Valuing S Corporations in Family Law Engagements

Beyond an all-or-nothing approach

This overview examines the circumstances under which S corporations may or may not be tax affected. Particular emphasis is placed on family law engagements, which do not always involve a consistently defined standard of value, which creates much confusion for valuation analysts.

Valuing S Corporations in Family Law Engagements

Tax treatment of S corporations is a heavily debated topic within the valuation profession. The courts have ruled both that (1) under certain circumstances, it is appropriate to tax affect S corporations, and (2) under other circumstances, it is not appropriate to tax affect S corporations—each under a different premise of value.  Family law engagements do not always involve a consistently defined standard of value.  This factor can cause confusion among valuation analysts.  In the case of Bernier v. Bernier, the tax treatment of an S corporation and the standard of value were important issues.  The case was originally tried in 2003, where it was ruled that the S corporation subject to the dispute should be tax-affected at a hypothetical C corporation rate.  The case was appealed and remanded.  On remand, the instructions given by the Massachusetts Supreme Court were interpreted differently by all involved.  In 2012, the case was again appealed and remanded.

Introduction

Valuation analysts often debate the tax treatment of an S corporation.  Tax-related judicial precedent  have considered S corporation tax-affecting differently than judicial precedent related to shareholder oppression and marital dissolution. Valuation engagements in family law can be challenging.  This challenge is due to of the following factors:

- The standard of value definition is different for each state.

- The standard of value is not always clear and sometimes has to be interpreted from precedent setting cases.

This discussion, by reviewing Bernier v. Bernier (“Bernier”),1 considers the origination of S corporations and reviews how the standard of value—as it pertains to the judicial definition of standard of value—can affect the tax-affecting of S corporations for marital dissolution engagements. Bernier includes three different trials, each of which is discussed in detail.

This discussion is not intended to define the correct method to apply when tax-affecting an S corporation’s benefit stream.  Rather, this discussion analyzes the courts’ viewpoints on standard of value and tax-affecting S corporations for marital dissolution purposes.

The Background of the S Corporation

Before Congress created S corporations, businesses could elect to be either of the following:

- A C corporation that offered limited liability, but paid two levels of taxes—corporate income and dividend.

- A partnership or sole proprietorship that only paid a single tax—personal tax—but had unlimited liability.

Both of the available options were not ideal for small businesses. Â Small businesses either faced a double taxation or unlimited liability, both of which made it harder to compete with larger companies. Â In 1946, the Department of Treasury proposed the concept of creating an entity that had both (1) a single layer of federal tax, and (2) limited liability protection.

During this same time, President Eisenhower was coming under fire because much of the economic power was held by a few wealthy multinational corporations. Â In response to those concerns, President Eisenhower recommended the creation of a small business corporation. Â In 1958, Congress created subchapter S of the Internal Revenue Code.

In exchange for the benefit of paying a single tax, individuals electing the S corporation status agreed to the following limitations:2

- Be a domestic corporation

- Have only allowable shareholders—individuals, certain trusts, and estates, and may not include partnerships, corporations, or nonresident alien shareholders

- Have no more than 100 shareholders

- Have one class of stock

- Not be an ineligible corporation (i.e., certain financial institutions, insurance companies, and domestic international sales corporations)

It should be noted that the S corporation was created to provide a benefit to small businesses—single tax and limited liability.  The question is:  is there an actual benefit or just a perceived benefit, and if an actual benefit is realized, to what extent?

Since the creation of subchapter S, S corporations have grown to be one of the most common business structures. Â In 2009, the service estimated there were 4.1 million S corporation owners, more than twice the number of C corporations.3

The creation of S corporations has created one of the more controversial subjects within the business valuation profession: do S corporations deserve a price premium?

In the beginning, S corporations were valued the same as C corporations—that is, the income stream was tax-affected using C corporation rates.

In 2001, this topic received attention when the Sixth Circuit, in Gross v. Commissioner,4 opined that an S corporation’s benefit stream should be tax-affected at the entity level, but at a zero percent rate.

Since then, other courts have followed suit and created a debate between valuation professionals and the courts. Â Today, we find that, depending on the purpose of the valuation, certain courts tax-affect S corporations differently. Â This can create confusion and cause improper application of both premiums and discounts within marital dissolution engagements.

