Case Study

Creative Cash Flow Analysis for Bankruptcy Assignment

Earlier this year, the author received a business bankruptcy assignment which called for assessing the cash flow for a particular asset in a bankrupt estate and how the circumstances of the estate affected the value of that particular asset. As this assignment continued through testimony and the judge’s ruling, the author wanted to share his experience.

While working as an economic expert, I receive numerous assignments in the areas of personal damages, commercial damages, and business bankruptcy. While the assignments for personal and commercial damages cover the waterfront for forensic economic analyses, they have similar aspects in common. One party has claimed the other wrongfully damaged them. From that wrongful act, income has been lost. The injured party may or may not be offsetting the loss by generating income since the alleged wrongful act. The post injury income, if any, must be used to offset the estimated loss. And, if the losses occur in the future, they must be discounted to present value.

The assignments for business bankruptcy do not fall in this vein. They are generally related to assessing the value of the business in bankruptcy, the (cramdown) interest rate to be paid on prepetition secured debt after the restructuring plan has been approved and/or creating or assessing the pro-forma cash flow analysis for the first five years of operation once the business moves out of its Chapter 11 protection.

Earlier this year, I received a business bankruptcy assignment which called for assessing the cash flow for a particular asset in a bankrupt estate and how the circumstances of the estate affected the value of that particular asset. This assignment included me testifying at a lift stay hearing in which the secured creditor, a Texas bank, would ask the judge to lift the stay which, under Chapter 11 bankruptcy, prevents a creditor from foreclosing and seizing property or assets of the debtor. If successful, the bank would then foreclose on the property and take control of its management and subsequent sale.

The Circumstances of the Estate

The bankrupt estate was a series of LLC real estate holdings. The owner owned a number of real estate properties and created LLCs for each property. Almost all of these properties were houses or small apartment buildings which were rented to students at the University of Texas at Austin. Of these properties, five were part of the bankrupt estate.

All these properties were used for student housing. The largest of the properties was the one I was asked to assess. The property itself, which was called The Outlaw, was a three-story building which sat approximately three blocks from the northern end of the UT-Ausitn campus. The owner bought the property in 2020 and construction on the apartment building began in 2021.

The building, when completed, was to house 66 students. The second and third floors were divided into suites, some with four residents, some with three, others with two. In each suite there were individual bedrooms and baths for each resident. On the first floor, there was to be a lobby area, management and leasing offices, and a convenience store. The parking garage for residents was below the building.

The City of Austin allows for not only a Certificate of Occupancy for completed buildings but also a Temporary Certificate of Occupancy for buildings that have a portion of its building completed and occupiable but other parts needed to be completed. The City of Austin granted a Temporary Certificate of Occupancy for the top two floors in late 2024. Such were the circumstances for this building when I received the assignment in 2025.

Nature of the Estate

Soon after the construction on the building began in 2021, the owner and the construction company began to fight. This was a time when global supply chains were delayed and the price for many goods, including construction materials, increased. This was true with the construction materials for the building of The Outlaw.

The owner became angered by cost increases and construction delays. Ultimately, she canceled the construction contract and hired another firm to finish the work in 2023. The originally hired construction contractor sued for breach of contract and lack of payment. The case went to arbitration and the construction contractor was awarded $1,040,000. The construction company then placed a mechanic’s lien on the building which was still in place in 2025.

In March 2025, I went to Austin on separate business but made time to visit the apartment building. On my visit, I found no management on site and therefore was not able to go inside. The grass and vegetation had not been mowed in weeks. The building and surrounding electrical boxes had been tagged with graffiti. And the area for the lobby convenience store was not completed and contained building materials.

I used my cell phone camera to record the status of the building when I visited. These photos became part of the evidence at the lift stay hearing in June 2025.

In December 2024, the owner stopped making payments on the bank loan which had funded the construction. As a part of the settlement offer in the restructuring plan, her husband, the owner of a very successful oil field service company, offered to start making the monthly payments and send in payments covering all of the prior six months’ monthly payments.

The bank had called the note on the property in March 2025. They wanted full payment or the ability to foreclose and claim the property. By the time we went to the lift stay hearing, the outstanding debt for the building loan was $7.6 million. This did not include the mechanic’s lien for over $1 million.

