Valuation of Ambulatory Surgery Centers

In an Era of Reform: Value Drivers (Part II of II)

As stated in Part I of this II-part series, as the demand for healthcare services continues to grow, the site at which these services are performed is experiencing a simultaneous transformation from the inpatient (e.g., hospital) setting to the outpatient setting—e.g., at ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs). This article will review the unique value drivers that impact the typical valuation approaches, methods, and techniques that are often utilized in determining the value of ASCs in the current healthcare delivery system.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]Resources:

How to Value Physician Practices

The Four Pillars of Healthcare Valuation

Healthcare Industry—Trends, Analysis, and its Impact on Valuations

[/su_pullquote]

Introduction

As stated in Part 1 of this two-part series, as the demand for healthcare services continues to grow, the site at which these services are performed is experiencing a simultaneous transformation from the inpatient (e.g., hospital) setting to the outpatient setting—e.g., at ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs).[1] This article will review the unique value drivers that impact the typical valuation approaches, methods, and techniques that are often utilized in determining the value of ASCs in the current healthcare delivery system.

Value Drivers—Freestanding Outpatient Enterprises

While the value drivers identified for ASCs are similar to that of other healthcare outpatient enterprises, there are several specific dynamics related to ASCs and other freestanding outpatient enterprises that should be taken into consideration during the appraisal process.

Scope of Services

The scope of services provided by a particular freestanding outpatient enterprise is a key element impacting the overall indication of value attributed to that enterprise. For example, multi-specialty ASCs that have a higher percentage of orthopedic cases, which are reimbursed at more lucrative rates than gastroenterology cases, will generate larger amounts of revenue per case, typically leading to higher net economic benefit, and an increased value of the subject enterprise. Additionally, the diversification of services offered may lower the actual and/or perceived risk of investment in a particular ASC in contrast to the industry of freestanding outpatient enterprises and ASCs.

Advancements and trends in technology also impact the scope of services offered at ASCs. Potential services that may be provided at ASCs may include, but not be limited to, any of the following: (1) gastroenterology and endoscopy; (2) ophthalmology; (3) pain management; (4) dermatology; (5) urology; (6) podiatry; (7) orthopedics (including spine); (8) respiratory; (9) gynecology; (10) ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialty and procedures; (6) neurosurgery; (7) general surgery (including bariatrics); and (10) podiatry.

In addition to the added revenue opportunities created by expanding the scope of services, an ASC may be able to create value through economies of scale. As more revenue is produced by the additional services rendered, only the variable portion of each expense would increase, while the fixed portion would remain constant, thereby increasing the incremental benefit generated by each additional service. Note that this incremental benefit would only increase up to the point of capacity, where additional capital costs would reduce the benefit generated by the additional services.

Capacity

Capacity is another key element that impacts the value attributable to ASCs. One measure of capacity for ASCs is the amount of physical space utilized in the provision of services. For example, for an ASC, the number of operating rooms available, as well as average turnover rate, can be used as measures of capacity. These metrics can be compared to normative industry benchmark survey data related to comparable enterprises and ASCs.

Revenue Stream

Similar to that of physician professional practices, the main drivers of revenue for freestanding outpatient enterprises such as ASCs are:

- Changes in reimbursement yield, driven by trends in reimbursement from Medicare and private payors; and

- Changes in patient volume, which are based on:

- Changes in utilization demand for services; and

- Changes in the level of market shareof the subject enterprise.

As advancements in technology and an increased focus on cost reduction continue to drive U.S. healthcare delivery to the outpatient setting, the increased growth in the utilization of those services offered by ASCs and other freestanding outpatient enterprises will likely endure. The percentage of surgical procedures performed in the outpatient setting have grown slightly from the mid-1990s to 2016, from approximately 58% in 1995 to approximately 66% in 2016.[2]

As discussed in Part 1 of this series, most ASCs are primarily reimbursed under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) or at a percentage of the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) reimbursement rate. However, certain facilities are reimbursed under a different, or modified, payment system, which impacts the unit of productivity utilized to measure reimbursement yield, as well as the trends associated with the given reimbursement method. The payment system utilized is a key consideration when projecting revenue streams for the valuation of any type of freestanding outpatient enterprise.

