Using PPA Data as Comparables in Upcoming Valuations

The Case of Trademarks and Brands

Since the adoption of fair value accounting governed by SFAS 141 (in 2001) and IFRS 3 (in 2004), hundreds of thousands of different intangible assets have been valued, audited, and reported in financial statements of public companies all over the world. After fifteen years of fair value accounting, the debate about the accuracy of such values and their relevance for readers is no less controversial than at its beginning. This is a pity because, in its essence, fair value data is an excellent resource for corporate finance professionals to understand more about the value drivers of businesses, and for valuation professionals to use reported values as comparable data. In the following article, the author argues in favor of an unprejudiced usage of fair value data on intangibles, in particular for trademarks and brands.

Since the adoption of fair value accounting governed by SFAS 141 (in 2001) and IFRS 3 (in 2004), hundreds of thousands of different intangibles assets have been valued, audited, and reported in financial statements of public companies all over the world.  After fifteen years of fair value accounting, the debate about the accuracy of such values and their relevance for readers is no less controversial than at its beginning.  This is a pity because, in its essence, fair value data is an excellent resource for corporate finance professionals to understand more about the value drivers of businesses, and for valuation professionals to use reported values as comparable data.  In the following article, the author argues in favor of an unprejudiced usage of fair value data on intangibles, in particular for trademarks and brands.

Since the adoption of fair value accounting governed by SFAS 141 (in 2001) and IFRS 3 (in 2004), hundreds of thousands of different intangibles assets have been valued, audited, and reported in financial statements of public companies all over the world.  After fifteen years of fair value accounting, the debate about the accuracy of such values and their relevance for readers is no less controversial than at its beginning.  This is a pity because, in its essence, fair value data is an excellent resource for corporate finance professionals to understand more about the value drivers of businesses, and for valuation professionals to use reported values as comparable data.  In the following article, the author argues in favor of an unprejudiced usage of fair value data on intangibles, in particular for trademarks and brands.

What and how is it reported?

[su_pullquote align=”right”]Resources:

On-Demand Webinar: What You Can‚Äôt See Has Value‚ÄĒThe Valuation Of Intangible Assets

On-Demand Webinar: Issues On Intangible Assets Recognition Upon Business Combinations

[/su_pullquote]

According to global M&A statistics, the number of corporate acquisitions total somewhere between 30,000 and 50,000 worldwide each year.  This range is likely underestimated for uncounted and unreported acquisitions.  The accounting treatment of most of these acquisitions follows IFRS 3/SFAS 141 and is called purchase price allocation (PPA).  All different intangible assets being part of the acquired business are valued and accounted according to fair value measurement standards.  The results of PPAs are then disclosed with different levels of detail in financial statements of the acquirers if they are listed companies.

Ideally, a PPA is reported separately in all its single elements, showing the full balance sheet of all assets including intangibles, liabilities, and purchase consideration paid.¬† Sadly, PPAs are often disguised, condensed, or broken up so that it is more laborious to reconstruct the full PPA, or even impossible.¬† Unfortunately, the results of PPAs disclosed in financial statements are often condensed horizontally (two or more PPAs summed up into one caption for all PPAs of the year or quarter); vertically (particular elements of a PPA combined, i.e., all different intangibles summed up in one single caption, ‚Äúother intangibles‚ÄĚ, or ‚Äútrademarks and patents‚ÄĚ); or broken up (when its elements are dispersed over different sections of the financial statement, or on different consecutive financial statements).¬† Leaving all this secretiveness apart, there are still between 1,500 and 2,000 PPAs worldwide each year disclosed in much detail.¬† Over time, this makes up for approximately 20,000 such detailed PPAs available in the public domain.¬† This set of data is much larger than, for example, royalty rates available from license agreement databases.

