The Future of the Business Valuation Profession

(Part IV)

To look to the future of the BV profession, we must explore the relevant dynamics within the industry. That starts with looking to our past to see what events and milestones brought us to where we are today, followed by ascertaining the economic and demographic trends leading us into the future, and culminating with identifying those trends which will have the greatest impact upon the profession. NACVA set upon drafting a white paper that would provide valuable insight to the future of the business valuation profession, with Chris Mercer taking the lead who is known by nearly every person in the valuation industry.

Trends in Valuation Theory

Past Practices

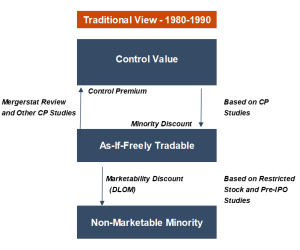

In the author’s opinion, many business valuators have been reluctant to move beyond past practices. Many valuators came into the profession in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s when three conceptual levels of value were perceived as shown in the following figure.[1]

During this time, the rules of the game were simple for operating entities. Calculate a value using the guideline public company method, which was referred to as the “as-if-freely tradable” value, and add a control premium of typically 40%, plus or minus (from available control premium studies) to obtain a control value. However, if use of public company multiples yielded control (financial) values, the addition of a 40% control premium often led to significant overvaluation of companies at the control level of value.

Alternatively, practitioners would develop a value at the as-if-freely-tradable level and would typically subtract a marketability discount of 35%, plus or minus, to reach the non-marketable minority level of value. The marketability discounts, or discounts for lack of marketability (DLOMs) were based on a handful of already dated restricted stock studies and were bolstered by a few studies of pre-IPO discounts. These studies had a range of averages or medians that clustered around 35%, which became the default discount.

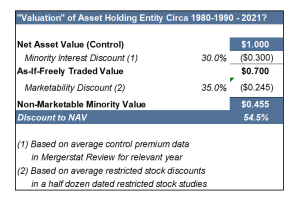

With asset holding entities, for nonmarketable minority valuations the established methodology often led to ridiculous results. For control value, net asset value or the market value of an entity’s assets less its liabilities was considered the proper approach. With the control value in hand, the established methodology was to then apply a minority interest discount for a minority interest.

As seen in the figure above, because the control value incorporates a control premium, the valuator needs to remove it to yield the as-if-freely traded value, a necessary step before applying a 35%, plus or minus, marketability discount typically derived from restricted stock studies, all in order to reach the non-marketable minority value.[2]

The common practice from the 1970s to the 1990s of applying consecutive minority interest and marketability discounts for asset holding entities often led to very low valuations for non-marketable minority interests. For example, this “valuation” of an asset holding entity would turn $1.00 of net asset value (NAV) into about $0.45 of non-marketable minority value as seen below:

If valuators inflated the minority interest and marketability discounts, the discounts to derive net asset value became even higher resulting in even lower net asset value (NAV). In this simple example, the discount to NAV is about 55%.

Looking Forward

Something was missing from this traditional view towards valuation that, to some degree, persists to the present day among many valuators. The missing element is (was) that there is little consideration of the basics underlying the valuation, which form the heart of an integrated theory of business valuation (a topic of which this author has published a book of the same title). The theory is as follows:

- The value of a business is the present value of its expected cash flows and the growth of those cash flows into perpetuity. The present value is determined by discounting all expected future cash flows to the present at a discount rate reflective of the risks associated with achieving those cash flows.

- The value of an interest in a business is the present value of the expected cash flows and the expected growth of those cash flows to the interest held over an expected holding period for the interest. The present value is determined by discounting all expected cash flows to the interest over the expected holding period, including a terminal value, to the present at a discount rate reflective of the risks of achieving those cash flows. This discount rate is referred to as the required holding period rate of return.