Other considerations regarding reimbursement yield that are likely to impact the revenue streams of freestanding outpatient enterprises include:

- Bundled payment systems;

- Quality reporting programs;

- Method and frequency of rate updates, e.g., APC payments are based on the Consumer Price Index for all Urban Consumers (CPI-U), while similar hospital codes are updated based on the hospital market basket;

- Stability of payment rates, e.g., reductions in reimbursement to curb utilization and spending are applied more often to certain billing codes;

- Referring physician utilization trends, e.g., increased scrutiny of physician referrals under fraud and abuse laws may impact patient volumes; and

- Dependence on payor mix.

For ASCs, where reimbursement yield for certain services, e.g., surgical procedures, is subject to continuously changing payment rates, the projection of revenue streams by individual modality, instead of for the enterprise as a whole, may be more appropriate.

Although utilization of outpatient services has increased, outpatient enterprises (particularly ASCs) have experienced reductions in reimbursement yield, reducing their revenue growth. Despite this declining reimbursement yield, overall revenue for the ASC market was $27.5 billion in 2015 and is projected to continue growing at an annual growth rate of 6.3% from 2015 to 2020.[3] This trend is driven by the growth in the number of insured Americans; the aging population demographic; and a general increase in the amount of per capita disposable income.[4]

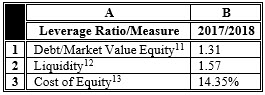

Payor Mix

The typical payor mix in 2016 for ASCs, by gross charges, is set forth in Table 1, below.

Table 1: Typical ASC Payor Mix [5]

It should be noted that the reimbursement yield of a given ASC is significantly impacted by whether the particular facility bills on an in-network or out-of-network (OON) basis for a particular insurance plan. Under certain insurance coverage plans, patients are given financial incentives, e.g., lower deductibles and co-insurance payments, to see providers that are considered to be “in-network,” referring to a contractual relationship entered into by the provider with the payor to offer services at a discounted rate.[6]In an effort to mitigate paying higher reimbursement ratesfor OON services, certain payors have instituted internal fee schedules that cap the allowable charge that these payors will reimburse providers for OON services .[7] However, it should be mentioned that certain states have limited the ability of certain commercial insurers to cap the reimbursement to non-participating providers.[8] These trends related to capping OON charges may result in a decreased reimbursement yield for those ASCs that rely on an OON strategy.

Operating Expenses

The operating expenses of each ASC are dependent on the specialty, or modality, practiced within the ASC. Accordingly, those ASCs that utilize sophisticated technologies typically incur higher operating expenses, where the economic cost burden associated with the capital utilized is included in the operating expenses (either through depreciation, lease expense, or both). While higher costs typically indicate lower value, it should be noted that ASCs that utilize more sophisticated technologies may be able to increase market share, and therefore, from a financial economic perspective, the costs of these technologies must be weighed against any future benefits when assessing the value proposition of new technology and the impact it may have on the value of that ASC.

In addition to equipment and technology costs, there may be significant human resources/personnel costs(wages and benefits) associated with the staff required to operate ASCs, e.g., non-physician ancillary service providers (mid-level providers, technicians, and paraprofessionals), and administrative staff; and in ASCs, these staffing costs may represent the largest operating expense incurred by the organization.

Additional considerations regarding the operating expenses incurred by an ASC include:

- The size of the facility, e.g., the number of operating rooms and the number of cases;

- The ability of the ASC to manage supply costs;

- Whether the center directly employs or contracts with anesthesiologists;

- Whether the management of an ASC is performed by a third party; and

- Whether the ASC employs a medical director.

In addition to the types of operating expenses incurred by an ASC, the amount of fixed and variable expenses should be considered when performing an appraisal, as each type of expense is projected differently.

Similar to trends impacting other healthcare entities, ASCsmay benefit from increased utilization of administrative related technology, e.g., electronic health record (EHR) systems, which can reduce the economic operating costs associated with the provision of administrative tasks and duties.