Fair value accounting is much better than its reputation

When it was introduced, fair value accounting under SFAS 141 and IFRS 3 came like a small revolution.  It was the result of a long and controversial debate and a compromise between the traditional views of historical cost based accounting against the modern, value-based view of accounting.  The basic idea was to take account of the increasing importance of intangible assets.  Fair value accounting required accountants to recognize assets based on their expected future earnings.  And, it fueled the rapid growth of the then young discipline of business valuation and its various professional credentials (i.e., CVA, ASA BV, CPA ABV, CBV).

But as stated above, fair value accounting was a compromise.  The naysayers were in a good position to contemplate various inconsistencies, disadvantages, and purported defects of fair value accounting and PPAs.  The following is a list of some of the purported defects of fair value accounting:

- PPAs were expected to reduce substantially the amount of acquired goodwill in favor of identifiable intangible assets. Notwithstanding the above, goodwill remains quite important; on average, goodwill accounts for fifty percent of enterprise value in PPAs.  That was criticized by many commentators.

- PPAs were suspected by many to be misused for creative and opportunistic accounting. In particular, filers were suspected to overvalue non-amortizable assets with indefinite lives (in particular, goodwill and trademarks) in order to increase income and earnings.  Another controversial topic under this headline is the reporting of bargain purchases from PPAs.

- Later, fair value accounting was blamed for having caused or accelerated the financial crisis in 2008/2009. Although PPAs have nothing to do with the marked-to-market accounting of financial instruments in banks, they were drawn into that debate.

- Regulators and standard setters found frequent non-compliance with disclosure rules. This related very much to the explanations provided with the PPA and to materiality issues, but less to the valuing itself.

- Some filers, in particular SMEs, complained about the costs related to PPAs and fair value measurement, and asked for relief and exemptions.

- When asked about PPA disclosures, some financial analysts commented that it is useless or even irrelevant information.

- Both, the IRS (Internal Revenue Service) and the OECD, addressed concerns with respect to the usefulness of purchase accounting for taxation purposes; in particular, with respect to intellectual property valuations, thereby pinpointing the subtle differences between fair value and fair market value (arm‚Äôs length) principles. Specifically, valuations of intangibles for allocation of purchase price should only be used as a “starting point” for transfer pricing purposes using caution and careful consideration of the underlying assumptions.

So, fair value accounting and PPAs had a tough time since their inception.  But despite all the naysayers, it is still there.  It was continuously adjusted and improved, and many of the critics proved to be wrong or exaggerated.  Like accounting and financial reporting will never be 100% perfect, the same is true for all of its elements, including PPAs; but it is the best solution we currently have.  In academic accounting research, it is undisputed today that detailed PPA disclosures are informative to investors and help to improve the quality of investment decisions, and that poor or abnormal PPA disclosures tend to cause negative stock market reactions.

Therefore, purchase accounting is much better than its reputation, and many analysts and investors appreciate it.  But what about valuators?  Can they benefit from previously reported PPAs, and how?  Yes, they could; but only a few of them do.  One reason for this is the controversial debate about purchase accounting.  But the major reason is that most of the valuation methods were essentially developed prior to the disclosure of PPA data, based on different data.

PPA disclosures are difficult to track

Many analysts and valuators, when confronted with a valuation or PPA, ask the question if there were similar acquisitions in the same sector in the past.  Almost always, the answer is yes.  But identifying such cases where the PPA was disclosed can be a long and frustrating exercise.  As stated above, between 1,500 and 2,000 PPAs every year are disclosed in detail.  Unfortunately, these cases are not only a small fraction of all acquisitions, they are also widely scattered across the financial statements of over 20,000 filing companies.  Matching M&A occurrences with PPA data is a tricky filter process.  First, not all M&A cases announced become effective.  Second, some acquirers do not file financial statements at all (i.e., private equity investors).  And third, many filers do not disclose PPA details.  On average, one must check twenty M&A cases to find one meaningfully reported PPA.  So most analysts or valuators are typically content with the P/E multiples, EBIT multiples, and revenue multiples filed from previous cases in specialized databases.  Few go beyond that and use PPA data as comparables in their valuations, either by locating relevant cases themselves or by using a PPA database.