Bernier v. Bernier

In the case of Bernier, this very thing happened.  This case started in 2000 when the husband and wife both filed for divorce. The case was tried in probate court in 2003 (“Bernier I”).5

The wife appealed to the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts. The case was argued in 2007 (“Bernier II”)6 where the case was remanded with orders to adopt the metric employed in Delaware Open MRI Radiology Associates v. Kessler (“Kessler”),7 discussed below.

On remand, both the husband’s and wife’s experts implemented their version of the Kessler metric, but using two different tax rates.  The case was appealed to the Appeals Court of Massachusetts (“Bernier III”),8 and was argued in 2012 where it was remanded once again.

During the marriage, the couple acquired a large amount of real estate, a horse farm, and two supermarkets. Â The two supermarkets were equally owned by the husband and wife and needed to be divided within the marital estate. Â The husband and wife both retained valuation analysts to value the supermarkets and both came up with markedly different answers.

The valuation analysts on both sides agreed to the following:

- The buyer of the supermarkets would seek a yield that would equal the required rate of return.

- The most accurate estimate of the supermarkets’ value would be achieved using the Income Approach; a majority of cases pertaining to tax-affecting use the Income Approach.

The husband’s analyst estimated the value of the two grocery stores to be $7.85 million. The wife’s analyst estimated a value of $16.40 million.  The large difference in value was primarily due to the following factors:

- Standard of value

- Tax affecting benefit stream of an S corporation

- Application of a key man discount

- Application of a discount for lack of marketabilityÂ

The following section reviews each of these topics throughout the span of the case.

Standard of Value

The problem of defining value, for the many practical purposes for which the term is used, is an exceedingly difficult one, deserving quite as much attention as does the technique in proof.9

The premise of value and the standard of value represent elements of a valuation. Â They provide guidelines that can be followed to assist the analyst in the valuation. Unlike tax-related judicial precedent, where the premise and standard of value have been consistent and are defined, the premise and standard of value used in marital dissolution matters varies from state to state, and sometimes even within a state.

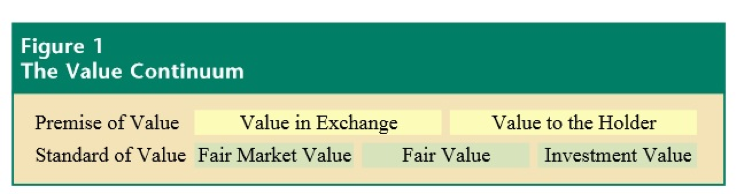

The premise and standard of value are not always written out in black and white and, in most marital dissolution cases, have to be interpreted through prior cases and state statutes. There are two different premises of value—value in exchange and value to the holder, that will help define the standard of value.

Value in exchange is the value of the business or business interest changing hands, in a real or a hypothetical sale. Â Accordingly, discounts, including those for lack of control and lack of marketability, are considered in order to estimate the value of the property in exchange. Â The fair market value standard and, to some extent, the fair value standard may be applied while also performing the analysis using the value in exchange premise of value.10

Value to the holder represents the value of a property that is not being sold, but, instead, is being maintained in its present form by its present owner. The property does not necessarily have to be marketable in order to be valuable.11

Figure 1 illustrates this value continuum.12

Valuing S Corporations in Family Law Engagements

Some states apply what they define as fair market value, while others apply a fair value or investment value definition. Â It should be noted that the selected standard of value may diverge from the original definition.

A court, as illustrated in the case in Bernier, may use the term fair market value, but use attributes of either fair value or investment value.  It is important not only to know what standard is being used, but to know how it is interpreted by the court—especially the court in which your case is tried.

The most widely used definition for fair market value was codified by the Internal Revenue Service for tax-related matters.  Tax-related courts have ruled that a hypothetical entity level tax should not be applied to an S corporation’s benefit stream.

Statutory fair value as used by the courts for shareholder dissent and oppression deals with corporate actions and is therefore determined on a state-by-state basis. Â Fair value as used herein is different from the definition of fair valued used for financial reporting. One court13 ruled that S corporations should be tax-affected at the entity level under the fair value standard, albeit not at a zero rate or at a C corporation rate.

Investment value is a widely used standard of value for marital dissolution cases and often is referred to as intrinsic value.14 Investment value provides a going concern value to the current owner, and doesn’t assume a hypothetical buyer.15

Divorce courts will often rely on other courts, along with tax and statutory case law, to mold their own distinct definition. Â As explained earlier, different courts treat tax-affecting differently for different purposes. Â Because of different viewpoints, determining how courts are going to view the treatment of S corporations may require some interpretation of precedent setting cases.