Capital Structure

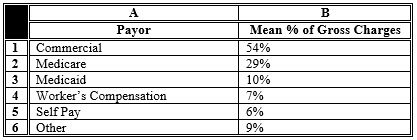

The implications of the capital structure decision for ASCs are like that of physician professional practices. These implications include: (1) the mix of debt and equity financing affects the risk-adjusted required rate of return for investment in the subject enterprise; (2) debt financing is typically cheaper than equity financing; and (3) financing costs reflect the risks associated with each type of capital provided, e.g., debt financing typically considers the four C’s of the obligor, i.e., credit risk (default risk) of the borrower, capacity of the borrower to make timely repayments of both principal and interest (short term liquidity and interest coverage), collateral to cover the lender in case of borrower default, and an analysis of the covenants included in the indenture agreement;[9] and, equity financing considers the risks associated with an investment in the residual ownership interest (subordinate to any debt holders) of the subject enterprise. Various metrics describing the capital structure of freestanding outpatient enterprises are presented below in Table 2.

Table 2: Examples of Leverage Ratios for Outpatient Facilities [SIC 8093][10]

Note that the amount of debt utilized by a specific freestanding outpatient enterprise will likely be impacted by: (1) the age of equipment and other technology utilized by the enterprise; and (2) the enterprise’s dependence on technology, e.g., an ASC will have higher capital needs related to obtaining and maintaining surgical equipment.

Data and information pertaining to the most probable capital structure of an ASC can be derived from normative industry benchmark survey data, as well as from comparable publicly traded company data, for those ASCs that have comparable publicly-traded companies. Additionally, the capital structure can be determined through techniques such as the iterative method. For the purpose of establishing the fair market value of an ASC, it is important to utilize formulas based on market values of equityand debt, rather than book values.[14]

Suppliers

The greater amount of bargaining power that an enterprise commands in the marketplace, the higher the value the organization can create through the supply chain, ceteris paribus. In general, enterprises achieve a significant amount of their bargaining power from their size, since larger enterprises, with greater patient populations, represent a larger portion of business for vendors, and therefore, have more negotiating power than smaller enterprises. In addition, those larger outpatient enterprises that are able to reap the benefits of this increased market leverage may be able to lower operating costs by negotiating lower supply prices, thereby improving profit margins, which may increase the indication of value of the enterprise. It is this trend that is driving, in part, the growing number of ASCs that are acquired or integrated with larger hospital or health system partners.[15]

Subject Entity Specific/Non-Systematic Risk

While an investor in an ASC would have additional investment opportunities available to them, e.g., government bonds and equity indexes, the discount rate utilized to convert all the expected future net economic benefits to present value should consider these opportunity costs, as well as any idiosyncratic risk associated with an investment in the specific subject enterprise. Subject entity specific/non-systematic risk factors for most ASCs include, but are not necessarily limited to:

- The uncertainty related to the continuity of the projected revenue stream based on the probability of achieving the projected productivity volume and the efficacy of the projected reimbursement yield utilized in the analysis;

- The risk related to the probability of achieving industry indicated operational and financial benchmarks utilized in the analysis;

- The competitive marketplace within which the ASC operates; and

- The historical operations of the ASC as compared to industry benchmarks.

Examples of subject entity specific/non-systematic risk considerations related to the valuation of an ASC, include, but are not necessarily limited to:

- The diversity of specialties and services offered at the enterprise being valued;

- The percentage of OON patient volumes;

- Capital needs related to the facility and equipment;

- Operating performance;

- The stability and relative size of current and future reimbursement revenues; and

- The relationship with independent surgeons/referring physicians in the market service area of the subject enterprise.

Conclusion

The value of ASCs is closely tied to their ability to operate in a continuum of care in this new value-based reimbursement paradigm, which may determine their viability as an ongoing enterprise in the future. The overall healthcare transactional market is likely to continue experiencing increased transactional activity as a result of healthcare reform initiatives, as physician practices, and other outpatient enterprises, e.g., ASCs, participate in such integration activities as ACOs, medical homes, and co-management arrangements, and as the shift continues from providing care in an in-patient setting to providing more care in the out-patient setting.

[1] “Hospitals: Origin, Organization, and Performance” in “Health Care USA: Understanding its Organization and Delivery” By Harry A. Sultz and Kristina M. Young, Sixth Edition, Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2009, p. 75, 103; “Ambulatory Care” in “Health Care USA: Understanding its Organization and Delivery” By Harry A. Sultz and Kristina M. Young, Sixth Edition, Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2009, p. 121–124.