PPAs provide the most meaningful comparables

The information they find in fully disclosed PPAs typically includes the following:

- nature of the acquired business and reasons for the acquisition

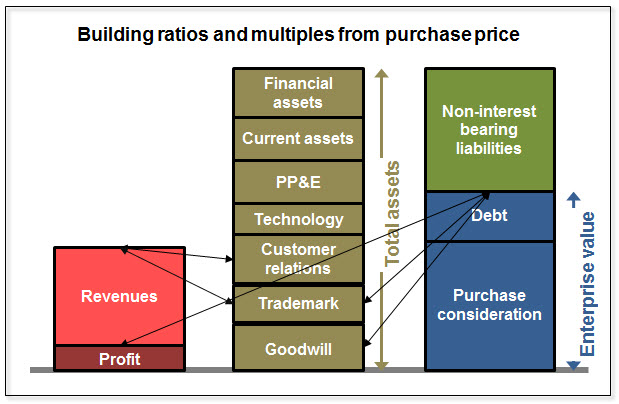

- balance sheet with all different assets, liabilities, and purchase consideration paid for the acquired business

- pro-forma revenues and profit of the acquired business

- remaining useful life for all the intangible assets reported

- valuation and amortization methods assumed for the intangibles

- discount rates and growth rates assumed in the valuation of the assets

- information on tax deductibility

It provides precise answers or indications to the following questions:

- What are the effective valuation multiples for the acquired business based on audited data?

- What is the structure of assets, and how does each asset contribute to enterprise value and future profits of the acquired business?

- What asset-specific profit margin on revenues is required for the acquired business, i.e., excess earnings margin for customer value or royalty rate for trademark value?

The valuator gets a range of values and parameters used in previous valuations.  This can be very meaningful and robust comparable data for upcoming valuations.  However, many valuators hesitate and raise various concerns.

Some people believe that PPAs in the same industry often rely on similar transactional data from the same license agreements, or from previous PPAs, resulting in multiple counting and convergence around a frequently observed mean value.¬† This concern is not confirmed from the results of industry specific PPA data, on the contrary.¬† Businesses, strategies, and profits in the very same industry are so different that the resulting PPAs, as well as the underlying valuation parameters, vary as accordingly and show high standard deviations around their median values.¬† In the watch industry, trademark royalty rates applied in PPAs vary from two percent to twenty percent on revenues.¬† Or from 0.1% to 3.25% for temporary staffing businesses.¬† A benchmarking of comparable data from PPAs provides no more than a range and a distribution of parameters for a particular industry, where the business for each data point is well described and comprehensive.¬† The valuator must then determine where to position its subject case within or next to this distribution, and why.¬† There is no risk of comparables leading to valuation convergence, unless the industry itself and its competition result in uniformity and commodities.¬†Some people believe PPA data is calculated or synthetic.¬† It is neither market based nor transaction based nor ‚Äúarm‚Äôs length‚ÄĚ, and therefore inapplicable in fair value valuations.¬† This is true for market based methods (i.e., relief from royalty), but not for income based methods (i.e., multi-period excess earnings).¬† This concern implies that royalty rate data from unrelated license agreements is pure market data.¬† A market implies several (potential) buyers and either an auction price or an equilibrium price.¬† But there is no active ‚Äúmarket‚ÄĚ for license rights; license agreements are often coincidental and very specific to the two contract parties, but likely irrelevant to others.¬† It implies further that comparable license agreements do exist, which‚ÄĒas most valuators of intangibles have experienced‚ÄĒis usually not the case.¬† And it implies, thirdly, that license agreements can be considered a ‚Äútransaction‚ÄĚ at all, and not only a temporary grant.¬† In contrast, a PPA implies the transfer of full and long-term ownership.¬† In this context of limited market based data, PPA data is certainly an option to consider.