The courts and experts in Bernier used the term fair market value, but the characteristics of the term do not adhere to the generally accepted term.

The following are excerpts from the Bernier cases:

[A] buyer of either entity has to consider the tax consequences of the income generated.  A shareholder of a C corporation only personally pays taxes on the dividend that it receives.  It has actually received the dividend and can utilize those monies to pay the resultant tax. . . .  A shareholder of an S corporation pays taxes on its proportionate share of the company, whether or not it actually receives the cash.  If sufficient funds were not received by the shareholder then he would have to utilize personal funds to pay the taxes.  When the S corporation distributes additional funds to the shareholders so that the tax can be paid . . . the working capital of the company is reduced, and the income available to distribute to the owners is also reduced.  Therefore, the Court believes that a deduction for taxes that will be owed must be made to either earnings or cash flow before an appropriate valuation can be made. . . .

As a preliminary matter, where valuation of assets occurs in the context of divorce, and where one of the parties will maintain, and the other be entirely divested of, ownership of a marital asset after divorce, the judge must take particular care to treat the parties not as arm’s-length hypothetical buyers and sellers in a theoretical open market, but as fiduciaries entitled to equitable distribution of their marital assets. . . .

Further, careful financial analysis tells us that applying the C corporation rate of taxation to an S corporation severely undervalues the fair market value of the S corporation by ignoring the tax benefits of the S corporation structure and failing to compensate the seller for the loss of those benefits . . . we agree with a recent decision of the Delaware Court of Chancery that failure to tax affect an S corporation entirely artificially will inflate the value of the S corporation by overstating the rate of return that the retaining shareholder could hope to achieve.16

These passages provide insight on how the court defined fair market value, which in this case leans more towards a value to the holder premise. Â The judge in Bernier I appeared to have an understanding of how S corporations were taxed and the benefits that come with that, but at the time only had the guidance of the tax-related judicial decisions; Kessler was not tried until 2007 and will be discussed later.

The court in Bernier II stated:

Even though the judge did not have the benefit of the Kessler decision at the time she rendered her judgment, these circumstances alone should have prompted the judge to look past the all-or-nothing approach of the parties’ experts and pay particular attention to the facts of this case over more abstract considerations.17

The ruling and analysis in the Bernier cases are consistent with the value-to-the-holder premise which leans more towards an investment value standard, even though the term fair market value is repeatedly referenced.

All parties involved also agreed that no actual transaction would occur and that the husband would purchase the wife’s interest to maintain total control which supports an investment value—no hypothetical buyer.

Now that we have discussed the standard and premise of value, we have a much clearer idea of how to handle the remaining three differences in the experts’ opinion of the following:Â

- Tax-affecting S corporation benefit stream

- Key man discount

- Discount for lack of marketability

Tax-Affecting the Income Stream

Bernier I

Background

In Bernier I, the husband’s analyst tax-affected the income stream using an “average corporate rate” of 35 percent.  The analyst argued that tax-affecting an S corporation at the C corporation rate was appropriate. This is because a person contemplating the purchase of an S corporation would factor into his probable rate of return the tax consequences of the purchase.

The wife’s analyst did not tax-affect the income stream because, as he testified, an S corporation, unlike a C corporation, does not pay taxes at the entity level, and because no sale of the business was contemplated.18

The Court’s Findings

The judge rejected the wife’s valuation analyst opinion on the grounds that he improperly combined pretax and post-tax data in establishing a capitalization rate and lacked experience valuing S corporations.  The judge adopted the husband’s valuation analyst method of tax-affecting and concluded the fair market value of the S corporations was $7.85 million.

In concluding that the income stream of the S corporation should be tax-affected for valuation purposes, the judge cited Gross, an estate and gift tax case, using the fair market value standard of value and a value in exchange premise of value.

Commentary

In this case, the analysts’ alternative viewpoints could be explained by different interpretations of the standard of value.  The wife’s analyst applied the approach advised by tax-related courts using the fair market value definition, while the husband’s analyst method was more representative of a value to the holder premise.  As will be discussed later, the courts find that the application of a C corporation tax rate still understates value.

The wife’s analyst approach could be interpreted as abiding to both a fair market value (no taxes at entity level) and an investment value (no contemplated sale of the business).  An argument that is repeatedly made for not tax-affecting S corporations under the fair market value standard—for estate and gift tax purposes—pertains to the holding period of the investment.