Feasibility

A feasibility study is a detailed analysis that assesses a proposed project’s practicality and likelihood of success. The question posed by economic or financial feasibility studies is, “Will the project’s projected benefits outweigh the costs and is the return on investment sufficient?”[1] My assignment was to project the future annual cash flow and see if it was sufficient to cover debt and operating expenses.

Although the owner’s husband had agreed to guarantee payments on the bank note, the bank was concerned that the debt was too high, and the mechanic’s lien clouded the title. They wanted to take control of the property, settle with the construction company, and sell the property to get it off their books.

In 2022, an appraisal by Stouffer & Associates in Austin Texas arrived at the following values for the property.

Valuation Scenarios:[2]

As-Is 2/2/2022 $ 5,790,000

As-Complete 3/2/2023 $11,880,000

As-Stabilized 9/2/2023 $12,000,000

According to the appraisal, the property would be stabilized when it reached 97% occupancy. “With consideration given to the market indications, the core location and smaller size (20 units), the occupancy levels of the comparables, we have concluded on a stabilized occupancy level of 97% or a vacancy rate and collection loss rate of 3.00%.”[3]

At the time of my assignment, The Outlaw had eight tenants renting for the next school year (2025–26). As the summer is the key time for leasing apartments to college and graduate students (because they lease from August to July), The Outlaw had only two months to rent out its remaining 58 bedrooms.

Having never operated for a full year and not being completed, there were no financial records showing annual lease revenue and costs. Monthly data was limited because the owner had combined some of the cost data with other properties she owned and managed. Therefore, I had to start assessing the property’s annual cash flow with a clean slate.

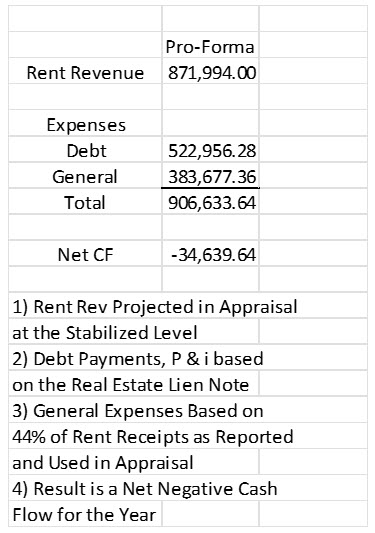

To begin my cash flow analysis, I reviewed what they were charging to rent a bedroom space in each suite. I then estimated what the annual income would be for 100% occupancy and then reduced the total by 3% to arrive at the stabilized level discussed in the appraisal.

The next step was to begin assessing the out-of-pocket costs to be incurred by this particular property. I obtained a copy of the amortization schedule from the bank. From that, I was able to calculate the annual debt service to be paid.

I researched the Travis County Appraisal District website to determine the annual ad valorem taxes to be paid. The City of Austin had assumed the property would be completed at the beginning of 2025 and had taxed the building at a value of $6,847,500. The bank believed this figure was somewhat greater than the building’s value and the owner argued that the property was worth more than $1 million.

Because the building was not complete, an appeal could be made to the Appraisal District to reduce the value and therefore, the amount of property taxes. For this reason, I did not include the ad valorem tax amount calculated by the Travis County Appraisal District.

Then, there were the general expenses. These would include marketing and management of the property, utilities, maintenance, groundskeeping, cleaning, etc. The property had only leased a few units and the owner had planned to but had not hired subcontractors or private firms to handle the day-to-day duties for managing the property. Therefore, there were no records showing costs.

The 2022 appraisal relied on statistics for five similar privately owned student housing facilities located near The Outlaw’s location. Their findings showed dollar and percentage costs figures. For my cash flow assessment, I relied on the percentage of costs to revenue for stabilized locations. This amount was 44%. This covered general and sales expenses. It also included an estimate for ad valorem taxes. The percentage did not include depreciation and/or amortization as this was a cash flow analysis and not estimating profits for an income statement.

The resulting simplistic estimated cash flow appeared this way:

The four shown notes were attached to the spreadsheet of my figures and presented to the court as a summary of my feasibility analysis. The conclusion was the property could not cash flow by itself. Without outside help, it would not be able to make its debt payments and cover its expenses annually under current circumstances.