People who believe that PPAs based on weak comparable data (i.e., from license agreements) must be even weaker neglect a couple of aspects.¬† First, a previous PPA may well include additional information and comparables not available in the public domain, thereby increasing its accuracy.¬† Second, a PPA makes‚ÄĒby its premise and nature‚ÄĒan adjustment for profitability to revenue based multiples (i.e., royalty rates).¬† This adjustment is otherwise called profit split.¬† The purchase consideration reflects total profits of the acquired business, and the sum of all assets must fit into this 100% threshold.¬† Third, a PPA is usually much more than a few stand-alone valuations of a few intangibles and the calculation of the remaining residual for goodwill.¬† It is rather a complex financial modeling with multiple interdependent input parameters, including asset-specific discount rates.¬† The various assets are valued and weighted relative to each other.¬† In the end, the valuation parameters for all different assets are adjusted to the reality of the subject case, and must add up to total revenue and profit projections, and overall WACC.¬† Although a royalty rate applied in a PPA valuation might differ from the sample of market comparables used, it is still robust and accurate for the particular case, for all the constraints and restrictions within the PPA.

Establishing comparability

Of course, not all PPAs are perfect.  Some PPAs, or their parts, must be considered outliers and abnormal, for various reasons.  Maybe the valuator was inexperienced or used weak comparable data.  Maybe the valuator was not fully independent and did creative valuing.  Maybe the acquisition itself was overpaid.  Abnormality is, however, not something specific to PPAs.  Statistically it occurs in data samples of any kind, and of course, it occurs in royalty rate databases as well.  The key questions are how often, and how to identify and exclude abnormal values.  With sufficiently large peer groups (ten data points and more) and statistical analysis (interquartile range, standard deviation) it is not too difficult to detect outliers.  Empirically, there are less outliers in PPA data than in license agreement data; PPA data must therefore be considered more robust.  Even more, PPA data contains more royalty rates below one percent (for weakly branded businesses) and above fifteen percent on revenues (for luxury brands and for very profitable consumer brands) where unrelated license agreements rarely exist for commercial and strategic reasons.

Comparability is important when using comparable data.  It depends on the choice (number of comparable cases available) and on the selection process.  Several aspects have to be considered to establish comparability:

- A grocery store is different from a department store. A retail bank is different from an investment bank.  And a software business selling millions of software packs to single persons at U.S. $19.90 each does not compare to a provider of software solutions to operate stock exchanges.  Therefore, sector comparability should be established at the most detailed sector level possible.

- Industries and sectors change over time with regard to their growth, profitability, and value drivers. Valuation parameters change, too.  Therefore, comparable data being more than ten years older than the subject case should be treated with care.

- A fashion business acquired for 2x annual revenues will have other valuation parameters than a similar fashion business acquired at 1x annual revenues, for their different profitability. While profitability should not determine the identification and selection of comparable cases, it should be considered to understand and explain the distribution of data points within the peer group.

- Sometimes, differences in valuation parameters occur for different territories. Basic food businesses (i.e., oils, sugar, pasta, biscuits) might be little sought after in developed countries, but highly profitable, fast growing, and attractive in emerging countries.  Or profitability of private hospitals is higher in open than in regulated markets.

PPAs are a most valuable source of comparable data for valuations.  Provided that comparability issues are properly considered, PPA data provides robust, meaningful, and comprehensive parameters for the valuation of intangible assets.  This can be used to complement or replace traditionally used data sources, like license agreements.

Christof Binder, MBA, PhD is Managing Partner of Markables, a Switzerland-based cross-border venture of experienced trademark experts who deal with the challenges of trademark valuation from different perspectives.

Dr. Binder acted as financial expert in trademark valuation, as well as in trademark infringement and transfer pricing litigation issues to courts and arbitration panels in Europe. He is a regular author and speaker on trademark licensing, royalty rate and valuation issues.

Dr. Binder can be reached at 41 (41) 810 28 83 or by e-mail to cbi@markables.net.