It is assumed that the longer the holding period, the higher the perceived premium from the tax benefits will be. Â In this case, no contemplated sale of the business is expected which would result in the prolonged S corporation election.

The husband’s analyst testified that a hypothetical buyer would factor in the shareholder level taxes.  The use of a hypothetical buyer language could be interpreted as the use of fair market value, for estate and gift tax purposes.

However, tax-related precedent do not accept the implementation of a hypothetical tax.  So, in this regard, the analyst’s definition deviates from the generally accepted term.

It should also be noted that, by not tax-affecting, or by tax-affecting at a zero rate, an S corporation’s income stream will produce cash flow at the entity level, not at the shareholder level.

This is important because, as stated earlier, the court is looking for an equitable distribution, value to the holder, not a value in exchange.

Bernier II

Background/Analysis

On appeal, the Massachusetts Supreme Court noted the primary advantage of an S corporation over a C corporation is that the S corporation is not federally taxed at the corporate level. Â Rather, S corporation earnings are passed through to shareholders and taxed at the individual level. I n contrast, C corporation earnings are taxed at the corporate and personal level.

The Massachusetts Supreme Court disagreed with the citing of Gross v. Commissioner to support the decision in Bernier I, noting “it does not do the work to which the judge assigned it.”

The court found that there was no support in Gross for the adoption of the husband’s valuation and that applying an average tax rate of 35 percent would produce a significant undervaluation of the supermarkets, while not tax-affecting overstates the value of the supermarkets.  The case was remanded with orders to apply the tax-affecting procedure adopted in Kessler.

The court’s findings are consistent with the premise of value discussed earlier.

Kessler Background

Kessler involved dealings between majority and minority shareholders in a closely held S corporation pertaining to fiduciary considerations. Â Three of the eight shareholders of a radiology practice wanted the majority shareholders to buy out their shares.

Each side retained valuation analysts who developed markedly different outcomes.  The majority shareholder’s experts treated the S corporation as a C corporation, applying a 40 percent tax rate to the income stream.  The minority shareholder’s analyst did not tax-affect the benefit stream at all.

The judge found neither analyst’s estimate to be fair.  The court found that tax-affecting the S corporation at a hypothetical C corporation rate undervalued the company, and not tax-affecting the S corporation at all overvalued the company.

The court posed the question: if the S corporation at issue were a C corporation, at what hypothetical tax rate could it be taxed and still leave to shareholders the same amount in their pockets as they would have if they held shares in an S corporation?

To answer this question, the court performed the following analysis and stated:

To be consistent with Delaware law, I must tax affect [the company’s] future cash flows at a lower level that recognizes the full effect of the [minority shareholder’s] ability to receive cash dividends that are not subject to dividend taxes.19

Valuing S Corporations in Family Law Engagements

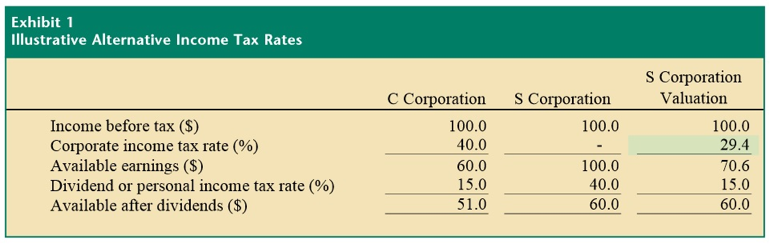

Exhibit 1 illustrates the calculation of the hypothetical tax rate used in Kessler.

The court determined that a hypothetical entity level tax rate of 29.4 percent would result in the same shareholder level earnings of an S corporation with no hypothetical entity level taxes applied.

The court’s findings are consistent with the premise of value discussed earlier. This is a good example where one state’s statutory definition of fair value is used in a different state’s statutory definition of fair market value.

Bernier I on Remand

Background/Analysis

The proceedings on remand were marked with uncertainty and disagreement as to the interpretation and implementation of the Kessler metric. Â The uncertainty in part was due to the fact that the dividend rate in 2004, the valuation date in Kessler, was 15 percent and the dividend rate as of the December 31, 2000, agreed upon valuation date for Bernier, was 40 percent.

The wife’s analyst applied the dividend tax rate that was in effect in 2000, 40 percent, which resulted in a 0 percent tax-affecting rate because the applicable personal income tax rate was also 40 percent.  The husband’s analyst applied a 5.85 percent state tax and a 39.60 percent federal tax that were in effect for 2000.