Hearing and Decision

On June 2, 2025, the court held the hearing. It was a day long hearing. After brief opening remarks, the owner testified for the remainder of the morning. She blamed the builders and the bank for the delays for her defaulting. After lunch, a representative of the bank testified. He stated that over the past 15 years, he had made loans, but of lesser amounts, for her to purchase and upgrade or to build student housing in Austin. This was the first loan to have such problems and go into default. The only other witness was a representative for the construction company who testified his firm supported the bank’s request to lift the stay and allow the bank to foreclose.

I took the witness stand around 3:30 in the afternoon and testified until 4:30 just before the hearing ended. During my direct, I provide answers that explained my efforts similar to my discussion in this article.

On cross examination, the debtor’s attorney asked me if I had worked for the lead attorney in the past. I answered, “Yes.” Further questioning showed that I had worked as an expert for the debtor in my last assignment with him. This helped show that both of us have worked for both sides, debtor and creditor.

The attorney questioned my concerns about being able to achieve 97% occupancy before the end of August. He said that they have two months and the owner had hired a leasing company to market and lease the apartments. I stated that it would help but the building is not finished. The first floor continued to have building materials in the common area and the street presence was bad due to no lawn care for two to three months, and the graffiti. He argued that all of that could be fixed as soon as the judge decides not to lift the stay.

He did not question my revenue calculation, nor did he question my calculation for the annual debt payment. He questioned my use of the 44% factor for general expenses. I explained that the appraisers were detailed in the data gathered from the five comparative student housing locations and that they provided the best data available concerning costs. The attorney then asked why I did not use current data. I said because it was not available and would only apply to the building due to its limited occupancy.

The attorney then asked why I did not call the owner and get the information from her. He said, “Wouldn’t you have liked to talk with her”? I answered, “Yes.” But it is my understanding that I could not call her because that would be “ex parte” communication, which is not allowed. His response was, “Yes, that would be right.”

On redirect, my attorney asked me how this property affected the bankrupt estate. I responded that it was a weight or anchor on the estate. The other properties appeared to have positive cash flows. Were this property to remain in the estate, money from the positive cash flowing properties would have to be taken to make up for the shortage. In my opinion, the bankrupt estate would be better off without this property.

I waited in the courtroom until the judge ended the hearing. Before it ended, the senior attorney for the firm hiring me rested the creditor’s side of the case. He started to make an unofficial closing, but the judge shut him down. The judge said, “Did you not hear your expert? The estate would be better off without this property. You don’t need to say anything else.”

The debtor had one witness that was to testify a week later at an abbreviated hearing. He was a real estate broker from the Austin area and was to testify as to the value of the property. I was not in attendance for his testimony.

Soon after the closing of the testimony of the final witness, the judge ruled that the stay would be lifted, and the bank could begin foreclosure on the property. The attorneys hiring me were very pleased with the results and said the judge cited some of my testimony in his decision.

Conclusion

This case provided an unusual situation in which the expert had to become creative in assessing the feasibility of the debtor to create a positive cash flow to service its debt and pay for expenses. While historical data did not exist and current data were very limited, information existed to allow for piecing together an approach for showing the court why I believed the property could not service its debt and meet its expenses even when stabilized with 97% occupancy.

It was a challenge to take the assignment but very rewarding when my work was accepted by the court and provided a foundation for its decision. I wanted to share these results so that others might not shy away from a challenging assignment but rather put on their thinking caps and derive various means for addressing the assignment at hand and still meet the standards set by the courts.

[1] Feasibility Study, AI Overview w/ Google, www.google.com, Investopedia, www.investopedia.com

[2] Stouffer and Associates, Appraisal and Valuation Analysis, 2/7/2022, Proposed Student Housing Property, Austin Texas, p.2.

[3] Ibid., p. 88.

Allyn Needham, PhD, CEA, is a partner at Shipp Needham Economic Analysis, LLC, a Fort Worth-based litigation support consulting expert services and economic research firm. Prior to joining Shipp Needham Economic Analysis, he was in the banking, finance, and insurance industries for over 20 years. As an expert, he has testified on various matters relating to commercial damages, personal damages, business bankruptcy, and business valuation. Dr. Needham has published articles in the areas of financial and forensic economics, and provided continuing education presentations at professional economic, vocational rehabilitation, and bar association meetings. In 2021, Dr. Needham received a NACVA Outstanding Member Award. He is also a member of NACVA’s QuickRead Editorial Board.

Dr. Needham can be contacted at (817) 348-0213 or by e-mail to aneedham@shippneedham.com.