 1.1: the first one of all!)Â

A major class of boundary issues involves the law, which does not always comport with marketplace reality and appraisal theory:

- At the statutory level, there is controversy about consolidating industries: should fair market value (âany willing buyerâ) include strategic buyers?

- At the case law level, should S corporation earnings be tax-effected?

- At the administrative level, what happens when you appraise a 30% DLOM and the service offers a 10% discount with no empirical support?

- At the jurisdictional level, what if the use of multi-period (discounted) benefits methods is prohibited (but otherwise appropriate)?

Boundary issues abound in the technical aspects of business appraisal. In fair market value appraisals, we must consider the willing seller as well as the willing buyer. We must assess the impacts of the economic outlook, the industry outlook, qualitative aspects of the business (such as depth of management and key person risk) as well as its capacity for growth, benefit generation and risk. Boundary issues arise when we develop discount and capitalization rates, premiums and discounts for fractional interests, and when we reconcile value indications developed using different premises, approaches and methods.

At each level, boundary issues influence our estimate of the sweet spot, moving it right or left or making it wider or narrower.Â

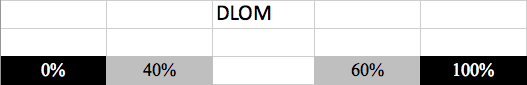

Take another look at the boundaries diagram:

Let darkness connote hardness. The black is stone. The white is air. The gray is malleable due to boundary issues (An idealized diagram would have increasing and decreasing grayscales symbolizing probability rather than five separate blocks which imply discreteness.).

Case facts and market data are bricks. The more and the better they are, the darker, wider, and stronger the boundary walls will be. Good appraisal practice, sound methodology, and good writing are the mortar holding the bricks together. Bad practice, methodology, and writing are spilled mortar: they look bad, are sticky, and obscure the sweet spot.Â

We are permitted to use certain kinds of bricks and mortar: market data, case facts, and techniques generally accepted in the financial community. We cannot use case verdicts or settlements as market data. Those are rivets: we are bricklayers, not steel workers, and union work rules prohibit crossÂutilization.

Implications

So what does all of this mean and how can we use it?

- Try to develop an instinct for the sweet spot and what values are inside and outside of it (For the more mathematical, visualize the shape and parameters of the probability distribution).

- When you have determined the sweet spot to the best of your ability, be honest about its dimensions. The best we can do scientifically is to narrow it to a reasonably certain range. Inside it, honest men and women of equal competence can have legitimately different opinions. Accept and respect that. True professionals who arrive at different value conclusions can always reconcile the differences in their opinions in terms of specific assumptions, even if they still disagree about them.Â

- Understand the concepts of confidence intervals and margins of error covered in basic statistics texts, even if you never use them.Â

- Remember the difference between precision and specificity. Precision implies accuracy. Specificity is how narrowly you define a number or a range. Do not quote discount or capitalization rate percentages with decimal points (e.g., 26.7%). Your estimate of the specific-company equity risk premium is far more uncertain than 0.X%.

- Trust your gut: if you are uncomfortable, a boundary is being violated. Try to figure out what it is. If you cannot, call for help.Â

- Do not opine on areas outside your professional boundaries. You are not a lawyer, fixed asset appraiser (or maybe a CPA). Issues that fall partly or fully in those bailiwicks must be addressed by those professionals. Have a network of individuals with complementary skills as well as mentors who can advise you.

- Stay within our professional society boundaries: follow standards! Know your role and responsibility as an appraiser, consultant, appointed arbitrator, mediator, third appraiser, etc.Â

- Avoid speculation (guessing outside) your boundaries. As an example, when using transactions from the IBA Database, we have no knowledge of the buyers and sellers. Do not tease the data to conclude that transactions reflected strategic or financial buyers. We do not have the facts to do this.Â

- Continuing professional education increases your personal boundaries and helps you narrow appraisal boundaries!

This article first appeared in the Winter 2003-2004 issue of Business Appraisal Practice.

Rand M. Curtiss is IBAâs Mid-Atlantic Regional Governor, President of Loveman-Curtiss, Inc. in Pepper Pike, Ohio, and Chair of The American Business Appraisers National Network. He can be reached via e-mail at rand@curtiss.com or by phone at (216) 831-7038.