The judge found that the wife’s valuation, which utilized a zero percent tax-affecting rate, overlooked the Supreme Judicial Court’s “clear mandate” that “not tax affecting the valuation was unfair.”

The judge found that the husband’s valuation ignored the court’s decision in Bernier I that (in the probate judge’s view) any tax-affecting rate above 35 percent would undervalue the company.  The judge rejected both analysts’ new valuations and implemented the tax rate used in Kessler, 29.4 percent, to calculate the value of the supermarkets.

Bernier III

Background/Analysis

On appeal, the wife took the position that the judge, on remand, was required to follow strictly the mandate of the Supreme Judicial Court in applying the Kessler metric.

The husband argued that the tax rate to be applied by the trial court should be the federal and state tax rates that were in effect in 2000. Â The Appeals Court of Massachusetts rejected the procedure taken by the judge on remand and by the husband on remand and on the appeal.

The Appeals Court of Massachusetts found that the wife’s valuation was consistent with the Supreme Judicial Court’s mandate and remanded the case.

The court distinguished between a zero percent tax-affecting rate and not tax-affecting at all due to the specific details of the tax rates at the time of valuation. Â The court noted:

There is a distinction to be drawn between failing to tax affect at all the earnings of the supermarkets because an S corporation does not pay federal taxes at the entity level . . . and utilizing a zero percent tax affecting rate arrived at through application of all applicable rates.

If the Kessler metric is to be implemented, the tax rates should reflect the “as of date” of the valuation.  It should also be noted that a different tax rate could be implemented depending on the pool of potential buyers.

The court in both Kessler and Bernier II commented that “a different analysis might apply if the profits of the S corporation were plowed back into the company instead of distributed, or if the shareholders were not individually taxed at the highest bracket.”20

As can be seen in Exhibit 1, changes in the tax rates will change the hypothetical entity level tax rate applied to S corporations. Â Holding all else equal:

- A decrease in the personal income rate will decrease the hypothetical entity tax rate, while an increase in the personal tax rate will increase the hypothetical entity tax rate.

- A decrease in the dividend rate will increase the hypothetical entity tax rate, while an increase in the dividend rate will decrease the hypothetical entity tax rate.

- If the dividend rate exceeds the personal income rate, a negative corporate tax will be applied, resulting in a discount rather than a premium.

- As the dividend and personal tax rates converge, the hypothetical S corporation tax diminishes until the tax rates equal each other and a zero tax rate is applied; this is what happened in Bernier.

- As the dividend and personal tax rates diverge, dividend tax decreases and personal tax rate increases, the hypothetical S corporation tax increases.

- The implied S corporation premium increases as the dividend rate increases; C corporation earnings are taxed at a higher rate and S corporation earnings not affected by the dividend rate.

Key Person Discount for Lack of Marketability

In Bernier I,  all parties agreed that the husband’s expertise was critical to the continued success of the supermarkets.  Because of this, the husband’s analyst applied a 10 percent key person21 discount, assuming that after the divorce, the supermarkets could be sold to a third party who would replace the husband.

The wife’s analyst maintained that, because there was no contemplated sale of the company, no key person discount should be applied.  The judge in Bernier I adopted the key man discount applied by the husband’s expert.

On appeal, the court ruled that, given the circumstances, this was an error.  The appeals court cited the husband’s testimony that he would maintain total control of the supermarkets after the divorce and rejected the key person discount.

In Bernier I, the husband’s analyst applied a 10 percent discount for lack of marketability.  The wife’s expert maintained that, because there was no contemplated sale of the company, no discount for lack of marketability should be applied.

The judge in Bernier I adopted the discount for lack of marketability applied by the husband’s analyst.  On appeal, the court ruled that, given the circumstances, this was an error.

The appeals court again cited the husband’s testimony that he would maintain total control of the supermarkets after the divorce and rejected the discount for lack of marketability stating:

Applying a marketability discount in light of the husband’s intended, and presumed, acquisition of the supermarkets unfairly deflated their value.22

Circling back to the standard of value discussion, we can see how the application of a key person discount and a discount for lack of marketability would contradict the value to the holder premise. The appeals court decision to reject the key person discount and discount for lack of marketability is consistent with the value to the holder premise.

Conclusion

It is the responsibility of the valuation analyst to provide a sound analysis that follows generally accepted business valuation standards. Â Analysts should also be aware of the viewpoints of the courts. Â Sometimes, these can be contradicting. Â In the end, the courts will always have the last word. Â The less the courts have to interpret or assume, the clearer the picture will be.