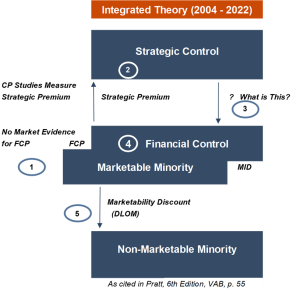

This author published the first edition of Business Valuation: An Integrated Theory in 2004.[3] The book introduced the Integrated Theory and with better defined (in the author’s opinion) levels of value (depicted in the figure below) than that shown in the Traditional View chart previously depicted.

The following observations are noted as we compare the levels of value chart of the Integrated Theory above with the Traditional View first depicted above. The numbered paragraphs refer to the corresponding numbers on the chart above.

- The “base value” is that of financial control/marketable minority value. The great majority of public companies do not get acquired in any given year. This suggests that most companies are trading at their financial control values, which are the functional equivalent of the marketable minority values. For this reason, the levels of value chart of the Integrated Theory reflect overlapping synchronous values.

- Most observed change of control transactions are based on an acquirer’s view of the strategic or synergistic benefits to be derived from acquiring a target company. These benefits come in the form of expected enhanced cash flows (synergies) or reduction of risk with the newly combined entity, or other expected strategic benefits. They do not reflect the so-called “prerogatives of control” that valuators for years have used as reasons for minority interest discounts.[4]

- The implications of #1 and #2 above are that strategic control premiums do not provide a means for estimating minority interest discounts.

- There is no market evidence for financial control premiums over the publicly trading prices of public companies.[5]

- When the financial control/marketable minority value is the base value for examining nonmarketable minority value, there is no application of a minority interest discount. Logically, the appropriate discount is the marketability discount, which should be based on differences in expected cash flows of the business and expected cash flows to the interest being valued, as well as on differences in the risks of achieving the respective cash flows. Cash flows to an interest are often less proportionately than expected cash flows of the business. The risks of illiquid minority interests are often greater than the risks of the business. Both factors contribute to the existence of marketability discounts when valuing illiquid minority interests of closely held companies.

What was wrong with the traditional analysis throughout the 1970s–1990s is there was either no discussion or little focus on the characteristics of the investment, and no focus on the expected cash flows of the interests being valued, risks associated with achieving those cash flows, and the expected growth of those cash flows.

Predictions for the Future of Business Valuation Theory

Based on this brief discussion of the Traditional View of business valuation and the Integrated Theory, this author offers several predictions regarding the development of valuation theory over the next five to ten years.

To learn more about the business valuation profession and what the future holds, click here.

Â

[1] Adapted from Mercer and Harms, Business Valuation: An Integrated Theory (Hoboken, NJ, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2021), p. 249.

[2] The following quote from Shannon Pratt’s first edition of Valuing a Business in 1981 describes the methodology still used by many business appraisers today:

“The four studies discussed [early restricted stock studies] are quite consistent in indicating an average discount for lack of marketability of approximately 35 percent for restricted stocks of publicly-traded companies. Most such securities eventually will be registered and become freely tradeable. Shares of closely-held companies, most of which will never be freely tradeable, suffer more from lack of marketability than do restricted shares of publicly-traded companies. Once the analyst has made his best estimate of the price at which the shares involved in the valuation would sell if they were freely marketable, the discounts at which restricted securities of publicly traded companies sell can provide useful guidance to determine an appropriate marketability discount.”Â

Pratt, Shannon P., Valuing a Business (Homewood, IL, Dow-Jones – Irwin, 1981) p. 155.

[3] Mercer, Z. Christopher, The Integrated Theory of Business Valuation (Memphis, Peabody Publishing, LLC, 2004). The title was changed to Business Valuation: An Integrated Theory in subsequent editions. The current reference is Business Valuation: an Integrated Theory Third Edition (Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2020). See its Chapter 3, “The Integrated Theory (Equity Basis).”

[4] This concept is clearly recognized in Valuations in Financial Reporting Valuation Advisory 3: The Measurement and Application of Market Participant Acquisition Premiums, which was published by The Appraisal Foundation in 2017.

[5] The possible exception to this statement can be found in the shares of publicly traded closed-end funds, which often trade at modest discounts to their net asset values.