[2] “Chart 3.11: Percentage Share of Inpatient vs. Outpatient Surgeries, 1995–2016” in “Trendwatch Chartbook 2018” American Hospital Association, 2018, p. 34.

[3] “IBISWorld Industry Report OD5971: Ambulatory Surgery Centers” By Sarah Turk, IBISWorld, May 2015, p. 4.

[4] Ibid, p. 5–6.

[5] “Intellimarker: 2018 Multi-Specialty ASC Benchmarking Study” VMG Health: Dallas, TX, 2018, available at: httpshttps://intellimarker.com/content/intellimarker/Payor_Mix_-_Charges/ (Accessed 9/20/18).

[6] “Healthcare Finance: An Introduction to Accounting and Financial Management, Third Edition” By Louis C. Gapenski, Third Edition, Chicago, IL: Health Administration Press, 2005, p. 38; “Introduction to Health Services” Seventh Edition, Stephen J. Williams and Paul R. Torrens, eds., Clifton Park, NY: Thomson Delmar Learning, 2008, p. 124.

[7] “ASC and Payor Negotiations” By Gary Scott Davis, Kriste Goad, and Naya Kehayes, McDermott Will & Emery, 2012 ASC Symposium (2012), http://www.mwe.com/info/ASC/2012materials/Operations-Administrative/ASC-Payor.pdf (Accessed 4/4/18); and, “Health Plans Seek Leverage When Physicians Submit Extremely High Bills” By Joseph Burns, Managed Care, August 2011, http://www.managedcaremag.com/archives/1108/1108.gouging.html (Accessed 4/4/18).

[8] “DOBI levies nearly $9.5 million in penalties against Aetna Health” By State of New Jersey Department of Banking and Insurance, July 25, 2007, http://www.state.nj.us/dobi/pressreleases/pr070725.htm (Accessed 4/4/18).

[9] “Fixed Income Analysis for the Chartered Financial Analyst Program” By Frank Fabozzi, PhD, CFA, Second Edition, 2005, p. 572.

[10] Data for SIC code 8093 was used when possible, otherwise, SIC code 809 and NAICS code 621493 were utilized.

[11] Calculated as an average for “Total liabilities: Net Worth” from the following sources: “Industry Financial Report: ALL US [621493]” Bizminer, December 2017, p. 6; “Summary [621493]” RMA Annual Statement Studies 2017–2018.

[12] Calculated as an average for “Current Ratio” and “Quick Ratio” from the following sources: “Industry Financial Report: ALL US [621493]” Bizminer, December 2017, p. 6; “Summary [621493]” RMA Annual Statement Studies 2017–2018.

[13] Calculated for SIC code 809 using Duff & Phelps Cost of Capital Navigator, available at: https://costofcapital.duffandphelps.com/landing

[14] “Cost of Capital: Applications and Examples” By Shannon P. Pratt and Roger J. Grabowski, Third Edition, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2008, p. 276–77.

[15] “IBISWorld Industry Report OD5971: Ambulatory Surgery Centers” By Sarah Turk, IBISWorld, May 2015, p. 8.

Todd A. Zigrang, MBA, MHA, CVA, ASA, FACHE, is president of Health Capital Consultants, where he focuses on the areas of valuation and financial analysis for hospitals and other healthcare enterprises. Mr. Zigrang has significant physician-integration and financial analysis experience and has participated in the development of a physician-owned, multispecialty management service organizations, and networks involving a wide range of specialties, physician owned hospitals, as well as several limited liability companies for acquiring acute care and specialty hospitals, ASCs, and other ancillary facilities.

Mr. Zigrang can be contacted at (800) 394-8258 or by e-mail to tzigrang@healthcapital.com.

Jessica Bailey-Wheaton, Esq., is Vice President and General Counsel for Heath Capital Consultants where she conducts project management and consulting services related to the impact of both federal and state regulations on healthcare exempt organization transactions, and provides research services necessary to support certified opinions of value related to the Fair Market Value and Commercial Reasonableness of transactions related to healthcare enterprises, assets, and services.

Ms. Bailey-Wheaton can be contacted at (800) 394-8258 or by e-mail to jbailey@healthcapital.com.