At a recent seminar, a judge said that courts don’t want to make hard decisions pertaining to valuation, but if they are forced to, they will.

State statues and the courts define the standard of value for marital dissolution engagements. I t is the valuation profession’s job to interpret and adhere to these standards. It is best to leave as little as possible open to interpretation.  This can be accomplished through studying how different courts define different standards of value.

It is important for legal counsel and the valuation analyst to agree on the standard of value and the definition of the selected standard—this is especially true with statutory engagements.  When determining an appropriate standard of value, certain words can imply different premises of value.

Language containing “hypothetical,”  “willing buyer,”  “willing seller,” and “arm’s-length” can imply a value in exchange premise.  Language containing “knowing buyer,” “unwilling seller,”  “pro rata,” and “equitable distribution” can imply a value to the holder premise.

It is also important to understand how courts assign value to personal goodwill. Â The inclusion of personal goodwill can imply a value to the holder premise, while the exclusion of personal goodwill can imply a value in exchange.

Once a standard of value is selected, along with the underlying premise of value, it will be easier to understand how the courts view the tax-affecting of S corporations. Â With the increase in personal and dividend income tax rates (the Medicare Surtax will also apply to dividends, for wealthier Americans), the premise of value will be important in order to identify the correct tax rates.

As mentioned earlier, the court in both Kessler and Bernier II commented that “a different analysis might apply if the . . . shareholders were not individually taxed at the highest bracket.”23

In the end, a thorough understanding of the topic and sound logic should prevail.

View Article PDF

Notes

1.     This includes Bernier v. Bernier, Dukes Division of the Probate and Family Court Department (July 28, 2003); Judith E. Bernier v. Stephen A. Bernier, 873 N.E.2d 216 (Mass. 2007); and Judith E. Bernier v. Stephen A. Bernier, 970 N.E. 2d 363 (Mass. App. Ct. 2012).

2.     “The History and Challenges of America’s Dominant Business Structure,” S Corporation Association of America, accessed January 20, 2013, http://www.s-corp.org/our-history/

3.      Statistics of Income – 2009 Corporate Income Tax Returns (Washington, DC: Internal Revenue Service, 2011).

4.     Walter L. Gross v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 1999-254, aff’d 272 F.3d 333 (6th Cir. 2001).

5.     Bernier v. Bernier, Dukes Division of the Probate and Family Court Department (July 28, 2003).

6.     Judith E. Bernier v. Stephen A. Bernier, 873 N.E.2d 216 (Mass. 2007).

7.     Delaware Open MRI Radiology Associates, P.A. v. Howard B. Kessler, 898 A.2d 290, (Del. Ch. 2006).

8.     Judith E. Bernier v. Stephen A. Bernier, 970 N.E.2d 363 (Mass. App. Ct. 2012).

9.     Jay E. Fishman, Shannon P. Pratt, and William J. Morrison. Standards of Value: Theory and Application. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2007), 21.

10.   Ibid., 20.

11.   Ibid., 21.

12.   Ibid., 244.

13.   See Delaware Open MRI Radiology Associates, P.A. v. Howard B. Kessler, 898 A.2d 290, (Del. Ch. 2006).

14.   Fishman, Pratt, Morrison. Standards of Value: Theory and Application, 181.

15.   Ibid.

16.   Judith E. Bernier v. Stephen A. Bernier, 873 N.E.2d 216 (Mass. 2007).

17.   Ibid.

18.   All parties stipulated that the husband would receive all of the shares and intended to operate the corporations as S corporations.

19.   Delaware Open MRI Radiology Associates v. Howard B. Kessler, 898 A.2d 290, (Del. Ch. 2006).

20.   Judith E. Bernier v. Stephen A. Bernier, 873 N.E.2d 216 (Mass. 2007).

21.   This also included broker’s fees and advertising costs associated with marketing the supermarkets.

22.   Judith E. Bernier v. Stephen A. Bernier, 873 N.E.2d 216 (Mass. 2007).

23.   Ibid.

This article first appeared in Willamette Management Associates publication, Insights—Spring, 2013 issue.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://m.c.lnkd.licdn.com/mpr/mpr/shrink_200_200/p/1/005/011/00e/15c67f6.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Zach Oehlman is an associate in the Chicago practice office of Willamette Management Associates.  Zach can be reached at (773) 399-4322 or at zoehlman@willamette.com. More information may be found at www.willamette.com.[/author_info] [/author]